Digital Visual Interface

| |||

A male DVI-D (single link) connector | |||

| Type | Digital computer video connector | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Production history | |||

| Designer | Digital Display Working Group | ||

| Designed | April 1999 | ||

| Produced | 1999–present | ||

| Superseded | VGA connector | ||

| Superseded by | DisplayPort, HDMI | ||

| General specifications | |||

| Hot pluggable | Yes | ||

| External | Yes | ||

| Video signal |

Digital video stream: Single link: 1920 × 1200 (WUXGA) @ 60 Hz Dual link: 2560 × 1600 (WQXGA) @ 60 Hz Analog video stream: 1920 × 1200 (WUXGA) @ 60 Hz | ||

| Pins |

DVI-D Single Link: 19 DVI-D Dual Link: 25 DVI-I Single Link: 23 DVI-I Dual Link: 29 DVI-A: 11 DVI-M1-DA: 35 | ||

| Data | |||

| Bitrate |

(Single link) 3.96 Gbit/s (Dual link) 7.92 Gbit/s | ||

| Max. devices | 1 | ||

| Protocol | 3 × transition minimized differential signaling data and clock | ||

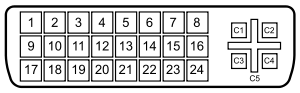

| Pinout | |||

| |||

| A female DVI-I socket from the front | |||

| |||

| Color coded (click to read text) | |||

| Pin 1 | TMDS data 2− | Digital red− (link 1) | |

| Pin 2 | TMDS data 2+ | Digital red+ (link 1) | |

| Pin 3 | TMDS data 2/4 shield | ||

| Pin 4 | TMDS data 4− | Digital green− (link 2) | |

| Pin 5 | TMDS data 4+ | Digital green+ (link 2) | |

| Pin 6 | DDC clock | ||

| Pin 7 | DDC data | ||

| Pin 8 | Analog vertical sync | ||

| Pin 9 | TMDS data 1− | Digital green− (link 1) | |

| Pin 10 | TMDS data 1+ | Digital green+ (link 1) | |

| Pin 11 | TMDS data 1/3 shield | ||

| Pin 12 | TMDS data 3− | Digital blue− (link 2) | |

| Pin 13 | TMDS data 3+ | Digital blue+ (link 2) | |

| Pin 14 | +5 V | Power for monitor when in standby | |

| Pin 15 | Ground | Return for pin 14 and analog sync | |

| Pin 16 | Hot plug detect | ||

| Pin 17 | TMDS data 0− | Digital blue− (link 1) and digital sync | |

| Pin 18 | TMDS data 0+ | Digital blue+ (link 1) and digital sync | |

| Pin 19 | TMDS data 0/5 shield | ||

| Pin 20 | TMDS data 5− | Digital red− (link 2) | |

| Pin 21 | TMDS data 5+ | Digital red+ (link 2) | |

| Pin 22 | TMDS clock shield | ||

| Pin 23 | TMDS clock+ | Digital clock+ (links 1 and 2) | |

| Pin 24 | TMDS clock− | Digital clock− (links 1 and 2) | |

| C1 | Analog red | ||

| C2 | Analog green | ||

| C3 | Analog blue | ||

| C4 | Analog horizontal sync | ||

| C5 | Analog ground | Return for R, G, and B signals | |

Digital Visual Interface (DVI) is a video display interface developed by the Digital Display Working Group (DDWG). The digital interface is used to connect a video source, such as a video display controller, to a display device, such as a computer monitor. It was developed with the intention of creating an industry standard for the transfer of uncompressed digital video content.

DVI devices manufactured as DVI-I have support for analog connections, and are compatible with the analog VGA interface[1] by including VGA pins, while DVI-D devices are digital-only. This compatibility, along with other advantages, led to its widespread acceptance over competing digital display standards Plug and Display (P&D) and Digital Flat Panel (DFP).[2] Although DVI is predominantly associated with computers, it is sometimes used in other consumer electronics such as television sets and DVD players.

History

An earlier attempt to promulgate an updated standard to the analog VGA connector was made by the Video Electronics Standards Association (VESA) in 1994 and 1995, with the Enhanced Video Connector (EVC), which was intended to consolidate cables between the computer and monitor.[3][4] EVC used a 35-pin Molex MicroCross connector and carried analog video (input and output), analog stereo audio (input and output), and data (via USB and FireWire). At the same time, with the increasing availability of digital flat-panel displays, the priority shifted to digital video transmission, which would remove the extra analog/digital conversion steps required for VGA and EVC;[5]: 5–6 the EVC connector was reused by VESA,[6] which released the Plug & Display (P&D) standard in 1997.[3] P&D offered single-link TMDS digital video with, as an option, analog video output and data (USB and FireWire), using a 35-pin MicroCross connector similar to EVC; the analog audio and video input lines from EVC were repurposed to carry digital video for P&D.[5]: 4 [7]: §1.3.3

Because P&D was a physically large, expensive connector, a consortium of companies developed the DFP standard (1999), which was focused solely on digital video transmission using a 20-pin micro ribbon connector and omitted the analog video and data capabilities of P&D.[4]: 3 [5]: 4 DVI instead chose to strip just the data functions from P&D, using a 29-pin MicroCross connector to carry digital and analog video.[8] Critically, DVI allows dual-link TMDS signals,[9] meaning it supports higher resolutions than the single-link P&D and DFP connectors, which led to its successful adoption as an industry standard. Compatibility of DVI with P&D and DFP is accomplished typically through passive adapters that provide appropriate physical interfaces, as all three standards use the same DDC/EDID handshaking protocols and TMDS digital video signals.[10]: §1.3.7

DVI made its way into products starting in 1999. One of the first DVI monitors was Apple's original Cinema Display, which launched in 1999.

Technical overview

DVI's digital video transmission format is based on panelLink, a serial format developed by Silicon Image that utilizes a high-speed serial link called transition minimized differential signaling (TMDS).

TMDS

Digital video pixel data is transported using multiple TMDS twisted pairs. At the electrical level, these pairs are highly resistant to electrical noise and other forms of analog distortion.

Single link

A single link DVI connection has four TMDS pairs. Three data pairs carry their designated 8-bit RGB component (red, green, or blue) of the video signal for a total of 24 bits per pixel. The fourth pair carries the TMDS clock. The binary data is encoded using 8b/10b encoding. DVI does not use packetization, but rather transmits the pixel data as if it were a rasterized analog video signal. As such, the complete frame is drawn during each vertical refresh period. The full active area of each frame is always transmitted without compression. Video modes typically use horizontal and vertical refresh timings that are compatible with cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays, though this is not a requirement. In single link mode, the maximum TMDS clock frequency is 165 MHz, which supports a maximum resolution of 2.75 megapixels (including blanking interval) at 60 Hz refresh. For practical purposes, this allows a maximum 16:10 screen resolution of 1920 × 1200 at 60 Hz.

Dual link

To support higher-resolution display devices, the DVI specification contains a provision for dual link. Dual link DVI doubles the number of TMDS data pairs, effectively doubling the video bandwidth, which allows higher resolutions up to 2560 × 1600 at 60 Hz or higher refresh rates for lower resolutions.

Compatibility

For backward compatibility with displays using analog VGA signals, some of the contacts in the DVI connector carry the analog VGA signals.

To ensure a basic level of interoperability, DVI compliant devices are required to support one baseline display mode, "low pixel format" (640 × 480 at 60 Hz).

DDC

Like modern analog VGA connectors, the DVI connector includes pins for the display data channel (DDC), which allows the graphics adapter to read the monitor's extended display identification data (EDID). When a source and display using the DDC2 revision are connected, the source first queries the display's capabilities by reading the monitor EDID block over an I²C link. The EDID block contains the display's identification, color characteristics (such as gamma value), and table of supported video modes. The table can designate a preferred mode or native resolution. Each mode is a set of timing values that define the duration and frequency of the horizontal/vertical sync, the positioning of the active display area, the horizontal resolution, vertical resolution, and refresh rate.

Cable length

The maximum length recommended for DVI cables is not included in the specification, since it is dependent on the TMDS clock frequency. In general, cable lengths up to 4.5 metres (15 ft) will work for display resolutions up to 1920 × 1200. Longer cables up to 15 metres (49 ft) in length can be used with display resolutions 1280 × 1024 or lower. For greater distances, the use of a DVI booster—a signal repeater which may use an external power supply—is recommended to help mitigate signal degradation.

Connector

The DVI connector on a device is given one of three names, depending on which signals it implements:

- DVI-I (integrated, combines digital and analog in the same connector; digital may be single or dual link)

- DVI-D (digital only, single link or dual link)

- DVI-A (analog only)

Most DVI connector types—the exception is DVI-A—have pins that pass digital video signals. These come in two varieties: single link and dual link. Single link DVI employs a single transmitter with a TMDS clock up to 165 MHz that supports resolutions up to 1920 × 1200 at 60 Hz. Dual link DVI adds six pins, at the center of the connector, for a second transmitter increasing the bandwidth and supporting resolutions up to 2560 × 1600 at 60 Hz.[11] A connector with these additional pins is sometimes referred to as DVI-DL (dual link). Dual link should not be confused with dual display (also known as dual head), which is a configuration consisting of a single computer connected to two monitors, sometimes using a DMS-59 connector for two single link DVI connections.

In addition to digital, some DVI connectors also have pins that pass an analog signal, which can be used to connect an analog monitor. The analog pins are the four that surround the flat blade on a DVI-I or DVI-A connector. A VGA monitor, for example, can be connected to a video source with DVI-I through the use of a passive adapter. Since the analog pins are directly compatible with VGA signaling, passive adapters are simple and cheap to produce, providing a cost-effective solution to support VGA on DVI. The long flat pin on a DVI-I connector is wider than the same pin on a DVI-D connector, so even if the four analog pins were manually removed, it still wouldn't be possible to connect a male DVI-I to a female DVI-D. It is possible, however, to join a male DVI-D connector with a female DVI-I connector.[12]

DVI is the only widespread video standard that includes analog and digital transmission in the same connector.[13] Competing standards are exclusively digital: these include a system using low-voltage differential signaling (LVDS), known by its proprietary names FPD-Link (flat-panel display) and FLATLINK; and its successors, the LVDS Display Interface (LDI) and OpenLDI.

Some DVD players, HDTV sets, and video projectors have DVI connectors that transmit an encrypted signal for copy protection using the High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection (HDCP) protocol. Computers can be connected to HDTV sets over DVI, but the graphics card must support HDCP to play content protected by digital rights management (DRM).

Specifications

Digital

- Minimum TMDS clock frequency: 25.175 MHz

- Used for the mandatory "low pixel format" display mode: VGA (640x480) @ 60 Hz

- Maximum single link TMDS clock frequency: 165 MHz

- Single link maximum gross bit rate (including 8b/10b overhead): 4.95 Gbit/s

- Net bit rate (subtracting 8b/10b overhead): 3.96 Gbit/s

- Dual link bit rates are twice that of single link at an identical clock frequency.

- Gross bit rate (Including 8b/10b overhead) at a 165 MHz clock: 9.90 Gbit/s.

- Net bit rate (subtracting 8b/10b overhead): 7.92 Gbit/s

- Clocks above 165 MHz are allowed in dual link mode[note 1]

- Gross bit rate (Including 8b/10b overhead) at a 165 MHz clock: 9.90 Gbit/s.

- Bits per pixel:

- 24 bits per pixel support is mandatory in all resolutions supported.

- Less than 24 bits per pixel is optional.

- Dual link optionally supports up to 48 bits per pixel.

- If a depth greater than 24 bits per pixel is desired, the least significant bits are sent on the second link.

- Pixels per TMDS clock cycle:

- 1 (single link at 24 bits or less per pixel, and dual link for 25 to 48 bits per pixel) or

- 2 (dual link at 24 bits or less per pixel)

- Example display modes (single link):

- SXGA (1280 × 1024) @ 85 Hz with GTF blanking (159 MHz TMDS clock)

- FHD (1920 × 1080) @ 60 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (139 MHz TMDS clock)

- UXGA (1600 × 1200) @ 60 Hz with GTF blanking (161 MHz TMDS clock)

- WUXGA (1920 × 1200) @ 60 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (154 MHz TMDS clock)

- WQXGA (2560 × 1600) @ 30 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (132 MHz TMDS clock)

- Example display modes (dual link):

- QXGA (2048 × 1536) @ 72 Hz with CVT blanking (2 pixels per 163 MHz TMDS clock)

- FHD (1920 × 1080) @ 144 Hz[14]

- WUXGA (1920 × 1200) @ 120 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (2 pixels per 154 MHz TMDS clock)

- WQXGA (2560 × 1600) @ 60 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (2 pixels per 135 MHz TMDS clock)

- WQUXGA (3840 × 2400) @ 30 Hz with CVT-RB blanking (2 pixels per 146 MHz TMDS clock)

Generalized Timing Formula (GTF) is a VESA standard which can easily be calculated with the Linux gtf utility. Coordinated Video Timings-Reduced Blanking (CVT-RB) is a VESA standard which offers reduced horizontal and vertical blanking for non-CRT based displays.[15]

Digital data encoding

One of the purposes of DVI stream encoding is to provide a DC-balanced output that reduces decoding errors. This goal is achieved by using 10-bit symbols for 8-bit or less characters and using the extra bits for the DC balancing.

Like other ways of transmitting video, there are two different regions: the active region, where pixel data is sent, and the control region, where synchronization signals are sent. The active region is encoded using transition-minimized differential signaling, where the control region is encoded with a fixed 8b/10b encoding. As the two schemes yield different 10-bit symbols, a receiver can fully differentiate between active and control regions.

When DVI was designed, most computer monitors were still of the cathode-ray tube type that require analog video synchronization signals. The timing of the digital synchronization signals matches the equivalent analog ones, so the process of transforming DVI to and from an analog signal does not require extra (high-speed) memory, expensive at the time.

HDCP is an extra layer that transforms the 10-bit symbols before transmitting. Only after correct authorization can the receiver undo the HDCP encryption. Control regions are not encrypted in order to let the receiver know when the active region starts.

Clock and data relationship

DVI provide one TMDS clock pair and 3 TMDS data pairs in single link mode or 6 TMDS data pairs in dual link mode. TMDS data pairs operate at a gross bit rate that is 10 times the frequency of the TMDS clock. In each TMDS clock period there is a 10-bit symbol per TMDS data pair representing 8-bits of pixel color. In single link mode each set of three 10-bit symbols represents one 24-bit pixel, while in dual link mode each set of six 10-bit symbols either represents two 24-bit pixels or one pixel of up to 48-bit color depth.

The specification document allows the data and the clock to not be aligned. However, as the ratio between the TMDS clock and gross bit rate per TMDS pair is fixed at 1:10, the unknown alignment is kept over time. The receiver must recover the bits on the stream using any of the techniques of clock/data recovery to find the correct symbol boundary. The DVI specification allows the TMDS clock to vary between 25 MHz and 165 MHz. This 1:6.6 ratio can make clock recovery difficult, as phase-locked loops, if used, need to work over a large frequency range. One benefit of DVI over other interfaces is that it is relatively straightforward to transform the signal from the digital domain into the analog domain using a video DAC, as both clock and synchronization signals are transmitted. Fixed frequency interfaces, like DisplayPort, need to reconstruct the clock from the transmitted data.

Display power management

The DVI specification includes signaling for reducing power consumption. Similar to the analog VESA display power management signaling (DPMS) standard, a connected device can turn a monitor off when the connected device is powered down, or programmatically if the display controller of the device supports it. Devices with this capability can also attain Energy Star certification.

Analog

The analog section of the DVI specification document is brief and points to other specifications like VESA VSIS[16] for electrical characteristics and GTFS for timing information. The motivation for including analog is to keep compatibility with the previous VGA cables and connectors. VGA pins for HSync, Vsync and three video channels are available in both DVI-I or DVI-A (but not DVI-D) connectors and are electrically compatible, while pins for DDC (clock and data) and 5 V power and ground are kept in all DVI connectors. Thus, a passive adapter can interface between DVI-I or DVI-A (but not DVI-D) and VGA connectors.

DVI and HDMI compatibility

HDMI is a newer digital audio/video interface developed and promoted by the consumer electronics industry. DVI and HDMI have the same electrical specifications for their TMDS and VESA/DDC twisted pairs. However HDMI and DVI differ in several key ways.

- HDMI lacks VGA compatibility and does not include analog signals.

- DVI is limited to the RGB color model while HDMI also supports YCbCr 4:4:4 and YCbCr 4:2:2 color spaces, which are generally not used for computer graphics.

- In addition to digital video, HDMI supports the transport of packets used for digital audio.

- HDMI sources differentiate between legacy DVI displays and HDMI-capable displays by reading the display's EDID block.

To promote interoperability between DVI-D and HDMI devices, HDMI source components and displays support DVI-D signaling. For example, an HDMI display can be driven by a DVI-D source because HDMI and DVI-D both define an overlapping minimum set of supported resolutions and frame buffer formats.

Some DVI-D sources use non-standard extensions to output HDMI signals including audio (e.g. ATI 3000-series and NVIDIA GTX 200-series).[17] Some multimedia displays use a DVI to HDMI adapter to input the HDMI signal with audio. Exact capabilities vary by video card specifications.

In the reverse scenario, a DVI display that lacks optional support for HDCP might be unable to display protected content even though it is otherwise compatible with the HDMI source. Features specific to HDMI such as remote control, audio transport, xvYCC and deep color are not usable in devices that support only DVI signals. HDCP compatibility between source and destination devices is subject to manufacturer specifications for each device.

Proposed successors

- IEEE 1394 was proposed by High-Definition Audio-Video Network Alliance (HANA Alliance) for all cabling needs, including video, over coaxial or 1394 cable as a combined data stream. However, this interface does not have enough throughput to handle uncompressed HD video, so it is unsuitable for applications such as video games and interactive program guides.

- High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI), a forward-compatible standard that also includes digital audio transmission

- Unified Display Interface (UDI) was proposed by Intel to replace both DVI and HDMI, but was deprecated in favor of DisplayPort.

- DisplayPort (a license-free standard proposed by VESA to succeed DVI that has optional DRM mechanisms) / Mini DisplayPort

- Thunderbolt: an interface that uses the USB-C connector (from Thunderbolt 3 and onward; the Mini DisplayPort connector was used for Thunderbolt 1 and 2) but combines PCI Express (PCIe) and DisplayPort (DP) into one serial signal, permitting the connection of PCIe devices in addition to video displays. It provides DC power as well.

In December 2010, Intel, AMD, and several computer and display manufacturers announced they would stop supporting DVI-I, VGA and LVDS-technologies from 2013/2015, and instead speed up adoption of DisplayPort and HDMI.[18][19] They also stated: "Legacy interfaces such as VGA, DVI and LVDS have not kept pace, and newer standards such as DisplayPort and HDMI clearly provide the best connectivity options moving forward. In our opinion, DisplayPort 1.2 is the future interface for PC monitors, along with HDMI 1.4a for TV connectivity".

See also

- DMS-59 – a single DVI sized connector providing two single link DVI or VGA channels

- List of video connectors

- DiiVA

- Lightning (connector)

Notes

References

- ^ "Digital Visual Interface adoption accelerates as industry prepares for next wave of DVI-compliant products". DDWG, copy preserved by Internet Archive. February 16, 2000. Archived from the original on 28 August 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Eiden, Hermann (July 7, 1999). "TFT Guide Part 3 - Digital Interfaces". TomsHardware.com. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ a b "VESA Standards". Video Electronics Standards Association. Archived from the original on January 17, 1999.

- ^ a b Manchester, Gary (1999). The VESA Digital Flat Panel (DFP) Standard: A White Paper (PDF) (Report). VESA Marketing Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c Digital Visual Interface & TMDS Extensions (PDF) (Report). Silicon Image. October 2004. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Manchester, Gary (October 7, 1996). "Molex PnD intellectual property letter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2003.

- ^ "VESA Plug and Display (P&D) Standard, Version 1" (PDF). Video Electronics Standards Association. June 11, 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2003.

- ^ "MicroCross DVI Connector System: Digital Visual Interface Standard" (PDF). Molex. December 2000. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "MicroCross DVI (Digital Visual Interface) Connector System" (PDF). Molex. November 1999. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Digital Visual Interface Revision 1.0" (PDF). Digital Display Working Group. 2 April 1999. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Walton, Jarred (March 2, 2007). "Dell 2407WFP and 3007WFP LCD Comparison". AnandTech. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Docter, Quentin; Dulaney, Emmett; Skandier, Toby (2012). CompTIA A+ Complete Deluxe Study Guide: Exams 220-801 and 220-802. Indianapolis, Indiana: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1118324066.

- ^ Kruegle, Herman (2006). "8". CCTV Surveillance: Analog and Digital Video Practices And Technology. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 268. ISBN 0-7506-7768-6.

- ^ "The Best DVI Cable for 144hz | The Technology Land". thetechnologyland.com. 2019-08-21. Retrieved 2022-07-14.

- ^ "Advanced Timing and CEA/EIA-861B Timings". NVIDIA. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ Video Signal Standard (VSIS) Version 1, Rev. 2, available for purchuase at http://www.vesa.org/

- ^ "HDMI Specification 1.3a Appendix C" (PDF). HDMI Licensing, LLC. 2006-11-10. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ Intel Newsrom – Leading PC Companies Move to All Digital Display Technology, Phasing out Analog (8. December 2010)

- ^ "HDMI versions". 2017-01-17. Wednesday, 1 February 2017

Further reading

- Silicon Image; Molex (1999-04-02). "Digital Visual Interface" (PDF). Revision 1.0: Initial Specification Release. Digital Display Working Group. Archived from the original on 2012-08-13.