Cypriot wine

The Cypriot wine industry ranks 50th in the world in terms of total production quantity (10,302 tonnes),[1] and much higher on a per-capita basis. The wine industry is a significant contributor to the Cypriot economy through cultivation, production, employment, export and tourism.

Overview

Cyprus has been a vine-growing and wine-producing country for millennia and wine used to be a major factor of the Cypriot diet. There is archeological evidence that winemaking on the Mediterranean island may have existed as many as 6000 years ago.[2] Most wine production remains based on a few varieties of local grapes such as Mavro and Xynisteri (see table below) [3][4][5]

The most planted grape type is Mavro, it has dark color and literally translates as ‘black’ from Greek. Mavro is mainly used for producing the region's renowned wine Commandaria. The wine combines natural sweetness with high alcohol level and has similarities with a Passito or fortified wine. Commandaria can also be produced with the white grape variety Xynisteri.[6]

History

The history of wine in Cyprus can be broken down into four distinct periods.

Ancient

Exactly how far back wine production in Cyprus goes is unknown. Wine was being traded at least as early as 2300 BC, the date of a shipwreck (similar to the Kyrenia ship) carrying over 2,500 amphorae, discovered in 1999. Its origin and destination are unknown, but must have been along the trade route between Greece and Egypt.[7]

More recently, two discoveries have put that date back by a few more years. The first was the discovery of a Bronze Age (2500–2000 BC) perfumery near the village of Pyrgos.[8][9] Near this perfumery, an olive press, a winery, and copper smelting works were also discovered. Wine containers and even the seeds of grapes were unearthed.[10]

The second discovery involved an intriguing sequence of events. Dr. Porphyrios Dikaios, a major figure in Cypriot archaeology and once curator of the Cyprus Museum, had carried out excavations on the outskirts of Erimi village between 1932 and 1935. During these excavations, several fragments of round flasks were unearthed (amongst other artefacts). These pottery fragments ended up in the stores of the Cyprus Museum still unwashed in wooden boxes. They were dated to the chalcolithic period (between 3500BC-3000BC). In 2005, well after Dr Dikaios' death, the chemical signatures of 18 of these were examined by a team of Italian archaeologists led by Maria-Rosaria Belgiorno. Twelve of these showed traces of tartaric acid (a component of wine) proving that the 5,500-year-old vases were used for wine.[11]

Medieval to 1878

The history of wine on the island closely relates to its political and administrative history. During Lusignan rule, the island had close ties with the Crusader nations and especially the nobility of France. During this period, Commandaria wine won the Battle of the Wines, the first recorded wine tasting competition, which was staged by the French king Philip Augustus in the 13th century.[12] The event was recorded in a poem by Henry d'Andeli in 1224.[13]

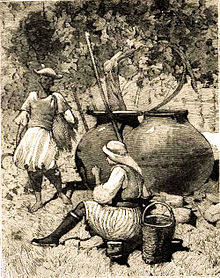

During the Ottoman occupation of the island, wine production went into decline. This was attributed to two factors: Islamic tradition and heavy taxation. Indicative are reports written mainly by French[14] and British travelers of the time; Cyrus Redding writes in 1851:

the vine grower of Cyprus hides from his neighbour the amount of his vintage, and always buries part of his produce for concealment; the exactions of the government are so great, that his profit upon what he allows to be seen is too little to remunerate him for his loss in time and labour.[15]

The quality of the wine produced also lagged behind times with Samuel Baker writing in 1879 "It should be understood that no quality of Cyprus wines is suitable to the English palate".[16]

1878–1980

1878 marked the handover of the island from Ottoman rule to the British Empire. British occupation brought a revival in the winemaking industry. Taxation rules changed and the local cottage industry began to expand. 1844 saw the foundation of one of the largest wineries surviving to date, that of ETKO by the Hadjipavlou family.[17] The Chaplin family (at Per Pedhi) was Hadjipavlou's main competitor until the arrival of KEO a company formed by a group of prominent local businessmen. KEO bought the Chaplin winery in 1928. In 1943, following a strike, a breakaway of trade union members from ETKO created a cooperative, LOEL.[18] In 1947 the vine-growers themselves created SODAP, a co-operative to "protect the rights of the growers".[19] These "big four" wine producers (a term widely used to refer to KEO, ETKO, SODAP and LOEL[20]) dominated the industry scene and survive to date.

The first wave of expansion for Cypriot wines came with the misfortunes of the European viticulture sector. The phylloxera epidemic that affected mainland Europe in the late 19th century had destroyed the majority of wine-producing vines. Cyprus, an island with strict quarantine controls, managed to remain unaffected.[21] As a consequence, demand for Cyprus grapes and wines coupled to the relatively high prices offered resulted in a mini boom for the industry. Further demand early in the early 20th century came from local consumption and from the regional forces of Britain and France in the Middle East. Cyprus produced quality cheap wine and spirits (mainly in the form of Cyprus brandy) and the big four companies prospered as a result.

The next big export product came in the form of Cyprus sherry. It was first marketed by that name in 1937 and was exported mainly to northern Europe. By the 1960s, Britain was consuming 13.6 million litres of Cyprus wines, half the island's production, mostly as sweet sherry. A British market research study of fortified wines in 1978 showed Emva Cream was the leading Cyprus sherry in terms of brand recognition, and second in that market only to Harveys' Bristol Cream.[22]

The island became the UK's third leading wine supplier behind France and Spain.[23] A major factor was that Cyprus sherry was more affordable than Spanish Sherry as British taxation favoured alcoholic beverages with an alcoholic content below the 15.5–18 percent bracket.[22] This competitive advantage was lost a few years later with the re-banding of the alcohol content taxation. The fortified wine market also began to shrink as a whole due to a change in consumer taste and as a result Cyprus sherry sales in the UK fell from their peak in the early 1970s by some 65 percent by the mid-1980s.[22] The final blow came when the EC ruled that as of January 1996 only fortified wine from Jerez could assume the title of sherry.[24]

The other big market for Cyprus wine during the same period was the Soviet bloc.[25] Large volumes of low-quality, mass-produced, blended wines were sold to the eastern bloc with the cooperative wine producers (LOEL and SODAP) taking the lion's share. This market began to dry up in the 1980s and vanished altogether with the fall of communism.[26] Indicative of the industry's mass production tactics comes in a report by The Times in 1968 commenting on "the end of an underwater pipeline off the coast of Limassol linking to tankers taking on not gas or oil but wine – 100 tons an hour of it – destined for about 40 countries throughout the world."[27]

1980 onwards

In response to the challenges faced by the industry the Cyprus vine-products commission began efforts to overhaul the sector in order to help it survive under the new circumstances. Reforms were intended to improve the quality rather than quantity of wine. Three initiatives were launched:

- Firstly, new varieties of grapes were introduced and (financial) incentives given for their cultivation. The varieties introduced were considered more suitable for quality wine production intended for wines more palatable to overseas markets (than local grapes). Examples include grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Carignan noir and Palomino (see complete table below).

- Secondly, incentives were given to create small regional wineries with a production capacity of 50,000 to 300,000 bottles per year.[28] This intended to promote better quality wines by reducing the distance grapes travelled from vineyard to winery.[29] The big four wineries were located in the large port cities of Limassol and Paphos so vine growers were forced to transport their harvest for miles in the summer heat. This had an effect on the quality of wine as the fermentation process had already begun during transport.[30] The knock on effect of this incentive also helped maintain the village population in the vine cultivating regions.

- Thirdly a new Appellation of Origin was launched in 2007.[31]

Quality levels & appellation system

The Cyprus vine products council has based wine denominations on European Union wine regulations[32] and is responsible for enforcing the regulations. Currently there are three accepted categories:

- Table wine. This is similar to the Vin de Table in France or Vino di Tavola in Italy.

- Local wine (Επιτραπέζιος Οίνος με Γεωγραφική Ένδειξη) which follows in similar fashion to the French Vin de pays and the Italian Indicazione Geografica Tipica. Regulations state that 85% of the grapes used in the production of such wine originates from the specific geographical regions and from the registered vineyards. Vines must be more than 4 years old with a controlled annual yield per cultivated hectare (55 hl/hectare or 70 hl/hectare depending on grape variety). Red wine must have a minimum of 11% alcohol content whilst rose and white wine a minimum of 10%.[33] There are four such designated areas: Lefkosia, Lemesos, Larnaca and Paphos.

- Protected designation of origin (or O.E.O.Π. standing for Οίνοι Ελεγχόμενης Ονομασίας Προέλευσης) is the most prestigious designation and in theory indicates a higher quality product. It is modelled on the French Appellation d'origine contrôlée, whereas the Italian equivalent is the Denominazione di origine controllata. Wines with this designation must originate from registered vineyards of an altitude above 600 or 750 meters depending on location. Vines should be more than 5 years old and yield is restricted to 36 or 45 hl per hectare depending on grape variety. There are further regulations dictating the grape composition and ageing process.[34]

In Cyprus, the national wine association that oversees the appellation system is the Cyprus Wine Products Council. This council governs the regulations for the country’s wine denominations, including seven Protected Designations of Origin (PDOs) and four Protected Geographical Indications (PGIs).[35]

Grape varieties

The climate allows for cultivation of most grape varieties. However local varietals (Mavro and Xynisteri) constitute the majority of current plantations. Maratheftiko today forms part of ancient red grape varietals vinified by most wineries wanting to exhibit the singularity of quality wine in Cyprus.

Table showing areas and quantities cultivated by Vines for Wines by variety:[36]

| Variety | 2016 Qty (kg) | % of total | 2012 Qty (kg)[37] | % of total | 2004 Qty (kg) | % of total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xynisteri | 4,324,005 | 33.3 | 4,067,716 | 15.4 | 11,102,700 | 15.4 |

| 2 | Mavro | 1,771,804 | 13.6 | 4,190,235 | 24,6 | 35,690,050 | 49.6 |

| 3 | Carignan noir | 1,007,063 | 7.5 | 1,605,161 | 9,7 | 8,894,350 | 12,4 |

| 4 | Shiraz | 859,724 | 6.6 | 560,352 | 3.4 | 149,750 | 0.2 |

| 5 | Maratheftiko | 443,131 | 3.4 | 430,083 | 2,6 | 204,660 | 0.3 |

| 6 | Cabernet[38] | 659,870 | 5.1 | 1,167,177 | 7.1 | 2,446,508 | 3.4 |

| 7 | Mataro | 425,045 | 3.3 | 515,035 | 3.1 | 1,196,940 | 1.7 |

| 8 | Lefkada (grape) | 303,337 | 2.3 | 372,288 | 2.3 | 149,750 | 0.2 |

| 9 | Chardonnay | 223,139 | 1.7 | 216,878 | 1.3 | n.a | n.a |

| 10 | Ofthalmo | 172,406 | 1.3 | 367,951 | 2.2 | 1,119,800 | 1.6 |

| 11 | Málaga | 153,668 | 1.2 | 128,034 | 0.8 | 1,501,930 | 2.1 |

| 12 | Merlot Noir | 151,999 | 1.2 | 166,563 | 1.0 | n.a | n.a |

| 13 | Grenache noir | 151,658 | 1.2 | 201,804 | 1.2 | 960,611 | 1.3 |

| 14 | Semillion | 147,726 | 1.1 | 162,446 | 1.0 | n.a | n.a |

| 15 | Alicante Bouschet | 140,280 | 1.1 | 219,014 | 1.3 | 589,105 | 0.8 |

| 16 | Sauvignon Blanc | 125,965 | 1.0 | 73,654 | 0.4 | n.a | n.a |

| 17 | Palomino | 84,247 | 0.7 | 300,840 | 1.8 | 2,509,350 | 3.5 |

| 18 | Spourtiko | 50,472 | 0.4 | 31,016 | 0.2 | n.a | n.a |

| 19 | Promara | 12,148 | 0.1 | 4,180 | 0.03 | n.a | n.a |

| 20 | Morokanella | 8,876 | 0.1 | 3,540 | 0.02 | n.a | n.a |

| 21 | Yiannoudi | 8,758 | 0.1 | 3,135 | 0.02 | n.a | n.a |

| Total[39] | 12,992,975 | 16,566,786 | 71,996,587 |

Wine Museum

The Cyprus Wine Museum is located in the heart of the wine-producing area in Erimi village. The Museum is housed in the site where archaeologists have discovered wine dating back to 3.500 BC. The area has a 5500-year history of wine making and is located at the crossroads of the Cyprus wine routes, in close proximity to the prehistoric settlement of Sotira, where the oldest remains of grape seeds have been found and near to Kolossi Castle, a medieval Commanderie of The Knights Hospitaller that give the name to the Commandaria Wine first produced by them. Photographic material and audiovisual presentations, as well as ancient jars, crocks, medieval pots, old documents and instruments can be found relating to the history of wine in Cyprus.[citation needed]

Wine routes

- Koumandaria

- Laona – Akamas

- Vouni Panagias – Ambelitis

- Krasochoria Lemesou

- Pitsilia

- Nicosia – Larnaka

- Diarizos Valley

Turkish Cypriot Wine

For Turkish Cypriots, the first commercial wine projects began with research in the 1990s,[40] with Chateau St Hilarion as a notable winery based in the Village of Gećitköy to the west of Lapithos. It was established in 2000, and with the aid of international wine consultant, Keith Grainger, the first commercial vintage was produced in 2004.[41] Today, there are two ranges of wines produced by the winery: Chateau St Hilarion, the domaine wine produced from grapes grown in the vineyards at Gećitköy and Morphou, and the Levant, which is produced from grapes purchased from local farmers. Chateau St Hilarion is currently researching the viability of using and introducing various new grape varieties to the island.[41]

ETEL Winery in Ilgaz village was established in 2016.

See also

References

- ^ "Wine production by country". Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Κρασί κυπριακό : Μια παράδοση 5500 χρόνων". foodmuseum.cs.ucy.ac.cy (in Greek). Cyprus Food Virtual Museum. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Wine Searcher: Cyprus Wine

- ^ "Wine Mag: Wines of Cyprus - Nectar of the Gods". Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Independent: Wines in Cyprus: A taste of things to come

- ^ "Cyprian wine regions - Wine tasting & tours | Winetourism.com". www.winetourism.com. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Phaneuf, Brett; Thomas Dettweiler; Thomas Bethge (March–April 2001). "Special Report: Deepest Wreck". Archaeology. Vol. 54, no. 2. Archaeological Institute of America. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ Morgan, Tabitha (19 March 2005). "Bronze Age perfume 'discovered'". BBC. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ Theodoulou, Michael (25 February 2005). "Archaeological dig sniffs out world's oldest perfumery". The Scotsman. UK. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ Molyva, Demetra (14 May 2005). "Most ancient wine in the Mediterranean is Cypriot". Cyprus Weekly. Stampa. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ "Cyprus 'first to make wine'". Decanter. 16 May 2005. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ O'Donnell, Ben (31 May 2011). "The First Wine Competition?". Wine Spectator. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ d'Andeli, Henri. "La bataille des vins" (in French). Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Sigisbert, Charles (1801). Voyage en Grèce et en Turquie, fait par ordre de Louis XVI (pp106) (in French). Chez F. Buisson. Retrieved 10 May 2007 – via GoogleBooks (fulltext).

- ^ Redding, Cyrus (1851). "A History and Description of Modern Wine (see p.36)". GoogleBooks (fulltext). H. G. Bohn. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ Samuel W. Baker (1879). Cyprus, as I Saw it in 1879. Project Gutenberg (Etext edition, 2003). p. 271.

- ^ Kassianos, George (28 September 2003). "New blood and a renewed vision". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ "LOEL Ltd – Company profile on home website". Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "SODAP Ltd – Company profile on home website". Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "Join the revolution". Lincolnshire Echo. 11 August 2006.

- ^ "Cyprus wine comes of age". Caterer and Hotelkeeper (Archive). CatererSearch. 13 January 1994. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ a b c Fernandez-Garcia, Eva (ed.). "Marketing Strategies in Sherry Wine Industry during the Twentieth Century" (PDF). Retrieved 10 October 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Knipe, Michael (1 October 2002). "Lionheart's liquid legacy". The Times. p. 35.

- ^ Rose, Anthony (13 January 1996). "Sherry gets real". The Independent: 42. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ Skinner, Patrick. "Cyprus Wines- 1,000 Years of History". Cyprus Wine Product Council.

- ^ Leonidou, Leo. "Quality not quantity". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 2 November 2006.

- ^ Reed, Arthur (19 June 1968). "Pipeline Wine". The Times Digital Archive. No. 57281. pp. V, col A. Archived from the original on 6 September 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ^ "Wines & Spirits – Regional Wineries". Cyprus High Commission Trade Centre. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Gilby, Caroline (11 August 2006). "A new era for Cyprus". Harpers. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ^ "Cyprus and Her Wines". Wine&Dine. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ^ "Appelation of Origin – Οίνοι Ελεγχόμενης Ονομασίας Προέλευσης (Ο.Ε.Ο.Π.)" (PDF) (in Greek). Vine Products Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ^ "Register of designations of origin and geographical indications protected in the EU in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013" (Database). E-Bacchus. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Τοπικοί Οίνοι (Local wine)" (PDF) (in Greek). Vine Products Council of Cyprus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Οίνοι Ελεγχόμενης Ονομασίας Προέλευσης (Ο.Ε.Ο.Π.) (PDF) (in Greek). Vine Products Council of Cyprus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ "Discover the wines regions, subregions and grape varietals and wines of Cyprus". www.vinerra.com. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "Evoinos. Monitoring of Vine & Wine production in Cyprus in consultation of Viticultural section of the Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment". Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ Figures reflect quantities in kilograms delivered to local wineries (does not include grapes used for other purposes e.g. sultana production, grape juice production etc.)

- ^ Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc combined

- ^ Includes several other less common varieties not listed in table

- ^ Marion Stuart. "Real Ale Reality". KKT North Cyprus News (13). Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ a b Mustafa and Sengul Seyfi. "North Cyprus Wines About Us". Retrieved 31 October 2018.

External links

- Wine Cyprus Blog

- Cyprus Wine Products Council – in Greek/English

- Cyprus Wine Competition Results

- The Cyprus wine story – Information material from the Cyprus Tourism board.

- Cyprus Wine tour: tour dei vini a Cipro - in Italian Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The Cyprus Wine Museum