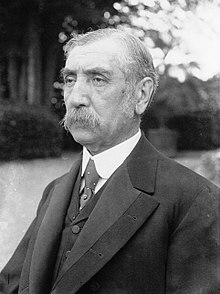

Damat Ferid Pasha

Mehmed Adil Ferid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office 4 March 1919 – 2 October 1919 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed VI |

| Preceded by | Ahmet Tevfik Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ali Rıza Pasha |

| In office 5 April 1920 – 21 October 1920 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed VI |

| Preceded by | Salih Hulusi Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Ahmet Tevfik Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1853 Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 6 October 1923 (aged 69–70) Nice, France |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Political party | Freedom and Accord Party |

| Spouse | Mediha Sultan |

Damat Mehmed Adil Ferid Pasha (Ottoman Turkish: محمد عادل فريد پاشا Turkish: Damat Ferit Paşa; 1853 – 6 October 1923), known simply as Damat Ferid Pasha, was an Ottoman liberal statesman, who held the office of Grand Vizier, the de facto prime minister of the Ottoman Empire, during two periods under the reign of the last Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI, the first time between 4 March 1919 and 2 October 1919 and the second time between 5 April 1920 and 21 October 1920. Officially, he was brought to the office a total of five times, since his cabinets were recurrently dismissed under various pressures and he had to present new ones.[1] Because of his involvement in the Treaty of Sèvres, his collaboration with the occupying Allied powers, and his readiness to acknowledge atrocities against the Armenians, he was declared a traitor and subsequently a persona non grata in Turkey. He emigrated to Europe at the end of the Greco-Turkish War.

Early life and career

Some claim that Mehmed Adil Ferid was born in 1853 in Constantinople as the son of Izet Efendi, who was born in Potoci near Taşlıca (now Pljevlja, Montenegro). He was a member of the Ottoman Council of State (Şûrâ-yı Devlet) and Governor of Beirut and Sidon in 1857, but there is no clear evidence about this information.[citation needed]

In 1879, Ferid was enrolled at the Schools of Islamic charities in Sidon. He served several positions in Ottoman administration before he entered the foreign office of the Ottoman Empire and was assigned to different posts at embassies in Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and London.

He married a daughter of Abdülmecid I, Mediha Sultan, which earned him the title of "damat" ("bridegroom" to the Ottoman dynasty). Like his father, he became a member of the Council of State in 1884 and earned the title of vizier soon afterwards. Refusing the post of ambassador in London by the sultan Abdülhamid II, he resigned from public service and returned only after two decades, in 1908, as a member of the Senate of the Ottoman Parliament.

He was one of the founding members of the Freedom and Accord Party in 1911, favoring liberalism and more regional autonomy within the Empire, in opposition to the Committee of Union and Progress. He served as its first president from 24 November 1911 to June 1912.[2]

It was suggested that Damat Ferit Pasha be sent to the London conference to end the First Balkan War, but Grand Vizier Kamil Pasha opposed, saying "this man is crazy."[3]

On 11 June 1919, he officially confessed to massacres against Armenians and was a key figure and initiator of the Istanbul trials held directly after World War I to condemn to death the chief perpetrators of the genocide,[4][5][6] who were notably CUP members and long-time rivals of his own Freedom and Accord Party.

Grand Vezierates

His first office as grand vizier coincided with the Occupation of Smyrna by the Greek army and the ensuing tumultuous period. He assumed as the successor of Ahmet Tevfik Pasha on the 4 March 1919 and on the 9 March initiated a campaign of arrests of former ministers like Halil Menteşe, Ali Fethi Okyar and Ali Münif Yeğenağa amongst others.[7] Ferid Pasha was an ardent anglophile, who hoped to receive less harsh peace terms by presenting the Ottoman Empire as a more cooperative partner in the Eastern Mediterranean than Greece. He was known to say "After God, me and the Sultan relay on England". He was dismissed on 30 September 1919, but after two short-lived governments under Ali Rıza Pasha and Hulusi Salih Pasha, the Sultan Mehmet VI had to call him back to form a new government on 5 April 1920. He remained as Grand Vizier until 17 October 1920, forming two different cabinets in between.

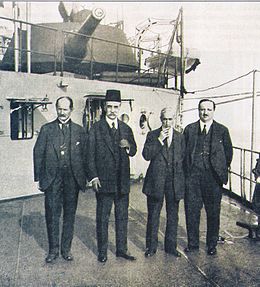

His second office coincided with the closure of the Ottoman Parliament under pressure from the British and French forces of occupation. Along with four other notables, he agreed to sign the Treaty of Sèvres, comprising disastrous conditions for Turkey, which caused an uproar of reaction towards him. A plan to assassinate him in early June 1920 failed when the lead conspirator Dramalı Rıza turned in his accomplices to the police, and Rıza was executed.[8]

Ferid Pasha was not one of the signatories of the Treaty itself,[9] but together with the three signatories he would be nevertheless stripped of his citizenship by the Grand National Assembly during the week of the treaty's signature and would head the list of 150 persona non grata of Turkey after the Turkish War of Independence. Ferid Pasha retorted by becoming increasingly hostile to the new nationalist movement led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha, which was centered in Ankara; Damat Ferid Pasha began to increasingly collaborate with the Allied occupation forces.

Even after his dismissal, and the formation of a new Ottoman Government under Ahmet Tevfik Pasha, he remained widely disliked (especially in Anatolia) and with the Turkish victory in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), he fled to Europe. He died in Nice, France, on 6 October 1923, the same day that Turkish troops recovered Constantinople, and was buried in the city of Sidon, Lebanon.

Impressions

According to Tevfik Pasha, "he [Ferid] surpassed even the Franks [westerners] in alafrangalık" (alafrangalıkta Frenkleri bile geçmiş idi).[10]

According to an article published in the Tevhid-i Efkâr newspaper at the time of his death:

"When [Ferid] he returned from London, he became a foreigner [alafranga] and eventually an enemy of Islam. The male and female servants in his house were all Greeks. In his words, speeches, and writings, he always talked of Greek and Latin proverbs, superstitions, and mythology. (...) In short, he became completely Westernized, but he was a man with a cosmopolitan spirit, completely devoid of national feelings."[11]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, Türkiye Yayınevi, İstanbul, 1971 (Turkish)

- ^ Ali Birinci, Hürriyet ve İtilâf Fırkası, Dergâh Yay. 1990, sf. 48-49 ve 55-64.)

- ^ Murat Bardakçı, Şahbaba, Pan Yay. 1998, sf. 110. Ancak başka kaynaklarda aynı anekdot 1918 Mondros Mütarekesi bağlamında ve sadrazam Ahmet İzzet Paşa'ya atfen anlatılır.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Lexikon der Völkermorde. Reinbek 1998. Rowohlt Verlag. p. 80 (German)

- ^ RECOGNIZING THE 81ST ANNIVERSARY OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE. United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 21 January 2013

- ^ Armenian Genocide Survivors Remember Archived 26 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Queens Gazette. Retrieved 21 January 2013

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N.; Akçam, Taner (2011). Judgment at Istanbul: The Armenian Genocide Trials. Berghahn Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-85745-251-1.

- ^ Gingeras 2022, p. 211.

- ^ See the signatories in the official text of the Treaty of Sèvres.

- ^ İbnülemin Mahmut Kemal İnal, Son Sadrazamlar, IV.2081.

- ^ Son Sadrazamlar, a.g.y.

Bibliography

Gingeras, Ryan (2022). The Last Days of the Ottoman Empire. Great Britain: Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-241-44432-0.