Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient

| Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient | |

|---|---|

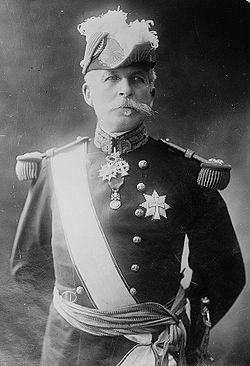

Albert d'Amade, the CEO's first commander | |

| Active | 1915–1916 |

| Country | |

| Role | Expeditionary force |

| Size | 1–2 divisions |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Albert d'Amade Henri Gouraud Maurice Bailloud |

The Corps Expéditionnaire d'Orient (Oriental Expeditionary Force) (CEO) was a French expeditionary force raised for service during the Gallipoli Campaign in World War I. The corps initially consisted of a single infantry division, but later grew to two divisions. It took part in fighting around Kum Kale, on the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles, at the start of the campaign before being moved to Cape Helles where it fought alongside British formations for the remainder of the campaign. In October 1915, the corps was reduced to one division again and was finally evacuated from the Gallipoli peninsula in January 1916 when it ceased to exist.[1]

Formation

Initially, the force consisted of 16,700 troops organised into one division, made up of two brigades, which included "metropolitan" French, and colonial troops.[2][3][4] The so-called metropolitan units included two battalions of zouaves,[5] mainly recruited from French settlers (Pieds-Noirs) in Algeria and Tunisia, plus one battalion of the Foreign Legion,[6] both troop types associated with the 19th Military District of Metropolitan France, known as the Armee d'Afrique. They were joined by the 175th regiment of French line infantry, its troops provided by the other 18 military districts of (mainland) Metropolitan France. The colonial troops consisted of both West African Tirailleurs Senegalais and white regulars of colonial infantry ("marsouins"), amounting to four and two battalions respectively.[5] The force had a strong divisional artillery, consisting of six field and two mountain batteries,[7][a] but having been raised quickly, it received only limited training as a formation. With only two brigades it was smaller than the British divisions that took part in the campaign,[2] having a strength of 16,762 men.[9]

Later in the campaign, the corps was expanded to include a second division.[10] Supporting Corps troops and additional artillery were subsequently shipped to Gallipoli.[b][12] Four squadrons of cavalry were also present, the unit being renamed as the 8th provisional regiment of Chasseurs d'Afrique on 29 July 1915.[13][14]

Troops assigned to the corps wore varying coloured uniforms, even in combat, in contrast to those worn by some of the other nations which they fought alongside. War correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, writing from Gallipoli, provides this account of a scene around Krithia in May 1915:

"Neither was the picturesque element of colour absent from the scene, as in most modern battles, for amidst the green and yellow of the fields and gardens the dark blue uniforms of the Senegalese, the red trousers of the Zouaves, and the new light blue uniform of the Infantry showed up in pleasant contrast amidst the dull-hued masses of the British brigades."[15]

Operational service

Following the Ottoman Empire's entry into the war on the Central Powers side in late 1914, the Allies began preparations to capture the Dardanelles in order to secure a supply route to Russia.[16] As part of these preparations, the Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient was raised on 22 February 1915[17][18] under the command of General Albert d'Amade, who had previously served in Morocco and the Western Front.[19]

Throughout February and March, Anglo-French naval forces attempted to penetrate the Dardanelles, aided by small landing parties that were put ashore to destroy Ottoman fortifications.[20] Several small-scale operations were undertaken, starting on 19 February, but they were hampered by bad weather which delayed the main attack until 18 March. Entering the straits in broad daylight, the force was heavily engaged by Ottoman shore batteries and following heavy losses from mines and shelling, they were forced to turn back.[21] After this, the Allied strategy to capture the Dardanelles turned towards a large-scale landing.[22]

Hastily formed, after assembling on Lemnos there had been no time for the corps to undertake large-scale training before it was committed to the land campaign.[2] During the initial Allied landing on 25 April, the corps undertook a diversionary landing on the Dardanelles Asiatic coast around Kum Kale, to divert Ottoman forces away from the main landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula,[23] and to disrupt Ottoman artillery that could have fired upon the main landings. The 6th Mixed Colonial Regiment led the division ashore, supported by three battleships and a Russian warship. Part of the first wave was turned back by heavy fire, but the rest managed to get ashore and they proceeded to secure the village and an Ottoman fort. Throughout the course of 26 April, the Ottoman 3rd Division counterattacked, but the following day, having lost over 2,200 killed or wounded, the Ottomans began surrendering to the French in large numbers. Nevertheless, the French were withdrawn shortly afterwards, having lost about 300 killed and 500 wounded.[24][25]

Following this, the French force re-embarked and was landed at Cape Helles, where they took up a position on the right flank around 'S' Beach.[26] On 28 April, the commander of the C.E.O. set up the French headquarters at the old castle situated at Sedd el Bahr. With a strength of 24 companies,[27] they subsequently took part in the First Battle of Krithia on 28 April.[28] In early May, the Ottoman forces launched a heavy counterattack on the Allied positions with a force of over 16,000 men. The attack was beaten back, but the French division suffered heavy casualties – up to 2,000 men – and at the height of the assault some of the Senegalese and Zouaves "broke and ran".[9] As a result, the 2nd Naval Brigade from the British Royal Naval Division, had to take over some of their positions.[29] Reinforcements were brought in, including a second French division, which arrived between 6 and 8 May, although they did not arrive in time to take part in the Second Battle of Krithia, during which the 1st Division attacked towards the Kereves Dere gully, and although they made slow progress they eventually managed to secure the high ground overlooking this position before the attack petered out.[10][30]

D'Amade was replaced as commander of the corps in late May when he was dismissed and recalled to France. He was replaced by General Henri Gouraud.[31] On 4 June, both divisions took part in the Third Battle of Krithia, once again forming the right of the Allied line as part of the effort to take Achi Baba, a high feature that dominated the Allied position.[32] The six French batteries were detached to support the British,[33] while the infantry were tasked with attacking the Haricot Redoubt, overlooking the Kereves Dere spur.[32] Attacking in daylight, but possessing a numerical superiority, the Allies made ground across a broad front, before the French were forced back by an Ottoman counterattack, and suffering 2,000 casualties.[34] Regaining positions on the right, the Ottomans were able to enfilade the British positions and eventually they too were forced back, and the attack ultimately failed.[35] In preparation for the August Offensive, minor attacks continued around Helles, and the French undertook further attacks on the Haricot Redoubt, which they subsequently took on 21 June albeit with heavy casualties.[36] In the four days fighting, from 21 to 25 June, the French suffered over 2,500 killed and wounded.[37]

On 30 June, command of the corps changed again when Gouraud, who had been viewed with considerable respect by the British commander, Ian Hamilton, was wounded while touring the front line to boost the morale of his troops. He was replaced by Maurice Bailloud, who had previously commanded one of the corps' divisions.[38] On 12 July, an allied attack at the centre of the line along Achi Baba Nullah (Bloody Valley), gained very little ground and lost 2,500 casualties out of 7,500 men; the Royal Naval Division had 600 casualties and French losses were 800 men. Ottoman losses were about 9,000 casualties and 600 prisoners.[39]

Corps expéditionnaire des Dardanelles

A period of stalemate followed, and after the August Offensive failed to break the deadlock, the Allied commanders at Gallipoli requested heavy reinforcements. The French initially proposed to send a further four divisions, but following Bulgaria's entry into the war, this was cancelled, and in late September one of the corps' divisions was diverted to Salonika, on the Macedonian front.[40][41] On 24 September, a secret telegram was despatched from the French Minister of War to Bailloud.[42][43][44] He was ordered to prepare a division of the C.E.O. composed exclusively of metropolitan units to be sent to aid Serbia. Bailloud and the reconstituted division commenced embarkation on 30 September.[c][47] The division resumed its nomenclature of 156th Infantry Division, and was no longer referred to as the 2nd Division of the C.E.O. thereafter.[48] At the same time, the 10th (Irish) Division was also shipped from Gallipoli, to counter the threat from Bulgaria.[49]

As the French began to refocus their actions in the Mediterranean around Salonika, the Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient was renamed the "Corps expéditionnaire des Dardanelles" on 4 October.[50][51] Notwithstanding the reduction in troop levels, a total of 21,000 French troops remained on the peninsula to show political support to the British nevertheless.[9] There were 8,599 men in the 12 infantry battalions as at 1 October 1915, according to the first report from the C.E.D.'s new commander.[52][d] The attrition through combat deaths and sickness due to the poor sanitary conditions meant that none of the four infantry regiments had maintained their establishment strength of 120 officers and 3,150 other ranks.[54][55] The corps remained in existence until 6 January 1916[e] when, following the evacuation of French forces from the peninsula, it was subsumed into the larger Army of the Orient serving in Salonika.[17][57]

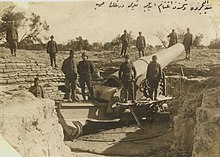

In the autumn of 1915, there were concerns as to the ability of the Senegalese to cope with the winter weather, and their withdrawal from Gallipoli was proposed,[52] once the British agreed to replace them.[58][59] In order to facilitate this, the 57th and 58th regiments were to be composed of Senegalese, with the 54th and 56th composed of Marsouins. This reconstitution took place on 11 December 1915.[60] Similarly, five companies of creoles were detached from the 54th and 56th in order to be sent to a wintering camp. The plan did not go ahead. The creole companies of the 54th were detached on 15 December, and returned to their unit on 22 January 1916.[61] The two locations for the "wintering" were either Egypt or Algeria. For political reasons, it was deemed inappropriate to send them there, but to keep them on Lesbos.[62] It was usual practice for Senegalese to be sent to Fréjus for a period of "wintering" (hivernage),[63] but this location did not get proposed as an alternative, notwithstanding its previous mention by General Joffre.[64] The men of the 58th were evacuated in batches between 16 December and 5 January,[65] whilst the 57th were evacuated by a convoy of several ships on 13 December 1915. The marsouins of the 54th and the 56th were evacuated on 2 and 3 January 1916 respectively.[66] Six older artillery pieces were destroyed and abandoned, two 140 mm guns (modèle 1884) and four 240 mm guns (modèle 1876),[67] given that it was not possible to embark all of the heavy guns.[68][69][70]

At its height, following the deployment of its second division in May, the corps' strength was around 42,000 men.[71][f] Overall, 79,000 men served in the corps throughout the duration of the campaign. Casualties during the campaign amounted to around 47,000 killed, wounded or sick.[71][73][74] Of these, 27,169 were specifically killed, wounded or missing[75] with an implied 20,000 who fell sick.[g] Out of 6,092 missing men, less than one percent were taken prisoner. There is a sole French cemetery on the peninsula, situated to the north of Morto Bay. Veterans were eligible for the Dardanelles campaign medal that was authorised on 15 June 1926.[76]

Order of battle

1st Division (renamed as fr:17e division d'infanterie coloniale on 6 January 1916[78]) under Jean-Marie Brulard

- 1st Metropolitan Brigade[h]

- 2nd Colonial Brigade

- Divisional Troops

- Groupe Holtzapfel – 3 batteries (4x 75mm field guns apiece) of the 1st Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Major Holtzapfel

- Groupe Charpy – 3 batteries (4x 75mm field guns apiece) of the 8th Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Major Charpy

- Groupe Benedittini – 2 batteries (4x 65 mm mountain guns apiece) of the 2nd Mountain Artillery Regiment commanded by Major Benedittini (succeeded by Major Grépinet)[h]

- Supporting elements for engineering, logistical and medical services[12]

2nd Division (156th Infantry Division (France)) under Maurice Bailloud, which disembarked in May 1915

- 3rd Metropolitan Brigade[h]

- 176th Regiment

- three battalions of metropolitan infantry

- 2nd Provisional African Regiment

- composed of three Zouave battalions[79]

- 176th Regiment

- 4th Colonial Brigade

- Divisional Troops

- Groupe Deslions – 3 batteries (4x 75mm field guns apiece) of the 17th Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Captain Deslions[k] [h]

- Groupe Mercadier – 3 batteries (4x 75mm field guns apiece) of the 25th Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Captain Mercadier (succeeded by Captain Salin)[k] [h]

- Groupe Roux – 3 batteries (4x 75mm field guns apiece) of the 47th Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Captain Roux (succeeded by Major Mercadier)[k]

- Supporting elements for engineering, logistical and medical services[12]

Corps Troops

- Corps Artillery:

- 1 Heavy Battery of 120 mm field artillery commanded by Captain Delval [h]

- 1 Heavy Battery of 155 mm field artillery

- 1 Heavy Battery of 6x 155 mm howitzers of the 2nd Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Captain Gavois

- 1 Heavy Battery of 6x 155 mm howitzers of the 48th Field Artillery Regiment commanded by Captain Kolyczko [h]

- 1 Siege gun battery of 2x Canon de 240 mm mle 1884 sur affût à échantigolles

- 1 Siege gun battery of 4x 240 mm mle 1876 on a pivoted firing platform

- Battery of naval guns of 2 Canon de 100 mm Modèle 1891 and 2 Canon de 140 sur affut-truc mle 1884[82]

- Corps Cavalry

- 4 squadrons of Chasseurs d'Afrique[12]

- Miscellaneous

- 1 squadron of supply train

- 4 sections to support the Artillery park

- 1 field company of Engineers

- Signallers, comprising two detachments of telegraphists, and one of radio-telegraphy

- 2 detachments of Military Police

- Escadrille MF98T situated at Tenedos airfield[83]

- Rear echelon support units at Mudros base

- Rear echelon support units at Cape Helles base [12]

Notes and citations

Notes

- ^ Appendix 1 of the French official history (AFGG 8,1) has a four page table listing the units of the C.E.O. at its departure on 4 March 1915. Appendix 2 has a four page breakout of the transport vessels and units aboard.[8]

- ^ Appendix 3 of the French official history (AFGG 8,1) has a one page table chronologically listing the units that subsequently joined the C.E.O. at Gallipoli.[11]

- ^ Général de Brigade Pierre Dauvé's 3rd Metropolitan Brigade now came under the command of the 156th Infantry Division. From this brigade, the 176th Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Regiment (of Armée d'Afrique) embarked on 30 September and 1 October respectively.[45] Regarding the troops of Colonel Emmanuel Bertrand Alexis Bulleux's 1st Metropolitan Brigade, the 175th Infantry Regiment set sail on 1 October.[45] The 1st Regiment (of Armée d'Afrique) were dispersed. The 2nd battalion (of Zouaves, commanded by Louis Marie Joseph Petitpas De La Vasselais) and the 3rd battalion (of Foreign Legion, commanded by Élie Jean) embarked on 1 October. The 1st Battalion (of Zouaves, commanded by Jean Louis Urbain Abadie) embarked on 6 October.[46]

- ^ Colonel Pierre Giradon's report to the Minister of War on the Corps expéditionnaire de Dardanelles, dated 4 November 1915, has 16,000 men drawing rations on Gallipoli, and 8,000 on Mudros. Of these, the combat strength is 10,000 rifles and 60 artillery pieces. In this report, he recommends the withdrawal of the unacclimatised Senegalese, prior to, if not before, the 15th December 1915, who are incapable of tolerating a winter in the Dardanelles.[53]

- ^ 'General Birdwood had already been told that the evacuation of the French contingent, other than the guns to be left in British care, must be completed by the 6th January.'[56]

- ^ General Jean César Graziani, as Chief of the General Staff of the French Army, was asked to provide statistical information, in respect of in the Gallipoli and Salonika campaigns, to highlight French participation in these theatres of war to the Russians. The peak strength of the C.E.O. was 950 officers and 41,000 other ranks, of whom 6,792 were of creole or African ethnicity, when the corps had a strength of two divisions. Following the redeployment to Salonika, the remaining division and supporting staff were 600 officers and 22,000 other ranks.[72]

- ^ Appendix 5 of the French official history (AFGG 8,1) has a one page table that not only splits these into subcategory columns but also breaks out the casualties into nine time period rows.[75] For comparative purposes, out of 205,000 British casualties, 115,000 were killed, missing and wounded, 90,000 were evacuated sick.[74]

- ^ a b c d e f g Dispatched in October 1915 from Gallipoli to Salonika with the second division

- ^ The four companies of the Foreign Legion battalion were augmented by a further two companies[77] composed of ethnic Greek volunteers forming the 13th and 14th companies of the provisional regiment.[80]

- ^ a b c d Change of regimental name and number in August 1915. The regimental war diary records that from 16 August 1915, it was no longer designated the 8th Mixed Colonial Regiment, but was henceforth the 58th Colonial Infantry Regiment. The same nomenclature saw the 4th, 6th and 7th become the 54th, 56th and 57th too.[65]

- ^ a b c Dispatched in May 1915 to Gallipoli with the second division [81]

Citations

- ^ Ferreira, Sylvain (8 January 2016). "Janvier 1916 : l'évacuation finale". Dardanelles 1915–2015 LE CORPS EXPÉDITIONNAIRE D’ORIENT (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2020.

The first regiment of the [remaining French] Brigade to withdraw was evacuated on the night of the 1st/2nd January.

- ^ a b c Erickson 2001, p. 1004.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 39.

- ^ War diary CEO 22 February 1915.

- ^ a b Hure 1972, p. 302.

- ^ "Foreign Legion in the Balkans: 1915-1919". foreignlegion.info. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

Here is the detailed history of the French Foreign Legion in the Balkans during the First World War.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, pp. 539–542.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2005, p. 66.

- ^ a b Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, p. 547.

- ^ a b c d e f "Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient (C.E.O.): J.M.O. 22 février-5 mai 1915: 26 N 75/10 – Pièces justicatives 3 avril-16 septembre 1915" (JPG). Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914–1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. images 132 to 136 of 213. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

Ordre de bataille 1 juin 1915 K34

- ^ "8e REGIMENT DE MARCHE DES CHASSEURS D'AFRIQUE HISTOIRE SUCCINCT 1915–1917". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Ferreira, Sylvain (12 December 2015). "Document : une photo rare d'un chasseur d'Afrique". Dardanelles 1915–2015 LE CORPS EXPÉDITIONNAIRE D’ORIENT (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2020.

Only the machine-gun company of this unit was deployed on the front line during the campaign.

- ^ Ashmead-Bartlett 1927, p. 9.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b Cartwright 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 45–49.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Erickson 2001, p. 1008.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 15 & 61.

- ^ a b Broadbent 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 53.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 82.

- ^ Haythornthwaite 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 111.

- ^ Baldwin 1962, pp. 61 and 66.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, pp. 372–376.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, p. 145.

- ^ Telegram dated 24 September 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 367, pp. 596–597

- ^ AFGG 8,1,1 1924, pp. 596–597.

- ^ a b "156e division d'infanterie: J.M.O. 25 septembre 1915–26 novembre 1916 – 26 N 447/1" (JPG). Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914–1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. images 9 to 10 of 235. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient (C.E.O.): Direction des Etapes et des Services [GHQ Administration]: J.M.O. 5 octobre-31 décembre 1915 – 26 N 76/15" (JPG). Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914–1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. image 2 of 21. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Pompé 1924, p. 859.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 376.

- ^ Dutton 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, p. 115.

- ^ a b Report by General Brulard on the general situation of the C.E.D. upon taking command [on 4 October 1915] dated 12 October 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 371, pp. 600–616

- ^ AFGG 8,1,1 1924, pp. 621–625.

- ^ Lodier, Didier (9 December 2017). "Un régiment d'infanterie en 1914, c'est quoi ?". Chtimiste – mon site consacré aux parcours de régiments en 1914–18 (in French). Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Vaubourg, Cédric. "La composition d'un régiment d'infanterie en 1914" (in French). Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 468.

- ^ Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, p. 125.

- ^ See dispatch from French Minister of War to London Military Attaché dated 25 October 1915 and response dated 4 November 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe nos 374 & 375, pp. 619–620

- ^ The British had been asked 'to meet the wishes of the French,[that] the whole of their Senegalese infantry was [to be] withdrawn from the peninsula' Aspinall-Oglander (1932), p.461

- ^ Memorandum by Chief of Staff C.E.D. 'relating to the reconstitution of the 1st and 2nd brigades and the occupation of the front' dated 11 December 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 412, pp. 683–685

- ^ Historique du 54e RIC 1920, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Secret memorandum from French Minister of War to General Joseph Joffre dated 22 December 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 423, pp. 705–706

- ^ Dez, Bastien (2008). "Les tirailleurs " sénégalais " à l'épreuve de l'hiver". Regards sur... la Première Guerre Mondiale 1914 – 1918 (in French). Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Memorandum from General Joseph Joffre to French Minister of War dated 20 December 1915. In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 420, pp. 700–701

- ^ a b "58e régiment d'infanterie coloniale: J.M.O. 16 août 1915–18 septembre 1916 – 26 N 867/14" (JPG). Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914–1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

Also contains the war diary for the 8e régiment mixte colonial from the 2 May to 16 August 1915

- ^ 'On the 1st January the French Colonial brigade was relieved on the right of the line by units of the Royal Naval Division. In the course of the next two nights the last of the French troops, other than the batteries to remain to the end, were embarked by the French fleet.' Aspinall-Oglander (1932), p.470

- ^ AFGG 8,1,1 1924, p. 714.

- ^ 'It was decided to retain and finally destroy one British 6-inch gun and six old heavy French guns which it would be impossible to withdraw on the last night. (General Brulard himself suggested the destruction of these old and nearly worthless guns.)' Aspinall-Oglander (1932), p.469

- ^ Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 465.

- ^ Hart 2020, pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Hughes 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Letter from Graziani to Lavergne dated 15 September 1916. '(Enclosure 1) The French war effort in the Dardanelles from 1 March 1915 to 1 January 1916.' In AFGG 8,1,1 Annexes (1924) Annexe n° 438, p. 728–731

- ^ Erickson 2001, p. 1009.

- ^ a b Aspinall-Oglander 1932, p. 484.

- ^ a b Lepetit, Tournyol du Clos & Rinieri 1923, p. 549.

- ^ "Decree of 15 June 1926" (in French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 17 June 1926. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b Aspinall-Oglander 1932, pp. 494–5.

- ^ Pompé 1924, pp. 991–4.

- ^ a b "Zouaves et Dardanelles". Forum pages14-18 (in French). 12 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Greek infantry at Gallipoli". Great War Forum. 10 December 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Pompé 1924, p. 860.

- ^ "Artillerie et expédition d'Orient". Forum pages14-18 (in French). 5 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

There were no units of Artillerie Coloniale at Gallipoli in 1915

- ^ Ferreira, Sylvain (11 November 2015). "11 mai, l'escadrille MF 98 T est opérationnelle". Dardanelles 1915–2015 LE CORPS EXPÉDITIONNAIRE D’ORIENT (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2020.

As indicated by the initials of the squadron (MF), they were equipped with eight MF.9 aircraft.

References

- Ashmead-Bartlett, Ellis (14 May 1927). "Gallipoli: Story of an Eye-witness War Correspondent's Account. Peeps Behind the Scenes". The Mercury. p. 9.

- Aspinall-Oglander, C. F. (1932). Military Operations Gallipoli, Vol II: May 1915 to the Evacuation. History of the Great War. London: William Heinemann. OCLC 278615923.

- Aspinall-Oglander, C. F., ed. (1992). Military Operations Gallipoli, Vol II: Appendices. History of the Great War. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-946-0.

Twenty appendices essential to understanding the campaign

- Baldwin, Hanson (1962). World War I: An Outline History. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 793915761.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2005). Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore. Camberwell, Victoria: Viking/Penguin. ISBN 0-670-04085-1.

- Cartwright, William (2013). "An Investigation of Maps and Cartographic Artefacts of the Gallipoli Campaign 1915: Military, Commercial and Personal". In Moore, Antoni; Drecki, Igor (eds.). Geospatial Visualisation. New York: Springer. pp. 19–40. ISBN 9783642122897.

- "Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient (C.E.O.): J.M.O. 22 février-5 mai 1915: 26 N 75/1" (JPG). Mémoire des hommes: Journaux des Unites (1914–1918) (in French). Ministere De la Defense. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Dutton, David (1998). The Politics of Diplomacy: Britain, France and the Balkans in the First World War. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860641121.

- Erickson, Edward (2001). "Strength Against Weakness: Ottoman Military Effectiveness at Gallipoli, 1915". The Journal of Military History. 65 (4): 981–1012. doi:10.2307/2677626. ISSN 1543-7795. JSTOR 2677626.

- Hart, Peter (2020). The Gallipoli Evacuation. Sydney: Living History. ISBN 978-0-6489-2260-5. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2004) [1991]. Gallipoli 1915: Frontal Assault on Turkey. Campaign Series #8. London: Osprey. ISBN 0-275-98288-2.

- Historique du 54e régiment d'infanterie coloniale 1914-1918 (in French). Toulon: Imprimerie Barthélemy Bouchet. 1920. FRBNF42716101.

- Hughes, Matthew (2005). "The French Army at Gallipoli". The RUSI Journal. 153 (3): 64–67. doi:10.1080/03071840508522907. ISSN 0307-1847. S2CID 154727404.

- Hure, R. (1972). L'Armee d'Afrique 1830–1962. Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle. OCLC 464095274.

- Lepetit, Vincent; Tournyol du Clos, Alain; Rinieri, Ilario, eds. (1923). La campagne d'Orient (Dardanelles et Salonique) Premier Volume. (février 1915-août 1916) [8,1] Tome VIII. Les armées françaises dans la Grande guerre. Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Ministère De la Guerre, Etat-Major de l'Armée – Service Historique (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. OCLC 491775878.

- La campagne d'Orient jusqu'à l'intervention de la Roumanie (février 1915-août 1916). Annexes – 1er Volume [8,1,1] Tome VIII. Premier volume. Les armées françaises dans la Grande guerre. Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Ministère De la Guerre, Etat-Major de l'Armée – Service Historique (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. 1924. OCLC 163166542. Primary source documents

- Pompé, Daniel; et al., eds. (1924). Ordres de bataille des grandes unités – Divisions d'Infanterie, Divisions de Cavalerie [10,2]. Tome X. 2e Volume. Les armées françaises dans la Grande guerre. Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Ministère De la Guerre, Etat-Major de l'Armée – Service Historique (in French) (1st ed.). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

Further reading

- Cassar, George H. (2019). Reluctant Parner: The Complete Story of the French Participation in the Dardanelles Expedition of 1915. Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911628-92-7.

- Cooper, Augustus Richard (2016). "6 With the Foreign Legion in Gallipoli". In Bilton, Rachel (ed.). In the Trenches: Those Who Were There. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-6715-4.

- Dardanelles, Orient, Levant: 1915–1921 Ce que les combattants ont écrit [Dardanelles, Orient, Levant: 1915–1921 A compendium of veterans' eyewitness accounts] (in French). Preface written by Michèle Alliot-Marie. Paris: Association nationale pour le souvenir des Dardanelles et fronts d'Orient. 2005. ISBN 2-7475-7905-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Ferreira, Sylvain (2015). L'Expédition française aux Dardanelles - Avril 1915 - Janvier 1916. Collection Illustoria. Clermont-Ferrand: Lemme Edit. ISBN 978-2-917575-59-8.

- Jauffret, Jean-Charles [in French] (2000) [1996]. "The Gallipoli Campaign: the French point of view" [L'expédition des Dardanelles vue du côté français]. In Gilbert, Martin (ed.). The Straits of War. The Gallipoli Memorial Lectures 1985–2000. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2408-5.

- Horne, John (2019). "A Colonial Expedition? French Soldiers' Experience at the Dardanelles". War and Society. 38 (4): 286–304. doi:10.1080/07292473.2019.1643493. S2CID 201420971.

- Saint-Ramond, Francine (2019). Les Désorientés: Expériences des soldats français aux Dardanelles et en Macédoine, 1915-1919 (in French). Presses de l’Inalco. ISBN 978-2-85-831299-3.

- Vassal, Joseph (1916). Uncensored Letters from the Dardanelles: Written to His English Wife by a French Medical Officer. Preface written by Albert d'Amade. London: William Heinemann. OCLC 800491901.