Dixon Bridge Disaster

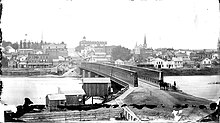

The Dixon (Ill.) Truesdell Bridge Collapse, May 1873. View: looking north | |

| Date | May 4, 1873 |

|---|---|

| Location | Dixon, Illinois, US |

| Coordinates | 41°50′41″N 89°29′04″W / 41.844830°N 89.484430°W |

| Also known as | Truesdell Bridge Disaster |

| Type | Bridge disaster |

| Cause | Bridge design flaw |

| Deaths | 46 |

| Non-fatal injuries | at least 56 |

The Dixon Bridge Disaster, also known as the Truesdell Bridge Disaster, occurred on Sunday, May 4, 1873, when the bridge across the Rock River at Dixon, Illinois, collapsed while spectators were observing a baptism ceremony in the river below. The collapse killed 46 people and injured at least 56 others. In terms of total deaths and injuries, the event may be the worst road bridge disaster in American history.

A coroner's jury ruled that the Dixon City Council erred in judgment in selecting the Truesdell bridge design, which was determined to be faulty.

Dixon in 1873

At the time of the collapse, Dixon was a growing town and a primary crossing point over the Rock River for those traveling from downstate Illinois to Galena, Illinois. In 1870, the population of Dixon was 4,055, almost double its population in 1860.

The city was served by a mayor and eight aldermen, seven churches, and two weekly newspapers, The Dixon Sun and The Dixon Telegraph. In the five years prior to 1873, the city had enjoyed a significant growth of construction and infrastructure. The city had two bridges: a railroad bridge built in 1855 and a bridge for pedestrians and vehicles. Most residents lived within 10 blocks of the vehicular bridge.

From the city's founding in 1830 until 1846, residents crossed the river primarily by ferry. Between 1846 and 1868, the city had at least eight wooden bridges across the Rock River. None of them survived more than a few years, usually being destroyed by the high water and floating ice jams that occurred each spring.[1]

Construction of bridge

In 1868, after another bridge failure, the city sought a more durable solution and accepted bids from 14 contractors. In May 1868, the Dixon bridge committee had personally visited many of the proposed bridge designs.[2]

Bridge contractor L. E. Truesdell, originally of Warren, Mass., had proposed an iron bridge that was based on his 1856 patent for a lattice bridge design. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Truesdell's design was built on the idea that “an iron bridge might be built of short light pieces, easy of transportation to the almost inaccessible localities where bridges might be needed.”[3] As of 1868, Truesdell had built several bridges in Illinois, but none as long as the proposed 660' bridge in Dixon.[4] The Decatur (Ill.) Republican reported, “Mr. Truesdell warrants every bridge to give perfect satisfaction. … He certainly has the best thing yet out … They are unequalled for strength and symmetry and are rapidly growing into favor.”[5]

The Dixon city council took three ballots before finally favoring the Truesdell bid on a 5-3 vote. As Alderman W. N. Underwood Jr. recalled in the Inter-Ocean newspaper, “The people were crazy on (an) iron bridge.”[2]

When the Truesdell project, a toll bridge, was dedicated on Jan. 21, 1869, the Dixon Weekly Herald reported, “A structure more truly grand and beautiful to the eye can be found in no Western city and we presume in no Eastern one.”[6] The bridge featured five 132 foot (40 m) spans, an 18-foot-wide (5.5 m) roadway with two 5 foot (1.5 m) sidewalks on both sides, each guarded with a 3 foot (0.91 m) railing. The project cost the city $75,000,[7] which included $31,500 for the ironwork and $43,500 for the five stone piers that supported the structure.

The 1869 dedication included a 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) long parade and included a test of the bridge by placing on the bridge four harnessed teams hauling stone, a load of flour, and a large group of bystanders, all weighing “at least 45 tons.”[6] The Belvidere (Ill.) newspaper later reported that the Dixon city council issued a resolution that thanked Truesdell “for the promptness, energy, and faithfulness … and also for his gentlemanly courtesy.”[8]

Elgin bridge collapse

While the Dixon bridge was being completed, a portion of the Truesdell bridge at Elgin, Illinois, collapsed on Dec. 7, 1868.[9] It was repaired, but seven months later, on July 5, 1869, the Elgin bridge partially collapsed again while filled with people watching a tub race. A 68 foot (21 m) span on the bridge's east side fell into 4 foot (1.2 m) of water. The number of deaths reported ranged 0–3, but 30 to 40 were injured.[10] The collapse would have raised concerns about the Dixon bridge, but the Elgin bridge was a single truss design, while the Dixon bridge was a double truss. This lessened apprehensions about the Dixon bridge.[2] When an investigation of the Elgin collapse began, L. E. Truesdell offered a reward of $10,000 for the detection of the guilty parties. The investigation concluded, “The foundations of the structure must have been tampered with by some evil disposed persons,” according to a Milwaukee newspaper.[11]

Dixon collapse

Sunday, May 4, 1873, was said to be a beautiful day after a cold winter. On May 4, word had spread around Dixon that Rev. J. H. Pratt of the Baptist Church was going to lead his congregation after services to the river to baptize six converts: one man and five women. The baptism site was on the north side of the river, “a few rods” (four rods are 20 m or 66 ft) west of the Truesdell bridge.[12]

Rev. Pratt later admitted to the Chicago Daily Tribune that he had detained the crowd longer than usual to impress upon them the advantage of ‘coming to Jesus.’ He added that he had no concerns of a bridge failure since he had conducted similar ceremonies at the same spot with “at least three times as many persons congregated on the same span to witness the immersion.”[13]

By various accounts, the bridge had filled with at least 150 to 200 spectators, with the heaviest concentration on the sidewalk between the riverbank and the first pier. Several horse-drawn carriages were on the bridge's roadway. While most spectators were reported to be women and children, some boys and a few men had climbed upon the bridge's 15-foot-high (4.6 m) trelliswork to get a good view.[12]

Rev. Pratt had baptized two of the six, and a lady named Mrs. Brewer was the third. As she and the minister waded out into the water, the choir began to sing. Some said that they felt the bridge vibrate, and others commented about the possibility of a collapse. Henry Strong, the bridge tender, reportedly began to order boys off the trusses and the people off the bridge.[12]

Failure of bridge

Many of the eyewitnesses reported hearing a sharp crack between the end of the bridge and the first pier. The heavy weight of the crowd on the west side seemed to tip the bridge over, as that part of the bridge dropped quickly. The crowd then uttered “one wild fearful shriek” as they plummeted about 18 feet (5.5 m) into the water, which was reported to be 15 to 20 feet (4.6 to 6.1 m) deep.[12] While the north span was the first to fall, the other four spans also quickly collapsed, with each span twisting in different directions. The Chicago Tribune reported, “Some sank to rise no more. Some were killed before they touched the water. Some were entangled in the debris. Some jumped from the bridge to the river, and swam ashore. The weak generally succumbed.” The 15 foot (4.6 m) truss “fell over with the weight, and imprisoned the doomed in an iron cage, with which they sunk, and from which there was no escape.” The hands and faces of some victims could be felt only six inches (150 mm) below the surface of the water, trapped under the debris.[3]

Several newspaper reports noted the ensuing panic in the water, as victims frantically grabbed at each other to get to the surface, while others fought off such grasps to avoid being pulled under. In the fall, children were separated from their parents, and wives were separated from their husbands.

Fatalities

The ironwork of the bridge created deadly problems. The iron latticework “pivoted like shears, catching many hands and mangling them.” A 16-year-old girl, who drowned, had her arm caught in the ironwork so that it took almost “two days to cut away the iron with hack saws and release her body,” according to the Dixon Telegraph.[14] Another woman had her leg sawed off to free it from the debris, while others were crushed by the ironwork. “Two women went down together, the iron hemming them in like a vise. Their necks and bodies were securely bound.”[3]

As of 6:00 p.m. that Sunday, 37 bodies had been pulled from the water. The total number lost was then estimated at 90 to 100, since many were assumed to be trapped under the heavy ironwork of the bridge.[15]

Injuries

Newspaper accounts reported dozens of injuries sustained by survivors. The injuries included severe wounds to the scalp, head, leg, arm, wrist, collar bone, shoulder, ribs, chest, spine, various bones, as well as shock and severe lacerations. Reports also mentioned several cases of “strangulation” that cut off breathing, yet not fatally. One such strangulation survivor was the youngest reported injury, 3+1⁄2-year-old Gertie Wadsworth, daughter of John Wadsworth. She had been on the bridge with her grandmother, Christan Goble, who was killed.[16]

Similarly, Elizabeth Wallace fell to the water holding her daughter. The mother died, but the daughter was expected “to live a cripple if she survives the spasms into which she is constantly thrown. She is now an orphan,” reported the Inter-Ocean.[17] Similar psychological injuries were reported by the Dixon Sun: “Kittie Dally was “insensible from strangulation in the water. Frank Bisco in the same condition.”[16] The Sun listed the names of 56 injured, which included 31 males and 25 females.[18]

Rescue efforts

As the mass of bodies were thrown into the river, several citizens quickly brought ropes, planks, and boats to rescue the living and recover the dead. One boat retrieved two little sisters who had clung to each other and to a portion of the ironwork of the bridge.[15] When the bridge collapsed, long wooden planks that made up the bridge floor were released into the water, becoming life rafts for those who grabbed one.[3] Others used the planks to extend a lifeline to those in the water. William Dailey was reported to have saved 16 victims using one of these planks.[14] Several men worked tirelessly with rescue efforts, while many homes along the river were opened up to the dead and the wounded. As reported by the Dixon Sun, many citizens “did not spare their substance during our trouble. Blankets, shawls, clothing, sheets, quilts, cloths, cotton, woolen goods, and materials of every description were demanded and were freely given and without a question. The houses were filled with the dead, the dying, and with a thousand anxious enquirers. Carpets and beds were given up freely, and services rendered that ought to give us a nobler estimate of humanity than has ever entered our conceptions.”[18]

Survivor stories

The extensive newspaper coverage of the event included many survivor stories. The Memphis Daily Appeal reported: “There were a number of remarkable escapes of children, of whom there were probably about fifty on the bridge when it went down. One little fellow about thirteen years old was caught by both feet on the iron rigging of one of the fallen spans, and had one of his legs broken. He managed by sheer strength to pull one of his boots off, tearing the sole off in the process; then coolly taking out his knife, ripped the other boot from the foot of the wounded leg, and, crippled as he was, swam ashore.”[15]

Jacob Armstrong Jr., a shoemaker about 24 years old, went down in the crash and was reported to have crawled on the bottom of the river to escape the trappings of the bridge. He then went to work rescuing others.[19] In the Chicago Times, Armstrong was quoted as saying, “Under water there were women and children, and some men, all striving to clutch hold of something to save themselves. … They looked like dark objects wrestling about. Some poor fellow caught hold of me, and would have dragged me down, only I managed to get free and began striking out with my right hand.”[20]

Other young men were noted for their stories of survival and rescue. The Dixon Telegraph reported, “Will Schuler, Joe Haden, and Eustace Shaw narrowly escaped by swimming to the shore after extricating themselves from the iron work on leaping from the bridge into the river.”[19] Eustace Shaw, then only 16, would later become the editor of the Telegraph.[21] The Tribune reported that he could “swim like an otter.” After rescuing himself, “He … bravely sallied forth to rescue the drowning, bringing several to shore.”[3]

Some reporters became skeptical of the veracity of some survivor stories floating around town. As the Chicago Inter-Ocean reported, “Stories of miraculous escapes and adventures are more rife than ever, and when facts fail, the power of invention is brought into play, each fiction-monger endeavoring to make his more readable than the last.”[2]

Finding the missing

With the large number of bodies in the water and the river current estimated at 8 miles per hour (13 km/h), the community had difficulty accounting for the saved, the lost, and the missing. Even after a week of searching, at least five were still missing. For days, the river was dragged with a 300 foot (91 m) trolling line with grappling hooks.[22]

On May 15, 11 days after the accident, the Dixon Telegraph reported that all bodies had been recovered.[16] Five bodies were recovered more than 10 miles (16 km) downstream, the farthest being 17-year-old Lizzie Mackey, whose body was discovered by fishermen below the dam at Sterling, Illinois, 14 miles (23 km) down river.[23]

One of the last to be retrieved was the second daughter of Mrs. Hendrix, discovered about two or three miles (3.2 or 4.8 km) above Sterling. Alphea and Lucia Hendrix, ages 6 and 4, were the youngest fatalities. Their mother was a widow who lost her only two children in the disaster. Unable to afford a burial, a fund was raised to help her.[24]

Aftermath

The bridge collapse cut off access from the south side to the north side of the city. Most residents lived on the south side, opposite the primary site of the fatalities. The Chicago Daily Tribune said, “From early morning the banks were lined with spectators, and the ferry was engaged all day ferrying over caskets and mourning relatives of the departed.”[13] The Minneapolis Tribune, summarizing reports from the Chicago papers, reported about “the eager crowds that gathered around as (the bodies) were laid out cold and stiff in their Sunday raiment, the agonizing shriek that recognition evoked, the sobs of men, the swooning of women.” Corpses were then ferried across the river to families on the south side.[25]

On May 6, two days after the collapse, the Inter-Ocean reported that an estimated 10,000 people had come to view the ruins.[22] On the next day, the Inter-Ocean added, “The scene of the wreck has been visited to-day by thousands of people who have come by train from … Chicago, Geneva, Sterling, Amboy, Mendota, and other places along the railway lines.”[17] Before the city established a free ferry to facilitate crossing, “rapacious sharks (were) reaping a rich harvest by charging outrageous rates.”[17]

Business in town was suspended for several days, and schools were closed until further notice.[26] As the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported, “Though crowded, the streets are as silent as so many cemeteries. The people scarcely speak above their breath, and all discussion of the terrible subject which is uppermost in their minds is carefully avoided … Every window-blind is down, and on nearly every door the somber emblem of death is fluttering.”[25] This emblem was likely the draping of black crepe, a sign of mourning in that era.

Church bells tolled continually, as the streets were occupied with dozens of funeral processions in the days after the disaster, including 13 on Tuesday alone.[12]

Tally of the dead

Newspaper reports contained different totals of the number of fatalities. In the many published lists of the dead, 59 names were cited. But some names were later shown to be incorrect or duplicates. The best composite list contains 46 dead.

They are Eliza Alexander, Irene Baker, Malinda Carpenter, Henrietta Cheney, Mary Cook, Minnie Florence Dana, Emily Deming, Edward Doyle, the daughter of Edward Doyle, Ida Drew, Robert Dyke, Julia Gilman, Christan Goble, Thomas Haley, Frederick Halpe, Francis (Frank) Hamilton, Lucia Hendrix, Althea Hendrix, Nettie Hill, Millie Hoffman, Elizabeth Hope, George Kent, Pamelia Kentner, Sarah Latta, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Mackey, Sarah March, Jay Mason, Henrietta Merriman, Agnes Nixon, Jane Ann Noble, Maggie O'Brien, P. (son of Mrs. John) O'Neal, Allie Petersberger, Fannie Petersberger, Bessie Rayne, Mary Sillman, Rosa Stackpole, Clara Stackpole, Katie Sterling, Eliza M. Vann, Ida Vann, Ann Wade, Elizabeth Wallace, Seth H. Whitmore, Mrs. W. Wilcox, and Melissa Wilhelm.

All seven churches in town were busy with funerals, making the city's one cemetery among the most frequented spots in town. The Baptist church lost 14 lives (six women and eight children),[27] while the Universalist church incurred 15 losses. The Methodist church lost eight: five wives, two teenage girls, and one man. The Presbyterians lost three, St. Patrick's Catholic Church had four deaths, the Lutherans had two, and the Episcopalians lost one.[28] These numbers total 47, but since the names of each church's losses are not identified, two churches may have claimed the same person.

Of the 46 who died in the disaster, 37 (80%) were female and 9 (20%) were male. Many of the fatalities were youthful, as 19 of the 46 (41%) deaths were under 21 years of age, and three of those were under 10.

Word spreads

The news of the disaster spread quickly, via the primary communication means of telegraph. The Dixon Sun reported on May 7 that the story had found its way “around the globe.”[18] The news received prominent coverage throughout the nation in newspapers such as the New York Times, Washington (DC) Evening Star, Memphis Daily Appeal, Baltimore Sun, Detroit Free Press, New Orleans Times-Picayune, Philadelphia Inquirer, San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere.

The headlines revealed the drama of the event: “The Baptism of Death,”[12] “DEATH!"[29] “Fearful Horror,”[30] “The Great Disaster in Illinois,”[31] “Dixon’s Horror,”[32] “The Dixon Disaster,”[33] “The Great Bridge Murder,”[34] “A Bridge of Putty,”[35] “Terrible Calamity!”[36] “Rock River Bridge: Thrilling Account of the Fearful Disaster.”[37]

Placing blame

Immediately after the collapse, citizens and city officials began placing blame on various entities. Those blamed included L. E. Truesdell, the Dixon City Council, Henry Strong (the bridge tender), and the Baptists. While some of these were quickly dismissed, the case against L. E. Truesdell's bridge design sustained the test of time and scrutiny.

Baptists

Early critics quickly assigned blame to the Baptists for attracting people to their eventual doom. On May 6, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported: “One man sank twice and rose the third time, when a vain effort was made to grasp him. As he was going down he was heard to exclaim, ‘___ ____ the Baptists.’ With the curse on his lips, he sank forever.”[3]

On the following day, the Tribune’s story carried an editorial remark: “There are some people in this town—those in the habit of censuring Christians whenever they have an opportunity—who consider the Baptists, especially the Rev. J. H. Pratt, the minister who was immersing the converts, responsible for the accident. This is unfair …”[13]

As several newspaper stories noted, the Baptists had conducted a number of public baptisms in the river previously, attracting large crowds, but with no incidents or injuries.[38] Yet, the church suffered some repercussions after the tragedy. The church conducted no further baptisms in the river until a baptistery was installed in April 1876.[39] The health of J. H. Pratt quickly began to fail, and he resigned late that year. He continued in ministry elsewhere but died and was buried in 1883 at Dixon's Oakwood Cemetery, where he had buried several bridge victims only 10 years earlier.[40]

Claims of official misconduct

The press, still sensitive to misconduct by public officials from the Crédit Mobilier Scandal of 1872, quickly suspected that corruption was at the root of the Dixon debacle. On May 6, the Tribune reported:

We must look either to the criminal recklessness of officials who have authorized them, or to a system of lobbying that has secured their adoption. In either case, the authorities who authorized the building of the Dixon bridge must share with the contractors the responsibility of (the bridge disaster). … Thus must the Dixon disaster be traced ultimately to the corruption which pervades American official life.[3]

Locally, however, few Dixon citizens raised concerns about their elected officials who voted for the Truesdell bridge. A coroner's jury, convened on May 7, rendered a verdict that “the council erred in judgement in selecting the Truesdell Bridge” (Dixon Sun)[41] While Chicago papers were suspicious of corruption among Dixon officials, the two local newspapers largely defended the city council, but railed against Truesdell. On May 7, the Dixon Sun reported:

Give no ear to those men who accuse their neighbors of murder, as stated in the Chicago Times. Many good men believed the Truesdell bridge to be a perfect structure, and were as honest in their belief as those who were of a contrary opinion. Scientific men and bridge builders knew the faults of the miserable structure; and the rotten iron of which it was built was well known to the rotten contractors.[18]

Accusations of bribery

On May 7, Chicago's Inter-Ocean newspaper reported that, in New York, a letter had been published that “distinctly and explicitly charged that Truesdell obtained the contract for building the bridge … by bribery. It is said he bought four of the eight Aldermen of the city at prices ranging from $300 to $500 each.”[17]

These bribery allegations swirled briefly in newspapers outside Dixon, but locally, the charges gained little traction. On May 8, the Inter-Ocean backed off its allegations, noting that Judge John Eustace of Dixon “laughs at the charges.” The paper also noted that no accusations of bribery had been uttered prior to the bridge's fall. Most of the accused city officials submitted statements that no bribery was involved. At worst, it was thought that the bridge building committee was “bamboozled into a belief that Truesdell’s (design) was the best.”[2]

Coroner's jury testimony

At the May 7 coroner's jury, several local officials testified that there had been no previous concerns about the 4-year-old bridge. It had been carefully examined every year, and Henry Strong, the bridge tender, testified that there were three times as many people on the bridge only two weeks earlier. Jason Ayres, city clerk, said, “It was generally considered to a safe bridge; and people never hesitated to cross it” (Inter-Ocean).[2]

Nonetheless, many also testified of problems with the bridge. Ayres, for example, told the Tribune on May 6 that he had seen the bridge “shake and swing perceptibly to and fro with the weight of a wagon passing over it,” adding that the bridge was “frail and unsafe.”[3] The Tribune also reported that Col. John Dement, a highly respected citizen, had opposed the Truesdell bid in 1868 “because he believed it would be neither safe nor permanent, but the Council overruled his judgment and the judgment of other prominent citizens.”[3]

At the coroner's jury, several testified that the iron material was “bad” or “too light,” and they criticized the principles upon which the bridge was built. Since temperatures that winter had plummeted well below zero, others thought that the cold had negatively affected the strength of the iron.[42] M. B. Spafford, a local contractor (who had lost the bridge project to Truesdell), testified that the bridge materials and design were all unsafe. As reported in the Inter-Ocean, Spafford said, “The bridge was a humbug; it was not strong enough to hold itself up," and Clark Brown, a local machinist, testified that the “unequal distribution of heavy weight threw (the bridge) out of perpendicular and let it down.”[2]

Testimony of outside expert

On May 14, 10 days after the tragedy, the Dixon Sun tracked down L. Stanton, the city engineer at the time of the bridge's approval in 1868. Now living in Freeport, 35 miles (56 km) north of Dixon, Stanton had not been asked to testify to the coroner's jury. He said that he had firmly opposed the Truesdell bridge in 1868, but an alderman accused Stanton of being prejudiced against Truesdell's proposal. When the council voted to approve the iron bridge, Stanton was amazed. He said that he “never knew of an engineer or a practical bridge builder, living or dead, that approved of the plan upon which the Truesdell bridge was built.” He thought it was “the poorest of all” the proposals because the material was not of uniform size, and the latticework was not strong enough. When his input was not heeded, he would’ve resigned his position if he hadn’t been supported by City Attorney John V. Eustace and Alderman Porter.[41]

In an effort to collect other expert opinions about the Truesdell design, a Tribune reporter interviewed several prominent engineers in Chicago. Since some smaller Truesdell bridges had been built around Chicago, the engineers interviewed by the Tribune were aware of Truesdell's concept. One noted that it was not strange for city authorities to reject the advice of engineers. He explained, “(City officials) insisted on having their own way, and accused those who opposed them of advocating private interests and jobbery.”[3] Every Chicago engineer interviewed by the Tribune expressed “the unanimous verdict … that the State ought to cause the immediate destruction of every existing bridge of this pattern.” The Tribune report concluded that Truesdell “had the means to push his invention, and was thwarted only in the presence of men of science, who again and again declared it dangerous and useless. Every railroad company rejected it on sight.”[3]

Condemnation of Truesdell

For most of May, L. E. Truesdell was assumed to be dead. On May 6, the Tribune reported that he “deceased some years ago." With no one to defend his bridge design, the condemnations proceeded unhindered. The Tribune quoted J. K. Thompson, commissioner of the Chicago Board of Public Works, who said that Mr. Truesdell had succeeded in “foisting upon ignorant or unscrupulous authorities a miserable apology for a bridge. …” Another Chicago engineer pulled down from his library several books “until the whole book-case was exhausted, but no reference was made to the fancy man-trap discovered by Mr. Truesdell.”[3]

On May 7, the Dixon Sun quoted the Chicago Times as saying, “The question naturally boils up as to how long this firm of (debased) slaughterers is to be allowed to drown the citizens of Illinois.”[18] On May 8, the Sterling, Ill., newspaper wrote, “If Truesdell survives his wretched work, we recommend him to repair, at once, to Dixon and jump from the wreck into the river and stay there—or else quit building bridges.”[43]

In their condemnation, the newspapers published several creative names for the Truesdell bridge, such as “The Truesdell Trap” (Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6), “The Patent Wholesale Drowning Machine,” (Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6), “Truesdell’s Patent Death Trap,” (San Francisco Chronicle, May 13), “Godless sham,” (Decatur Local Review, May 22), “The horrible abortion” (Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph, May 10), and “Only suitable for a war measure to be used in an enemy’s country” (Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6).

Brother's response

While these harshly negative stories were being published, Truesdell's brother, W. H. Truesdell had been living in Belvidere, Ill., where much of Truesdell's operations had been based, about 50 miles (80 km) from Dixon. (Belvidere also had a Truesdell bridge of its own.) Finally, on May 13, W. H. Truesdell defended the bridge in an interview to the Belvidere newspaper: “Since the fall of the Dixon bridge, of course any number of ‘experts’ come to the surface with their ‘I told you so’s,’ and there has been the wildest newspaper exaggeration and abuse on the subject.”[8] Truesdell’s brother claimed that over 1,000 Truesdell bridges had been in daily use for 17 years around the country. (The claim was highly unlikely, since it implied that Truesdell had produced more than one bridge per week over that time period.) He added, “The Dixon bridge could never have broken by any such weight as 200 or 250 persons, unless some important parts of the iron work had been fractured by the frosts of the past severe winter. … If the city authorities had exercised due diligence in looking after its condition, the accident would never have happened, in all probability.”[8]

The rumors that L. E. Truesdell was dead proved false when he emerged from silence from his home in Massachusetts, sending a letter to the Springfield (Mass.) Republican, seeking “to vindicate his honesty and conscientious thoroughness in the construction of the bridge.” His defense was published elsewhere, including the New-York Tribune. He indignantly denied the charges of paying bribes and defied anyone to bring forth proof of such. “I know that I never made a better bridge than the one at Dixon in every particular,” he said, claiming that the 1869 test of the bridge weighed “at least 200,000 pounds … and yet it is said to have fallen with less than 15,000 pounds.” The only way the bridge could have fallen, he said, was if some of the bolts had been loosened.” He also claimed that an inspection of the Elgin bridge showed that “some of the bolts were missing and others were loosened.” He concluded his defense, saying, “It is nearly 18 years since I began building iron bridges, and the Elgin and Dixon bridges are the only ones that have fallen, and no loss of life except at Dixon. Can as much be said of any other plan?”[44]

Later life

In the 1860s, Lucius E. Truesdell had built several bridges in Illinois, including in Chicago (Kinzie St. and Wells St.), Belvidere, Pecatonica, Elgin, and Geneva.[5] The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that the two partial collapses of the Elgin bridge in Nov. 1868 and July 1869 “‘broke’ Truesdell, and he left town” (the Chicago area).[3] By the 1870s, he had turned his attention to mining and homeopathy.[45] In 1875, he opened and ran a silver mine while practicing as a homeopathic doctor near Bristol, New Hampshire. The mine failed 10 years later, and he died June 7, 1890, in Bristol.[45]

Some of the other Truesdell bridges also encountered trouble after the Dixon collapse. In May 1875, the western span of the Truesdell bridge at Roscoe fell while 20 head of cattle were on it.[46] In 1877, the Truesdell bridge at Pecatonica was taken down to be replaced by another iron bridge.[47] After the collapse of the Dixon bridge, “The Truesdell truss was largely a discredited design and faded from history,” since it proved to be "untrustworthy and dangerous for all but the smallest spans,” according to a 2012 book about iron bridges in New England.[48]

Engineering analysis

The coroner's jury of May 7 gathered opinions from local citizens only, raising the possibility that their engineering analysis of the bridge was inadequate and incomplete. At the time, the nation's engineering community lacked formal education, and accredited engineering input was not required for public projects like bridges.

Nonetheless, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) had been promoting professionalism in engineers since its beginning in 1852. The collapse of the Dixon bridge in 1873 attracted formal discussion at the ASCE's fifth annual convention, held in Louisville, Ky., on May 21–22, 1873, less than three weeks after the disaster. The association passed a formal resolution: “Resolved: in view of the late calamitous disaster of the falling of the bridge at Dixon, Ill., and other casualties of a similar character …, that a committee be appointed to report at the next Annual Convention the most practicable means of averting such accidents.”[49] The committee's report, “On the Means of Averting Bridge Accidents,” was published three years later, concluding that there were three common causes of bridge failures: (1) Incompetent/corrupt builders, (2) Neglect during construction, and (3) Excessive loads.

The report did not specifically identify the cause of the Dixon collapse. On May 24, 1873, however, the Scientific American published a technical analysis of the Truesdell bridge, concluding, “There is little question but that its theory of construction was wrong and the material poor and clearly inadequate … It has been the opinion of many engineers that the (Truesdell patent) idea is a total failure. Too much light and cast iron is employed, and the lock joint arrangement so weakens the metal that its full strength cannot be gained.”[50]

Unfortunately, bridge collapses continued throughout the 1800s since anyone could work as an engineer without proof of competency, according to the National Society of Professional Engineers. The NSPE says that it wasn’t until 1907 that the first engineering licensure law was enacted (in Wyoming) to protect the public health, safety, and welfare. “Now, every state regulates the practice of engineering to ensure public safety by granting only Professional Engineers (PEs) the authority to sign and seal engineering plans, and offer their services to the public.”[51]

Why so many female fatalities?

The death toll of women was shocking. As the Tribune reported, “The majority of the victims were young girls budding into womanhood; some of them … were factory girls, the sole support of aged mothers.” Yet, the reason for the heavy loss of women's lives was not addressed in the most accounts of the disaster.[3]

Several reports noted that the western sidewalk of the north side of the bridge, the area that proved to be a death trap, was filled with women and children. This may have been due to chivalrous men who graciously gave up these prime viewing spots. For example, as the Dixon Sun reported, P. M. Alexander left his wife on the sidewalk as he moved to the bank “in order to make way for the ladies.”[18] Some newspapers also reported that men and boys abandoned the sidewalk and climbed the 15 foot (4.6 m) truss or watched from the riverbank.[12]

Another fatal element for women may have been the prevailing style of women's dresses at that time. Heavy dresses with hoops and petticoats may have hindered swimming and treading water. Yet, as some reports noted, these dresses had a buoyant effect for younger girls.[14] Whatever the reason, four women perished for every one male fatality.

Rebuilding the bridge

Since the city had spent a large sum for the Truesdell bridge, and the entire investment was now lost (except the five piers in the river), the city council appealed to the county for help in funding a new bridge. In spite of the outpouring of sympathy for the city, the Lee County Board of Supervisors rejected the proposal on May 9. Several newspaper stories noted that the county board included many farmers who disliked the heavy tolls they had to pay for using the Truesdell bridge. The county board also felt that, since the city was the primary beneficiary of the bridge, the city should pay for it. The Sterling newspaper commented, “Correct theory, but not generous action in such a case.”[52]

By June, the Dixon City Council was proceeding with building a temporary wooden bridge to enable continued transportation across the river. On June 4, the Dixon Sun appealed to farmers: “So, good farmers, get ready to come to Dixon, and cross on the new free bridge. Come and see us and shake hands over the differences that have hitherto driven you from Dixon. It is of no use for us to complain at this late hour of the mistake we have made. We made a mistake when we accepted the Truesdell structure. We made another when we made it a toll bridge.”[53]

By June 11, most of the wreckage had been removed.[54] For the new “permanent” bridge, two key issues had to be addressed: toll vs. free and iron vs. wood. Citizens were clearly in favor of a free bridge. (The Truesdell bridge was the last toll bridge in Dixon.) In spite of the intense emotions about the Truesdell Bridge, only two citizens attended the June city council meeting that decided the kind of bridge to be built. Alderman Kelsey proposed that “we build a good wooden bridge, a Howe Truss.” The motion passed unanimously. The overseer of the bridge project promised that the bridge would be “strong enough to carry a train of locomotives.”[55]

In all, 38 bids were received, almost three times the 14 bids received in 1868. On July 23, the Dixon City Council voted 7 to 1 in favor of the $17,795 bid by the American Bridge Company of Chicago.[56] (By comparison, Truesdell's iron bridge cost $30,000.) Work commenced immediately, and the new bridge was finished in November.

References

- ^ Dixon Telegraph, May 1, 1951.

- ^ a b c d e f g “Dixon: Interesting Testimony Before the Coroner’s Jury,” Inter-Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), May 8, 1873.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n “Dixon’s Horror,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1873.

- ^ In 2017, the Dixon bridge at the same location was 713 feet (217 metres) according to Joel Graff, P.E., Illinois Department of Transportation.

- ^ a b “Our Chicago Letter,” Decatur Weekly Republican, June 11, 1868.

- ^ a b “Opening of the New Iron Bridge,” Dixon Weekly Herald, Jan. 27, 1869.

- ^ Assuming that $1 in 1873 = $30 in 2017, the bridge’s cost was in excess of $2 million in 2017 dollars.

- ^ a b c “The Truesdell Bridge,” Belvidere Standard, May 13, 1873.

- ^ “The Dixon Bridge Disaster,” Dixon Telegraph, May 28, 1873.

- ^ “Fall of a Bridge at Elgin, Ill.—Forty Persons Injured,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 14, 1869 (quoting the Chicago Post).

- ^ Semi-Weekly Wisconsin (Milwaukee), July 21, 1869.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Baptism of Death," Dixon Telegraph, May 8, 1873.

- ^ a b c “The Dixon Horror,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 7, 1873.

- ^ a b c “Early Dixonites Recall Bridge Disaster,” Dixon Evening Telegraph, May 4, 1933.

- ^ a b c “Fearful Horror,” Memphis Daily Appeal, May 5, 1873.

- ^ a b c “The Wounded,” Dixon Telegraph, May 15, 1873.

- ^ a b c d “The Dixon Disaster,” Inter-Ocean (Chicago), May 7, 1873.

- ^ a b c d e f Dixon Sun, May 7, 1873.

- ^ a b “Terrible Calamity!” Dixon Telegraph Extra, May 5, 1873.

- ^ Chicago Times, May 6, 1873.

- ^ Bardwell, A.C. (1904). "History of Lee County Illinois". Genealogy Trails. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ a b “The Dixon Disaster,” Inter-Ocean, May 6, 1873.

- ^ Sterling Standard (Sterling, Ill.), May 15, 1873; and Dixon Sun, May 14, 1873.

- ^ “Dixon,” Inter-Ocean, May 9, 1873.

- ^ a b “Dixon’s Woe,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 8, 1873.

- ^ Inter-Ocean, May 8, 1873.

- ^ Some sources say the Baptists lost 12, but 14 are named in “Our Churches,” Dixon Telegraph, May 15, 1873.

- ^ “Dixon,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 12, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Sun Extra, May 4, 1873.

- ^ Memphis Daily Appeal, May 5, 1873.

- ^ Washington (DC) Evening Star, May 5, 1873.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1873.

- ^ Inter-Ocean, May 7, 1873.

- ^ Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 8, 1873.

- ^ (New Orleans) Times-Picayune, May 15, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Telegraph, May 5, 1873.

- ^ New York Times, May 6, 1873.

- ^ “Dixon’s Bridge Disaster Was 56 Years Ago Today,” Sterling Gazette, May 4, 1929.

- ^ "First Baptist Church, Dixon, Lee County IL". Genealogy Trails History Group. February 28, 1976. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ “Mrs. J. H. Pratt Dead,” Dixon Evening Telegraph, Feb. 3, 1893.

- ^ a b Dixon Sun, May 14, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Sun, May 14, 1873; Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1873; Inter-Ocean, May 8, 1873; Dixon Telegraph, May 8, 1873.

- ^ “The Dixon Horror!! Fifty Lives Lost!!” Sterling Standard, May 8, 1873.

- ^ “The Dixon (Ill.) Bridge Disaster: A Letter from Mr. Truesdell—His Explanation and Defense,” New-York Tribune, May 23, 1873.

- ^ a b Richard Watson Musgrove, History of the Town of Bristol, Grafton County, New Hampshire (Bristol, NH: R. W. Musgrove, 1904), p. 446.

- ^ “Neighborhood News,” Belvidere Standard, May 26, 1876.

- ^ Belvidere Standard, Oct. 23, 1877.

- ^ Glenn A. Knoblock, Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2012, pp. 130 and 11.

- ^ D. Van Nostrand, Van Nostrand’s Eclectic Engineering Magazine, Vol. 13 (1875), p. 305.

- ^ “The Falling of the Dixon Bridge,” Scientific American (May 24, 1873), p. 321.

- ^ "100 Years of Engineering Licensure". National Society of Professional Engineers. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Sterling Standard, May 22, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Sun, June 4, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Telegraph, June 11, 1873.

- ^ “Our New Bridge,” Dixon Sun, July 16, 1873.

- ^ Dixon Sun, July 30, 1873.