History of Coventry

Coventry, a city in the West Midlands, England, grew to become one of the most important cities in England during the Middle Ages due to its booming cloth and textiles trade. The city was noted for its part in the English Civil War, and later became an important industrial city during the 19th and 20th centuries, becoming the centre of the British bicycle and later motor industry. The devastating Blitz in 1940 destroyed much of the city centre, and saw its rebuilding during the 1950s and 60s. The motor industry slumped during the 1970s and 80s, and Coventry saw high unemployment. However, in the new millennium the city, along with many others saw significant urban renaissance and in 2017 it was announced that the city had been awarded the title of 2021 UK City of Culture.[1]

Early history

Beginnings

Little is known of the earliest history of Coventry, but prior to its existence there were Celtic settlements in nearby Corley and Baginton, which came to be occupied by the Romans, and later by Saxon invaders.[2] These locations were probably chosen because they lay on early trackways, and were situated on light, easily worked soil free from thick forest and undergrowth; unlike the heavy clay soil, covered in marsh and forest near the north-eastern reaches of the Forest of Arden on which Coventry would rise.[3][4]

In 2020, a portable ogham stone carved between the 4th and 6th centuries AD was unearthed in a Coventry garden. Being only 11cm long and weighing 139g, its Primitive Irish inscription reads MALDUMCAIL/S/LASS (Ogham script: ᚋᚐᚂᚇᚒᚋᚉᚐᚔᚂᚄᚂᚐᚄᚄ), and was therefore in some way related to a Máel Dumcail. The find is unusual in that most Ogham inscriptions of this era are found in Ireland, Wales, and Dumnonia, and it may have been carved by an Irish merchant or mercenary.[5] [6]

The first settlement here grew around a Saxon nunnery which had been founded c. AD 700 by St. Osburga. With the forest being mostly unsuitable for the cultivation of crops, the Saxon settlers would have cleared the land and concentrated on raising cattle and sheep, eventually leading to Coventry's successful wool industry and great wealth.[3] The name "Coventry" would have had its origins at this time and has had several forms of spelling,[7] as well as many theories regarding its meaning, but "Cofa's tree" (also spelt "Coffa's tree") is thought to be a most likely source of the name. Nothing is known of Cofa, but a tree planted by, or named after him may have marked the centre or the boundary of the settlement.[4] An alternative favoured by some is "Coventre" – derived from the words "Coven" (old variation of "Convent") and "tre" (Celtic: "settlement" or "town"), giving rise to "Convent Town".[8]

Origins of St. Mary's Priory and Cathedral

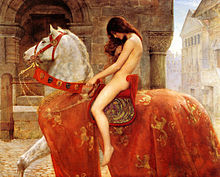

The first chronicled event in the history of Coventry took place in 1016 when King Canute and his army of Danes were laying waste to many towns and villages in Warwickshire in a bid to take control of England, and on reaching the settlement of Coventry they destroyed the Saxon nunnery.[9] Leofric, Earl of Mercia and his wife Lady Godiva (a corruption of her given name, "Godgifu") rebuilt on the remains of the nunnery to found a Benedictine monastery in 1043 dedicated to St. Mary for an abbot and 24 monks.[9][10] Leofric had been appointed Earl by Canute and was one of the three most powerful men in the country, while Godiva was already a woman of high status before marriage and owned much land.[11]

He [Leofric] and his wife, the noble Countess Godgifu, a worshipper of God and devout lover of St Mary ever-virgin, built the monastery there from the foundations out of their own patrimony, and endowed it adequately with lands and made it so rich in various ornaments that in no monastery in England might be found the abundance of gold, silver, gems and precious stones that was at that time in its possession.

Edward the Confessor, who had been crowned king by this time, favoured pious acts of this nature and granted a charter confirming Leofric and Godiva's gift.[9]

According to the popular story,[13][14] Godiva took pity on the people of Coventry, who were suffering grievously under her husband's oppressive taxation. She appealed again and again to her husband, who obstinately refused to remit the tolls. At last, weary of her entreaties, he said he would grant her request if she would strip naked and ride through the streets of the town. Godiva took him at his word and, after issuing a proclamation that all persons should keep within doors and shut their windows, she rode through the town, clothed only in her long hair. In the end, Godiva's husband keeps his word and abolishes the onerous taxes. However, known facts do not corroborate the legend.

Bishop Robert de Limesey transferred his see to Coventry c. 1095, and in 1102 papal authorisation for this move also turned the monastery of St. Mary into a priory and cathedral.[15] The subsequent rebuilding and expansion of St. Mary's was completed about 125 years later.[16]

In February 2000, Channel 4's Time Team archaeologists discovered significant remnants of a major pre-Tudor cathedral/monastery complex (St Mary's) adjacent to the current cathedral, with the team revisiting the excavation site in March 2001.

When the monastery was founded, Leofric gave the northern half of his estates in Coventry to the monks to support them. This was known as the "Prior's-half", and the other was called the "Earl's-half" which would later pass to the Earls of Chester, and explains the early division of Coventry into two parts (until the Royal "Charter of Incorporation" was granted in 1345). In 1250, Roger de Mold (referred to in older documents as "Roger de Montalt"), the earl at the time who had gained his position by marriage, sold his wife's rights and estates in the southern side of Coventry to the Prior, and for the next 95 years the town was controlled by a single "land lord". However, disputes arose between the monastic tenants and those previously of the Earl, and the Prior never gained complete control over Coventry.[17][18]

Coventry's castle

Coventry Castle was originally built towards the end of the 11th century by Ranulph le Meschin, 1st Earl of Chester, but was razed to the ground in the 12th century.[19] It was rebuilt around 1137 to 1140 by Ranulph de Gernon, 2nd Earl of Chester, who successfully held it against King Stephen during the civil war known as The Anarchy ("Barons Wars" or "The Nineteen-Year Winter").[20] Although the exact location of the castle is unknown, Broadgate, Coventry's city centre, refers to the "broad gate" or main approach to the castle which therefore must have been situated in its vicinity.

In time, merchants and tradesmen settled around the monastery and castle, a market was established at the monastery gates, new houses multiplied and two churches were built: Holy Trinity for the tenants of the Prior's-half, and St. Michael's for those living in the Earl's-half. From then on Coventry began to develop a more organised layout; streets appeared and, similar to London and other old cities, trading quarters came into being.[21] Coventry also has some surviving religious artworks from this time, such as the doom painting at Holy Trinity Church which features Christ in judgement, figures of the resurrected, and contrasting images of Heaven and Hell.[22]

Ranulf was succeeded as earl by his rebellious son, Hugh de Kevelioc, 3rd Earl of Chester, who in 1173 held Coventry's castle against King Henry II. Henry sent a strong force to Coventry, which almost certainly severely damaged the castle.[20] Over the years, what remained of the castle fell into disuse and eventually disappeared, and from the 13th century the manor house at Cheylesmore took its place as the earls' residence.[21]

One of the last mentions of the castle was in 1569, following the Catholic Rising of the North: Mary Queen of Scots was rushed south from Tutbury Castle to Coventry.[23][24] Elizabeth I sent a letter, instructing the people of Coventry to look after Mary.[25] She suggested that Mary be held somewhere secure such as Coventry Castle. However, by that time it was too decayed and Mary was instead first held at the Bull Inn, Smithford Street before being moved to the Mayoress's Parlour in St. Mary's Guildhall.[20] Following the defeat of the rebels, Mary was once more sent north to Chatsworth in May 1570.

Growth and prosperity

Coventry may have remained a place of little importance had it not been for the benefaction of Leofric and Godiva in founding the monastery; however, its growth was also assisted by other factors. Running through the town was the River Sherbourne which provided a source of water and power for mills, and there were plentiful supplies of timber nearby for fuel and building purposes. Stone was quarried mainly at nearby Whitley and Cheylesmore and there was good arable land and extensive commons all around Coventry. Its central location and proximity to the old Roman Watling Street and the Fosse Way made it ideally situated for trade.[26]

Early trade and produce

The inhabitants of Coventry themselves influenced the development of the town when between 1150 and 1200 they obtained three charters granted by the Earls of Chester and by Henry II. One of the privileges guaranteed that any merchants coming to the town would be free to trade in peace, and if they wished to settle they would be free of rent and dues for a period of two years from when they began to build. This quickly encouraged the exchange of local produce such as wool, soap, needles, metal and leather goods.[27]

The abundant grazing land around the town, suited to sheep farming and wool production, enabled it to become a centre of many textile trades by the 13th century, especially those related to wool.[28] Coventry's prosperity then rested largely on the dyers who produced "Coventry blue" cloth from woad, which was highly sought after across Europe due to its non-fading qualities, and which is believed to be the origin of the term true blue, i.e. remaining fast or true. According to John Ray in his book A Compleat Collection of English Proverbs (1670):

Coventry had formerly the reputation for dying of blues; insomuch that true blue became a Proverb to signifie one that was always the same and like himself.[29]

This trade was assisted first by a 1273 Crown charter enabling export to "any places beyond the seas", and then by another in 1334 that granted traders freedom from toll and other dues for their merchandise throughout the realm. Then in 1340, permission was given to found a merchant guild to protect and enforce these privileges.[28]

In addition to the previously mentioned early local produce, Coventry also had a small but thriving trade in glass- making and painting as well as tile manufacture,[30] and by the 14th century and throughout the medieval period, Coventry was the fourth largest city in England, with a population of around 10,000; only Norwich, Bristol and London were larger.

City walls

Reflecting Coventry's commercial and strategic importance, in 1355 construction began on city walls, a vast and expensive undertaking funded by local tolls and taxes, and for which King Richard II allowed stone to be quarried from his park in Cheylesmore. The building started at New Gate and was initially finished in around 1400,[31] but much repair work and re-routing was subsequently carried out and its final form was not completed until 1534. They were an impressive feature; measuring nearly 2.2 miles (3.5 km) around and consisting of two red sandstone walls infilled with rubble over 8 feet (2.4 m) thick and 12 feet (3.7 m) high, with 32 towers including 12 gatehouses.[32][33] With its walls, Coventry was described as being the best-defended city in England outside London.[32]

Major buildings

By the 15th century, the size of the city had become more-or-less fixed and its streets and main buildings had largely been completed. Within the city walls were a number of impressive churches: in addition to Holy Trinity, by this time considerably enlarged; and St. Michael's, which had been rebuilt as one of the largest parish churches in England with a magnificent tower and spire; the nearby priory with its cathedral church now dominated the scene and is thought to have possibly had three spires itself.[34] The church of the greyfriars (later Christ Church) also had a spire, while the guild church of St. John the Baptist at Bablake had a short square tower. The Whitefriars or Carmelites had a church not far from the remains of their friary, and there was also a church that belonged to the hospital of St. John. The Guest House on the corner of Palmer Lane provided lodgings for pilgrims to the priory, and there were numerous inns in the city to cater to the needs of travellers, merchants and local inhabitants.[35]

In 1465 the Coventry mint was established where nobles, half-nobles and groats were coined,[36] but it was disbanded a few years later, and the Golden Cross inn, built in 1583, now occupies the site. St. Mary's Hall, a guildhall built and extended 1340–1460,[37][dead link] served as the combined headquarters of the united guilds of the Holy Trinity, St. Mary, St. John the Baptist and St. Katherine. Following the suppression of guilds in 1547, for a time it served as the city's armoury and (until 1822) its treasury,[38] as well as the headquarters for administration for the city council until a new Council House was officially opened in 1920.[39]

Coventry's famous "Three Spires"; belonging to St. Michael's (300 ft / 91 m), Holy Trinity (about 230 ft / 70 m) and Christ Church (Greyfriars, just over 200 ft / 61 m),[40][41] dominated the skyline and would have been an impressive and easily recognised landmark for travellers and visitors to the city, as well as being visible from some distance.

When he visited Coventry c. 1540, the noted antiquarian John Leland was impressed by the "many fayre towers in the waulle" and "stately churches in the harte and midle of the towne" as well as its "many fayre stretes...well buyldyd with tymbar."[35]

Royalty and parliament

The growing importance of Coventry was reflected in the number of royal visits it received, and in recognition of its status Coventry was granted a city charter by King Edward III in 1345, endowing it with the rights of self-government such as the privilege of electing a mayor.[27] The motto "Camera Principis" (the Prince's Chamber) refers to his son Edward, the Black Prince.[42]

On one notable occasion, King Richard II assembled all the nobility of the realm on Gosford Green in 1398 to witness the combat between Henry Bolingbroke, the Duke of Hereford (who later became King Henry IV) and Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk.[43] Discord had grown between the two dukes and it had been decided that they should settle their differences in battle, but they were exiled instead to avoid bloodshed; Norfolk for life, Bolingbroke for 10 years.[44]

On several occasions Coventry was briefly the capital of England.[45][46] In 1404, Henry IV summoned a parliament in Coventry as he needed money to fight rebellion, which wealthy cities such as Coventry lent to him, while both Henry V and VI frequently sought loans from the city to meet the expense of the war with France.[43] During the Wars of the Roses, the Royal Court was moved to Coventry by Margaret of Anjou, the wife of Henry VI. On several occasions between 1456 and 1459 parliament was held in Coventry, which for a while served as the effective seat of government, but this would come to an end in 1461 when Edward IV was installed on the throne.

In 1451 King Henry VI granted Coventry a charter making Coventry a county in itself; a status it retained until 1842 when it reverted to being a part of Warwickshire.[47] During the county period it was known as the County of the City of Coventry. The original city hall was replaced by the current building in 1784 which is still known as "County Hall" as a relic of this period.[48]

Cheylesmore Manor House, currently the home of Coventry's Register office, lists Edward, the Black Prince and Henry VI among the royals who lived there. Parts of the building date to 1250, but those remnants of the main house that survived the Second World War were demolished in 1955. Edward's grandmother, Queen Isabella of France, had gained the manorial rights when the Crown acquired them from previous owners, and it is said that Edward was a frequenter of the area and used Cheylesmore Manor as his hunting lodge.

Edward's armour was black, hence the name "Black Prince", and his helmet was surmounted by a "cat-a-mountain". The seal of the city bears the motto "Camera Principis" or the Prince's Chamber which, it is said, it owes to the close tie with the Black Prince. The cat-a-mountain of the Black Prince also surmounts the coat of arms as a crest.

In October 1498, Arthur, Prince of Wales, made a Royal Entry to Coventry, and was welcomed by actors presenting King Arthur and the Nine Worthies, Queen Fortune, and Saint George defending a maiden from a dragon.[49] In the 16th century, due to the restrictive practices and monopolies of the trade guilds, the cloth trade declined and the city fell on hard times. Adding further concern and distress for the inhabitants of the city, this was accompanied by the dissolution of monasteries by King Henry VIII during the English Reformation which involved the destruction of Coventry's monastery and other religious houses in the city, followed shortly after by the suppression of religious guilds. However, most of Coventry's citizens appear to have favoured the new Protestant religion and English Bible – an attempt to restore the authority of the Roman Catholic religion during Queen Mary I's reign resulted in many suffering punishment rather than forsaking their belief. Between 1510 (under Henry VIII) and 1555, 12 Protestant martyrs were burned to death at the stake,[50] and a memorial to 11 of these Coventry Martyrs now stands not far from the site of execution in the Little Park. The burnings of three famous martyrs: Cornelius Bongey, Robert Glover and Laurence Saunders, all took place in 1555.[51] Many roads in Cheylesmore are named after these martyrs, see here for some local information.

Queen Elizabeth I stayed at the Whitefriars as a guest of John Hale in 1565, and then in 1569 Mary, Queen of Scots, was detained at St. Mary's Hall on Elizabeth's request.[51]

Civil War and aftermath

A sumptuous banquet was prepared in honour of King James I's visit to the city in 1617, but relations between the monarchy and Coventry deteriorated later when protests were made against his son's request for a considerable contribution of "ship-money" in 1635. Consequently, when the English Civil War broke out between King Charles I and Parliament, Coventry became a stronghold of the Parliamentarian forces.[52] On several occasions Coventry was attacked by Royalists, but each time they were unable to breach the city walls.

The King made an unsuccessful attempt to take the town in late August 1642, appearing at the city gates with 6,000 horse troops, but was strongly beaten back by the Coventry garrison and townspeople.[53] In 1645, the parliamentary garrison was under the command of Colonel Willoughbie, Colonel Boseville and Colonel Bridges with 156 officers and 1,120 soldiers. The garrison was supported by levies from surrounding villages; troops ranging across "several counties", imposing forced levies and taking horses and free quartering from villages in south-west Leicestershire.[54]

Coventry was used to confine Royalist prisoners. It is believed that the phrase "send to Coventry" (being treated coldly or ignored) may have grown out of the hostile attitude of residents of the city to either the troops billeted there, or towards the Scottish Royalist prisoners held in the Church of St. John the Baptist following the Battle of Preston. Another theory stems from Coventry being a place of execution during the 16th century, where supposed heretics would be sent to be burned.[55]

In 1662, after the restoration of the monarchy, in revenge for the support Coventry gave to the Parliamentarians during the Civil War, the city walls were demolished on the orders of King Charles II and now only a few short sections and two city gatehouses remain. When his brother, King James II visited the city in 1687, he received a magnificent reception in an outward show of loyalty to the Crown, but within two years most of the same people were celebrating the coming of William of Orange.[56]

Industrialisation

During the industrialisation phase of Coventry's evolution, connections were made with the expanding national transport networks. The Coventry Canal was opened in the late-18th century, and one of the first trunk railway lines, the London and Birmingham Railway, was built through Coventry and opened in 1838.

Textiles

It is known that a silk weaving company was founded in Coventry in 1627, and at around the start of the 18th century, a ribbon weaving works was established by a Mr. Bird (probably William Bird, silkman, who was mayor in 1705), assisted by a number of Huguenot refugees who brought with them silk and ribbon weaving skills. From small beginnings, the trade grew rapidly and by the end of the 18th century it had become the basis of the city's economy. Coventry began to recover, and again became a major centre of a number of clothing trades. At first single-shuttle hand-looms were used, later joined by the engine or many-shuttle looms, and by 1818 there were 5,483 single hand-looms and 3,008 engine looms in Coventry, with nearly 10,000 workers employed in the trade rising to a peak of 25,000 in about 1857.[57] A major employer was J&J Cash Ltd (Cash's), a silk weaving company founded in the 1840s by John and Joseph Cash in Foleshill.[58]

This first industrial boom came to a sudden end during the 1860s when foreign imports killed off the industry, and Coventry went into a slump. However, before long other industries began to develop and Coventry regained prosperity. Industries which developed included watch and clock making, manufacture of sewing machines, and from the 1880s onwards bicycle manufacture.

Clocks and watches

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Coventry became one of the three main UK centres of watch and clock manufacture and ranked alongside Prescot, near Liverpool and Clerkenwell in London.[59] However, the origins of clock and watch making in the city can probably be traced to the latter half of the 17th century. Samuel Watson, who was sheriff of Coventry in 1682, became famous for making an ingenious astronomical clock; John Carte, a watchmaker from Coventry had set up his own business in London by 1695, and the mayor of Coventry in 1727 was a watchmaker named George Porter. The firm of "Vale" was established in the late 1740s, and "Rotherhams" set up business in 1750. The next 60 years saw a rapid development in the trade with factories employing a number of specialised workers springing up alongside the workshops of individual master craftsmen. From 1825 to 1850, Coventry's business in watches almost doubled, and in 1861, some 2,037 people were employed in the trade.[60] As the industry declined from 1880 onwards, due mainly to competition from American and Swiss clock and watch manufacturers, the skilled pool of workers proved crucial to the setting up of sewing machine and bicycle manufacture, and eventually the motorcycle, automobile, machine tool and aircraft industries. However, Rotherhams were still making 100 watches a day in 1899 when many watchmakers had gone out of business.[61]

Cycles

The origins of cycle production in Coventry lie in the manufacture of sewing machines at the Coventry Machinists Company established in 1861 by James Starley. The company produced several successful models of sewing machine, and in 1868, Starley and his company were persuaded to manufacture the French-designed bone-shaker bicycles. Starley developed the design which led to the "Penny farthing" type and more practical tricycle designs, but ultimately it was his nephew John Kemp Starley who was responsible for inventing the first modern bicycle, the "Starley Safety Bicycle". Produced by Rover in 1885, it was the first bicycle to include modern features such as a chain-driven rear wheel with equal-sized wheels on the front and rear.[62]

By the 1890s the cycle trade was booming and Coventry had developed the largest bicycle industry in the world.[citation needed] The industry employed nearly 40,000 workers in the 248 cycle manufacturers that were based in Coventry. The peak year was 1896, but in 1906 for example, the Rudge-Whitworth Company alone made 75,000 of the 300,000 plus cycles manufactured in the city that year,[63] and the late 1920s saw Grindlay Peerless, a company founded by a future mayor of the city, Alfred Robert Grindlay, produce several record breaking motorcycles.

Effects on the city

This period of industrial growth was reflected in changes to the size and character of the city. The city walls had been largely pulled down in 1662,[64] but otherwise at the beginning of the 18th century its plan and appearance had changed little and was basically medieval with very old buildings, some much decayed.[65]

The city may be taken for the very picture of the city of London, on the south side of the Cheapside before the Great Fire; the timber-built houses, projecting forwards and towards one another, til in the narrow streets they were ready to touch one another at the top.

— Daniel Defoe, [65]

The advent of toll roads, regular stage coach services and increased road traffic meant that the old city gates that had been designed for the access of horse and cart now restricted the flow of traffic. Five of them were removed during the 18th century, and all but two of the remainder were demolished the following century. With industrial growth there was a corresponding rapid increase in population for which housing was needed. As all the existing streets were already built up, new houses were built on the remaining open spaces as well as on gardens and land at the rear of existing properties, and others were built outside the area of the old city. Over a period of 30 years, the number of houses in Coventry almost doubled from 2,930 in 1801, to 5,865 in 1831.[66]

In 1842 an Act of Parliament[which?] took away Coventry's county status and re-defined its boundaries as a city, but in recognition of its need to expand the revised boundaries enclosed 1,486 acres (6.01 km2), a considerably larger area than that of the old walled city. During the next 50 years, there were another two boundary extensions which absorbed further outlying districts, increasing the enclosed area to 4,417 acres (16.78 km2) in 1899.[67]

20th century

Industrial developments

The city continued to produce ribbons, woven labels and other small textile items, and 1904 heralded the opening of Courtaulds' first silk works at Foleshill in Coventry. The company was the first to produce nylon yarn in Britain in 1941.[68]

The first British motor car was made in Coventry in 1897 by The Daimler Motor Company Limited, and a growing number of other small motor manufacturers began to appear. The progress of this new industry was slow at first, but within 10 years the motor trade was employing some 10,000 people, and by the 1930s bicycle making had largely been replaced by motor manufacture which grew to employ 38,000 people by 1939.[69] Coventry had become a centre of the British motor industry; Jaguar, Rover and Rootes being just three of many famous British manufacturers to be based in the area.

The cycle and motor manufacturing industries brought into existence a wide variety of subsidiary trades. Most notably these were general engineering, metal casting, drop forging, chain-making and the manufacture of instruments and gauges, machine tools, and all types of electrical equipment. The manufacture of aircraft, aero engines and related equipment also took place in Coventry as early as 1916, and during World War II the aircraft industry dwarfed all other local industries. With the outbreak of war many of the motor firms switched to aircraft work, and the whole of Coventry's industrial skills and resources turned to war production of one sort or another.[68]

Great War (1914–1918)

Many Coventry factories switched production to military vehicles, armaments and ammunitions during the Great War. Approximately 35,000 men from Coventry and Warwickshire served during the First World War,[70] so most of the skilled factory workers were women drafted from all over the country.[71] Due to the importance of war production in Coventry it was a target for German zeppelin attacks and defensive anti-aircraft guns were established at Keresley and Wyken Grange to protect the city.[72]

In June 1921, the War Memorial Park was opened on the former Styvechale Common[73] to commemorate the 2587 soldiers[74] from the city who lost their lives in the war. The War Memorial was designed by Thomas Francis Tickner and is a Grade II* building.[75] It was unveiled by Earl Haig in 1927, with a room called the Chamber of Silence inside the monument holding the roll of honour.[76] Soldiers who have lost their lives in recent conflicts have been added to the roll of honour over the years.[77]

Changing character

Construction of a new Council House to take on the administration duties performed by St. Mary's Hall, and designed to be in keeping with its medieval surroundings, began in 1913 but was delayed during World War I. It was completed by 1917, but was not officially opened until 11 June 1920 by the Duke of York – later to become King George VI.[39]

As late as the 1920s, Coventry was being described as "The best preserved Medieval City in England". On visiting the city (before the devastation that resulted from the Blitz), the novelist J. B. Priestley wrote: "I knew it was an old place, but I was surprised to find how much of the past, in soaring stone and carved wood, still remained in the city."[78] However, the narrow medieval streets proved ill-suited to modern motor traffic, and during the 1930s many old streets were cleared to make way for wider roads, creating an odd mix of medieval and contemporary streets and buildings.

The city remained prosperous and largely immune to the economic slump of that decade. During the 1930s the population of Coventry grew by 90,000. There had been yet another boundary extension in 1928 which brought even more districts within the city limits, and extensive new housing estates were rapidly developed, particularly within those districts, though barely fast enough to keep pace with demand. By 1947 Coventry's boundaries enclosed 19,167 acres (77.57 km2).[79]

| Coventry Corporation Act 1927 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 29 July 1927 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

Catering to the needs of the city's growing population, the Coventry Corporation Act 1927 (17 & 18 Geo. 5. c. xc) reassigned Whitley Common, Hearsall Common, Barras Heath, and Radford Common as recreation grounds, and ended all the remaining traditional commoning rights on waste ground in Coventry, and the freemen of the city, who had been allowed to have up to three animals grazing on these areas since 1833, each received an annual sum of £100 as compensation.[80] The council had already purchased Styvechale Common from the Lords of Styvechale Manor following the First World War to create the War Memorial Park, and in 1927 a monument was built in the park to commemorate all Coventrians that died in that war, and since then later conflicts also.[81]

Starting in 1931, large sections of the city centre were demolished to make way for a new street plan, more suited to the motor car, with the timber-framed buildings to be replaced by modern structures. Initially, Fleet Street was replaced by Corporation Street, and in 1937 Little Butcher Row and Great Butcher Row gave way to Trinity Street. In 1938, Donald Gibson was appointed as City Architect, with a brief to plan major redevelopment of the city centre.[82]

IRA attack

Nine days before the outbreak of World War II, on 25 August 1939, Coventry was the scene of an early mainland bicycle bomb attack by the IRA. At 2:30 in the afternoon, a bomb exploded inside the carrier basket of a tradesman's bicycle that had been left outside a shop in Broadgate. The explosion killed five people, injured 100 more and caused extensive damage to shops in the area. The victims were John Corbett Arnott (15), Elsie Ansell (21), Rex Gentle (30), Gwilym Rowlands (50) and James Clay (82). Two IRA members and three others were put on trial for murder of one of the victims (Elsie Ansell). Three were acquitted and two convicted who were hanged in February 1940, although the identity of the man who rode the bicycle to Broadgate and planted the bomb was never discovered. The bomb plotters had been operating out of a house at 25 Clara Street.[83]

Bombing during the Blitz

Coventry's darkest hour came during World War II when Adolf Hitler singled out Coventry for heavy bombing raids.[citation needed] Large areas of the city were destroyed in a massive German bombing raid during the night of 14/15 November 1940. Firemen from throughout the Midlands came to fight the fires but found that each brigade had different connections for their hoses. Consequently, much fire-fighting equipment could not be used.[84]

The attack destroyed most of the city centre and the city's medieval cathedral; 568 people were killed, 4,330 homes were destroyed and thousands more damaged. Industry was also hard hit with 75% of factories being damaged, although war production was only briefly disrupted with much of it being continued in shadow factories around the city and further afield. Aside from London and Plymouth, Coventry suffered more damage than any other British city during the Luftwaffe attacks, with huge firestorms devastating most of the city centre.

The city was targeted due to its high concentration of armaments, munitions and engine plants which contributed greatly to the British war effort. Residential areas were not specifically targeted, although factories such as the Armstrong Siddeley aero engine plant (Parkside factory) were located in or near some of them. Following the raids the majority of Coventry's historic buildings could not be saved as they were in ruinous states or were deemed unsafe for any future use.

The devastation was so great that the word Koventrieren – to "Coventrate", or to annihilate or reduce to rubble[85] – entered the German and English languages. In response, the Royal Air Force intensified the carpet bombings against German towns.

On 8 April 1941 Coventry was hit by another massive air raid, which brought the total killed in the city by bombing to 1,236 with 1,746 injured.

A common myth surrounding the bombing (due in part to such books as Winterbotham's The Ultra Secret) is that Coventry was deliberately undefended to prevent the Germans realising that Enigma cipher machine traffic (information from which was termed Ultra) was being read by British cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park. This claim is untrue – Winston Churchill was aware that a major bombing raid was to take place, but no-one knew where the raid was meant to strike before it was too late to evacuate.[86][87]

Postwar

After the war, the city was extensively rebuilt. The new city centre built in the 1950s was designed by young town planner Donald Gibson and included one of Europe's first traffic-free shopping precincts.[citation needed]

The new Broadgate was opened by Princess Elizabeth in 1948,[88] and the rebuilt and reconsecreated Coventry Cathedral was opened in 1962 next to and incorporating the ruins of the old cathedral.[89][page needed] It was designed by Basil Spence and contains the tapestry, Christ in Glory in the Tetramorph by Graham Sutherland, the bronze statue St Michael's Victory over the Devil by Jacob Epstein that adorns the exterior wall and a striking memorial to Cuthbert Bardsley, bishop of Coventry from 1956 to 1976.

As a result of postwar redevelopment, Coventry now shares in the stereotype of 1960s architecture: concrete and brutalist. The development of Coventry's central business district was unnaturally restricted through the construction of a major orbital ringroad in the early-1970s, leading to a hodge-podge of "mixed use" city zones with no clearly defined functions, aside from the cathedral quarter and a 1950s shopping precinct. The construction of the Cathedral Lanes shopping complex in 1990 at Broadgate significantly altered the original layout. Nevertheless, several pockets of the city centre still have a number of medieval and neo-Gothic buildings (Ford's Hospital, The Golden Cross, St Mary's Guildhall, Spon Street, the Old Blue Coat School, the Council House, and the Holy Trinity Church etc.) having survived both the Blitz and the post-war planners.

The city was twinned with Dresden, which had suffered an even more devastating attack by the Anglo-American bombing late in the war, and groups from both cities became involved in demonstrations of post-war reconciliation.[90][91] The city played a major role in representing the entire nation when the reconstruction of the Dresden Frauenkirche was completed in 2003.

Throughout the 1950s and up until the mid-1970s, Coventry remained prosperous and was often monikered as "Motor City" or "Britain's Detroit" due to the large concentration of car production plants across the city, notably Jaguar, Standard-Triumph (part of British Leyland), Hillman-Chrysler (later Talbot and Peugeot) and Alvis. During this period, the city had one of the country's highest standards of living outside of south-eastern England. The population of the city peaked in the late-1960s at around 335,000.

The introduction of high-quality housing developments, particularly around the city's southern suburbs (such as Cannon Park, Styvechale Grange and south Finham) catered for a larger middle-class (and relatively well-paid working-class) population. Coupled with some of the UK's finest sporting and leisure facilities of the time, including an Olympic-standard swimming complex and a pedestrianised shopping precinct, Coventrians enjoyed a short-lived golden age.

However, the British industry was hit hard by industrial disputes, quality control issues and increasing foreign competition – as well as two recessions – between 1973 and 1982, and Coventry was among the cities affected. By 1982, unemployment in Coventry was approaching 20%, one of the highest rates of any British city at the time. A corresponding rapid increase in petty crime also began to give the city a poor reputation nationally. One of the biggest blows to hit the city during this era was the closure of the Triumph car factory at Canley in August 1980.[92]

The Rootes Group factory just outside the city at Ryton had been taken over by American carmaker Chrysler in 1964, which saw the company integrated with the French carmaker Simca. The company was sold to Peugeot in 1978 and the Talbot brand was introduced on the former Chrysler and Simca badged cars. Sales of the Ryton-built cars slumped during the early 1980s, but a few uncertain years the plant's future was secured when Peugeot decided to phase out the Talbot brand in the mid-1980s and built its own cars there.

A hit record widely believed to be about Coventry, "Ghost Town" by local band The Specials, summed up the situation in the city in the summer of 1981.[citation needed] The economic recession of 1990 to 1992 also hit the city hard, sparking another rise in unemployment and social discontent. Rioting took place in the Wood End, Bell Green and Willenhall areas of the city in May 1992 after gangs of local youths clashed with the police.[93] No further car production has taken place in Coventry since December 2006.[citation needed] However, motor production in the city still exists today in the form of the LTI (London Taxis International, formerly Carbodies) production plant in Holyhead Road, which employs 450 people and manufactures the popular "black cab", the current model being the TX4 which replaced the TXII in 2006. The world-famous FX4 black cabs were manufactured in Coventry from 1959 to 1994.

Coventry's famous medieval "Three Spires" belonging to St. Michael's, Holy Trinity and Christ Church (Greyfriars), have continued to dominate the skyline until the present day, but despite all three spires having survived, today only the church of Holy Trinity remains intact and in current use – the church of the Greyfriars was razed to the ground during the English Reformation, and only the walls and spire of St. Michael's survived the Coventry Blitz.

21st century

Some motor manufacturing continued into the early 21st century: The research and design headquarters of Jaguar Cars is in the city at their Whitley plant and although vehicle assembly ceased at the Browns Lane plant in 2004, Jaguar's head office returned to the city in 2011, and is also sited in Whitley. Jaguar is owned by the Indian company, Tata Motors. The closure of the Peugeot factory at Ryton-on-Dunsmore in 2006, ended volume car manufacture in Coventry.[94] By 2008, only one motor manufacturing plant was operational, that of LTI Ltd, producing the popular TX4 taxi cabs. On 17 March 2010 LTI announced they would no longer be producing bodies and chassis in Coventry, instead producing them in China and shipping them in for final assembly in Coventry.[95]

Since the 1980s, Coventry has recovered, with its economy diversifying into services, with engineering ceasing to be a mass employer, what remains of manufacturing in the city is driven by smaller more specialist firms. By the 2010s the biggest drivers of Coventry's economy had become its two large universities; the University of Warwick and Coventry University, which between them, had 60,000 students, and a combined annual budget of around £1 billion.[94]

In 2021 Coventry became the UK City of Culture.[96]

Education and public health

Schools

Until the beginning of the 19th century, education was neither compulsory, nor state-funded or controlled; however, in medieval Coventry there were educational opportunities for the poor, as well as the wealthy who could afford to pay the fees. The monks at St. Mary's priory ran a school for children of the poor from an early date; as well as a public grammar school in School House Lane from 1303 that had been endowed to them, for which fees would probably have been charged. It is believed that the Charterhouse, or Carthusian monastery, also kept a school for needy scholars, and that priests attached to various parish churches taught children in their spare time.[97]

As a result of the Reformation, many free educational opportunities for the poor disappeared, but following a brief period two new schools were established: the Free Grammar school (King Henry VIII School), and Bablake Hospital and School. The Free Grammar school was founded in 1545 by John Hales in the church formerly used by the Whitefriars, but following dispute of its ownership, the school moved to the former Hospital of St. John the Baptist ("the Old Grammar School") in 1558 where it remained until 1885.[98] The educational institution of Bablake School possibly originates from 1344 when the Bablake lands were granted by Queen Isabella. The school buildings were founded in 1560 when parts of the old guild buildings at Bablake were converted into a hospital and school, and then heavily endowed in 1563 by Thomas Wheatley.[99] The school taught sons of freemen of the city only.

As time passed, several smaller schools were founded in the city through charitable gifts and bequests, including the Blue Coat school for girls in 1714; and from 1790, Sunday schools were established to help provide further learning opportunities. Then, a "British" school for boys and a "National" school for boys and girls were built in 1811 and 1813 respectively,[100] funded partly by voluntary subscription and partly by fees. In 1833, the Government took an active interest and gave its first education grant, which encouraged several more small schools to follow in quick succession.[101]

An Act in 1870 led to the setting up of the Coventry School Board in 1871, which immediately built further schools in the city. In 1880, elementary education was made compulsory, and became free in 1891. The School Board was abolished under the Education Act 1902, and the local education authority for Coventry took its place. In the meantime, the Free Grammar school, renamed King Henry VIII School had moved in 1885 to its present address on Warwick Road,[101] and Bablake School moved to Coundon in 1890.[99] The building of a succession of further primary and secondary schools followed at various times during the 20th century.

Further education

As early as 1843, a School of Design had been opened in Coventry, followed in 1863 by a School of Art, and a Technical Institute in 1887 provided technical instruction related to local industries. Coventry Technical College, based at the Butts, was opened in 1935 and offered courses in engineering, construction, secretarial and cookery studies, reflecting the needs of the area at that time.[102] It merged with Tile Hill College of further education in 2002 to form the City College Coventry.[103]

Coventry College of Art amalgamated with Lanchester College of Technology and Rugby College of Engineering Technology in 1970 to become the Lanchester Polytechnic. In 1987 the name changed to Coventry Polytechnic and in 1992 it adopted the title Coventry University.[104]

The University of Warwick, located on the outskirts of Coventry, was established in 1965 and is consistently ranked in the Top Ten UK Universities in the national league tables.[105] Since its establishment, the university has incorporated the former Coventry College of Education in 1979, and has expanded its grounds to 721 acres (2.9 km2) with many modern buildings and academic facilities, lakes and woodlands.[106]

Coventry University, which dates back to the foundation of Coventry College of Design in 1843, has a 30-acre (12 ha) site in central Coventry.[citation needed]

Advent of healthcare and hospitals

The earliest example of organised healthcare in Coventry was in existence by at least 1793. The General or Charitable Dispensary was financed by charity alone, and was intended for those who had "such claims to respectability" that they should be saved from resorting to parish aid. This was joined in 1831 by the Provident Dispensary in Bayley Lane, one of the earliest self-supporting dispensaries. There were two classes of subscribers: honorary members, whose contributions took the form of charitable donations, and "free" members, who paid a weekly or yearly sum to secure medical benefits.[107]

Coventry's periodic rapid growth outstripped its sanitation systems: overcrowded, poor living conditions combined with ineffective sewerage, drainage and refuse disposal systems lead to frequent epidemics and a high death toll. When the Commissioners on the State of Large Towns investigated Coventry in 1843 they found that there was no Act or regulation in force regarding drainage or sewerage, and an inquiry under the Public Health Act 1848 lead to the city council being established as the local Board of Health in 1849 with associated powers,[107] and the first Medical Officer of Health was appointed in 1874.[108]

The increasing pressure on the General Dispensary during the 1830s drew attention to the need for a general hospital. The first, the Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital, was founded in 1838 in a converted private house.[107] The General Dispensary was merged with the hospital, and to cope with increasing demand, in 1863 a site in Stoney Stanton Road on which to build a larger hospital was acquired from Sir Thomas White's trustees and King Henry VIII Grammar School. The hospital was completed in 1866.[109]

Plans for a workhouse hospital were submitted in 1845, and in 1871 the Local Government Board approved a plan for an infectious diseases hospital (known first as the Poor Law Institution, and later until 1929,[110] the Coventry Poor Law Hospital) at the workhouse. By 1888 there was an infirmary with seven wards, but due to its inadequacy in several areas, the foundation stone of a new infirmary was laid in 1889. The workhouse infirmary combined the functions of a general, infectious diseases, and mental hospital.[107]

A serious scarlet fever outbreak in 1874 instigated the opening of a fever hospital in Coventry known as the City Isolation Hospital. The first stop-gap hospital was replaced by a larger one in 1885, where scarlet fever and diphtheria were the principal diseases dealt with after a separate smallpox hospital was erected at Pinley Hill Farm in 1897.[107][111]

Hospital expansion was steady for a while and generally related to demand, but the First World War provided further impetus and rapid industrial growth between the two World Wars was an important factor in further general growth.

Following the Local Government Act 1929, the public health committee of the corporation took control of the workhouse hospital, then renamed the Gulson Road Municipal Hospital. The hospital was open to all the sick inhabitants of Coventry, but priority was still given to the sick poor. The old workhouse was absorbed into the hospital in 1937.[107]

Paybody Hospital opened in 1929 as a convalescent home for crippled children when Thomas Paybody donated £2,000, together with a large house in Allesley, to the Coventry Crippled Children's Guild. About the same time, negotiations began for the sale of the old fever hospital in 1927–9, and the newly built Whitley Isolation Hospital opened in 1934.[107]

During the bombing of 1940–41, Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital was virtually destroyed, and although Gulson and Whitley hospitals also sustained damage, Gulson became the main casualty hospital while most other services were dispersed to other hospitals in the region.[107] In 1948, under the National Health Service Act 1946, Coventry Hospital Management Committee took over the control of 23 institutions and annexes, 10 of which lay within the boundaries of the city.[107][112] At the same time, the long-established Provident Dispensary was dissolved.

In 1951 Allesley House was closed, and Allesley Hall initially became an annexe of Paybody Hospital before closing in 1959. In 1962 the relatively few orthopaedic cases at Paybody Hospital were moved to Whitley Hospital to be replaced a year later by ophthalmic patients from the Keresley branch of the Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital.[107]

To meet the demands for a modern up-to-date general hospital, a new Walsgrave Hospital was opened in 1970,[113] replacing a hospital of the same name that had existed from 1926 to 1962.[114] Whitley Hospital closed in 1988,[115] followed by Gulson Road Hospital in 1998.[116]

Building work commenced on a new University Hospital project in 2002 which consolidated the Walsgrave and Coventry & Warwickshire hospitals into a single state-of-the-art development behind the existing Walsgrave Hospital site.[117] In 2006 the two hospitals moved into the University Hospital, and the existing Walsgrave Hospital was demolished in 2007.[118]

Historic population

- 16,000 (1801)

- 62,000 (1901)

- 220,000 (1945)

- 258,211 (1951)

- 335,238 (1971)

- 300,800 (2001)

Benefactors and founders

Leofric, Earl of Mercia and his wife Lady Godiva were responsible for the first major act of benevolence when they founded a monastery in the early settlement of Coventry, and some of the more notable benefactors and people that have since aided its development are listed as follows:[119]

- Thomas Bond

- draper, founded Bond's Hospital in 1506, and mayor of Coventry in 1497

- The Botoners

- merchant family, reputedly instrumental in the building of St. Michael's church-tower, spire, chancel and nave.[citation needed]

- Andrew Carnegie

- outside benefactor, gave £10,000 to the city for the building of libraries in Stoke, Earlsdon and Foleshill, all opened in 1913

- William Ford

- merchant, founder of Ford's hospital in 1529

- John Gulson

- founded Coventry's public library service and twice mayor 1867–69. Donated the site and most of the money for the building of the Gulson library adjacent to Holy Trinity church, opened in 1873. Also added a reference library in 1890

- John Hales

- writer and politician, founder of Coventry's Free Grammar school in 1545

- Sir Alfred Herbert

- pioneer of machine-tool production, converted a slum area into the public garden "Lady Herbert's Garden" in 1930, built and endowed "Lady Herbert's Homes" – two blocks of dwellings adjoining the garden, and funded restoration of the longest remaining portion of the city walls and Swanswell gate. Gave an initial gift of £100,000 and subsequent donations to the city for an art gallery and museum

- Lord Iliffe

- presented Allesley Hall and grounds to the city in 1937, and donated £35,000 towards the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral

- William Pisford

- co-founder of Ford's hospital

- Thomas Wheatley

- founder of Bablake school in 1560, and mayor of Coventry in 1556 [citation needed]

- Sir Thomas White

- merchant and businessman, associated with many acts of benevolence including a gift of £1,400 in 1542 for the city to buy lands to be held in trust for charitable purposes. The income from these lands was shared among deserving freemen of the city. (Also mayor of London in 1553, and founder of St. John's College, Oxford)

- Sir William Fitzthomas Wyley

- benefactor and twice mayor 1911–1912,[120][121] purchased and presented Cook Street gate to the city in 1913, bequeathed his residence, the Charterhouse, to the city in 1940. Also colonel and founder of Coventry and Warwickshire Society of Artists.[122][123]

See also

Notes

- ^ "UK City of Culture 2021: Coventry wins". BBC News. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Coventry, West Midlands". ARCHI. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ a b Coventry's beginnings in the Forest of Arden Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 2–3.

- ^ [1] BBC News. Retrieved 16 May 2024

- ^ [2] The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2024

- ^ Early forms of spelling: Couentre, Coventria, Couaentree, Cofentreo, Cofantreo, Cofentreium, Coventrev, Couintre. Later forms: Covintry, Covingtre, Coventrey, Coventre, Coventry. (Fox (1957) p. 2.)

- ^ Origin of Coventry's name on the historiccoventry website Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ a b c Fox (1957), p. 3.

- ^ "The history of Coventry Cathedral". Coventry Cathedral. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Leofric and Godiva". Historic Coventry. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Darlington et al. (1995), pp. 582–3.

- ^ Joan Cadogan Lancaster. Godiva of Coventry. With a chapter on the folk tradition of the story by H.R. Ellis Davidson. Coventry [Eng.] Coventry Corp., 1967. OCLC 1664951

- ^ K. L. French, 'The legend of Lady Godiva', Journal of Medieval History, 18 (1992), 3–19

- ^ "Cathedral status". Historic Coventry. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Expansion of Coventry's first cathedral". Historic Coventry. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 4–5.

- ^ "A Town of Two-Halves?". Historic Coventry. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Castle origins on thecoventrypages.net site Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 October 2008

- ^ a b c Coventry castle on the historic Coventry website Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 September 2008

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 27–28.

- ^ "The Doom painting – Medieval Coventry". Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Marie Stuart Society Mary, Queen of Scots: England

- ^ "Step inside Coventry's Guildhall". BBC Coventry and Warwickshire. BBC. 19 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ http://www.coventry.gov.uk: St. Mary's Guildhall Historical highlights: Did you know Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 6.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), p. 50.

- ^ True blue www.phrases.org.uk Retrieved 30 October 2008

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 61.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 29–30

- ^ a b City wall and gates on the historiccoventry website Retrieved 1 October 2008

- ^ The 12 city gates were: New Gate, Gosford Gate, Bastille Gate (later Mill Gate), Priory Gate (Swanswell Gate), Cook Street Gate, Bishop Gate, Well Street Gate, Hill Street Gate, Spon Gate, Greyfriars Gate, Cheylesmore Gate and Little Park Street Gate. (Fox (1957) p. 30.)

- ^ Fox (1957) p. 170.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 28–32.

- ^ Fox (1957) p. 173.

- ^ St, Mary's Guildhall on the historiccoventry website Retrieved 4 October 2008

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 96, 101, 175.

- ^ a b The Council House on the historiccoventry website Archived 4 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2008

- ^ Holy Trinity's spire was rebuilt sometime after 1666 to replace the original that was blown down and caused much damage to the church. (Fox (1957), p. 169.)

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 186.

- ^ "Coat of arms (crest) of Coventry". Heraldry of the World. 29 July 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Harriss (2005), p. 482.

- ^ Coventry Evening Telegraph, 19 October 1999

- ^ "Historic Coventry, England - Some History".

- ^ Home Office List of English Cities by Ancient Prescriptive Right, 1927, cited in Beckett, J. V. (2005). City status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7546-5067-6

- ^ Fox (1957) p. 172.

- ^ Sydney Anglo, Spectacle Pageantry, and Early Tudor Policy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), pp. 54–6.

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 181.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 13–15.

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 17.

- ^ The capture of Coventry on the coventryweb.co.uk site Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Coventry garrison on the coventryweb.co.uk site Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sent to Coventry" on the historiccoventry website Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 8 September 2009

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 18.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 68–70.

- ^ Cash's history Archived 2 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine J&J Cash Ltd website. Retrieved 6 October 2008

- ^ "Coventry Watch Museum Project". Coventry Watch Museum.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Fox (1957) p. 68.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 74.

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 38.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), p. 39.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 40–42.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 42–44.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 75–77.

- ^ Eccleston, Ben (11 July 2014). "World War One: When 35,000 local men went off to war". Coventry Live. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Waddington, Jenny (6 November 2018). "World War One: How Coventry fed the Allied war machine" Coventry Live. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Gibbons, Duncan (6 November 2018). "Watch out, Zeppelins! When Coventry looked with dread to the sky". Coventry Live. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Broster, Nicole. "History of War Memorial Park". Coventry City Council. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Coventry War Memorial Park Monument WW1 And WW2". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "War Memorial in Coventry War Memorial Park (1410358)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "War Memorial Park, Coventry - Coventry". Parks & Gardens. January 1925. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Pevsner, N. and Wedgewood, A., (1990) The Buildings of England: Warwickshire, p. 267.

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 47

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 45

- ^ "The City of Coventry – The common lands". A History of the County of Warwick. Vol. 8: The City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick. London: Victoria County History. 1969. pp. 199–207. Retrieved 5 October 2008 – via British History Online.

- ^ "History of the War Memorial Park". Coventry City Council. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ Gibbons, Duncan (13 November 2018). "Incredible old plans show what Coventry COULD have looked like". CoventryLive.

- ^ "Historic Coventry".

- ^ Regan (1996)

- ^ "This Day in History 1940". history.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ historiccoventry.co.uk

- ^ The Churchill Centre

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 151.

- ^ Walters 2019.

- ^ "Dresden, Germany". Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Dresden. "Coventry (United Kingdom)". www.dresden.de. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "The Last Car at Canley?". 6 April 2023.

- ^ ""All hell had broken loose" - 27th anniversary of Cov riots". 15 May 2016.

- ^ a b Walters 2019, pp. 170–186.

- ^ Lea, Robert (18 March 2010). "Manganese Bronze: Black cabs on the road to China". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "UK City of Culture 2021: Coventry wins". BBC News. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Bablake School history Retrieved 15 October 2008

- ^ Set up by two societies: the "British and Foreign Schools Society" and the "National Society", to further the cause of education.

- ^ a b Fox (1957), pp. 146–148.

- ^ The opening of Coventry Technical College City College Coventry. Retrieved 7 October 2008

- ^ Merger with Tile Hill College Archived 8 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine City College Coventry. Retrieved 7 October 2008

- ^ History of Coventry University Coventry University. Retrieved 7 October 2008

- ^ University ranking University of Warwick. Retrieved 7 October 2008

- ^ University history University of Warwick. Retrieved 7 October 2008

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 'The City of Coventry: Local government and public services: Public services', A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 8: The City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick (1969), pp. 275–298. British History Online. Retrieved 9 October 2008

- ^ Fox (1957), p. 113.

- ^ History of Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital Retrieved 8 October 2008

- ^ Gulson Hospital details The National Archives. Retrieved 8 October 2008

- ^ 'The City of Coventry: The outlying parts of Coventry: Pinley, Shortley, and Whitley', A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 8: The City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick (1969), pp. 83–90. Retrieved 9 October 2008

- ^ Institutions and annexes under the control of Coventry Hospital Management Committee Archived 5 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 10 October 2008. The institutions comprised Gulson Road and the Coventry and Warwickshire general hospitals (the latter with two annexes at Kenilworth and one at Keresley), Whitley infectious diseases hospital, the smallpox hospital at Pinley, a chronic hospital at Exhall with annexes at Walsgrave and Gosford Green, Paybody (now orthopaedic) hospital, Allesley Hall convalescent hospital and Allesley House maternity hospital (administered as annexes of Gulson Hospital), and Dunsmoor orthopaedic clinic.

- ^ Walsgrave Hospital data National archives. Retrieved 10 October 2008

- ^ Original Walsgrave Hospital data National archives. Retrieved 10 October 2008

- ^ Whitley Hospital data National archives. Retrieved 10 October 2008

- ^ Gulson Road Hospital data Hospital records database. Retrieved 10 October 2008

- ^ University Hospital details Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine University Hospital. Retrieved 8 October 2008

- ^ University Hospital timeline Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine University Hospital. Retrieved 8 October 2008

- ^ Fox (1957), pp. 162–168.

- ^ "The history of civic life: Previous Mayors and Lord Mayors". Coventry City Council. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Historic Coventry - List of Mayors & Lord Mayors". www.historiccoventry.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "History". Coventry & Warwickshire Society of Artists. 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Musing on Spines (1 May 2012). "Coventry and Warwickshire Society of Artists Celebrate Centenary Year". Creatabot. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

References

- Darlington, R.R., P. McGurk and J. Bray (1995). The Chronicle of John of Worcester. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fox, Levi (1957). Coventry's Heritage. Birmingham: Journal Printing Office.

- Harriss, Gerald (2005). Shaping the Nation: England, 1360–1461. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822816-3.

- McGrory, David (1993). Coventry: History and Guide. Dover, N.H.: A. Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-0194-2.

- Regan, Geoffrey (1996). The Guinness Book of Flying Blunders. Guinness Books. ISBN 0-85112-607-3.

- Slater, Terry (1981). A History of Warwickshire. London: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-416-0.

- Walters, Peter (2019). The Little History of Coventry. History Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7509-8908-4.

- The websites below were also used as references

Further reading

- Albert Smith and David Fry: (1991). The Coventry We Have Lost. Vol 1. Simanda Press, Berkswell. ISBN 0-9513867-1-9

- Albert Smith and David Fry: (1993). The Coventry We Have Lost. Vol 2. Simanda Press, Berkswell. ISBN 0-9513867-2-7