Colposcopy

| Colposcopy | |

|---|---|

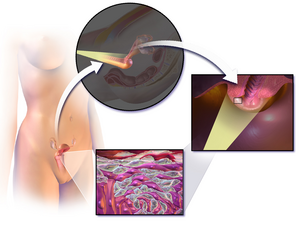

In this diagram, the canal of the cervix (or endocervix) is circled at the base of the womb. The vaginal portion of the cervix projects free into the vagina. The transformation zone, at the opening of the cervix into the vagina, is the area where most abnormal cell changes occur | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology |

| ICD-9-CM | 67 |

| MeSH | D003127 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-671 |

Colposcopy (Ancient Greek: κόλπος, romanized: kolpos, lit. 'hollow, womb, vagina' + skopos 'look at') is a medical diagnostic procedure to visually examine the cervix as well as the vagina and vulva using a colposcope.[1]

The main goal of colposcopy is to prevent cervical cancer by detecting and treating precancerous lesions early. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a common infection and the underlying cause for most cervical cancers. Smoking also makes developing cervical abnormalities more likely.

Other reasons for a patient to have a colposcopy include assessment of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero, immunosuppression, abnormal appearance of the cervix or as a part of a sexual assault forensic examination.

Colposcopy is done using a colposcope, which provides a magnified and illuminated view of the areas, allowing the colposcopist to visually distinguish normal from abnormal appearing tissue, such as damaged or abnormal changes in the tissue (lesions), and take directed biopsies for further pathological examination if needed.

Colposcopy has historical roots in the 10th century when Abulcasis, a renowned Arabian physician, pioneered the use of reflected light to inspect internal organs, with the cervix being the first organ examined in this way.[2][3][4] The modern procedure was developed by the German physician Hans Hinselmann, with help from Eduard Wirths.[5][6] The development of colposcopy involved experimentation on Jewish inmates from Auschwitz.[7]

Indications

Most women undergo a colposcopy to further investigate an abnormal pap test result (cytological).

Other reasons for a patient to have a colposcopy include:

- assessment of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero,

- immunosuppression such as HIV infection, or an organ transplant patient

- an abnormal appearance of the cervix as noted by a primary care provider

- as a part of a sexual assault forensic examination using a specialized colposcope equipped with a camera[8]

Many physicians base their current evaluation and treatment decisions on[citation needed] the report "Evidence-Based Consensus Recommendations for Colposcopy Practice for Cervical Cancer Prevention in the United States", developed by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, most recently in 2017.[9]

Colposcopy is not generally performed for people with pap test results showing low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) or less. SILs are an abnormal growth of epithelial cells, known as a lesion, on the surface of the cervix. Unless the person has a visible lesion, colposcopy for this population does not detect a recurrence of cancer.[10]

Procedure

Type 1: Completely ectocervical (common under hormonal influence).

Type 2: Endocervical component but fully visible (common before puberty).

Type 3: Endocervical component, not fully visible (common after menopause).

During the initial evaluation, a medical history is obtained. The procedure is fully described to the patient. In some cases a pregnancy test may be performed before the procedure and the patient then signs a consent form.[citation needed] Colposcopy is performed with the woman lying back, legs in stirrups, and buttocks at the lower edge of the table (a position known as the dorsal lithotomy position). A speculum is placed in the vagina after the vulva is examined for any suspicious lesions.[citation needed]

A colposcope is used to identify visible clues suggestive of abnormal tissue. It functions as a lighted binocular or monocular microscope to magnify the view of the cervix, vagina, and vulvar surface. [12][13]

Low magnification (2× to 6×) may be used to obtain a general impression of the surface architecture. 8× to 25× magnification are utilized to evaluate the vagina and cervix. High magnification together with green filter is often used to identify certain vascular patterns that may indicate the presence of more advanced pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions.[citation needed]

The squamocolumnar junction, or "transformation zone", is a critical area on the cervix where many precancerous and cancerous lesions most often arise. The ability to see the transformation zone and the entire extent of any lesion visualized determines whether an adequate colposcopic examination is attainable.[citation needed]

Acetic acid solution is applied to the surface of the cervix using cotton swabs to improve visualization of abnormal areas.[citation needed]. Areas of the cervix that turn white (acetowhiteness) after the application of acetic acid or have an abnormal vascular pattern are often considered for biopsy. If no lesions are visible, an iodine solution may be applied to the cervix to help highlight areas of abnormality.[citation needed]

After a complete examination, the colposcopist determines the areas with the highest degree of visible abnormality and may obtain biopsies from these areas using a long biopsy instrument, such as a punch forceps, SpiraBrush CX or SoftBiopsy. Most doctors and patients consider anesthesia unnecessary; however, some colposcopists now recommend and use a topical anesthetic such as lidocaine or a cervical block to decrease patient discomfort, particularly if many biopsy samples are taken.[citation needed]

Following any biopsies, an endocervical curettage (ECC) is often done. The ECC utilizes a long straight curette, a Soft-ECC curette employing fabric to simultaneously collect tissue, or a cytobrush (like a small pipe-cleaner) to scrape the inside of the cervical canal. The ECC should never be done on a patient who is pregnant. Monsel's solution is applied with large cotton swabs to the surface of the cervix to control bleeding. This solution looks like mustard and turns black when exposed to blood. After the procedure this material will be expelled naturally: Patients can expect to have a thin coffee-ground like discharge for up to several days after the procedure. Alternatively, some physicians achieve hemostasis with silver nitrate.[citation needed]

Interpretation

One model for scoring colposcopy findings is the Swede Score, which assigns a score between 0 and 2 for five different parameters, based on what is visible during the colposcopy, as given in table below:

| Parameter | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Uptake of acetic acid |

0 or transparent | Shady, milky | Distinct, stearin-like |

| Margins and surface | 0 or diffuse | Sharp, but irregular, jagged, "geographical" satellites | Sharp and even, difference in surface level such as "cutting" |

| Vessels | Fine, regular | Absent | Coarse or atypical |

| Lesion size | < 5 mm | 5–15 mm or spanning 2 quadrants | > 15 mm or spanning 3–4 quadrants or endocervically undefined |

| Iodine staining | Brown | Faintly or patchy yellow | Distinct yellow |

The total Swede Score ranges between 0 and 10. A score of 5 or above is reported to identify all potential high-grade lesions (HGL) and 8 or above to have a 90% chance of being a HGL.[14] A score below 5 does not require biopsy because of low risk of cancer, a score from 5 to 7 requires biopsy, and a score 8 or above does not require biopsy because it is likely more efficient to intervene directly (e.g., by excision).[14]

Complications

Significant complications from a colposcopy are not common but may include bleeding, infection at the biopsy site or endometrium, and failure to identify the lesion. Monsel's solution and silver nitrate interfere with the interpretation of biopsy specimens, so these substances are not applied until all biopsies have been taken. Some patients experience a degree of discomfort during the curettage, and many experience discomfort during the biopsy.[citation needed]

Colposcopy with biopsy does not cause infertility or subfertility.[15]

Follow up

Adequate follow-up is critical to the success of this procedure. Treatments for significant lesions include ablative treatments (cryotherapy, thermocoagulation, and laser ablation) and excisional methods (loop electrosurgical excision procedure or LEEP, or Cervical conization).[citation needed]

References

- ^ Chase DM, Kalouyan M, DiSaia PJ (May 2009). "Colposcopy to evaluate abnormal cervical cytology in 2008". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 200 (5): 472–80. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.025. PMID 19375565.

- ^ Spaner, S. J.; Warnock, G. L. (1997). "A brief history of endoscopy, laparoscopy, and laparoscopic surgery". Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. Part A. 7 (6): 369–373. doi:10.1089/lap.1997.7.369. ISSN 1092-6429. PMID 9449087.

- ^ Frantizides CT (ed): Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby, 1995.

- ^ Graber IN, Schultz LS, Pietrofitta JJ, Hickok DF (eds): Laparoscopic Abdominal Surgery. Chicago: McGraw-Hill,

- ^ "The Deadly Origins Of A Life-saving Procedure – Forward.com". 27 January 2007. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Baggish, Michael S. (11 April 2018). Colposcopy of the Cervix, Vagina, and Vulva: A Comprehensive Textbook. Mosby. ISBN 9780323018593. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Halioua, Bruno (2010). "The Participation of Hans Hinselman in Medical Experiments at Auschwitz". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 14 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181af30ef. PMID 20040829. S2CID 188116.

- ^ "Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations". Archived from the original on 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ Wentzensen, Nicolas; Massad, L. Stewart; Mayeaux, Edward J.; Khan, Michelle J.; Waxman, Alan G.; Einstein, Mark H.; Conageski, Christine; Schiffman, Mark H.; Gold, Michael A.; Apgar, Barbara S.; Chelmow, David; Choma, Kim K.; Darragh, Teresa M.; Gage, Julia C.; Garcia, Francisco A.R.; Guido, Richard S.; Jeronimo, Jose A.; Liu, Angela; Mathews, Cara A.; Mitchell, Martha M.; Moscicki, Anna-Barbara; Novetsky, Akiva P.; Papasozomenos, Theognosia; Perkins, Rebecca B.; Silver, Michelle I.; Smith, Katie M.; Stier, Elizabeth A.; Tedeschi, Candice A.; Werner, Claudia L.; Huh, Warner K. (2017). "Evidence-Based Consensus Recommendations for Colposcopy Practice for Cervical Cancer Prevention in the United States" (PDF). Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 21 (4): 216–222. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000322. ISSN 1526-0976. PMID 28953109. S2CID 24933665.

- ^ Society of Gynecologic Oncology (February 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, retrieved 19 February 2013, which cites

- Rimel, B. J.; Ferda, A.; Erwin, J.; Dewdney, S. B.; Seamon, L.; Gao, F.; Desimone, C.; Cotney, K. K.; Huh, W.; Massad, L. S. (2011). "Cervicovaginal Cytology in the Detection of Recurrence After Cervical Cancer Treatment". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118 (3): 548–53. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182271fdd. PMID 21860282. S2CID 2465459.

- Tergas, A. I.; Havrilesky, L. J.; Fader, A. N.; Guntupalli, S. R.; Huh, W. K.; Massad, L. S.; Rimel, B. J. (2013). "Cost analysis of colposcopy for abnormal cytology in post-treatment surveillance for cervical cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 130 (3): 421–5. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.037. PMID 23747836.

- ^ International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) classification. References:

-"Transformation zone (TZ) and cervical excision types". Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia.

- Jordan, J.; Arbyn, M.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Schenck, U.; Baldauf, J-J.; Da Silva, D.; Anttila, A.; Nieminen, P.; Prendiville, W. (2008). "European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening: recommendations for clinical management of abnormal cervical cytology, part 1". Cytopathology. 19 (6): 342–354. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.2008.00623.x. ISSN 0956-5507. PMID 19040546. S2CID 16462929. - ^ Kelly M. Pyrek (2006-01-13). Forensic Nursing. CRC Press. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-1-4200-0291-1.

- ^ Margaret M. Stark (2011-09-22). Clinical Forensic Medicine: A Physician's Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-1-61779-258-8.

- ^ a b c Principles and Practice of Colposcopy. JP Medical Ltd. 2011. p. 91. ISBN 9789350250945. Archived from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ^ Spracklen, C. N.; Harland, K. K.; Stegmann, B. J.; Saftlas, A. F. (2013). "Cervical surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and prolonged time to conception of a live birth: A case-control study". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 120 (8): 960–965. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12209. PMC 3691952. PMID 23489374.

External links

- Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Beginner's Manual (IARC Screening Group)

- Atlas of colposcopy – principles and practice (IARC Screening Group)

- American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology

- Women & Babies Colposcopy and gynaecology procedures undertaken by the Women & Babies Consultants.