Doorbell

A doorbell is a signaling device typically placed near a door to a building's entrance. When a visitor presses a button, the bell rings inside the building, alerting the occupant to the presence of the visitor. Although the first doorbells were mechanical, activated by pulling a cord connected to a bell, modern doorbells are electric, operated by a pushbutton switch. Modern doorbells often incorporate intercoms and miniature video cameras to increase security.

History

William Murdoch, a Scottish inventor, installed a number of his own innovations in his house, built in Birmingham in 1817; one of these was a loud doorbell, that worked using a piped system of compressed air.[1] A precursor to the electric doorbell, specifically a bell that could be rung at a distance via an electric wire, was invented by Joseph Henry around 1831.[2] By the early 1900s, electric doorbells had become commonplace.

Wired doorbells

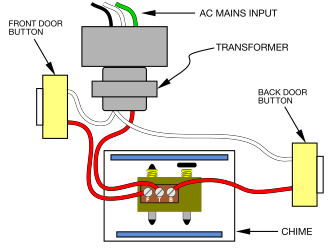

In most wired systems, a button on the outside next to the door, located around the height of the doorknob, activates a signaling device (usually a chime, bell, or buzzer) inside the building. Pressing the doorbell button, a single-pole, single-throw (SPST) pushbutton switch momentarily closes the doorbell circuit. One terminal of this button is wired to a terminal on a transformer. A doorbell transformer steps down the 120 or 240-volt AC electrical power to a lower voltage, typically 6 to 24 volts. The transformer's other terminal connects to one of three terminals on the signaling device. Another terminal is connected to a wire that travels to the other terminal on the button. Some signaling devices have a third terminal, which produces a different sound. If there is another doorbell button (typically near a back door), it is connected between the transformer and the third terminal. The transformer primary winding, being energized continuously, does consume a small amount (about 1 to 2 watts) of standby power constantly; systems with lighted pushbutton switches may consume a similar amount of power per switch.[3][4] The tradeoff is that the wiring to the button carries only safe, low-voltage power isolated from earth ground.

A common signaling device is a chime unit consisting of two flat metal bar resonators, which are struck by a plunger operated by a solenoid. The flat bars are tuned to two pleasing notes. When the doorbell button is pressed, the solenoid's plunger strikes one bar, and when the button is released, a spring on the plunger pushes the plunger back, causing it to strike the other bar, creating a two-tone sound ("ding-dong"). If a second doorbell button is used, it might be wired to a second solenoid, which strikes only one of the bars, to create a single-tone sound ("ding"). Alternatively, the second button might feed the single solenoid via an oscillating switch (often a mercury tilt switch), to give a "warbling" sound ("ding-dong-ding-dong-ding-dong"). The Edwards Sylvan C-26 had both additional features, suiting three doors.[5] Some chimes have tubular bells instead of bars.

More elaborate doorbell chimes play a short musical tune, such as the Westminster Quarters.

Doorbells for hearing-impaired people use visual signaling devices — typically light bulbs — rather than audible signaling devices.[6][7]

Fully battery-powered wired models are also common, either using a two-bar design or an electric bell. These do not consume standby power, but require the user to change the batteries, which are usually large primary cells located in the bell box.

Wireless doorbells

In recent decades, wireless doorbells have become popular, to avoid the expense of running wires through the building walls. The doorbell button contains a built-in radio transmitter powered by a battery. When the button is pushed, the transmitter sends a radio signal to the receiver unit, which is plugged into a wall outlet inside the building. When the radio signal is detected by the receiver, it activates a sound chip that plays the sound of gongs through a loudspeaker—either a two-note "ding-dong" sound, or a longer chime sequence such as the Westminster Quarters. Frequencies in the 2.4 GHz ISM band are usually used. To avoid interference by nearby wireless doorbells on the same radio frequency, the units can usually be set by the owner to different radio channels.

In larger metropolitan cities, a trend has developed over the past decade that uses telephone technology to wirelessly signal doorbells, as well as to answer the doors and remotely release electric strikes. In many cities throughout the world, this is the predominant form of doorbell signalling.

Musical and continuous power doorbells

As with wireless doorbells, musical doorbells have also become more common. Musical and continuous power doorbells serve as an attempt to bridge the gap between newer digital circuitry and older doorbell wiring schemes. A major difference between the standard setup of a wired doorbell and a musical doorbell is that the musical doorbell must maintain power after the doorbell button is released, to continue playing the doorbell song. This can be achieved in one of two ways.

For simple single-pole, single-throw doorbell buttons, the chime device employs a rectifier diode and ballast capacitor at the voltage input stage of the circuit. Upon pressing the doorbell button, power is connected through the rectifier diode or series of rectifier diodes called a full wave rectifier, which allows the current to flow in only one direction, into the ballast capacitor. The ballast capacitor charges at a rate far greater than the rest of the circuit needs to complete a given song. Once the button is released, the capacitor retains the charge and maintains power for a short duration to the rest of the circuit.

For mixed wireless and wired input doorbells, a special doorbell button is needed to maintain power continuously to the doorbell chime. The circuit is similar to the one above, except that the rectifier diode is now moved into the doorbell button housing. Pressing the doorbell button allows both negative and positive sides of the AC power signal to flow into the circuit, while releasing the button only allows either the positive or negative side to flow into the circuit. By differentiating the full and half wave signals, the doorbell is able to function as it does in the previous wired case, while also providing continuous power to the doorbell for other purposes, such as receiving wireless doorbell button input.

Smart doorbells

With the rise of the Internet of Things in the 2010s, a number of internet-connected bell systems, known as smart doorbells have appeared on the market.

Popular systems include the Ring doorbell, Vivint Home Security doorbell, and the Nest Hello. These consist of a single unit which is located in place of the traditional push-button, and in addition to a physical button, contains a high-definition camera, passive infrared sensor and Wi-Fi capability. The device is connected to the home Wi-Fi network, and notifications of a button-press or detected movement are pushed to a paired smartphone or other electronic device such as a tablet. When a notification is received, the user will typically see a live video stream from the smart doorbell, showing who is at the door and potentially allowing a 2-way audio conversation.

The devices can be powered by an internal battery, or they may use the existing bell wiring for continuous power.

The video is typically recorded via Wi-Fi to a cloud internet service, meaning that if the unit is tampered with, damaged or stolen, then this recording will still be captured and can be analyzed to determine the identity of the responsible party.[8]

See also

- Bell pull

- Call bell – a counter top bell used to call attention of the staff at a service desk

- Door knocker

- Intercom

References

- ^ "Scottish Inventions and Discoveries — Coal Gas Lighting — William Murdoch (1754–1839)".

- ^ Scientific writings of Joseph Henry, Volume 30, Issue 2. Smithsonian Institution. 1886. p. 434. ISBN 9780598400116.

- ^ "Why Did President Bush Suddenly Start Talking about Standby Power?", a PowerPoint slide presentation by Alan Meier. https://www.energystar.gov/ia/partners/prod_development/downloads/power_supplies/PSPresent2.ppt energystar.gov

- ^ Miscellaneous Electricity Use In U.S. Homes Marla C. Sanchez, Jonathan G. Koomey, Mithra M. Moezzi, Alan Meier and Wolfgang Huber, LBNL Berkeley California, https://www.osti.gov/bridge/servlets/purl/795945-9c8LM1/native/795945.pdf osti.gov

- ^ "Edwards Sylvan C-26".

- ^ "Alerting and Communicating Devices for Deaf and Hard of Hearing People — What's Available Now". Clerccenter.gallaudet.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- ^ "NPR — At Gallaudet, a Turn Inward Opens New Worlds". Npr.org. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- ^ Tilley, Aaron. "Here come the internet connected doorbells". Forbes. Retrieved 16 November 2018.