Loom

A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but the basic function is the same.

Etymology and usage

The word "loom" derives from the Old English geloma, formed from ge- (perfective prefix) and loma, a root of unknown origin; the whole word geloma meant a utensil, tool, or machine of any kind. In 1404 "lome" was used to mean a machine to enable weaving thread into cloth.[1][2][failed verification] By 1838 "loom" had gained the additional meaning of a machine for interlacing thread.[citation needed]

Components and actions

Basic structure

Weaving is done on two sets of threads or yarns, which cross one another. The warp threads are the ones stretched on the loom (from the Proto-Indo-European *werp, "to bend"[3]). Each thread of the weft (i.e. "that which is woven") is inserted so that it passes over and under the warp threads.

The ends of the warp threads are usually fastened to beams. One end is fastened to one beam, the other end to a second beam, so that the warp threads all lie parallel and are all the same length. The beams are held apart to keep the warp threads taut.

The textile is woven starting at one end of the warp threads, and progressing towards the other end. The beam on the finished-fabric end is called the cloth beam. The other beam is called the warp beam.

Beams may be used as rollers to allow the weaver to weave a piece of cloth longer than the loom. As the cloth is woven, the warp threads are gradually unrolled from the warp beam, and the woven portion of the cloth is rolled up onto the cloth beam (which is also called the takeup roll). The portion of the fabric that has already been formed but not yet rolled up on the takeup roll is called the fell.

Not all looms have two beams. For instance, warp-weighted looms have only one beam; the warp yarns hang from this beam. The bottom ends of the warp yarns are tied to dangling loom weights.

- Weaving demonstration on an 1830 handloom in the weaving museum in Leiden

Motions

A loom has to perform three principal motions: shedding, picking, and battening.

- Shedding. Shedding is pulling part of the warp threads aside to form a shed (the space between the raised and unraised warp yarns). The shed is the space through which the filling yarn, carried by the shuttle, can be inserted, forming the weft.

- Sheds may be simple: for instance, lifting all the odd threads and all the even threads alternately produces a tabby weave (the two sheds are called the shed and countershed). More intricate shedding sequences can produce more complex weaves, such as twill.

- Picking. A single crossing of the weft thread from one side of the loom to the other, through the shed, is known as a pick. Picking is passing the weft through the shed. A new shed is then formed before a new pick is inserted.

- Conventional shuttle looms can operate at speeds of about 150 to 160 picks per minute.[4]

- Battening. After the pick, the new pass of weft thread has to be tamped up against the fell, to avoid making a fabric with large, irregular gaps between the weft threads. This compression of the weft threads is called battening.

There are also usually two secondary motions, because the newly constructed fabric must be wound onto cloth beam. This process is called taking up. At the same time, the warp yarns must be let off or released from the warp beam, unwinding from it. To become fully automatic, a loom needs a tertiary motion, the filling stop motion. This will brake the loom if the weft thread breaks.[4] An automatic loom requires 0.125 hp to 0.5 hp to operate (100W to 400W).

Components

A loom, then, usually needs two beams, and some way to hold them apart. It generally has additional components to make shedding, picking, and battening faster and easier. There are also often components to help take up the fell.

The nature of the loom frame and the shedding, picking, and battening devices vary. Looms come in a wide variety of types, many of them specialized for specific types of weaving. They are also specialized for the lifestyle of the weaver. For instance, nomadic weavers tend to use lighter, more portable looms, while weavers living in cramped city dwellings are more likely to use a tall upright loom, or a loom that folds into a narrow space when not in use.

Shedding methods

It is possible to weave by manually threading the weft over and under the warp threads, but this is slow. Some tapestry techniques use manual shedding. Pin looms and peg looms also generally have no shedding devices. Pile carpets generally do not use shedding for the pile, because each pile thread is individually knotted onto the warps, but there may be shedding for the weft holding the carpet together.

Usually weaving uses shedding devices. These devices pull some of the warp threads to each side, so that a shed is formed between them, and the weft is passed through the shed. There are a variety of methods for forming the shed. At least two sheds must be formed, the shed and the countershed. Two sheds is enough for tabby weave; more complex weaves, such as twill weaves, satin weaves, diaper weaves, and figured (picture-forming) weaves, require more sheds.

Heddle-bar and shed-rod

Heddle-rods and shedding-sticks are not the fastest way to weave, but they are very simple to make, needing only sticks and yarn. They are often used on vertical[5] and backstrap looms.[6] They allow the creation of elaborate supplementary-weft brocades.[6] They are also used on modern tapestry looms; the frequent changing of weft colour in tapestry makes weaving tapestry slow, so using faster, more complex shedding systems isn't worthwhile. The same is true of looms for handmade knotted-pile carpet; hand-knotting each pile thread to the warp takes far more time than weaving a couple of weft threads to hold the pile in place.

At its simplest, a heddle-bar is simply a stick placed across the warp and tied to individual warp threads. It is not tied to all of the warp threads; for a plain tabby weave, it is tied to every other thread. The little loops of string used to tie the wraps to the heddle bar are called heddles or leashes. When the heddle-bar is pulled perpendicular to the warp, it pulls the warp threads it is tied to out of position, creating a shed.

| Elements of a warp-weighted loom |

|

| A warp-weighted loom with a single heddle bar. See body text for labels. |

A warp-weighted loom (see diagram) typically uses a heddle-bar, or several. It has two upright posts (C); they support a horizontal beam (D), which is cylindrical so that the finished cloth can be rolled around it, allowing the loom to be used to weave a piece of cloth taller than the loom, and preserving an ergonomic working height. The warp threads (F, and A and B) hang from the beam and rest against the shed rod (E). The heddle-bar (G) is tied to some of the warp threads (A, but not B), using loops of string called leashes (H). So when the heddle rod is pulled out and placed in the forked sticks protruding from the posts (not lettered, no technical term given in citation), the shed (1) is replaced by the counter-shed (2). By passing the weft through the shed and the counter-shed, alternately, cloth is woven.[7]

Several heddle-bars can be used side-by-side; three or more can be used to weave twill weaves, for instance.

There are also other ways to create counter-sheds. A shed-rod is simpler and easier to set up than a heddle-bar, and can make a counter-shed. A shed-rod (shedding stick, shed roll) is simply a stick woven through the warp threads. When pulled perpendicular to the threads (or rotated to stand on edge, for wide, flat shedding rods), it creates a counter shed. The combination of a heddle-bar and a shedding-stick can create the shed and countershed needed for a plain tabby weave, as in the video.

There are also slitted heddle-rods, which are sawn partway through, with evenly-placed slits. Each warp thread goes in a slit. The odd-numbered slits are at 90 degrees to the even slits. The rod is rotated back and forth to create the shed and countershed,[8] so it is often large-diameter.[9]

Tablet weaving

Tablet weaving uses cards punched with holes. The warp threads pass through the holes, and the cards are twisted and shifted to created varied sheds. This shedding technique is used for narrow work. It is also used to finish edges, weaving decorative selvage bands instead of hemming.

Rotating-hook heddles

There are heddles made of flip-flopping rotating hooks, which raise and lower the warp, creating sheds. The hooks, when vertical, have the weft threads looped around them horizontally. If the hooks are flopped over on side or another, the loop of weft twists, raising one or the other side of the loop, which creates the shed and countershed.[10]

Rigid heddles

Rigid heddles are generally used on single-shaft looms. Odd warp threads go through the slots, and even ones through the circular holes, or vice-versa. The shed is formed by lifting the heddle, and the countershed by depressing it. The warp threads in the slots stay where they are, and the ones in the circular holes are pulled back and forth. A single rigid heddle can hold all the warp threads, though sometimes multiple rigid heddles are used.

Treadles may be used to drive the rigid heddle up and down.

Non-rigid heddles

- String healds, with a small eyelet called a mail in the middle of the red section, and larger lops on either side

- Very similar healds, with the wooden staves threaded through them top and bottom, and the warp threads in the process of being drawn in (that is, threaded through the eyes of the healds)

- How healds can thread onto staves and the warp threads (Swedish caption shows eye, and warp thread)

- Wire healds on wire staves. A few extra healds have not had warp threads drawn in through them.

- A variety of metal healds, made from wire and straps

Rigid heddles or (above) are called "rigid" to distinguish them from string and wire heddles. Rigid heddles are one-piece, by non-rigid ones are multi-piece. Each warp thread has its own heald (also, confusingly, called a heddle). The heald has an eyelet at each end (for the staves, also called shafts) and one in the middle, called the mail, (for the warp thread). A row of these healds is slid onto two staves, the upper and lower staves; the staves together, or the staves together with the healds, may be called a heald frame, which is, confusingly, also called a shaft and a harness.[11] Replacable, interchangable healds can be smaller, allowing finer weaves.

Unlike a rigid heddle, a flexible heddle cannot push the warp thread. This means that two heald frames are needed even for a plain tabby weave. Twill weaves require three or more heald frames (depending on the type of twill), and more complex figured weaves require still more frames.

The different heald frames must be controlled by some mechanism, and the mechanism must be able to pull them in both directions. They are mostly controlled by treadles; creating the shed with the feet leaves the hands free to ply the shuttle. However in some tabletop looms, heald frames are also controlled by levers.[12][better source needed]

Treadle-controlled looms

In treadle looms, the weaver controls the shedding with their feet, by treading on treadles. Different treadles and combinations of treadles produce different sheds. The weaver must remember the sequence of treadling needed to produce the pattern.

The precise mechanism by which the treadles control the heddles varies. Rigid-heddle treadle looms do exist, but the heddles are usually flexible. Sometimes, the treadles are tied directly to the staves (with a Y-shaped bridle so they stay level). Alternately, they may be tied to a stick called a lamm, which in turn is tied to the stave, to make the motion more controlled and regular. The lamm may pivot or slide.

Counterbalance looms are the most common type of treadle loom globally, as they are simple and give a smooth, quiet, quick motion.[13] The heald frames are joined together in pairs, by a cord running over heddle pulleys or a heddle roller. When one heald frame rises, the other falls. It takes a pair of treadles to control a pair of frames. Counterbalance looms are usually used with two or four frames, though some have as many as ten.[13]

In theory each pair of heald frames has to have an equal number to warps pulled by each frame, so the patterns that can be made on them are limited.[14] In practice, fairly unbalanced tie-ups just make the shed a bit smaller, and as the shed on a counterbalance loom is adjustable in size and quite large to start with (compared to other types of loom), so it is entirely possible to weave good cloth on a counterbalance loom with unbalanced heald frames,[15][13] unless the loom is extremely shallow (that is, the length of warp being pulled on is short, less than 1 meter or 3 feet), which exacerbates the slightly uneven tension.[13] Limited patterns are not, of course, a disadvantage when weaving plainer patterns, such as tabbies and twills.

Jack looms (also called single-tieup-looms and rising-shed looms[16]), have their treadles connected to jacks, levers that push or pull the heald frames up; the harnesses are weighted to fall back into place by gravity. Several frames can be connected to a single treadle. Frames can also be raised by more than one treadle. This allows treadles to control arbitrary combinations of frames, which vastly increases the number of different sheds that can be created from the same number of frames. Any number of treadles can also be engaged at once, meaning that the number of different sheds that can be selected is two to the power of the number of treadles. Eight is a large but reasonable number of treadles, giving a maximum of 28=256 sheds (some of which will probably not have enough threads on one side to be useful).[citation needed] Having more possible sheds allows more complex patterns,[14][16] such as diaper weaves.[17]

Jack looms are easy to make and to tie up (if not quite as easy as counterbalance looms). The gravity return makes jack looms heavy to operate. The shed of a jack loom is smaller for a given length of warp being pulled aside by the heddles (loom depth). The warp threads being pulled up by the jacks are also tauter than the other warp threads (unlike a counter balance loom, where the threads are pulled an equal amount in opposite directions). Uneven tension makes weaving evenly harder. It also lowers the maximum tension at which one can practically weave.[14][16] If the threads are rough, closely-spaced, very long or numerous, it can be hard to open the sheds on the jack loom.[16] Jack looms without castles (the superstructure above the weft) have to lift the heald frames from below, and are noiser due to the impact of wood on wood; elastomer pads can reduce the noise.[13]

In countermarch looms, the treadles are tied to lamms,[18][14] which may pivot at one end or slide up and down.[19] Half of the lamms in turn connect to jacks, which also pivot, and push or pull the staves up or down.[18] Some countermarches have two horizontal jacks per shaft, others a single vertical jack.[13] Each treadle is tied to all of the heald frames, moving some of them up and the rest of them down.[13] This allows the complex combinatorial treadles of a jack loom, with the large shed and balanced, even tension of a counterbalance loom, with its quiet, light operation. Unfortunately, countermarch looms are more complex, harder to build, slower to tie up,[18][14][13] and more prone to malfunction.[18][20]

Figure harness and the drawloom

A drawloom is for weaving figured cloth. In a drawloom, a "figure harness" is used to control each warp thread separately,[21] allowing very complex patterns. A drawloom requires two operators, the weaver, and an assistant called a "drawboy" to manage the figure harness.

The earliest confirmed drawloom fabrics come from the State of Chu and date c. 400 BC.[22] Some scholars speculate an independent invention in ancient Syria, since drawloom fabrics found in Dura-Europas are thought to date before 256 AD.[22][23] The draw loom was invented in China during the Han dynasty (State of Liu?);[contradictory][24] foot-powered multi-harness looms and jacquard looms were used for silk weaving and embroidery, both of which were cottage industries with imperial workshops.[25] The drawloom enhanced and sped up the production of silk and played a significant role in Chinese silk weaving. The loom was introduced to Persia, India, and Europe.[24]

Dobby head

A dobby head is a device that replaces the drawboy, the weaver's helper who used to control the warp threads by pulling on draw threads. "Dobby" is a corruption of "draw boy". Mechanical dobbies pull on the draw threads using pegs in bars to lift a set of levers. The placement of the pegs determines which levers are lifted. The sequence of bars (they are strung together) effectively remembers the sequence for the weaver. Computer-controlled dobbies use solenoids instead of pegs.

Jacquard head

The Jacquard loom is a mechanical loom, invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801, which simplifies the process of manufacturing figured textiles with complex patterns such as brocade, damask, and matelasse.[26][27] The loom is controlled by punched cards with punched holes, each row of which corresponds to one row of the design. Multiple rows of holes are punched on each card and the many cards that compose the design of the textile are strung together in order. It is based on earlier inventions by the Frenchmen Basile Bouchon (1725), Jean Baptiste Falcon (1728), and Jacques Vaucanson (1740).[28] To call it a loom is a misnomer. A Jacquard head could be attached to a power loom or a handloom, the head controlling which warp thread was raised during shedding. Multiple shuttles could be used to control the colour of the weft during picking. The Jacquard loom is the predecessor to the computer punched card readers of the 19th and 20th centuries.[29]

- The punched-card control mechanism of a Jacquard loom in use in 2009, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India.

- Battening on a Jacquard loom in Łódź.

- A female worker changing jacquard cards in a lace machine in a Nottingham factory (1918).

- Boy next to two weaving looms with the weaving pattern on reams of paper (India).

- Following the pattern, holes are punched in the appropriate places on a Jacquard card.

- Manual loom with double width and Jacquard loom, Colegio del Arte Mayor de la Seda of Valencia.

- The Jacquard cards control the heads on a loom.

Picking (weft insertion)

The weft may be passed across the shed as a ball of yarn, but usually this is too bulky and unergonomic. Shuttles are designed to be slim, so they pass through the shed; to carry a lot of yarn, so the weaver does not need to refill them too often; and to be an ergonomic size and shape for the particular weaver, loom, and yarn. They may also be designed for low friction.

Stick shuttles

Unnotched stick shuttles

At their simplest, these are just sticks wrapped with yarn. They may be specially shaped, as with the bobbins and bones used in tapestry-making (bobbins are used on vertical warps, and bones on horizontal ones).[30][31]

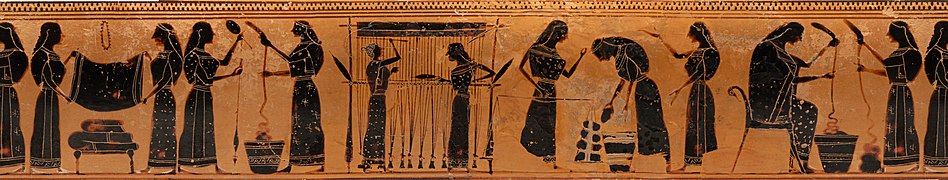

- Shuttles are passed, not thrown, through warp-weighted looms. These Ancient Greek weavers have a yarn-wrapped stick.[7]

- Tapestry bobbins are used on vertical-warp looms.

- Tapestry bobbins, empty and full

- Tapestry bones are used on horizontal-warp looms

- Tapestry bones actually made from cannonbones (those in the last image are wooden)

- Paper quills (paper bobbins) used as tapestry bones in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Notched stick shuttles, rag shuttles, and ski shuttles

- Stick shuttles must be passed, not thrown, which is inconvenient for wide warps.

- Belt or band shuttle, a short shuttle used for inkle weaving. This extra-sturdy shuttle is also used at a batten, to beat the newly woven weft against the previously woven fell.[32]

- Ski shuttle.[34]

- A rag shuttle has two skis; it is used for weaving strips of rag into carpets, whence the name.[33]

- Stick shuttles wound in a figure-of-eight.

Boat shuttles

Boat shuttles may be closed (central hollow with a solid bottom) or open (central hole goes right through). The yarn may be side-feed or end-feed.[35][36] They are commonly made for 10-cm (4-inch) and 15-cm (6-inch) bobbin lengths.[37]

- Top, an open boat shuttle (the other two are closed). Bottom, a Swedish-style asymmetrical shuttle with a paper quill. All are side-feed; the topmost one runs on rollers

- Boat shuttle inside the shed. It floats on the lower warp threads. This only works on horizontal looms. Rhode Island, USA.

- Boats with square-ended recesses are intended for bobbins with end flanges. Other shuttles have round-cornered recesses. They are often intended for use with paper quills (tubes of rolled paper).

- Macedonian open shuttles with paper quills.

- A collection of open and closed shuttles in Ukraine, some clearly handmade.

- This Transylvanian shuttle was a Valentine's Day gift.

- These Assamese shuttles, presumably for very fine silk, are slender and do not hold much volume.

- Asymmetric open boat shuttle, Khotan.

- Two end-feed pirns and a side-feed bobbin (bottom)

- Simple closed, side-feed boat shuttle with a paper bobbin, Mexico

- How the conical pirn loads on an end-feed shuttle.

- Using two shuttles for weft stripes, Estonia

- Weaving with three shuttles

Flying shuttle

- Handloom with a flying shuttle. The shuttle runs in a shuttle race attached to the front of the beater bar. Subtitles describe step-by-step.

- An early fully-automated loom. The arms at the sides can be seen swinging to bash the flying shuttle back and forth.

- The automated shuttle moves almost too fast to see

- Manufacture of a cornelwood flying shuttle

- In the shuttle race.

- Narrow tanmono loom with a shuttle race. Late 18-hundreds Japan.

Hand weavers who threw a shuttle could only weave a cloth as wide as their armspan. If cloth needed to be wider, two people would do the task (often this would be an adult with a child). John Kay (1704–1779) patented the flying shuttle in 1733. The weaver held a picking stick that was attached by cords to a device at both ends of the shed. With a flick of the wrist, one cord was pulled and the shuttle was propelled through the shed to the other end with considerable force, speed and efficiency. A flick in the opposite direction and the shuttle was propelled back. A single weaver had control of this motion but the flying shuttle could weave much wider fabric than an arm's length at much greater speeds than had been achieved with the hand thrown shuttle.

The flying shuttle was one of the key developments in weaving that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. The whole picking motion no longer relied on manual skill and it was just a matter of time before it could be powered by something other than a human.

Weft insertion in power looms

Different types of power looms are most often defined by the way that the weft, or pick, is inserted into the warp. Many advances in weft insertion have been made in order to make manufactured cloth more cost effective. Weft insertion rate is a limiting factor in production speed. As of 2010, industrial looms can weave at 2,000 weft insertions per minute.[38]

There are five main types of weft insertion and they are as follows:

- Shuttle: The first-ever powered looms were shuttle-type looms. Spools of weft are unravelled as the shuttle travels across the shed. This is very similar to projectile methods of weaving, except that the weft spool is stored on the shuttle. These looms are considered obsolete in modern industrial fabric manufacturing because they can only reach a maximum of 300 picks per minute.

- Air jet: An air-jet loom uses short quick bursts of compressed air to propel the weft through the shed in order to complete the weave. Air jets are the fastest traditional method of weaving in modern manufacturing and they are able to achieve up to 1,500 picks per minute. However, the amounts of compressed air required to run these looms, as well as the complexity in the way the air jets are positioned, make them more costly than other looms.

- Water jet: Water-jet looms use the same principle as air-jet looms, but they take advantage of pressurized water to propel the weft. The advantage of this type of weaving is that water power is cheaper where water is directly available on site. Picks per minute can reach as high as 1,000.

- Rapier loom: This type of weaving is very versatile, in that rapier looms can weave using a large variety of threads. There are several types of rapiers, but they all use a hook system attached to a rod or metal band to pass the pick across the shed. These machines regularly reach 700 picks per minute in normal production.

- Projectile: Projectile looms utilize an object that is propelled across the shed, usually by spring power, and is guided across the width of the cloth by a series of reeds. The projectile is then removed from the weft fibre and it is returned to the opposite side of the machine so it can be reused. Multiple projectiles are in use in order to increase the pick speed. Maximum speeds on these machines can be as high as 1,050 ppm.

- Circular: Modern circular looms use up to ten shuttles, driven in a circular motion from below by electromagnets, for the weft yarns, and cams to control the warp threads. The warps rise and fall with each shuttle passage, unlike the common practice of lifting all of them at once. Circular looms are used to create seamless tubes of fabric for products such as hosiery, sacks, clothing, fabric hoses (such as fire hoses) and the like.[39]

Battening

- Coast Salish sword beater, North American west coast

- Sword beaters (or battens) on upright looms are indeed swung like a sword

- Sword beater on an Ancient Egyptian horizontal ground-pegged loom, being held by two people

- Weaving comb used for battening, Braga, Portugal

- Reed beater mounted in a beater bar

- Rigid heddles are a shedding device that can also act as a reed.

The newest weft thread must be beaten against the fell. Battening can be done with a long stick placed in the shed parallel to the weft (a sword batten), a shorter stick threaded between the warp threads perpendicular to warp and weft (a pin batten), a comb, or a reed (a comb with both ends closed, so that it has to be sleyed, that is have the warp threads threaded through it, when the loom is warped). For rigid-heddle looms, the heddle may be used as a reed.

Secondary motions

Dandy mechanism

Patented in 1802, dandy looms automatically rolled up the finished cloth, keeping the fell always the same length. They significantly speeded up hand weaving (still a major part of the textile industry in the 1800s). Similar mechanisms were used in power looms.

Temples

The temples act to keep the cloth from shrinking sideways as it is woven. Some warp-weighted looms had temples made of loom weights, suspended by strings so that they pulled the cloth breadthwise.[7] Other looms may have temples tied to the frame, or temples that are hooks with an adjustable shaft between them. Power looms may use temple cylinders. Pins can leave a series of holes in the selvages (these may be from stenter pins used in post-processing).

Frames

Loom frames can be roughly divided, by the orientation of the warp threads, into horizontal looms and vertical looms. There are many finer divisions. Most handloom frame designs can be constructed fairly simply.[40]

Backstrap loom

The back-strap loom (also known as belt loom)[41] is a simple loom with ancient roots, still used in many cultures around the world (such as Andean textiles, and in Central, East and South Asia).[42] It consists of two sticks or bars between which the warps are stretched. One bar is attached to a fixed object and the other to the weaver, usually by means of a strap around the weaver's back.[43] The weaver leans back and uses their body weight to tension the loom.

Both simple and complex textiles can be woven on backstrap looms. They produce narrowcloth: width is limited to the weaver's armspan. They can readily produce warp-faced textiles, often decorated with intricate pick-up patterns woven in complementary and supplementary warp techniques, and brocading. Balanced weaves are also possible on the backstrap loom.

- A loom made of sticks and string. The top endbar is tied to a fixed object using green rope; the lower end bar is attached to a leather strap around the weaver's back. Between, two heddle rods and several shedding rods. The sticks to one side are probably sword beaters. No shuttles or bobbins are being used.

- T'boli dream weavers using two-bar bamboo backstrap looms (legogong) to weave t'nalak cloth from abacá fiber. One bar is attached to the ceiling of the traditional T'boli longhouse, while the other is attached to the lower back. The cloth is being patterned by dying the warp, so the loom equipment is simple; a heddle rod, a shedding stick, and a batten. She is also using a footrest. Philippines.[44][45]

- This Hlai weaver tensions her traditional backstrap loom with her feet. She is using a large number of slim heddle rods, attached to only a few warp threads; these are sometimes called pattern rods. Hainan Island, Southern People's Republic of China.

- A Sámi weaver doing inkle weaving on a backstrap loom with a rigid heddle. She seems to be using a hollow half-bone as a beater and as a race for a bobbin. Norway, 1956.

- An Icelandic backstrap loom, 1903. The inkle workpiece is so narrow that no beams are needed; the warp ends are simply tied as one. Tablets are used for the shedding.

Warp-weighted loom

The warp-weighted loom is a vertical loom that may have originated in the Neolithic period. Its defining characteristic is hanging weights (loom weights) which keep bundles of the warp threads taut. Frequently, extra warp thread is wound around the weights. When a weaver has woven far enough down, the completed section (fell) can be rolled around the top beam, and additional lengths of warp threads can be unwound from the weights to continue. This frees the weaver from vertical size constraint. Horizontally, breadth is limited by armspan; making broadwoven cloth requires two weavers, standing side by side at the loom.

Simple weaves, and complex weaves that need more than two different sheds, can both be woven on a warp-weighted loom. They can also be used to produce tapestries.

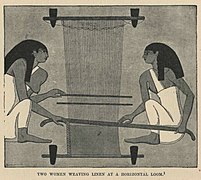

Pegged or floor loom

In pegged looms, the beams can be simply held apart by hooking them behind pegs driven into the ground, with wedges or lashings used to adjust the tension. Pegged looms may, however, also have horizontal sidepieces holding the beams apart.

Such looms are easy to set up and dismantle, and are easy to transport, so they are popular with nomadic weavers. They are generally only used for comparatively small woven articles.[46] Urbanites are unlikely to use horizontal floor looms as they take up a lot of floor space, and full-time professional weavers are unlikely to use them as they are unergonomic. Their cheapness and portability is less valuable to urban professional weavers.[47]

- A pegged loom from the Ancient Egyptian Middle Kingdom showing the use of heddle jacks. 1922 model.

- Qashqai nomad sisters, weaving a carpet on a floor loom. Near Firuzabad, Iran

Treadle loom

In a treadle loom, the shedding is controlled by the feet, which tread on the treadles.

The earliest evidence of a horizontal loom is found on a pottery dish in ancient Egypt, dated to 4400 BC. It was a frame loom, equipped with treadles to lift the warp threads, leaving the weaver's hands free to pass and beat the weft thread.[48]

A pit loom has a pit for the treadles, reducing the stress transmitted through the much shorter frame.[49]

In a wooden vertical-shaft loom, the heddles are fixed in place in the shaft. The warp threads pass alternately through a heddle, and through a space between the heddles (the shed), so that raising the shaft raises half the threads (those passing through the heddles), and lowering the shaft lowers the same threads — the threads passing through the spaces between the heddles remain in place.

A treadle loom for figured weaving may have a large number of harnesses or a control head. It can, for instance, have a Jacquard machine attached to it[50] .

- Traditional treadle loom at Ranipauwa Muktinath, Nepal (another image)

- Japanese treadle loom, late 1820s-early 1830s

- Weaving at a pit loom; the frame is built shorter, but set over a pit, so that the treadles are below ground level. Herat, Afghanistan.

- A simple tripod frame supports, not a heddle pulley, but a horse (a sort of teeter-totter); from each heddle frame hangs a treadle, trod alternately to form shed and countershed. West African loom, early 20th century

Tapestry looms

Tapestry can have extremely complex wefts, as different strands of wefts of different colours are used to form the pattern. Speed is lower, and shedding and picking devices may be simpler. Looms used for weaving traditional tapestry are called not as "vertical-warp" and "horizontal-warp", but as "high-warp" or "low-warp" (the French terms haute-lisse and basse-lisse are also used in English).[51]

- Haut-lisse tapestry loom, 2022, New Zealand

- Commercial haut-lisse tapestry loom, 2004

- A commercial basse-lisse tapestry loom in the same factory, 2004

- A power loom in the TextielMuseum Tilburg weaving a tapestry for the Niewe Kerk Middelburg; note that the threads do not vary in colour along their length.

Ribbon, Band, and Inkle weaving

Inkle looms are narrow looms used for narrow work. They are used to make narrow warp-faced strips such as ribbons, bands, or tape. They are often quite small; some are used on a tabletop. others are backstraps looms with a rigid heddle, and very portable.

Darning looms

There exist very small hand-held looms known as darning looms. They are made to fit under the fabric being mended, and are often held in place by an elastic band on one side of the cloth and a groove around the loom's darning-egg portion on the other. They may have heddles made of flip-flopping rotating hooks .[52] Other devices sold as darning looms are just a darning egg and a separate comb-like piece with teeth to hook the warp over; these are used for repairing knitted garments and are like a linear knitting spool.[53] Darning looms were sold during World War Two clothing rationing in the United Kingdom[54] and Canada,[55] and some are homemade.[56][57]

Circular handlooms

Circular looms are used to create seamless tubes of fabric for products such as hosiery, sacks, clothing, fabric hoses (such as fire hoses) and the like. Tablet weaving can be used to knit tubes, including tubes that split and join.

Small jigs also used for circular knitting are also sometimes called circular looms,[58] but they are used for knitting, not weaving.

Handlooms to power looms

A power loom is a loom powered by a source of energy other than the weaver's muscles. When power looms were developed, other looms came to be referred to as handlooms. Most cloth is now woven on power looms, but some is still woven on handlooms.[49]

The development of power looms was gradual. The capabilities of power looms gradually expanded, but handlooms remained the most cost-effective way to make some types of textiles for most of the 1800s. Many improvements in loom mechanisms were first applied to hand looms (like the dandy loom), and only later integrated into power looms.

Edmund Cartwright built and patented a power loom in 1785, and it was this that was adopted by the nascent cotton industry in England. The silk loom made by Jacques Vaucanson in 1745 operated on the same principles but was not developed further. The invention of the flying shuttle by John Kay allowed a hand weaver to weave broadwoven cloth without an assistant, and was also critical to the development of a commercially successful power loom.[59] Cartwright's loom was impractical but the ideas behind it were developed by numerous inventors in the Manchester area of England. By 1818, there were 32 factories containing 5,732 looms in the region.[60]

The Horrocks loom was viable, but it was the Roberts Loom in 1830 that marked the turning point.[61][clarification needed] Incremental changes to the three motions continued to be made. The problems of sizing, stop-motions, consistent take-up, and a temple to maintain the width remained. In 1841, Kenworthy and Bullough produced the Lancashire Loom[62] which was self-acting or semi-automatic. This enabled a youngster to run six looms at the same time. Thus, for simple calicos, the power loom became more economical to run than the handloom – with complex patterning that used a dobby or Jacquard head, jobs were still put out to handloom weavers until the 1870s. Incremental changes were made such as the Dickinson Loom, culminating in the fully automatic Northrop Loom, developed by the Keighley-born inventor Northrop, who was working for the Draper Corporation in Hopedale. This loom recharged the shuttle when the pirn was empty. The Draper E and X models became the leading products from 1909. They were challenged by synthetic fibres such as rayon.[63]

By 1942, faster, more efficient, and shuttleless Sulzer and rapier looms had been introduced.[64]

Symbolism and cultural significance

The loom is a symbol of cosmic creation and the structure upon which individual destiny is woven. This symbolism is encapsulated in the classical myth of Arachne who was changed into a spider by the goddess Athena, who was jealous of her skill at the godlike craft of weaving.[65] In Maya civilization the goddess Ixchel taught the first woman how to weave at the beginning of time.[66]

Gallery

- Model of Navajo Loom, late 19th century, Brooklyn Museum

- An early nineteenth century Japanese loom with several heddles, which the weaver controls with her foot

- A Jakaltek Maya brocades a hair sash on a back strap loom.

- Handloom at Hjerl Hede, Denmark, showing grayish warp threads (back) and cloth woven with red filling yarn (front)

- Oaxacan artisan Alberto Sanchez Martinez at loom

- Handloom at the Korkosz Croft in Czarna Góra, Poland, 19th century

- Weaver from India showing handloom during an exhibition

- A Grecian urn showing a warp-weighted loom

See also

- Bunkar: The Last of the Varanasi Weavers (documentary film)

- Fashion and Textile Museum

- Textile manufacturing

- Timeline of clothing and textiles technology

- Weaving (mythology)

References

- ^ "loom". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "loom - Origin and meaning of loom by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ "warp - Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ a b Collier 1970, p. 104.

- ^ Najeeb, Hana (22 December 2023). "Hands On Heritage - Navajo Loom and Backstrap Weaving". Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "Backstrap Looms". Sam Noble Museum. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Article describing the experimental reconstruction of the 6th-7th century Anglo-Saxon warp-weighted loom from Pakenham, Suffolk

- ^ Luisa (29 January 2018). "DIY WEAVING LOOM WITH HEDDLE BAR". Why Don't You Make Me?. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "HOW TO WARP A FRAME LOOM WITH A HEDDLE BAR". Kaliko. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Darning Mini Wooden Loom Machine". Miupie. (commercial site, but with animation showing how it works), Morley, Jasmin (8 September 2022). "Darning Loom Instructions". Purl and Friends. Retrieved 7 January 2023., [not given], Allison (27 December 2021). "Darning loom". On the Needles. Retrieved 7 January 2023., "How To Use A 1940s "Speed weve" Darner [repost of original 1940s instruction manual]". Rag & Magpie. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Wood, Errol. "11. Weaving technologies and structures". Wool Processing (PDF). Retrieved 4 December 2024 – via Woolwise.

- ^ "Learn to weave on the Brooklyn Four Shaft Loom" (PDF). Ashford. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Types of Looms | Learning About Looms". Glimakra USA. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e van der Hoogt, Madelyn. "Ask Madelyn: Jack Looms and Counterbalance Looms". Handwoven Magazine. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Different types of looms – Jane Stafford Textiles". janestaffordtextiles.com. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Joanne, Hall (30 May 2019). "Jack Looms - part 1". Fiberarts.org. Fiber Arts. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ Onuegbu, GC; Nnorom, OO; Okonkwo, Samuel Nonso; Ojiaku, PC (2020). "Diaper Design for Polyester Fabric" (PDF). J Textile Sci Eng. 10 (3). doi:10.37421/jtese.2020.10.408 (inactive 5 December 2024). Retrieved 3 December 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e XENAKIS, DAVID. "ABOUT TYING UP A COUNTERMARCH LOOM" (PDF). Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Different types of looms – Jane Stafford Textiles". janestaffordtextiles.com. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Counterbalance Loom, Jack-Type loom, Countermarch loom and NEW Jack-Type loom with back hinge treadle: TECHNICAL INFORMATIONS". www.leclerclooms.com. LeClerc Looms. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Burnham 1980, p. 48.

- ^ a b Broudy 1979, p. 124.

- ^ Forbes 1987, pp. 218, 220.

- ^ a b Ceccarelli, Marco; López-Cajún, Carlos (2012). Explorations in the History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings of HMM2012 (History of Mechanism and Machine Science). Springer. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-9400799448.

- ^ Usher, Abbott Payson (2011). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Dover Publications. p. 54. ISBN 978-0486255934.

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric (2008) [1962]. The Age of Revolution. London: Abacus. p. 45.

- ^ "Fabric Glossary". Christina Lynn. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Razy 1913, p. 120.

- ^ Geselowitz, Michael N. (18 July 2016). "The Jacquard Loom: A Driver of the Industrial Revolution". The Institute: The IEEE news source. IEEE. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Tapestry Weaving with Soumak". Between and Etc.

- ^ Churchill Candee, Helen (1912). The Tapestry Book (The Project Gutenberg eBook [EBook #26151] ed.). Fredrick A. Stokes.

- ^ "Choosing the Right Shuttle for the Job". Schacht Spindle Company. 20 December 2021.

- ^ a b Moncreif, Liz. "Choosing and Using Shuttles: Stick Shuttles, Flat Shuttles, and Rag Shuttles". Handwoven Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Moncreif, Liz. "Choosing and Using Shuttles: Rug and Ski". Handwoven Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Moncreif, Liz. "Choosing and Using Shuttles—Boat Shuttles, Bobbins, and Quills". Handwoven Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Moncreif, Liz. "Choosing and Using Shuttles: Double-Bobbin Boat Shuttles and End-Feed Shuttles". Handwoven Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Weaving Shuttles". Bluster Bay Woodworks.

- ^ Rajagopalan, S. "Advances in Weaving Technology and Looms". S.S.M. College of Engineering, Komarapalayam. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010 – via Pdexcil.org.

- ^ "Circular Looms". Starlinger. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Koster, Joan (1978). Handloom Construction: A Practical Guide for the Non-Expert. Volunteers in Technical Assistance, Inc. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- ^ Kent, Kate P. (1957). "The Cultivation and Weaving of Cotton in the Prehistoric Southwestern United States". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 47 (3): 485. doi:10.2307/1005732. hdl:2027/mdp.39015017458095. JSTOR 1005732.

- ^ Centre, ARTISANS' (21 June 2023). "Around the World: Backstrap and Heddle Loom Weaving". ARTISANS' CENTER. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Backstrap Looms". Sam Noble Museum. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Lush, Emily (9 December 2017). "Making of: T'nalak Weaving, Philippines". The Textile Atlas. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Abaca". White Champa. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Edwards, A. Cecil (1975). The Persian carpet : a survey of the carpet-weaving industry of Persia (Reprinted 1952 ed.). London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0715602560.

- ^ "Types of carpets loom and knowledge of its components". Farahan Carpet. 18 April 2021.

- ^ Bruno, Leonard C.; Olendorf, Donna (1997). Science and technology firsts. Gale Research. p. 2. ISBN 9780787602567.

4400 B.C. Earliest evidence of the use of a horizontal loom is its depiction on a pottery dish found in Egypt and dated to this time. These first true frame looms are equipped with foot pedals to lift the warp threads, leaving the weaver's hands free to pass and beat the weft thread.

- ^ a b "Know Your Handlooms". DAMA Handloom Store. 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "Handloom VS Powerloom". 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-12-01.

- ^ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bas-lisse and the other 3 entries

- ^ On darning loom function:

- "Darning Mini Wooden Loom Machine". Miupie. (commercial site, but with animation showing how it works)

- Morley, Jasmin (8 September 2022). "Darning Loom Instructions". Purl and Friends. Retrieved 7 January 2023., [not given], Allison (27 December 2021). "Darning loom". On the Needles. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- "How To Use A 1940s "Speed weve" Darner [repost of original 1940s instruction manual]". Rag & Magpie. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Katrinkles Darning Loom". Around the Table Yarns. (darning loom without heddles, just a comb, for knits).

- ^ Boyne, Jo (3 October 2021). "How To Use A Speedweve Loom To Mend Clothes ⋆ A Rose Tinted World". A Rose Tinted World. Retrieved 9 December 2022. (not an independent source)

- ^ "the Swift Darning Loom from Worth Mending". Worth Mending.

- ^ "Make Your Own Darning Looms". Instructables.

- ^ "Speedweve Style Darning Loom | Glowforge". glowforge.com.

- ^ Jocelyn C. (22 December 2008). How to: Cast on/Knit using a Circular Loom. Archived from the original on 2021-11-14. Retrieved 27 June 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Marsden 1895, p. 57.

- ^ Guest 1823, p. 46.

- ^ Marsden 1895, p. 76.

- ^ Marsden 1895, p. 94.

- ^ Mass 1990.

- ^ Collier 1970, p. 111.

- ^ Tresidder, Jack (1997). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Symbols. London: Helicon Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 1-85986-059-1.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Brenda P. (1990). "Mayan Women, Weaving and Ethnic Identity: a Historical Essay". Guatemala: Museo Ixchel del Traje Indigena: 157–169.

Bibliography

- Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00224-X.

- Broudy, Eric (1979). The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present. Hanover and London: University Press of New England. ISBN 9780874516494.

- Burnham, Dorothy K. (1980). Warp and Weft: A Textile Terminology. Royal Ontario Museum. ISBN 0-88854-256-9.

- Collier, Ann M. (1970). A Handbook of Textiles. Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-018057-4.

- Crowfoot, Grace (November 1937). "Of the Warp-Weighted Loom". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 37: 36–47. doi:10.1017/s0068245400017950. S2CID 193172489.

- Forbes, R. J. (1987). Studies in Ancient Technology, Volume 4. Leiden / New York: E. J. Brill. ISBN 9004083073.

- Guest, Richard (1823). The Compendious History of Cotton-Manufacture. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- Marsden, Richard (1895). Cotton Weaving: Its Development, Principles, and Practice. George Bell & Sons. Archived from the original on 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Mass, William (1990). "The Decline of a Technology Leader:Capability, strategy and shuttleless Weaving" (PDF). Business and Economic History. ISSN 0894-6825. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-04-29.

- Razy, C. (1913). Étude analytique des petits modèles de métiers exposés au musée des tissus (in French). Lyon, France: Musée historique des tissus.

- Ventura, Carol (2003). Maya Hair Sashes Backstrap Woven in Jacaltenango, Guatemala, Cintas Mayas tejidas con el telar de cintura en Jacaltenango, Guatemala. Carol Ventura. ISBN 0-9721253-1-0.

External links

- Loom demonstration video

- "Caring for your loom" article

- "The Art and History of Weaving"

- The Medieval Technology Pages: "The Horizontal Loom"

![Shuttles are passed, not thrown, through warp-weighted looms. These Ancient Greek weavers have a yarn-wrapped stick.[7]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Greekurnwithweavers_%28cropped_to_warp-weighted_loom%29.jpg/191px-Greekurnwithweavers_%28cropped_to_warp-weighted_loom%29.jpg)

![Belt or band shuttle, a short shuttle used for inkle weaving. This extra-sturdy shuttle is also used at a batten, to beat the newly woven weft against the previously woven fell.[32]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Chantier_de_fouilles_%C3%A0_Morigny-Champigny_en_juin_2012_20.jpg/270px-Chantier_de_fouilles_%C3%A0_Morigny-Champigny_en_juin_2012_20.jpg)

![Netting shuttle.[33] Also used for netting.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/Weaving_tool_%28AM_8823-1%29.jpg/240px-Weaving_tool_%28AM_8823-1%29.jpg)

![Ski shuttle.[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/V%C3%A4v%2C_Mattgarnsskyttel.jpg)

![A rag shuttle has two skis; it is used for weaving strips of rag into carpets, whence the name.[33]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Weavers_at_work_LOC_2163450764_%28cropped_to_rag_shuttle%29.jpg/145px-Weavers_at_work_LOC_2163450764_%28cropped_to_rag_shuttle%29.jpg)

![T'boli dream weavers using two-bar bamboo backstrap looms (legogong) to weave t'nalak cloth from abacá fiber. One bar is attached to the ceiling of the traditional T'boli longhouse, while the other is attached to the lower back. The cloth is being patterned by dying the warp, so the loom equipment is simple; a heddle rod, a shedding stick, and a batten. She is also using a footrest. Philippines.[44][45]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/T%27nalak_weaver_at_Lake_Sebu%2C_South_Cotabato.jpg/453px-T%27nalak_weaver_at_Lake_Sebu%2C_South_Cotabato.jpg)