Copper(II) acetate

Small crystals of copper(II) acetate | |

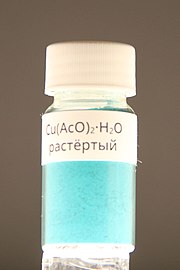

Copper(II) acetate monohydrate | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name Tetra-μ2-acetatodiaquadicopper(II) | |

| Other names Copper(II) ethanoate Cupric acetate Copper acetate Verdigris | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.049 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 3077 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Cu(CH3COO)2 | |

| Molar mass | 181.63 g/mol (anhydrous) 199.65 g/mol (hydrate) |

| Appearance | Dark green crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless (hydrate) |

| Density | 1.882 g/cm3 (hydrate) |

| Melting point | 115 °C (anhydrous) [1]

Undetermined (hydrate)[2] |

| Boiling point | 240 °C (464 °F; 513 K) |

| Hydrate: 7.2 g/100 mL (cold water) 20 g/100 mL (hot water) | |

| Solubility | Soluble in alcohol Slightly soluble in ether and glycerol |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.545 (hydrate) |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301, H302, H311, H314, H410, H411, H412 | |

| P260, P264, P270, P273, P280, P301+P310, P301+P312, P301+P330+P331, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P312, P321, P322, P330, P361, P363, P391, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

710 mg/kg oral rat[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1 mg/m3 (as Cu)[3] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1 mg/m3 (as Cu)[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

TWA 100 mg/m3 (as Cu)[3] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Baker MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Copper(II) acetate, also referred to as cupric acetate, is the chemical compound with the formula Cu(OAc)2 where AcO− is acetate (CH

3CO−

2). The hydrated derivative, Cu2(OAc)4(H2O)2, which contains one molecule of water for each copper atom, is available commercially. Anhydrous copper(II) acetate is a dark green crystalline solid, whereas Cu2(OAc)4(H2O)2 is more bluish-green. Since ancient times, copper acetates of some form have been used as fungicides and green pigments. Today, copper acetates are used as reagents for the synthesis of various inorganic and organic compounds.[5] Copper acetate, like all copper compounds, emits a blue-green glow in a flame.

Structure

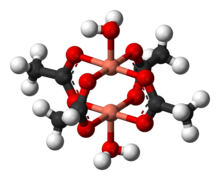

Copper acetate hydrate adopts the paddle wheel structure seen also for related Rh(II) and Cr(II) tetraacetates.[6][7] One oxygen atom on each acetate is bound to one copper atom at 1.97 Å (197 pm). Completing the coordination sphere are two water ligands, with Cu–O distances of 2.20 Å (220 pm). The two copper atoms are separated by only 2.62 Å (262 pm), which is close to the Cu–Cu separation in metallic copper.[8][9][10][11] The two copper centers interact resulting in a diminishing of the magnetic moment such that at temperatures below 90 K, Cu2(OAc)4(H2O)2 is essentially diamagnetic. Cu2(OAc)4(H2O)2 was a critical step in the development of modern theories for antiferromagnetic exchange coupling, which ascribe its low-temperature diamagnetic behavior to cancellation of the two opposing spins on the adjacent copper atoms.[12]

Synthesis

Copper(II) acetate is prepared industrially by heating copper(II) hydroxide or basic copper(II) carbonate with acetic acid.[5]

Uses in chemical synthesis

Copper(II) acetate has found some use as an oxidizing agent in organic syntheses. In the Eglinton reaction Cu2(OAc)4 is used to couple terminal alkynes to give a 1,3-diyne:[13][14]

- Cu2(OAc)4 + 2 RC≡CH → 2 CuOAc + RC≡C−C≡CR + 2 HOAc

The reaction proceeds via the intermediacy of copper(I) acetylides, which are then oxidized by the copper(II) acetate, releasing the acetylide radical. A related reaction involving copper acetylides is the synthesis of ynamines, terminal alkynes with amine groups using Cu2(OAc)4.[15] It has been used for hydroamination of acrylonitrile.[16]

It is also an oxidising agent in Barfoed's test.

It reacts with arsenic trioxide to form copper acetoarsenite, a powerful insecticide and fungicide called Paris green.

Related compounds

Heating a mixture of anhydrous copper(II) acetate and copper metal affords copper(I) acetate:[17][18]

- Cu + Cu(OAc)2 → 2 CuOAc

Unlike the copper(II) derivative, copper(I) acetate is colourless and diamagnetic.

"Basic copper acetate" is prepared by neutralizing an aqueous solution of copper(II) acetate. The basic acetate is poorly soluble. This material is a component of verdigris, the blue-green substance that forms on copper during long exposures to atmosphere.

Other uses

A mixture of copper acetate and ammonium chloride is used to chemically color copper with a bronze patina.[19]

Mineralogy

The mineral hoganite is a naturally occurring form of copper(II) acetate.[20][21] A related mineral, also containing calcium, is paceite.[21] Both are very rare.[22][23]

References

- ^ "Copper(II) acetate | C4H6CuO4 | ChemSpider".

- ^ Trimble, R. F. (1976). "Copper(II) acetate monohydrate - An erroneous melting point". Journal of Chemical Education. 53 (6): 397. Bibcode:1976JChEd..53..397T. doi:10.1021/ed053p397.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0150". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Mineral Safety Data Sheet: Copper (II) Acetate, Monohydrate" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ a b Richardson, H. Wayne. "Copper Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_567. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Van Niekerk, J. N.; Schoening, F. R. L. (1953). "X-Ray Evidence for Metal-to-Metal Bonds in Cupric and Chromous Acetate". Nature. 171 (4340): 36–37. Bibcode:1953Natur.171...36V. doi:10.1038/171036a0. S2CID 4292992.

- ^ Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Clarendon Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Catterick, J.; Thornton, P. (1977). "Structures and physical properties of polynuclear carboxylates". Adv. Inorg. Chem. Radiochem. Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry. 20: 291–362. doi:10.1016/s0065-2792(08)60041-2. ISBN 9780120236206.

- ^ van Niekerk, J. N.; Schoening, F. R. L. (1953-03-10). "A new type of copper complex as found in the crystal structure of cupric acetate, Cu2(CH3COO)4.2H2O". Acta Crystallographica. 6 (3): 227–232. Bibcode:1953AcCry...6..227V. doi:10.1107/S0365110X53000715. ISSN 0365-110X.

- ^ Meester, Patrice de; Fletcher, Steven R.; Skapski, Andrzej C. (1973-01-01). "Refined crystal structure of tetra-µ-acetato-bisaquodicopper(II)". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (23): 2575–2578. doi:10.1039/DT9730002575. ISSN 1364-5447.

- ^ Brown, G. M.; Chidambaram, R. (1973-11-15). "Dinuclear copper(II) acetate monohydrate: a redetermination of the structure by neutron-diffraction analysis". Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry. 29 (11): 2393–2403. Bibcode:1973AcCrB..29.2393B. doi:10.1107/S0567740873006758. ISSN 0567-7408.

- ^ Carlin, R. L. (1986). Magnetochemistry. Berlin: Springer. pp. 77–82. ISBN 978-3642707353.

- ^ Stöckel, K.; Sondheimer, F. "[18]Annulene". Organic Syntheses. 54: 1. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.054.0001; Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 68.

- ^ Campbell, I. D.; Eglinton, G. "Diphenyldiacetylene". Organic Syntheses. 45: 39. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.045.0039; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 517.

- ^ Vogel, P.; Srogl, J. (2005). "Copper(II) Acetate". EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc194.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-84289-8..

- ^ Heininger, S. A. "3-(o-Chloroanilino)propionitrile". Organic Syntheses. 38: 14. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.038.0014; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 146.

- ^ Kirchner, S. J.; Fernando, Q. (2007). "Copper(I) Acetate". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 20. pp. 53–55. doi:10.1002/9780470132517.ch16. ISBN 9780470132517.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Parish, E. J.; Kizito, S. A. (2001). "Copper(I) Acetate". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc193. ISBN 0471936235.

- ^ Budija, Goran. "Collection of formulas for the chemical,electrochemical and heat colouring of metals,the cyanide free immersion plating and electroplating" (PDF). Finishing.com. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Musumeci, Anthony; Frost, Ray L. (2007-05-01). "A spectroscopic and thermoanalytical study of the mineral hoganite". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 67 (1): 48–57. Bibcode:2007AcSpA..67...48M. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2006.05.037. ISSN 1386-1425. PMID 17321784.

- ^ a b Hibbs, D. E.; Kolitsch, U.; Leverett, P.; Sharpe, J. L.; Williams, P. A. (June 2002). "Hoganite and paceite, two new acetate minerals from the Potosi mine, Broken Hill, Australia". Mineralogical Magazine. 66 (3): 459–464. Bibcode:2002MinM...66..459H. doi:10.1180/0026461026630042. ISSN 0026-461X. S2CID 97116531.

- ^ "Paceite".

- ^ "List of Minerals". 21 March 2011.

External links

- Copper.org – Other Copper Compounds Archived 2013-08-15 at the Wayback Machine 5 Feb. 2006

- Infoplease.com – Paris green 6 Feb. 2006

- Verdigris – History and Synthesis 6 Feb. 2006

- Australian - National Pollutant Inventory 8 Aug. 2016

- USA NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information 8 Aug. 2016