Diffusion damping

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

In modern cosmological theory, diffusion damping, also called photon diffusion damping, is a physical process which reduced density inequalities (anisotropies) in the early universe, making the universe itself and the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) more uniform. Around 300,000 years after the Big Bang, during the epoch of recombination, diffusing photons travelled from hot regions of space to cold ones, equalising the temperatures of these regions. This effect is responsible, along with baryon acoustic oscillations, the Doppler effect, and the effects of gravity on electromagnetic radiation, for the eventual formation of galaxies and galaxy clusters, these being the dominant large scale structures which are observed in the universe. It is a damping by diffusion, not of diffusion.[1]

The strength of diffusion damping is calculated by a mathematical expression for the damping factor, which figures into the Boltzmann equation, an equation which describes the amplitude of perturbations in the CMB.[2] The strength of the diffusion damping is chiefly governed by the distance photons travel before being scattered (diffusion length). The primary effects on the diffusion length are from the properties of the plasma in question: different sorts of plasma may experience different sorts of diffusion damping. The evolution of a plasma may also affect the damping process.[3] The scale on which diffusion damping works is called the Silk scale and its value corresponds to the size of galaxies of the present day. The mass contained within the Silk scale is called the Silk mass and it corresponds to the mass of the galaxies.[4]

Introduction

Diffusion damping took place about 13.8 billion years ago,[6] during the stage of the early universe called recombination or matter-radiation decoupling. This period occurred about 320,000 years after the Big Bang.[7] This is equivalent to a redshift of around z = 1090.[8] Recombination was the stage during which simple atoms, e.g. hydrogen and helium, began to form in the cooling, but still very hot, soup of protons, electrons and photons that composed the universe. Prior to the recombination epoch, this soup, a plasma, was largely opaque to the electromagnetic radiation of photons. This meant that the permanently excited photons were scattered by the protons and electrons too often to travel very far in straight lines.[9] During the recombination epoch, the universe cooled rapidly as free electrons were captured by atomic nuclei; atoms formed from their constituent parts and the universe became transparent: the amount of photon scattering decreased dramatically. Scattering less, photons could diffuse (travel) much greater distances.[1][10] There was no significant diffusion damping for electrons, which could not diffuse nearly as far as photons could in similar circumstances. Thus all damping by electron diffusion is negligible when compared to photon diffusion damping.[11]

Acoustic perturbations of initial density fluctuations in the universe made some regions of space hotter and denser than others.[12] These differences in temperature and density are called anisotropies. Photons diffused from the hot, overdense regions of plasma to the cold, underdense ones: they dragged along the protons and electrons: the photons pushed electrons along, and these, in turn, pulled on protons by the Coulomb force. This caused the temperatures and densities of the hot and cold regions to be averaged and the universe became less anisotropic (characteristically various) and more isotropic (characteristically uniform). This reduction in anisotropy is the damping of diffusion damping. Diffusion damping thus damps temperature and density anisotropies in the early universe. With baryonic matter (protons and electrons) escaping the dense areas along with the photons; the temperature and density inequalities were adiabatically damped. That is to say the ratios of photons to baryons remained constant during the damping process.[3][13][14][15][16]

Photon diffusion was first described in Joseph Silk's 1968 paper entitled "Cosmic Black-Body Radiation and Galaxy Formation",[17] which was published in The Astrophysical Journal. As such, diffusion damping is sometimes also called Silk damping,[5] though this term may apply only to one possible damping scenario.[11][18][19] Silk damping was thus named after its discoverer.[4][19][20]

Magnitude

The magnitude of diffusion damping is calculated as a damping factor or suppression factor, represented by the symbol , which figures into the Boltzmann equation, an equation which describes the amplitude of perturbations in the CMB.[2] The strength of the diffusion damping is chiefly governed by the distance photons travel before being scattered (diffusion length). What affect the diffusion length are primarily the properties of the plasma in question: different sorts of plasma may experience different sorts of diffusion damping. The evolution of a plasma may also affect the damping process.[3]

Where:

- is the conformal time.

- is the visibility function, giving the probability that a CMB photon observed today last scattered at a conformal time . The quantity is the optical depth to Thomson scattering in the plasma, which is roughly the integrated number of scatterings undergone by a given photon.

- is the wave number of the wave being suppressed.[21]

- is the exponential damping envelope due to diffusion.

The damping factor , when factored into the Boltzmann equation for the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB), reduces the amplitude of perturbations:

- is the conformal time at decoupling.

- is the "monopole [perturbation] of the photon distribution function"[2]

- is a "gravitational-potential [perturbation] in the Newtonian gauge". The Newtonian gauge is a quantity with importance in the General Theory of Relativity.[2]

- is the effective temperature.

Mathematical calculations of the damping factor depend on , or the effective diffusion scale, which in turn depends on a crucial value, the diffusion length, .[23] The diffusion length relates how far photons travel during diffusion, and comprises a finite number of short steps in random directions. The average of these steps is the Compton mean free path, and is denoted by . As the direction of these steps are randomly taken, is approximately equal to , where is the number of steps the photon takes before the conformal time at decoupling ().[3]

The diffusion length increases at recombination because the mean free path does, with less photon scattering occurring; this increases the amount of diffusion and damping. The mean free path increases because the electron ionisation fraction, , decreases as ionised hydrogen and helium bind with the free, charged electrons. As this occurs, the mean free path increases proportionally: . That is, the mean free path of the photons is inversely proportional to the electron ionisation fraction and the baryon number density (). That means that the more baryons there were, and the more they were ionised, the shorter the average photon could travel before encountering one and being scattered.[3] Small changes to these values before or during recombination can augment the damping effect considerably.[3] This dependence on the baryon density by photon diffusion allows scientists to use analysis of the latter to investigate the former, in addition to the history of ionisation.[23]

The effect of diffusion damping is greatly augmented by the finite width of the surface of last scattering (SLS).[24] The finite width of the SLS means the CMB photons we see were not all emitted at the same time, and the fluctuations we see are not all in phase.[25] It also means that during recombination, the diffusion length changed dramatically, as the ionisation fraction shifted.[26]

Model dependence

In general, diffusion damping produces its effects independent of the cosmological model being studied, thereby masking the effects of other, model-dependent phenomena. This means that without an accurate model of diffusion damping, scientists cannot judge the relative merits of cosmological models, whose theoretical predictions cannot be compared with observational data, this data being obscured by damping effects. For example, the peaks in the power spectrum due to acoustic oscillations are decreased in amplitude by diffusion damping. This deamplification of the power spectrum hides features of the curve, features that would otherwise be more visible.[27][28]

Though general diffusion damping can damp perturbations in collisionless dark matter simply due to photon dispersion, the term Silk damping applies only to damping of adiabatic models of baryonic matter, which is coupled to the diffusing photons, not dark matter,[11] and diffuses with them.[18][19] Silk damping is not as significant in models of cosmological development which posit early isocurvature fluctuations (i.e. fluctuations which do not require a constant ratio of baryons and photons). In this case, increases in baryon density do not require corresponding increases in photon density, and the lower the photon density, the less diffusion there would be: the less diffusion, the less damping.[16] Photon diffusion is not dependent on the causes of the initial fluctuations in the density of the universe.[23]

Effects

Speed

Damping occurs at two different scales, with the process working more quickly over short ranges than over longer distances. Here, a short length is one that is lower than the mean free path of the photons. A long distance is one that is greater than the mean free path, if still less than the diffusion length. On the smaller scale, perturbations are damped almost instantaneously. On the larger scale, anisotropies are decreased more slowly, with significant degradation happening within one unit of Hubble time.[11]

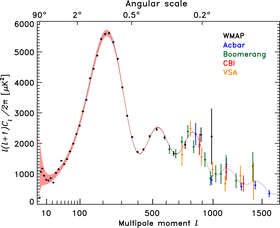

The Silk scale and the Silk mass

Diffusion damping exponentially decreases anisotropies in the CMB on a scale (the Silk scale)[4] much smaller than a degree, or smaller than approximately 3 megaparsecs.[5] This angular scale corresponds to a multipole moment .[15][29] The mass contained within the Silk scale is the silk mass. Numerical evaluations of the Silk mass yield results on the order of solar masses at recombination[30] and on the order of the mass of a present-day galaxy or galaxy cluster in the current era.[4][11]

Scientists say diffusion damping affects small angles and corresponding anisotropies. Other effects operate on a scale called intermediate or large . Searches for anisotropies on a small scale are not as difficult as those on larger scales, partly because they may employ ground-based telescopes and their results can be more easily predicted by current theoretical models.[31]

Galaxy formation

Scientists study photon diffusion damping (and CMB anisotropies in general) because of the insight the subject provides into the question, "How did the universe come to be?". Specifically, primordial anisotropies in the temperature and density of the universe are supposed to be the causes of later large-scale structure formation. Thus it was the amplification of small perturbations in the pre-recombination universe that grew into the galaxies and galaxy clusters of the present era. Diffusion damping made the universe isotropic within distances on the order of the Silk Scale. That this scale corresponds to the size of observed galaxies (when the passage of time is taken into account) implies that diffusion damping is responsible for limiting the size of these galaxies. The theory is that clumps of matter in the early universe became the galaxies that we see today, and the size of these galaxies is related to the temperature and density of the clumps.[32][33]

Diffusion may also have had a significant effect on the evolution of primordial cosmic magnetic fields, fields which may have been amplified over time to become galactic magnetic fields. However, these cosmic magnetic fields may have been damped by radiative diffusion: just as acoustic oscillations in the plasma were damped by the diffusion of photons, so were magnetosonic waves (waves of ions travelling through a magnetised plasma). This process began before the era of neutrino decoupling and ended at the time of recombination.[30][34]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b Hu, Sugiyama & Silk (1996-04-28), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g Jungman, Kamionkowski, Kosowsky & Spergel (1995-12-20), p. 2–4

- ^ a b c d e f Hu (1995-08-26), p. 12–13

- ^ a b c d Madsen (1996-05-15), p. 99–101

- ^ a b c Bonometto, Gorini & Moschella (2001-12-15), p. 227–8

- ^ "Cosmic Detectives". The European Space Agency (ESA). 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ^ "Simple but challenging: The Universe according to Planck". The European Space Agency (ESA). 2013-03-21. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ^ Ade, P. A. R.; Aghanim, N.; Armitage-Caplan, C.; et al. (Planck Collaboration) (22 March 2013). "Planck 2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 571: A16. arXiv:1303.5076. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A..16P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591. S2CID 118349591.

- ^ Hu (1995-08-26), p. 6

- ^ Liddle & Lyth (2000-04-13), p. 63, 120

- ^ a b c d e Padmanabhan (1993-06-25), p. 171–2

- ^ Harrison (1970-05-15)

- ^ Madsen (1996-05-15), p. 99–100

- ^ Longair (2008-01-08), p. 355

- ^ a b Jetzer & Pretzl (2002-07-31), p. 6

- ^ a b Rich (2001-06-15), p. 256

- ^ Silk (1968-02-01)

- ^ a b Partridge (1995-09-29), p. 302

- ^ a b c Bonometto, Gorini & Moschella (2001-12-15), p. 55

- ^ Hu (1994-06-28), p. 15

- ^ Longair (2008-01-08), p. 450

- ^ Hu (1995-08-26), p. 146

- ^ a b c Hu, Sugiyama & Silk (1996-04-28), p. 5

- ^ (1995-08-26), p. 137

- ^ Durrer (2001-09-17), p. 5

- ^ Hu (1995-08-26), pp. 156–7

- ^ Hu (1995-08-26), p. 136–8

- ^ Hu & White (1997-04-20), p. 568–9

- ^ Papantonopoulos (2005-03-24), p. 63

- ^ a b Jedamzik, Katalinić & Olinto (1996-06-13), p. 1–2

- ^ Kaiser & Silk (1986-12-11), p. 533

- ^ Hu & Sugiyama (1994-07-28), p. 2

- ^ Sunyaev & Zel'dovich (Sept. 1980), p. 1

- ^ Brandenburg, Enqvist & Olesen (January 1997), p. 2

Bibliography

- Brandenburg, Axel; Kari Enqvist; Poul Olesen (January 1997). "The effect of Silk damping on primordial magnetic fields". Physics Letters B. 392 (3–4): 395–402. arXiv:hep-ph/9608422. Bibcode:1997PhLB..392..395B. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(96)01566-3. S2CID 14213997.

- Bonometto, S.; V. Gorini; U. Moschella (2001-12-15). Modern Cosmology (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-7503-0810-6.

- Durrer, Ruth (2001-09-17). "Physics of Cosmic Microwave Background anisotropies and primordial fluctuations". Space Science Reviews. 100: 3–14. arXiv:astro-ph/0109274. Bibcode:2002SSRv..100....3D. doi:10.1023/A:1015822607090. S2CID 4694878.

- Harrison, E. R. (1970-05-15). "Fluctuations at the Threshold of Classical Cosmology". Physical Review D. 1 (10): 2726–2730. Bibcode:1970PhRvD...1.2726H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.1.2726.

- Hu, Wayne (1994-06-28). "The Nature versus Nurture of Anisotropies". CMB Anisotropies Two Years After Cobe: Observations. p. 188. arXiv:astro-ph/9406071. Bibcode:1994caty.conf..188H.

- Hu, Wayne (1995-08-26). "Wandering in the Background: A CMB Explorer". arXiv:astro-ph/9508126.

- Hu, Wayne; Naoshi Sugiyama (1995). "Anisotropies in the Cosmic Microwave Background: An Analytic Approach". The Astrophysical Journal (Submitted manuscript). 444: 489–506. arXiv:astro-ph/9407093. Bibcode:1995ApJ...444..489H. doi:10.1086/175624. S2CID 14452520.

- Hu, Wayne; Naoshi Sugiyama; Joseph Silk (1997). "The Physics of Microwave Background Anisotropies". Nature. 386 (6620): 37–43. arXiv:astro-ph/9604166. Bibcode:1997Natur.386...37H. doi:10.1038/386037a0. S2CID 4243435.

- Hu, Wayne; Martin White (1997). "The Damping Tail of Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropies". The Astrophysical Journal. 479 (2): 568–579. arXiv:astro-ph/9609079. Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..568H. doi:10.1086/303928. S2CID 14601866.

- Jedamzik, K.; V. Katalinić; A. Olinto (1996-06-13). "Damping of Cosmic Magnetic Fields". Physical Review D. 57 (6): 3264–3284. arXiv:astro-ph/9606080. Bibcode:1998PhRvD..57.3264J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.57.3264. S2CID 44245671.

- Jetzer, Ph.; K. Pretzl (2002-07-31). Rudolf von Steiger (ed.). Matter in the Universe. Space Sciences Series of ISSI. Springer. pp. 328. ISBN 978-1-4020-0666-1.

- Jungman, Gerard; Marc Kamionkowski; Arthur Kosowsky; David N Spergel (1995-12-20). "Cosmological-Parameter Determination with Microwave Background Maps". Physical Review D. 54 (2): 1332–1344. arXiv:astro-ph/9512139. Bibcode:1996PhRvD..54.1332J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.54.1332. PMID 10020810. S2CID 31586019.

- Kaiser, Nick; Joseph Silk (1986-12-11). "Cosmic microwave background anisotropy". Nature. 324 (6097): 529–537. Bibcode:1986Natur.324..529K. doi:10.1038/324529a0. PMID 29517722. S2CID 3819136.

- Liddle, Andrew R.; David Hilary Lyth (2000-04-13). Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure. Cambridge University Press. pp. 400. ISBN 978-0-521-57598-0.

- Longair, Malcolm S. (2008-01-08). Galaxy Formation (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 738. ISBN 978-3-540-73477-2.

- Madsen, Mark S. (1996-05-15). Dynamic Cosmos (1st ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-412-62300-4.

- Partridge, R. B. (1995-09-29). 3K: The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. Cambridge University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-521-35254-3.

- Padmanabhan, T. (1993-06-25). Structure Formation in the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-521-42486-8.

- Rich, James (2001-06-15). Fundamentals of Cosmology (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 302. ISBN 978-3-540-41350-9.

- Ryden, Barbara (2002-11-12). Introduction to Cosmology. Addison Wesley. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-8053-8912-8.

- Silk, Joseph (1968-02-01). "Cosmic Black-Body Radiation and Galaxy Formation". Astrophysical Journal. 151: 459. Bibcode:1968ApJ...151..459S. doi:10.1086/149449.

- Papantonopoulos, E. (2005-03-24). The Physics of the Early Universe (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 300. ISBN 978-3-540-22712-0.

- Sunyaev, R. A.; Y. B. Zel'dovich (Sep 1980). "Microwave background radiation as a probe of the contemporary structure and history of the universe". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 18 (1): 537–560. Bibcode:1980ARA&A..18..537S. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.18.090180.002541.

External links

![{\displaystyle {\mathcal {D}}({\mathit {k}})=\int _{0}^{\eta _{0}}\left({\dot {\tau }}e^{-\tau }\right)e^{-[{\mathit {k}}/{{\mathit {k}}_{\mathit {D}}(\eta )}]^{2}}\;d\eta .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0b85e403a4140420fcdb60f0b76734bf9193269b)

![{\displaystyle e^{-[{\mathit {k}}/{{\mathit {k}}_{\mathit {D}}(\eta )}]^{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/446e222df49cb0f83028262165f2c761e0fbb47b)

=[{\hat {\Theta }}_{0}+\Psi ](\eta _{\ast }){\mathcal {D}}({\mathit {k}}).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efdb1e88d42412b4557cbaee57d95792e6d88f94)

}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d9e46298953c99e88cce22b43b3ccf95955492a)