Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

| The Enigma cipher machine |

|---|

| Enigma machine |

| Breaking Enigma |

| Related |

Cryptanalysis of the Enigma ciphering system enabled the western Allies in World War II to read substantial amounts of Morse-coded radio communications of the Axis powers that had been enciphered using Enigma machines. This yielded military intelligence which, along with that from other decrypted Axis radio and teleprinter transmissions, was given the codename Ultra.

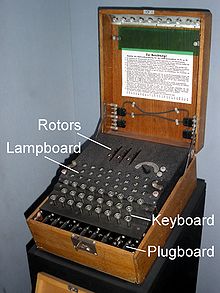

The Enigma machines were a family of portable cipher machines with rotor scramblers.[1] Good operating procedures, properly enforced, would have made the plugboard Enigma machine unbreakable to the Allies at that time.[2][3][4]

The German plugboard-equipped Enigma became the principal crypto-system of the German Reich and later of other Axis powers. In December 1932 it was broken by mathematician Marian Rejewski at the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau,[5] using mathematical permutation group theory combined with French-supplied intelligence material obtained from a German spy. By 1938 Rejewski had invented a device, the cryptologic bomb, and Henryk Zygalski had devised his sheets, to make the cipher-breaking more efficient. Five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, in late July 1939 at a conference just south of Warsaw, the Polish Cipher Bureau shared its Enigma-breaking techniques and technology with the French and British.

During the German invasion of Poland, core Polish Cipher Bureau personnel were evacuated via Romania to France, where they established the PC Bruno signals intelligence station with French facilities support. Successful cooperation among the Poles, French, and British continued until June 1940, when France surrendered to the Germans.

From this beginning, the British Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park built up an extensive cryptanalytic capability. Initially the decryption was mainly of Luftwaffe (German air force) and a few Heer (German army) messages, as the Kriegsmarine (German navy) employed much more secure procedures for using Enigma. Alan Turing, a Cambridge University mathematician and logician, provided much of the original thinking that led to upgrading of the Polish cryptologic bomb used in decrypting German Enigma ciphers. However, the Kriegsmarine introduced an Enigma version with a fourth rotor for its U-boats, resulting in a prolonged period when these messages could not be decrypted. With the capture of cipher keys and the use of much faster US Navy bombes, regular, rapid reading of U-boat messages resumed.

General principles

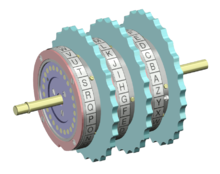

The Enigma machines produced a polyalphabetic substitution cipher. During World War I, inventors in several countries realised that a purely random key sequence, containing no repetitive pattern, would, in principle, make a polyalphabetic substitution cipher unbreakable.[6] This led to the development of rotor machines which alter each character in the plaintext to produce the ciphertext, by means of a scrambler comprising a set of rotors that alter the electrical path from character to character, between the input device and the output device. This constant altering of the electrical pathway produces a very long period before the pattern—the key sequence or substitution alphabet—repeats.

Decrypting enciphered messages involves three stages, defined somewhat differently in that era than in modern cryptography.[7] First, there is the identification of the system in use, in this case Enigma; second, breaking the system by establishing exactly how encryption takes place, and third, solving, which involves finding the way that the machine was set up for an individual message, i.e. the message key.[8] Today, it is often assumed that an attacker knows how the encipherment process works (see Kerckhoffs's principle) and breaking is often used for solving a key. Enigma machines, however, had so many potential internal wiring states that reconstructing the machine, independent of particular settings, was a very difficult task.

The Enigma machine

The Enigma rotor machine was potentially an excellent system. It generated a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, with a period before repetition of the substitution alphabet that was much longer than any message, or set of messages, sent with the same key.

A major weakness of the system, however, was that no letter could be enciphered to itself. This meant that some possible solutions could quickly be eliminated because of the same letter appearing in the same place in both the ciphertext and the putative piece of plaintext. Comparing the possible plaintext Keine besonderen Ereignisse (literally, "no special occurrences"—perhaps better translated as "nothing to report"; a phrase regularly used by one German outpost in North Africa), with a section of ciphertext, might produce the following:

| Ciphertext | O | H | J | Y | P | D | O | M | Q | N | J | C | O | S | G | A | W | H | L | E | I | H | Y | S | O | P | J | S | M | N | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position 1 | K | E | I | N | E | B | E | S | O | N | D | E | R | E | N | E | R | E | I | G | N | I | S | S | E | ||||||

| Position 2 | K | E | I | N | E | B | E | S | O | N | D | E | R | E | N | E | R | E | I | G | N | I | S | S | E | ||||||

| Position 3 | K | E | I | N | E | B | E | S | O | N | D | E | R | E | N | E | R | E | I | G | N | I | S | S | E | ||||||

| Positions 1 and 3 for the possible plaintext are impossible because of matching letters.

The red cells represent these clashes. Position 2 is a possibility. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Structure

The mechanism of the Enigma consisted of a keyboard connected to a battery and a current entry plate or wheel (German: Eintrittswalze), at the right hand end of the scrambler (usually via a plugboard in the military versions).[9] This contained a set of 26 contacts that made electrical connection with the set of 26 spring-loaded pins on the right hand rotor. The internal wiring of the core of each rotor provided an electrical pathway from the pins on one side to different connection points on the other. The left hand side of each rotor made electrical connection with the rotor to its left. The leftmost rotor then made contact with the reflector (German: Umkehrwalze). The reflector provided a set of thirteen paired connections to return the current back through the scrambler rotors, and eventually to the lampboard where a lamp under a letter was illuminated.[10]

Whenever a key on the keyboard was pressed, the stepping motion was actuated, advancing the rightmost rotor one position. Because it moved with each key pressed it is sometimes called the fast rotor. When a notch on that rotor engaged with a pawl on the middle rotor, that too moved; and similarly with the leftmost ('slow') rotor.

There are a huge number of ways that the connections within each scrambler rotor—and between the entry plate and the keyboard or plugboard or lampboard—could be arranged. For the reflector plate there are fewer, but still a large number of options to its possible wirings.[11]

Each scrambler rotor could be set to any one of its 26 starting positions (any letter of the alphabet). For the Enigma machines with only three rotors, their sequence in the scrambler—which was known as the wheel order (WO) to Allied cryptanalysts—could be selected from the six that are possible.

| Left | Middle | Right |

|---|---|---|

| I | II | III |

| I | III | II |

| II | I | III |

| II | III | I |

| III | I | II |

| III | II | I |

Later Enigma models included an alphabet ring like a tyre around the core of each rotor. This could be set in any one of 26 positions in relation to the rotor's core. The ring contained one or more notches that engaged with a pawl that advanced the next rotor to the left.[12]

Later still, the three rotors for the scrambler were selected from a set of five or, in the case of the German Navy, eight rotors. The alphabet rings of rotors VI, VII, and VIII contained two notches which, despite shortening the period of the substitution alphabet, made decryption more difficult.

Most military Enigmas also featured a plugboard (German: Steckerbrett). This altered the electrical pathway between the keyboard and the entry wheel of the scrambler and, in the opposite direction, between the scrambler and the lampboard. It did this by exchanging letters reciprocally, so that if A was plugged to G then pressing key A would lead to current entering the scrambler at the G position, and if G was pressed the current would enter at A. The same connections applied for the current on the way out to the lamp panel.

To decipher German military Enigma messages, the following information would need to be known.

Logical structure of the machine (unchanging)

- The wiring between the keyboard (and lampboard) and the entry plate.

- The wiring of each rotor.

- The number and position(s) of turnover notches on the rings of the rotors.

- The wiring of the reflectors.

Internal settings (usually changed less frequently than external settings)

- The selection of rotors in use and their ordering on the spindle (Walzenlage or "wheel order").

- The positions of the alphabet ring in relation to the core of each rotor in use (Ringstellung or "ring settings").

External settings (usually changed more frequently than internal settings)

- The plugboard connections (Steckerverbindungen or "stecker values").

- The rotor positions at the start of enciphering the text of the message.

Discovering the logical structure of the machine may be called "breaking" it, a one-off process except when changes or additions were made to the machines. Finding the internal and external settings for one or more messages may be called "solving"[13] – although breaking is often used for this process as well.

Security properties

The various Enigma models provided different levels of security. The presence of a plugboard (Steckerbrett) substantially increased the security of the encipherment. Each pair of letters that were connected together by a plugboard lead were referred to as stecker partners, and the letters that remained unconnected were said to be self-steckered.[14] In general, the unsteckered Enigma was used for commercial and diplomatic traffic and could be broken relatively easily using hand methods, while attacking versions with a plugboard was much more difficult. The British read unsteckered Enigma messages sent during the Spanish Civil War,[15] and also some Italian naval traffic enciphered early in World War II.

The strength of the security of the ciphers that were produced by the Enigma machine was a product of the large numbers associated with the scrambling process.

- It produced a polyalphabetic substitution cipher with a period (16 900) that was many times the length of the longest message.

- The 3-rotor scrambler could be set in 26 × 26 × 26 = 17 576 ways, and the 4-rotor scrambler in 26 × 17 576 = 456 976 ways.

- With L leads on the plugboard, the number of ways that pairs of letters could be interchanged was

However, the way that Enigma was used by the Germans meant that, if the settings for one day (or whatever period was represented by each row of the setting sheet) were established, the rest of the messages for that network on that day could quickly be deciphered.[18]

The security of Enigma ciphers did have fundamental weaknesses that proved helpful to cryptanalysts.

- A letter could never be encrypted to itself, a consequence of the reflector.[19] This property was of great help in using cribs—short sections of plaintext thought to be somewhere in the ciphertext—and could be used to eliminate a crib in a particular position. For a possible location, if any letter in the crib matched a letter in the ciphertext at the same position, the location could be ruled out.[20] It was this feature that the British mathematician and logician Alan Turing exploited in designing the British bombe.

- The plugboard connections were reciprocal, so that if A was plugged to N, then N likewise became A. It was this property that led mathematician Gordon Welchman at Bletchley Park to propose that a diagonal board be introduced into the bombe, substantially reducing the number of incorrect rotor settings that the bombes found.[21]

- The notches in the alphabet rings of rotors I to V were in different positions, which helped cryptanalysts to work out the wheel order by observing when the middle rotor was turned over by the right-hand rotor.[22]

- There were weaknesses, in both policies and practice, in the way some Enigma versions were used.[clarification needed]

- Critical material was disclosed without notice.[clarification needed]

Key setting

Enigma featured the major operational convenience of being symmetrical (or self-inverse). This meant that decipherment worked in the same way as encipherment, so that when the ciphertext was typed in, the sequence of lamps that lit yielded the plaintext.

Identical setting of the machines at the transmitting and receiving ends was achieved by key setting procedures. These varied from time to time and across different networks. They consisted of setting sheets in a codebook.[23][24] which were distributed to all users of a network, and were changed regularly. The message key was transmitted in an indicator[25] as part of the message preamble. The word key was also used at Bletchley Park to describe the network that used the same Enigma setting sheets. Initially these were recorded using coloured pencils and were given the names red, light blue etc., and later the names of birds such as kestrel.[26] During World War II the settings for most networks lasted for 24 hours, although towards the end of the war, some were changed more frequently.[27] The sheets had columns specifying, for each day of the month, the rotors to be used and their positions, the ring positions and the plugboard connections. For security, the dates were in reverse chronological order down the page, so that each row could be cut off and destroyed when it was finished with.[28]

| Datum [Date] |

Walzenlage [Rotors] |

Ringstellung [Ring settings] |

Steckerverbindungen [Plugboard settings] |

Grundstellung [Initial rotor settings] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | I II III |

W N M | HK CN IO FY JM LW | RAO |

| 30 | III I II |

C K U | CK IZ QT NP JY GW | VQN |

| 29 | II III I |

B H N | FR LY OX IT BM GJ | XIO |

Up until 15 September 1938,[30] the transmitting operator indicated to the receiving operator(s) how to set their rotors, by choosing a three letter message key (the key specific to that message) and enciphering it twice using the specified initial ring positions (the Grundstellung). The resultant 6-letter indicator, was then transmitted before the enciphered text of the message.[31] Suppose that the specified Grundstellung was RAO, and the chosen 3-letter message key was IHL, the operator would set the rotors to RAO and encipher IHL twice. The resultant ciphertext, DQYQQT, would be transmitted, at which point the rotors would be changed to the message key (IHL) and then the message itself enciphered. The receiving operator would use the specified Grundstellung RAO to decipher the first six letters, yielding IHLIHL. The receiving operator, seeing the repeated message key would know that there had been no corruption and use IHL to decipher the message.

The weakness in this indicator procedure came from two factors. First, use of a global Grundstellung —this was changed in September 1938 so that the operator selected his initial position to encrypt the message key, and sent the initial position in clear followed by the enciphered message key. The second problem was the repetition of message key within the indicator, which was a serious security flaw.[32] The message setting was encoded twice, resulting in a relation between first and fourth, second and fifth, and third and sixth character. This security problem enabled the Polish Cipher Bureau to break into the pre-war Enigma system as early as 1932. On 1 May 1940 the Germans changed the procedures to encipher the message key only once.

British efforts

In 1927, the UK openly purchased a commercial Enigma. Its operation was analysed and reported. Although a leading British cryptographer, Dilly Knox (a veteran of World War I and the cryptanalytical activities of the Royal Navy's Room 40), worked on decipherment he had only the messages he generated himself to practice with. After Germany supplied modified commercial machines to the Nationalist side in the Spanish Civil War, and with the Italian Navy (who were also aiding the Nationalists) using a version of the commercial Enigma that did not have a plugboard, Britain could intercept the radio broadcast messages. In April 1937[33] Knox made his first decryption of an Enigma encryption using a technique that he called buttoning up to discover the rotor wirings[34] and another that he called rodding to solve messages.[35] This relied heavily on cribs and on a crossword-solver's expertise in Italian, as it yielded a limited number of spaced-out letters at a time.

Britain had no ability to read the messages broadcast by Germany, which used the military Enigma machine.[36]

Polish breakthroughs

In the 1920s the German military began using a 3-rotor Enigma, whose security was increased in 1930 by the addition of a plugboard.[37] The Polish Cipher Bureau sought to break it because of the threat that Poland faced from Germany, but the early attempts did not succeed. Mathematicians having earlier rendered great services in breaking Russian ciphers and codes, in early 1929 the Polish Cipher Bureau invited mathematics students at Poznań University – who had a good knowledge of the German language due to the area having only after World War I been liberated from Germany – to take a course in cryptology.[38]

After the course, the Bureau recruited some students to work part-time at a Bureau branch set up in Poznań. On 1 September 1932, 27-year-old mathematician Marian Rejewski and two fellow Poznań University mathematics graduates, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Różycki, were hired by the Bureau in Warsaw.[39] Their first task was reconstructing a four-letter German naval code.[40]

Near the end of 1932 Rejewski was asked to work a couple of hours a day at breaking the Enigma cipher. His work on it may have begun in late October or early November 1932.[41]

Rejewski's characteristics method

Marian Rejewski quickly spotted the Germans' major procedural weaknesses of specifying a single indicator setting (Grundstellung) for all messages on a network for a day, and repeating the operator's chosen message key in the enciphered 6-letter indicator. Those procedural mistakes allowed Rejewski to decipher the message keys without knowing any of the machine's wirings. In the above example of DQYQQT being the enciphered indicator, it is known that the first letter D and the fourth letter Q represent the same letter, enciphered three positions apart in the scrambler sequence. Similarly with Q and Q in the second and fifth positions, and Y and T in the third and sixth. Rejewski exploited this fact by collecting a sufficient set of messages enciphered with the same indicator setting, and assembling three tables for the 1,4, the 2,5, and the 3,6 pairings. Each of these tables might look something like the following:

| First letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fourth letter | N | S | Y | Q | T | I | C | H | A | F | E | X | J | P | U | L | W | R | Z | K | G | O | V | M | D | B |

A path from one first letter to the corresponding fourth letter, then from that letter as the first letter to its corresponding fourth letter, and so on until the first letter recurs, traces out a cycle group.[42] The following table contains six cycle groups.

| Cycle group starting at A (9 links) | (A, N, P, L, X, M, J, F, I, A) |

|---|---|

| Cycle group starting at B (3 links) | (B, S, Z, B) |

| Cycle group starting at C (9 links) | (C, Y, D, Q, W, V, O, U, G, C) |

| Cycle group starting at E (3 links) | (E, T, K, E) |

| Cycle group starting at H (1 link) | (H, H) |

| Cycle group starting at R (1 link) | (R, R) |

Rejewski recognised that a cycle group must pair with another group of the same length. Even though Rejewski did not know the rotor wirings or the plugboard permutation, the German mistake allowed him to reduce the number of possible substitution ciphers to a small number. For the 1,4 pairing above, there are only 1×3×9=27 possibilities for the substitution ciphers at positions 1 and 4.

Rejewski also exploited cipher clerk laziness. Scores of messages would be enciphered by several cipher clerks, but some of those messages would have the same encrypted indicator. That meant that both clerks happened to choose the same three letter starting position. Such a collision should be rare with randomly selected starting positions, but lazy cipher clerks often chose starting positions such as "AAA", "BBB", or "CCC". Those security mistakes allowed Rejewski to solve each of the six permutations used to encipher the indicator.

That solution was an extraordinary feat. Rejewski did it without knowing the plugboard permutation or the rotor wirings. Even after solving for the six permutations, Rejewski did not know how the plugboard was set or the positions of the rotors. Knowing the six permutations also did not allow Rejewski to read any messages.

The spy and the rotor wiring

Before Rejewski started work on the Enigma, the French had a spy, Hans-Thilo Schmidt, who worked at Germany's Cipher Office in Berlin and had access to some Enigma documents. Even with the help of those documents, the French did not make progress on breaking the Enigma. The French decided to share the material with their British and Polish allies. In a December 1931 meeting, the French provided Gwido Langer, head of the Polish Cipher Bureau, with copies of some Enigma material. Langer asked the French for more material, and Gustave Bertrand of French Military Intelligence quickly obliged; Bertrand provided additional material in May and September 1932.[43] The documents included two German manuals and two pages of Enigma daily keys.[44][45]

In December 1932, the Bureau provided Rejewski with some German manuals and monthly keys. The material enabled Rejewski to achieve "one of the most important breakthroughs in cryptologic history"[46] by using the theory of permutations and groups to work out the Enigma scrambler wiring.[47][48]

Rejewski could look at a day's cipher traffic and solve for the permutations at the six sequential positions used to encipher the indicator. Since Rejewski had the cipher key for the day, he knew and could factor out the plugboard permutation. He assumed the keyboard permutation was the same as the commercial Enigma, so he factored that out. He knew the rotor order, the ring settings, and the starting position. He developed a set of equations that would allow him to solve for the rightmost rotor wiring assuming the two rotors to the left did not move.[49]

He attempted to solve the equations, but failed with inconsistent results. After some thought, he realised one of his assumptions must be wrong.

Rejewski found that the connections between the military Enigma's keyboard and the entry ring were not, as in the commercial Enigma, in the order of the keys on a German typewriter. He made an inspired correct guess that it was in alphabetical order.[50] Britain's Dilly Knox was astonished when he learned, in July 1939, that the arrangement was so simple.[51][52]

With the new assumption, Rejewski succeeded in solving the wiring of the rightmost rotor. The next month's cipher traffic used a different rotor in the rightmost position, so Rejewski used the same equations to solve for its wiring. With those rotors known, the remaining third rotor and the reflector wiring were determined. Without capturing a single rotor to reverse engineer, Rejewski had determined the logical structure of the machine.

The Polish Cipher Bureau then had some Enigma machine replicas made; the replicas were called "Enigma doubles".

The grill method

The Poles now had the machine's wiring secrets, but they still needed to determine the daily keys for the cipher traffic. The Poles would examine the Enigma traffic and use the method of characteristics to determine the six permutations used for the indicator. The Poles would then use the grill method to determine the rightmost rotor and its position. That search would be complicated by the plugboard permutation, but that permutation only swapped six pairs of letters – not enough to disrupt the search. The grill method also determined the plugboard wiring. The grill method could also be used to determine the middle and left rotors and their setting (and those tasks were simpler because there was no plugboard), but the Poles eventually compiled a catalogue of the 3×2×26×26=4056 possible Q permutations (reflector and 2 leftmost rotor permutations), so they could just look up the answer.

The only remaining secret of the daily key would be the ring settings, and the Poles would attack that problem with brute force. Most messages would start with the three letters "ANX" (an is German for "to" and the "X" character was used as a space). It may take almost 26×26×26=17576 trials, but that was doable. Once the ring settings were found, the Poles could read the day's traffic.

The Germans made it easy for the Poles in the beginning. The rotor order only changed every quarter, so the Poles would not have to search for the rotor order. Later the Germans changed it every month, but that would not cause much trouble, either. Eventually, the Germans would change the rotor order every day, and late in the war (after Poland had been overrun) the rotor order might be changed during the day.

The Poles kept improving their techniques as the Germans kept improving their security measures.

Invariant cycle lengths and the card catalogue

Rejewski realised that, although the letters in the cycle groups were changed by the plugboard, the number and lengths of the cycles were unaffected—in the example above, six cycle groups with lengths of 9, 9, 3, 3, 1, and 1. He described this invariant structure as the characteristic of the indicator setting.[dubious – discuss] There were only 105,456 possible rotor settings.[53][54] The Poles therefore set about creating a card catalogue of these cycle patterns.[55]

The cycle-length method would avoid using the grill. The card catalogue would index the cycle-length for all starting positions (except for turnovers that occurred while enciphering an indicator). The day's traffic would be examined to discover the cycles in the permutations. The card catalogue would be consulted to find the possible starting positions. There are roughly 1 million possible cycle-length combinations and only 105,456 starting positions. Having found a starting position, the Poles would use an Enigma double to determine the cycles at that starting position without a plugboard. The Poles would then compare those cycles to the cycles with the (unknown) plugboard and solve for the plugboard permutation (a simple substitution cipher). Then the Poles could find the remaining secret of the ring settings with the ANX method.

The problem was compiling the large card catalogue.

Rejewski, in 1934 or 1935, devised a machine to facilitate making the catalogue and called it a cyclometer. This "comprised two sets of rotors... connected by wires through which electric current could run. Rotor N in the second set was three letters out of phase with respect to rotor N in the first set, whereas rotors L and M in the second set were always set the same way as rotors L and M in the first set".[56] Preparation of this catalogue, using the cyclometer, was, said Rejewski, "laborious and took over a year, but when it was ready, obtaining daily keys was a question of [some fifteen] minutes".[57]

However, on 1 November 1937, the Germans changed the Enigma reflector, necessitating the production of a new catalogue—"a task which [says Rejewski] consumed, on account of our greater experience, probably somewhat less than a year's time".[57]

This characteristics method stopped working for German naval Enigma messages on 1 May 1937, when the indicator procedure was changed to one involving special codebooks (see German Navy 3-rotor Enigma below).[58] Worse still, on 15 September 1938 it stopped working for German Army and Luftwaffe messages because operators were then required to choose their own Grundstellung (initial rotor setting) for each message. Although German army message keys would still be double-enciphered, the day's keys would not be double-enciphered at the same initial setting, so the characteristic could no longer be found or exploited.

Perforated sheets

Although the characteristics method no longer worked, the inclusion of the enciphered message key twice gave rise to a phenomenon that the cryptanalyst Henryk Zygalski was able to exploit. Sometimes (about one message in eight) one of the repeated letters in the message key enciphered to the same letter on both occasions. These occurrences were called samiczki[59] (in English, females—a term later used at Bletchley Park).[60][61]

Only a limited number of scrambler settings would give rise to females, and these would have been identifiable from the card catalogue. If the first six letters of the ciphertext were SZVSIK, this would be termed a 1–4 female; if WHOEHS, a 2–5 female; and if ASWCRW, a 3–6 female. The method was called Netz (from Netzverfahren, "net method"), or the Zygalski sheet method as it used perforated sheets that he devised, although at Bletchley Park Zygalski's name was not used for security reasons.[62] About ten females from a day's messages were required for success.

There was a set of 26 of these sheets for each of the six possible sequences wheel orders. Each sheet was for the left (slowest-moving) rotor. The 51×51 matrices on the sheets represented the 676 possible starting positions of the middle and right rotors. The sheets contained about 1000 holes in the positions in which a female could occur.[63] The set of sheets for that day's messages would be appropriately positioned on top of each other in the perforated sheets apparatus. Rejewski wrote about how the device was operated:

When the sheets were superposed and moved in the proper sequence and the proper manner with respect to each other, in accordance with a strictly defined program, the number of visible apertures gradually decreased. And, if a sufficient quantity of data was available, there finally remained a single aperture, probably corresponding to the right case, that is, to the solution. From the position of the aperture one could calculate the order of the rotors, the setting of their rings, and, by comparing the letters of the cipher keys with the letters in the machine, likewise permutation S; in other words, the entire cipher key.[64]

The holes in the sheets were painstakingly cut with razor blades and in the three months before the next major setback, the sets of sheets for only two of the possible six wheel orders had been produced.[65]

Polish bomba

After Rejewski's characteristics method became useless, he invented an electro-mechanical device that was dubbed the bomba kryptologiczna, 'cryptologic bomb'. Each machine contained six sets of Enigma rotors for the six positions of the repeated three-letter key. Like the Zygalski sheet method, the bomba relied on the occurrence of females, but required only three instead of about ten for the sheet method. Six bomby[66] were constructed, one for each of the then possible wheel orders. Each bomba conducted an exhaustive (brute-force) analysis of the 17,576[67] possible message keys.

Rejewski has written about the device:

The bomb method, invented in the autumn of 1938, consisted largely in the automation and acceleration of the process of reconstructing daily keys. Each cryptologic bomb (six were built in Warsaw for the Biuro Szyfrów Cipher Bureau before September 1939) essentially constituted an electrically powered aggregate of six Enigmas. It took the place of about one hundred workers and shortened the time for obtaining a key to about two hours.[68]

The cipher message transmitted the Grundstellung in the clear, so when a bomba found a match, it revealed the rotor order, the rotor positions, and the ring settings. The only remaining secret was the plugboard permutation.

Major setback

On 15 December 1938, the German Army increased the complexity of Enigma enciphering by introducing two additional rotors (IV and V). This increased the number of possible wheel orders from 6 to 60.[69] The Poles could then read only the small minority of messages that used neither of the two new rotors. They did not have the resources to commission 54 more bombs or produce 58 sets of Zygalski sheets. Other Enigma users received the two new rotors at the same time. However, until 1 July 1939 the Sicherheitsdienst (SD)—the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party—continued to use its machines in the old way with the same indicator setting for all messages. This allowed Rejewski to reuse his previous method, and by about the turn of the year he had worked out the wirings of the two new rotors.[69] On 1 January 1939, the Germans increased the number of plugboard connections from between five and eight to between seven and ten, which made other methods of decryption even more difficult.[57]

Rejewski wrote, in a 1979 critique of appendix 1, volume 1 (1979), of the official history of British Intelligence in the Second World War:

we quickly found the [wirings] within the [new rotors], but [their] introduction ... raised the number of possible sequences of [rotors] from 6 to 60 ... and hence also raised tenfold the work of finding the keys. Thus the change was not qualitative but quantitative. We would have had to markedly increase the personnel to operate the bombs, to produce the perforated sheets ... and to manipulate the sheets.[70][71]

World War II

Polish disclosures

As the likelihood of war increased in 1939, Britain and France pledged support for Poland in the event of action that threatened its independence.[72] In April, Germany withdrew from the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact of January 1934. The Polish General Staff, realising what was likely to happen, decided to share their work on Enigma decryption with their western allies. Marian Rejewski later wrote:

[I]t was not [as Harry Hinsley suggested, cryptological] difficulties of ours that prompted us to work with the British and French, but only the deteriorating political situation. If we had had no difficulties at all we would still, or even the more so, have shared our achievements with our allies as our contribution to the struggle against Germany.[70][73]

At a conference near Warsaw on 26 and 27 July 1939, the Poles revealed to the French and British that they had broken Enigma and pledged to give each a Polish-reconstructed Enigma, along with details of their Enigma-solving techniques and equipment, including Zygalski's perforated sheets and Rejewski's cryptologic bomb.[74] In return, the British pledged to prepare two full sets of Zygalski sheets for all 60 possible wheel orders.[75] Dilly Knox was a member of the British delegation. He commented on the fragility of the Polish system's reliance on the repetition in the indicator, because it might "at any moment be cancelled".[76] In August, two Polish Enigma doubles were sent to Paris, whence Gustave Bertrand took one to London, handing it to Stewart Menzies of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service at Victoria Station.[77]

Gordon Welchman, who became head of Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, wrote:

Hut 6 Ultra would never have gotten off the ground if we had not learned from the Poles, in the nick of time, the details both of the German military version of the commercial Enigma machine, and of the operating procedures that were in use.[78]

Peter Calvocoressi, who became head of the Luftwaffe section in Hut 3, wrote of the Polish contribution:

The one moot point is—how valuable? According to the best qualified judges it accelerated the breaking of Enigma by perhaps a year. The British did not adopt Polish techniques but they were enlightened by them.[79]

PC Bruno

On 5 September 1939 the Cipher Bureau began preparations to evacuate key personnel and equipment from Warsaw. Soon a special evacuation train, the Echelon F, transported them eastward, then south. By the time the Cipher Bureau was ordered to cross the border into allied Romania on 17 September, they had destroyed all sensitive documents and equipment and were down to a single very crowded truck. The vehicle was confiscated at the border by a Romanian officer, who separated the military from the civilian personnel. Taking advantage of the confusion, the three mathematicians ignored the Romanian's instructions. They anticipated that in an internment camp they might be identified by the Romanian security police, in which the German Abwehr and SD had informers.[80]

The mathematicians went to the nearest railroad station, exchanged money, bought tickets, and boarded the first train headed south. After a dozen or so hours, they reached Bucharest, at the other end of Romania. There they went to the British embassy. Told by the British to "come back in a few days", they next tried the French embassy, introducing themselves as "friends of Bolek" (Bertrand's Polish code name) and asking to speak with a French military officer. A French Army colonel telephoned Paris and then issued instructions for the three Poles to be assisted in evacuating to Paris.[80]

On 20 October 1939, at PC Bruno outside Paris, the Polish cryptologists resumed work on German Enigma ciphers, in collaboration with Bletchley Park.[81]

PC Bruno and Bletchley Park worked together closely, communicating via a telegraph line secured by the use of Enigma doubles. In January 1940 Alan Turing spent several days at PC Bruno conferring with his Polish colleagues. He had brought the Poles a full set of Zygalski sheets that had been punched at Bletchley Park by John Jeffreys using Polish-supplied information, and on 17 January 1940, the Poles made the first break into wartime Enigma traffic—that from 28 October 1939.[82] From that time, until the Fall of France in June 1940, 17 per cent of the Enigma keys that were found by the allies were solved at PC Bruno.[83]

Just before opening their 10 May 1940 offensive against the Low Countries and France, the Germans made the feared change in the indicator procedure, discontinuing the duplication of the enciphered message key. This meant that the Zygalski sheet method no longer worked.[84][85] Instead, the cryptanalysts had to rely on exploiting the operator weaknesses described below, particularly the cillies and the Herivel tip.

After the June Franco-German armistice, the Polish cryptological team resumed work in France's southern Free Zone,[86] although probably not on Enigma.[87] Marian Rejewski and Henryk Zygalski, after many travails, perilous journeys, and Spanish imprisonment, finally made it to Britain,[88] where they were inducted into the Polish Army and put to work breaking German SS and SD hand ciphers at a Polish signals facility in Boxmoor. Due to their having been in occupied France, it was thought too risky to invite them to work at Bletchley Park.[89]

After the German occupation of Vichy France, several of those who had worked at PC Bruno were captured by the Germans. Despite the dire circumstances in which some of them were held, none betrayed the secret of Enigma's decryption.[90]

Operating shortcomings

Apart from some less-than-ideal inherent characteristics of the Enigma, in practice the system's greatest weakness was the large numbers of messages and some ways that Enigma was used. The basic principle of this sort of enciphering machine is that it should deliver a stream of transformations that are difficult for a cryptanalyst to predict. Some of the instructions to operators, and operator sloppiness, had the opposite effect. Without these operating shortcomings, Enigma would almost certainly not have been broken.[91]

The shortcomings that Allied cryptanalysts exploited included:

- The production of an early Enigma training manual containing an example of plaintext and its genuine ciphertext, together with the relevant message key. When Rejewski was given this in December 1932, it "made [his reconstruction of the Enigma machine] somewhat easier".[84]

- Repetition of the message key as described in Rejewski's characteristics method, above. (This helped in Rejewski's solving Enigma's wiring in 1932, and was continued until May 1940.)

- Repeatedly using the same stereotypical expressions in messages, an early example of what Bletchley Park would later term cribs. Rejewski wrote that "... we relied on the fact that the greater number of messages began with the letters ANX—German for "to", followed by X as a spacer".[92]

- The use of easily guessed keys such as AAA or BBB, or sequences that reflected the layout of the Enigma keyboard, such as "three [typing] keys that stand next to each other [o]r diagonally [from each other]..."[93] At Bletchley Park such occurrences were called cillies.[94][95] Cillies in the operation of the four-rotor Abwehr Enigma included four-letter names and German obscenities. Sometimes, with multi-part messages, the operator would not enter a key for a subsequent part of a message, merely leaving the rotors as they were at the end of the previous part, to become the message key for the next part.[96]

- Having only three different rotors for the three positions in the scrambler. (This continued until December 1938, when it was increased to five and then eight for naval traffic in 1940.)

- Using only six plugboard leads, leaving 14 letters unsteckered. (This continued until January 1939 when the number of leads was increased, leaving only a small number of letters unsteckered.)

Other useful shortcomings that were discovered by the British and later the American cryptanalysts included the following, many of which depended on frequent solving of a particular network:

- The practice of re-transmitting a message in an identical, or near-identical, form on different cipher networks. If a message was transmitted using both a low-level cipher that Bletchley Park broke by hand, and Enigma, the decrypt provided an excellent crib for Enigma decipherment.[97]

- For machines where there was a choice of more rotors than there were slots for them, a rule on some networks stipulated that no rotor should be in the same slot in the scrambler as it had been for the immediately preceding configuration. This reduced the number of wheel orders that had to be tried.[98]

- Not allowing a wheel order to be repeated on a monthly setting sheet. This meant that when the keys were being found on a regular basis, economies in excluding possible wheel orders could be made.[99]

- The stipulation, for Air Force operators, that no letter should be connected on the plugboard to its neighbour in the alphabet. This reduced the problem of identifying the plugboard connections and was automated in some Bombes with a Consecutive Stecker Knock-Out (CSKO) device.[100]

- The sloppy practice that John Herivel anticipated soon after his arrival at Bletchley Park in January 1940. He thought about the practical actions that an Enigma operator would have to make, and the short cuts he might employ. He thought that, after setting the alphabet rings to the prescribed setting, and closing the lid, the operator might not turn the rotors by more than a few places in selecting the first part of the indicator. Initially this did not seem to be the case, but after the changes of May 1940, what became known as the Herivel tip proved to be most useful.[94][101][102]

- The practice of re-using some of the columns of wheel orders, ring settings, or plugboard connections from previous months. The resulting analytical short-cut was christened at Bletchley Park Parkerismus after Reg Parker, who had, through his meticulous record-keeping, spotted this phenomenon.[103]

- The re-use of a permutation in the German Air Force METEO code as the Enigma stecker permutation for the day.[104]

Mavis Lever, a member of Dilly Knox's team, recalled an occasion when there was an unusual message, from the Italian Navy, whose exploitation led to the British victory at the Battle of Cape Matapan.

The one snag with Enigma of course is the fact that if you press A, you can get every other letter but A. I picked up this message and—one was so used to looking at things and making instant decisions—I thought: 'Something's gone. What has this chap done? There is not a single L in this message.' My chap had been told to send out a dummy message and he had just had a fag [cigarette] and pressed the last key on the keyboard, the L. So that was the only letter that didn't come out. We had got the biggest crib we ever had, the encypherment was LLLL, right through the message and that gave us the new wiring for the wheel [rotor]. That's the sort of thing we were trained to do. Instinctively look for something that had gone wrong or someone who had done something silly and torn up the rule book.[105]

Postwar debriefings of German cryptographic specialists, conducted as part of project TICOM, tend to support the view that the Germans were well aware that the un-steckered Enigma was theoretically solvable, but thought that the steckered Enigma had not been solved.[4]

Crib-based decryption

The term crib was used at Bletchley Park to denote any known plaintext or suspected plaintext at some point in an enciphered message.

Britain's Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), before its move to Bletchley Park, had realised the value of recruiting mathematicians and logicians to work in codebreaking teams. Alan Turing, a Cambridge University mathematician with an interest in cryptology and in machines for implementing logical operations—and who was regarded by many as a genius—had started work for GC&CS on a part-time basis from about the time of the Munich Crisis in 1938.[106] Gordon Welchman, another Cambridge mathematician, had also received initial training in 1938,[107] and they both reported to Bletchley Park on 4 September 1939, the day after Britain declared war on Germany.

Most of the Polish success had relied on the repetition within the indicator. But as soon as Turing moved to Bletchley Park—where he initially joined Dilly Knox in the research section—he set about seeking methods that did not rely on this weakness, as they correctly anticipated that the German Army and Air Force might follow the German Navy in improving their indicator system.

The Poles had used an early form of crib-based decryption in the days when only six leads were used on the plugboard.[58] The technique became known as the Forty Weepy Weepy method for the following reason. When a message was a continuation of a previous one, the plaintext would start with FORT (from Fortsetzung, meaning "continuation") followed by the time of the first message given twice bracketed by the letter Y. At this time numerals were represented by the letters on the top row of the Enigma keyboard. So, "continuation of message sent at 2330" was represented as FORTYWEEPYYWEEPY.

| Q | W | E | R | T | Z | U | I | O | P |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

Cribs were fundamental to the British approach to solving Enigma keys, but guessing the plaintext for a message was a highly skilled business. So in 1940 Stuart Milner-Barry set up a special Crib Room in Hut 8.[108][109]

Foremost among the knowledge needed for identifying cribs was the text of previous decrypts. Bletchley Park maintained detailed indexes[110] of message preambles, of every person, of every ship, of every unit, of every weapon, of every technical term, and of repeated phrases such as forms of address and other German military jargon.[111] For each message the traffic analysis recorded the radio frequency, the date and time of intercept, and the preamble—which contained the network-identifying discriminant, the time of origin of the message, the callsign of the originating and receiving stations, and the indicator setting. This allowed cross referencing of a new message with a previous one.[112] Thus, as Derek Taunt, another Cambridge mathematician-cryptanalyst wrote, the truism that "nothing succeeds like success" is particularly apposite here.[99]

Stereotypical messages included Keine besonderen Ereignisse (literally, "no special occurrences"—perhaps better translated as "nothing to report"),[113] An die Gruppe ("to the group")[114] and a number that came from weather stations such as weub null seqs null null ("weather survey 0600"). This was actually rendered as WEUBYYNULLSEQSNULLNULL. The word WEUB being short for Wetterübersicht, YY was used as a separator, and SEQS was common abbreviation of sechs (German for "six").[115] As another example, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's Quartermaster started all of his messages to his commander with the same formal introduction.[116]

With a combination of probable plaintext fragment and the fact that no letter could be enciphered as itself, a corresponding ciphertext fragment could often be tested by trying every possible alignment of the crib against the ciphertext, a procedure known as crib-dragging. This, however, was only one aspect of the processes of solving a key. Derek Taunt has written that the three cardinal personal qualities that were in demand for cryptanalysis were (1) a creative imagination, (2) a well-developed critical faculty, and (3) a habit of meticulousness.[117] Skill at solving crossword puzzles was famously tested in recruiting some cryptanalysts. This was useful in working out plugboard settings when a possible solution was being examined. For example, if the crib was the word WETTER (German for "weather") and a possible decrypt before the plugboard settings had been discovered, was TEWWER, it is easy to see that T with W are stecker partners.[118] These examples, although illustrative of the principles, greatly over-simplify the cryptanalysts' tasks.

A fruitful source of cribs was re-encipherments of messages that had previously been decrypted either from a lower-level manual cipher or from another Enigma network.[119] This was called a kiss and happened particularly with German naval messages being sent in the dockyard cipher and repeated verbatim in an Enigma cipher. One German agent in Britain, Nathalie Sergueiew, code named Treasure, who had been 'turned' to work for the Allies, was very verbose in her messages back to Germany, which were then re-transmitted on the Abwehr Enigma network. She was kept going by MI5 because this provided long cribs, not because of her usefulness as an agent to feed incorrect information to the Abwehr.[120]

Occasionally, when there was a particularly urgent need to solve German naval Enigma keys, such as when an Arctic convoy was about to depart, mines would be laid by the RAF in a defined position, whose grid reference in the German naval system did not contain any of the words (such as sechs or sieben) for which abbreviations or alternatives were sometimes used.[121] The warning message about the mines and then the "all clear" message, would be transmitted both using the dockyard cipher and the U-boat Enigma network. This process of planting a crib was called gardening.[122]

Although cillies were not actually cribs, the chit-chat in clear that Enigma operators indulged in among themselves often gave a clue as to the cillies that they might generate.[123]

When captured German Enigma operators revealed that they had been instructed to encipher numbers by spelling them out rather than using the top row of the keyboard, Alan Turing reviewed decrypted messages and determined that the word eins ("one") appeared in 90% of messages.[citation needed] Turing automated the crib process, creating the Eins Catalogue, which assumed that eins was encoded at all positions in the plaintext. The catalogue included every possible rotor position for EINS with that day's wheel order and plugboard connections.[124]

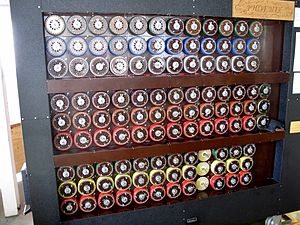

British bombe

The British bombe was an electromechanical device designed by Alan Turing soon after he arrived at Bletchley Park in September 1939. Harold "Doc" Keen of the British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) in Letchworth (35 kilometres (22 mi) from Bletchley) was the engineer who turned Turing's ideas into a working machine—under the codename CANTAB.[125] Turing's specification developed the ideas of the Poles' bomba kryptologiczna but was designed for the much more general crib-based decryption.

The bombe helped to identify the wheel order, the initial positions of the rotor cores, and the stecker partner of a specified letter. This was achieved by examining all 17,576 possible scrambler positions for a set of wheel orders on a comparison between a crib and the ciphertext, so as to eliminate possibilities that contradicted the Enigma's known characteristics. In the words of Gordon Welchman "the task of the bombe was simply to reduce the assumptions of wheel order and scrambler positions that required 'further analysis' to a manageable number".[109]

The demountable drums on the front of the bombe were wired identically to the connections made by Enigma's different rotors. Unlike them, however, the input and output contacts for the left-hand and the right-hand sides were separate, making 104 contacts between each drum and the rest of the machine.[126] This allowed a set of scramblers to be connected in series by means of 26-way cables. Electrical connections between the rotating drums' wiring and the rear plugboard were by means of metal brushes. When the bombe detected a scrambler position with no contradictions, it stopped and the operator would note the position before restarting it.

Although Welchman had been given the task of studying Enigma traffic call signs and discriminants, he knew from Turing about the bombe design and early in 1940, before the first pre-production bombe was delivered, he showed him an idea to increase its effectiveness.[127] It exploited the reciprocity in plugboard connections, to reduce considerably the number of scrambler settings that needed to be considered further. This became known as the diagonal board and was subsequently incorporated to great effect in all the bombes.[21][128]

A cryptanalyst would prepare a crib for comparison with the ciphertext. This was a complicated and sophisticated task, which later took the Americans some time to master. As well as the crib, a decision as to which of the many possible wheel orders could be omitted had to be made. Turing's Banburismus was used in making this major economy. The cryptanalyst would then compile a menu which specified the connections of the cables of the patch panels on the back of the machine, and a particular letter whose stecker partner was sought. The menu reflected the relationships between the letters of the crib and those of the ciphertext. Some of these formed loops (or closures as Turing called them) in a similar way to the cycles that the Poles had exploited.

The reciprocal nature of the plugboard meant that no letter could be connected to more than one other letter. When there was a contradiction of two different letters apparently being stecker partners with the letter in the menu, the bombe would detect this, and move on. If, however, this happened with a letter that was not part of the menu, a false stop could occur. In refining down the set of stops for further examination, the cryptanalyst would eliminate stops that contained such a contradiction. The other plugboard connections and the settings of the alphabet rings would then be worked out before the scrambler positions at the possible true stops were tried out on Typex machines that had been adapted to mimic Enigmas. All the remaining stops would correctly decrypt the crib, but only the true stop would produce the correct plaintext of the whole message.[129]

To avoid wasting scarce bombe time on menus that were likely to yield an excessive number of false stops, Turing performed a lengthy probability analysis (without any electronic aids) of the estimated number of stops per rotor order. It was adopted as standard practice only to use menus that were estimated to produce no more than four stops per wheel order. This allowed an 8-letter crib for a 3-closure menu, an 11-letter crib for a 2-closure menu, and a 14-letter crib for a menu with only one closure. If there was no closure, at least 16 letters were required in the crib.[129] The longer the crib, however, the more likely it was that turn-over of the middle rotor would have occurred.

The production model 3-rotor bombes contained 36 scramblers arranged in three banks of twelve. Each bank was used for a different wheel order by fitting it with the drums that corresponded to the Enigma rotors being tested. The first bombe was named Victory and was delivered to Bletchley Park on 18 March 1940. The next one, which included the diagonal board, was delivered on 8 August 1940. It was referred to as a spider bombe and was named Agnus Dei which soon became Agnes and then Aggie. The production of British bombes was relatively slow at first, with only five bombes being in use in June 1941, 15 by the year end,[130] 30 by September 1942, 49 by January 1943[131] but eventually 210 at the end of the war.

A refinement that was developed for use on messages from those networks that disallowed the plugboard (Stecker) connection of adjacent letters, was the Consecutive Stecker Knock Out. This was fitted to 40 bombes and produced a useful reduction in false stops.[132]

Initially the bombes were operated by ex-BTM servicemen, but in March 1941 the first detachment of members of the Women's Royal Naval Service (known as Wrens) arrived at Bletchley Park to become bombe operators. By 1945 there were some 2,000 Wrens operating the bombes.[133] Because of the risk of bombing, relatively few of the bombes were located at Bletchley Park. The largest two outstations were at Eastcote (some 110 bombes and 800 Wrens) and Stanmore (some 50 bombes and 500 Wrens). There were also bombe outstations at Wavendon, Adstock, and Gayhurst. Communication with Bletchley Park was by teleprinter links.

When the German Navy started using 4-rotor Enigmas, about sixty 4-rotor bombes were produced at Letchworth, some with the assistance of the General Post Office.[134] The NCR-manufactured US Navy 4-rotor bombes were, however, very fast and the most successful. They were extensively used by Bletchley Park over teleprinter links (using the Combined Cipher Machine) to OP-20-G[135] for both 3-rotor and 4-rotor jobs.[136]

Luftwaffe Enigma

Although the German army, SS, police, and railway all used Enigma with similar procedures, it was the Luftwaffe (Air Force) that was the first and most fruitful source of Ultra intelligence during the war. The messages were decrypted in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park and turned into intelligence reports in Hut 3.[137] The network code-named 'Red' at Bletchley Park was broken regularly and quickly from 22 May 1940 until the end of hostilities. Indeed, the Air Force section of Hut 3 expected the new day's Enigma settings to have been established in Hut 6 by breakfast time. The relative ease of solving this network's settings was a product of plentiful cribs and frequent German operating mistakes.[138] Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring was known to use it for trivial communications, including informing squadron commanders to make sure the pilots he was going to decorate had been properly deloused. Such messages became known as "Göring funnies" to the staff at Bletchley Park.[citation needed]

Abwehr Enigma

Dilly Knox's last great cryptanalytical success, before his untimely death in February 1943, was the solving of the Abwehr Enigma in 1941. Intercepts of traffic which had an 8-letter indicator sequence before the usual 5-letter groups led to the suspicion that a 4-rotor machine was being used.[139] The assumption was correctly made that the indicator consisted of a 4-letter message key enciphered twice. The machine itself was similar to a Model G Enigma, with three conventional rotors, though it did not have a plug board. The principal difference to the model G was that it was equipped with a reflector that was advanced by the stepping mechanism once it had been set by hand to its starting position (in all other variants, the reflector was fixed). Collecting a set of enciphered message keys for a particular day allowed cycles (or boxes as Knox called them) to be assembled in a similar way to the method used by the Poles in the 1930s.[140]

Knox was able to derive, using his buttoning up procedure,[34] some of the wiring of the rotor that had been loaded in the fast position on that day. Progressively he was able to derive the wiring of all three rotors. Once that had been done, he was able to work out the wiring of the reflector.[140] Deriving the indicator setting for that day was achieved using Knox's time-consuming rodding procedure.[35] This involved a great deal of trial and error, imagination, and crossword puzzle-solving skills, but was helped by cillies.

The Abwehr was the intelligence and counter-espionage service of the German High Command. The spies that it placed in enemy countries used a lower level cipher (which was broken by Oliver Strachey's section at Bletchley Park) for their transmissions. However, the messages were often then re-transmitted word-for-word on the Abwehr's internal Enigma networks, which gave the best possible crib for deciphering that day's indicator setting. Interception and analysis of Abwehr transmissions led to the remarkable state of affairs that allowed MI5 to give a categorical assurance that all the German spies in Britain were controlled as double agents working for the Allies under the Double Cross System.[120]

German Army Enigma

In the summer of 1940 following the Franco-German armistice, most Army Enigma traffic was travelling by land lines rather than radio and so was not available to Bletchley Park. The air Battle of Britain was crucial, so it was not surprising that the concentration of scarce resources was on Luftwaffe and Abwehr traffic. It was not until early in 1941 that the first breaks were made into German Army Enigma traffic, and it was the spring of 1942 before it was broken reliably, albeit often with some delay.[141] It is unclear whether the German Army Enigma operators made deciphering more difficult by making fewer operating mistakes.[142]

German Naval Enigma

The German Navy used Enigma in the same way as the German Army and Air Force until 1 May 1937 when they changed to a substantially different system. This used the same sort of setting sheet but, importantly, it included the ground key for a period of two, sometimes three days. The message setting was concealed in the indicator by selecting a trigram from a book (the Kenngruppenbuch, or K-Book) and performing a bigram substitution on it.[143] This defeated the Poles, although they suspected some sort of bigram substitution.

The procedure for the naval sending operator was as follows. First they selected a trigram from the K-Book, say YLA. They then looked in the appropriate columns of the K-Book and selected another trigram, say YVT, and wrote it in the boxes at the top of the message form:

| . | Y | V | T |

| Y | L | A | . |

They then filled in the "dots" with any letters, giving say:

| Q | Y | V | T |

| Y | L | A | G |

Finally they looked up the vertical pairs of letters in the Bigram Tables

and wrote down the resultant pairs, UB, LK, RS, and PW which were transmitted as two four letter groups at the start and end of the enciphered message. The receiving operator performed the converse procedure to obtain the message key for setting his Enigma rotors.

As well as these Kriegsmarine procedures being much more secure than those of the German Army and Air Force, the German Navy Enigma introduced three more rotors (VI, VII, and VIII), early in 1940.[144] The choice of three rotors from eight meant that there were a total of 336 possible permutations of rotors and their positions.

Alan Turing decided to take responsibility for German naval Enigma because "no one else was doing anything about it and I could have it to myself".[145] He established Hut 8 with Peter Twinn and two "girls".[146] Turing used the indicators and message settings for traffic from 1–8 May 1937 that the Poles had worked out, and some very elegant deductions to diagnose the complete indicator system. After the messages were deciphered they were translated for transmission to the Admiralty in Hut 4.

German Navy 3-rotor Enigma

The first break of wartime traffic was in December 1939, into signals that had been intercepted in November 1938, when only three rotors and six plugboard leads had been in use.[147] It used "Forty Weepy Weepy" cribs.

A captured German Funkmaat ("radio operator") named Meyer had revealed that numerals were now spelt out as words. EINS, the German for "one", was present in about 90% of genuine German Navy messages. An EINS catalogue was compiled consisting of the encipherment of EINS at all 105,456 rotor settings.[148] These were compared with the ciphertext, and when matches were found, about a quarter of them yielded the correct plaintext. Later this process was automated in Mr Freeborn's section using Hollerith equipment. When the ground key was known, this EINS-ing procedure could yield three bigrams for the tables that were then gradually assembled.[147]

Further progress required more information from German Enigma users. This was achieved through a succession of pinches, the capture of Enigma parts and codebooks. The first of these was on 12 February 1940, when rotors VI and VII, whose wiring was at that time unknown, were captured from the German submarine U-33, by minesweeper HMS Gleaner.

On 26 April 1940, the Narvik-bound German patrol boat VP2623, disguised as a Dutch trawler named Polares, was captured by HMS Griffin. This yielded an instruction manual, codebook sheets, and a record of some transmissions, which provided complete cribs. This confirmed that Turing's deductions about the trigram/bigram process were correct and allowed a total of six days' messages to be broken, the last of these using the first of the bombes.[147] However, the numerous possible rotor sequences, together with a paucity of usable cribs, made the methods used against the Army and Air Force Enigma messages of very limited value with respect to the Navy messages.

At the end of 1939, Turing extended the clock method invented by the Polish cryptanalyst Jerzy Różycki. Turing's method became known as "Banburismus". Turing said that at that stage "I was not sure that it would work in practice, and was not in fact sure until some days had actually broken".[149] Banburismus used large cards printed in Banbury (hence the Banburismus name) to discover correlations and a statistical scoring system to determine likely rotor orders (Walzenlage) to be tried on the bombes. The practice conserved scarce bombe time and allowed more messages to be attacked. In practice, the 336 possible rotor orders could be reduced to perhaps 18 to be run on the bombes.[150] Knowledge of the bigrams was essential for Banburismus, and building up the tables took a long time. This lack of visible progress led to Frank Birch, head of the Naval Section, to write on 21 August 1940 to Edward Travis, Deputy Director of Bletchley Park:

"I'm worried about Naval Enigma. I've been worried for a long time, but haven't liked to say as much... Turing and Twinn are like people waiting for a miracle, without believing in miracles..."[151]

Schemes for capturing Enigma material were conceived including, in September 1940, Operation Ruthless by Lieutenant Commander Ian Fleming (author of the James Bond novels). When this was cancelled, Birch told Fleming that "Turing and Twinn came to me like undertakers cheated of a nice corpse..."[152]

A major advance came through Operation Claymore, a commando raid on the Lofoten Islands on 4 March 1941. The German armed trawler Krebs was captured, including the complete Enigma keys for February, but no bigram tables or K-book. However, the material was sufficient to reconstruct the bigram tables by "EINS-ing", and by late March they were almost complete.[153]

Banburismus then started to become extremely useful. Hut 8 was expanded and moved to 24-hour working, and a crib room was established. The story of Banburismus for the next two years was one of improving methods, of struggling to get sufficient staff, and of a steady growth in the relative and absolute importance of cribbing as the increasing numbers of bombes made the running of cribs ever faster.[154] Of value in this period were further "pinches" such as those from the German weather ships München and Lauenburg and the submarines U-110 and U-559.

Despite the introduction of the 4-rotor Enigma for Atlantic U-boats, the analysis of traffic enciphered with the 3-rotor Enigma proved of immense value to the Allied navies. Banburismus was used until July 1943, when it became more efficient to use the many more bombes that had become available.

M4 (German Navy 4-rotor Enigma)

On 1 February 1942, the Enigma messages to and from Atlantic U-boats, which Bletchley Park called "Shark", became significantly different from the rest of the traffic, which they called "Dolphin".[155]

This was because a new Enigma version had been brought into use. It was a development of the 3-rotor Enigma with the reflector replaced by a thin rotor and a thin reflector. Eventually, there were two fourth-position rotors that were called Beta and Gamma and two thin reflectors, Bruno and Caesar, which could be used in any combination. These rotors were not advanced by the rotor to their right, in the way that rotors I through VIII were.

The introduction of the fourth rotor did not catch Bletchley Park by surprise, because captured material dated January 1941 had made reference to its development as an adaptation of the 3-rotor machine, with the fourth rotor wheel to be a reflector wheel.[156] Indeed, because of operator errors, the wiring of the new fourth rotor had already been worked out.

This major challenge could not be met by using existing methods and resources for a number of reasons.

- The work on the Shark cipher would have to be independent of the continuing work on messages in the Dolphin cipher.

- Solving Shark keys on 3-rotor bombes would have taken 50 to 100 times as long as an average Air Force or Army job.

- U-boat cribs at this time were extremely poor.[157]

It seemed, therefore, that effective, fast, 4-rotor bombes were the only way forward. This was an immense problem and it gave a great deal of trouble. Work on a high speed machine had been started by Wynn-Williams of the TRE late in 1941 and some nine months later Harold Keen of BTM started work independently. Early in 1942, Bletchley Park were a long way from possessing a high speed machine of any sort.[158]

Eventually, after a long period of being unable to decipher U-boat messages, a source of cribs was found. This was the Kurzsignale (short signals), a code which the German navy used to minimise the duration of transmissions, thereby reducing the risk of being located by high-frequency direction finding techniques. The messages were only 22 characters long and were used to report sightings of possible Allied targets.[159] A copy of the code book had been captured from U-110 on 9 May 1941. A similar coding system was used for weather reports from U-boats, the Wetterkurzschlüssel, (Weather Short Code Book). A copy of this had been captured from U-559 on 29 or 30 October 1942.[160] These short signals had been used for deciphering 3-rotor Enigma messages and it was discovered that the new rotor had a neutral position at which it, and its matching reflector, behaved just like a 3-rotor Enigma reflector. This allowed messages enciphered at this neutral position to be deciphered by a 3-rotor machine, and hence deciphered by a standard bombe. Deciphered Short Signals provided good material for bombe menus for Shark.[161] Regular deciphering of U-boat traffic restarted in December 1942.[162]

Italian naval Enigma

In 1940 Dilly Knox wanted to establish whether the Italian Navy were still using the same system that he had cracked during the Spanish Civil War; he instructed his assistants to use rodding to see whether the crib PERX (per being Italian for "for" and X being used to indicate a space between words) worked for the first part of the message. After three months there was no success, but Mavis Lever, a 19-year-old student, found that rodding produced PERS for the first four letters of one message. She then (against orders) tried beyond this and obtained PERSONALE (Italian for "personal"). This confirmed that the Italians were indeed using the same machines and procedures.[35]

The subsequent breaking of Italian naval Enigma ciphers led to substantial Allied successes. The cipher-breaking was disguised by sending a reconnaissance aircraft to the known location of a warship before attacking it, so that the Italians assumed that this was how they had been discovered. The Royal Navy's victory at the Battle of Cape Matapan in March 1941 was considerably helped by Ultra intelligence obtained from Italian naval Enigma signals.

American bombes

Unlike the situation at Bletchley Park, the United States armed services did not share a combined cryptanalytical service. Before the US joined the war, there was collaboration with Britain, albeit with a considerable amount of caution on Britain's side because of the extreme importance of Germany and her allies not learning that its codes were being broken. Despite some worthwhile collaboration among the cryptanalysts, their superiors took some time to achieve a trusting relationship in which both British and American bombes were used to mutual benefit.

In February 1941, Captain Abraham Sinkov and Lieutenant Leo Rosen of the US Army, and Lieutenants Robert Weeks and Prescott Currier of the US Navy, arrived at Bletchley Park, bringing, among other things, a replica of the 'Purple' cipher machine for Bletchley Park's Japanese section in Hut 7.[163] The four returned to America after ten weeks, with a naval radio direction finding unit and many documents,[164] including a "paper Enigma".[165]

The main American response to the 4-rotor Enigma was the US Navy bombe, which was manufactured in much less constrained facilities than were available in wartime Britain. Colonel John Tiltman, who later became Deputy Director at Bletchley Park, visited the US Navy cryptanalysis office (OP-20-G) in April 1942 and recognised America's vital interest in deciphering U-boat traffic. The urgent need, doubts about the British engineering workload, and slow progress prompted the US to start investigating designs for a Navy bombe, based on the full blueprints and wiring diagrams received by US Navy Lieutenants Robert Ely and Joseph Eachus at Bletchley Park in July 1942.[166][167] Funding for a full, $2 million, Navy development effort was requested on 3 September 1942 and approved the following day.

Commander Edward Travis, Deputy Director and Frank Birch, Head of the German Naval Section travelled from Bletchley Park to Washington in September 1942. With Carl Frederick Holden, US Director of Naval Communications they established, on 2 October 1942, a UK:US accord which may have "a stronger claim than BRUSA to being the forerunner of the UKUSA Agreement", being the first agreement "to establish the special Sigint relationship between the two countries", and "it set the pattern for UKUSA, in that the United States was very much the senior partner in the alliance".[168] It established a relationship of "full collaboration" between Bletchley Park and OP-20-G.[169]

An all electronic solution to the problem of a fast bombe was considered,[170] but rejected for pragmatic reasons, and a contract was let with the National Cash Register Corporation (NCR) in Dayton, Ohio. This established the United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory. Engineering development was led by NCR's Joseph Desch, a brilliant inventor and engineer. He had already been working on electronic counting devices.[171]

Alan Turing, who had written a memorandum to OP-20-G (probably in 1941),[172] was seconded to the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington in December 1942, because of his exceptionally wide knowledge about the bombes and the methods of their use. He was asked to look at the bombes that were being built by NCR and at the security of certain speech cipher equipment under development at Bell Labs.[173] He visited OP-20-G, and went to NCR in Dayton on 21 December. He was able to show that it was not necessary to build 336 Bombes, one for each possible rotor order, by utilising techniques such as Banburismus.[174] The initial order was scaled down to 96 machines.

The US Navy bombes used drums for the Enigma rotors in much the same way as the British bombes, but were very much faster. The first machine was completed and tested on 3 May 1943. Soon these bombes were more available than the British bombes at Bletchley Park and its outstations, and as a consequence they were put to use for Hut 6 as well as Hut 8 work.[175] A total of 121 Navy bombes were produced.[176]