Draft:Architecture of Guimarães

Comment: In Template:Cite web, "website=" is followed by the title of the website, not its domain name (unless, of course, the domain name is the title). Hoary (talk) 05:47, 10 September 2024 (UTC)

Comment: In Template:Cite web, "website=" is followed by the title of the website, not its domain name (unless, of course, the domain name is the title). Hoary (talk) 05:47, 10 September 2024 (UTC)

Comment: See the previous comment for info on resubmitting it. OhHaiMark (talk) 16:13, 9 September 2024 (UTC)

Comment: See the previous comment for info on resubmitting it. OhHaiMark (talk) 16:13, 9 September 2024 (UTC)

Comment: First, what are meant by "CAPELO et al, 1994" and "CRUZ, 2020"?Secondly, the lead seems to promise at least a brief description of Rococo, Neoclassical, and Contemporary styles. In order for this draft to be promoted to full article status, it's not necessary for the coverage of each of these (or others) to be fleshed out (this can come later); but it's very odd for coverage to reach the Manueline and there to simply stop. Hoary (talk) 06:13, 8 September 2024 (UTC)

Comment: First, what are meant by "CAPELO et al, 1994" and "CRUZ, 2020"?Secondly, the lead seems to promise at least a brief description of Rococo, Neoclassical, and Contemporary styles. In order for this draft to be promoted to full article status, it's not necessary for the coverage of each of these (or others) to be fleshed out (this can come later); but it's very odd for coverage to reach the Manueline and there to simply stop. Hoary (talk) 06:13, 8 September 2024 (UTC)

The architecture of Guimarães (Portugal) represents a blend of Medieval, Gothic, Neoclassical, and local styles. This variety is evident in the city's structures, such as the Castle of Guimarães and the Padrão do Salado, as well as in its Renaissance and Rococo buildings, which extensively use the abundant local granite. The Historic Centre of Guimarães, where are found buildings that follow every major architectural style from the Romanesque to the Contemporary, was declared a World Heritage Site in 2001 and later expanded in 2023 due to its extremely well preserved state and size.[1]

Castro architecture

Pre-Roman settlement

During the Castro culture era, stonework became mainstream, a stage towards the construction of granite houses, sturdier and more stable than their wood and hay counterparts.

The Citânia de Briteiros, a mere 9km from Guimarães and considered the city’s predecessor (even though other settlements in the area exist such as the Citânia de Sabroso), dates back to the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, when several panels with rock engravings were carved into the granite cliffs of the eastern slope of the castro settlement.[2] Permanent habitation of the site can be dated back to the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, falling within the period known as the Atlantic Bronze Age.[2] The Citânia's golden phase extends from the 2nd century BC to the change of era, and it was still inhabited after the integration of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula into the Roman Empire, during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In the 10th century, a small Christian hermitage was built on the acropolis, among the rubble of the old settlement.[2]

One characteristic from these settlements are the Pedras formosas ("beauty stones"). These were elaborated and sculpted slabs used as door frames for the inner room.[3] Another characteristic element of Castro culture was warrior statues, representations of the leaders and glorification of the ancestors, which evolved from the stele statues of the Bronze Age and later became associated with Mediterranean and Celtic elements.

Roman conquest and decline

The territory was definitively conquered by Roman troops around 19 BC, After a conflict that lasted around two hundred years.[4] During this process, the inhabitants of Citânia de Briteiros were connected to other regions already under Roman rule, as can be seen by the presence of many fragments of wine amphorae from Baetica, which had been taken by the forces of Julius Caesar in 61 BC.[5] The site of Citânia de Briteiros may not have been taken through a military campaign, but through a more peaceful integration into the Roman sphere of control, a process that would have been facilitated by trade and agreements with the authorities. This theory is reinforced by the presence of trade links between the region and neighboring territories already controlled by Rome, in addition to the fact that there are no documentary records of battles of note in this area during this period.[6]

Characteristics

Buildings in the Citânias are typically circular, with diameters of between 4 and 5 meters and with walls 30 to 40 cm thick. The granite rocks were split and placed in two lines, with the smoother side on the outside and the inside of the house.[7] The settlements are usually surrounded by a thick stone wall,[8] with the Citânia de Briteiros even having four distinct ones.[9]

|

Roman architecture

Little in Guimarães is Roman; however, some bridges, notably the Roman Bridge of Negrelos and the Taipas Bridge, are landmarks from that era.

Romanesque architecture

Many buildings in Guimarães follow Romanesque architecture. The earliest constructions in the city were built in this style, serving as models for later buildings not built during the typical Romanesque era but following the style.

|

Gothic architecture

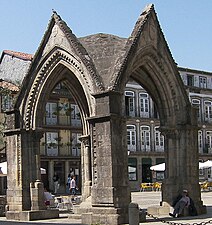

The Historic Centre of Guimarães is rich with Gothic buildings and structures. The city's main landmarks, such as the Castle of Guimarães, the Padrão do Salado, the medieval walls, and numerous religious buildings, all exemplify this architectural style.

|

Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture in Guimarães never had the same scale as in the nation's larger cities such as Lisbon or Porto; however, some religious and one urban examples show that this era still impacted the city.

Since Guimarães was relatively isolated during the Renaissance, the buildings had to rely heavily on local resources, with granite being the predominant material. As a result, the Renaissance architecture in the city is significantly influenced by granite.

Examples of this architectural style include the Santa Marinha da Costa Monastery[11] and the Capuchos Convent,[12] both religious. The Padrão de D. João I[13] and the Toural Fountain stand as notable monuments of this style, while the Casa Mota-Prego represents the only urban example of this architectural influence in the city.[14]

Although the Renaissance buildings in Guimarães may not resemble traditional Renaissance architecture at first glance due to the heavy presence of granite, they still retain many of the style's defining characteristics.

|

Manueline architecture

Manueline architecture is present in Guimarães via the Paço dos Duques, a 15th century palace with gothic and Romanesque influences,[16] as well as the Torre dos Mirandas, with its Manueline window.

|

See also

References

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historic Centre of Guimarães and Couros Zone". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ a b c "Citânia de Briteiros · Sociedade Martins Sarmento". www.csarmento.uminho.pt. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ "Pedra Formosa · Sociedade Martins Sarmento". www.csarmento.uminho.pt. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ CAPELO et al, 1994:9-10

- ^ CRUZ, 2020:128-130

- ^ CRUZ, 2020:130-132

- ^ Flores Gomes, José Manuel; Carneiro, Deolinda (2005). Subtus Montis Terroso — Património Arqueológico no Concelho da Póvoa de Varzim (in Portuguese). CMPV.

- ^ "Citânia de Sabroso". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Citânia de Briteiros". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Mosteiro de São Torcato / Igreja Paroquial de São Torcato". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Mosteiro de Santa Marinha da Costa / Igreja Paroquial da Costa / Pousada de Santa Marinha". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Convento de Santo António dos Capuchos / Igreja e Hospital de Santo António dos Capuchos / Hospital Velho de Guimarães". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Padrão de D. João I / Padrão de São Lázaro / Padrão dos Pombais". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Casa Mota-Prego / Casa dos Carvalhos". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico (in Portuguese). Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Monumentos".

- ^ a b "Paço dos Duques de Bragança / Residência Oficial do Presidente da República / Museu". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitetónico. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

![11th century Chapel of São Torcato, modified in the 1800s[10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Capela_de_S%C3%A3o_Torcato.jpg/169px-Capela_de_S%C3%A3o_Torcato.jpg)

![The Mosteiro de Santa Marinha da Costa [pt], originally built in the Romanesque style, now a prime example of Renaissance architecture using the abundant local granite](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Igreja_do_Mosteiro_de_Santa_Marinha_da_Costa_%2845806655804%29.jpg/337px-Igreja_do_Mosteiro_de_Santa_Marinha_da_Costa_%2845806655804%29.jpg)

![Built in 1585 in the Toural, the Toural Fountain was moved to the Carmo Square in 1891, but was moved back in 2011[15]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/Chafariz_do_Largo_do_Toural_%2839751648123%29_%28cropped%29.jpg/254px-Chafariz_do_Largo_do_Toural_%2839751648123%29_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Although the Palace of the Dukes of Braganza suffered massive restoration works from 1937 to 1959,[16] it follows the Manueline style with heavy Gothic influence](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Guimar%C3%A3es-Pa%C3%A7o_Ducal-2.jpg/300px-Guimar%C3%A3es-Pa%C3%A7o_Ducal-2.jpg)