Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

| Cherokee Nation v. Georgia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Original jurisdiction Decided March 18, 1831 | |

| Full case name | The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia |

| Citations | 30 U.S. 1 (more) |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Original jurisdiction |

| Outcome | |

| The Supreme Court does not have original jurisdiction to hear a suit brought by the Cherokee Nation. The Court decided that Indian tribes, while retaining some sovereignty, were not foreign nations in the sense required to bring suit in federal court. Justice Marshall emphasized that the Constitution did not envision tribes as fully independent entities. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Marshall |

| Concurrence | Johnson |

| Concurrence | Baldwin |

| Dissent | Thompson, joined by Story |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. art. III | |

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation asked the Court to stop Georgia from enforcing state laws that took away their rights within the Cherokee territory. However, the Supreme Court declined to rule on the cases's merits, stating that it lacked the original jurisdiction, or authority, to decide in a matter between a U.S. state and the Cherokee Nation. Chief Justice John Marshall explained that the Cherokee Nation was not a "foreign nation" but a "domestic dependent nation," comparing their relationship with the United States to that of a "ward to its guardian."[1]

This case, part of the Marshall Trilogy, set a precedent for how Native American tribes are treated under federal law and unfolded against the backdrop of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, highlighting the growing tensions over tribal sovereignty.

Background

Historical Context

The Cherokee Nation had lived in what is now the southeastern United States for thousands of years. European contact began in 1542 when Hernando de Soto encountered Cherokee villages during his expedition.[2][3] By the late 17th century, the English began trading with the Cherokee, exchanging goods like firearms for alliances in conflicts such as the Tuscarora War.[4] Over time, the Cherokee integrated European-American culture, transitioning to a commercial hunting and farming lifestyle by the mid-18th century.[5] In 1775, one Cherokee village was described as having 100 houses, each with a garden, orchard, hothouse, and hog pens.[6]

Treaties, including the Treaty of Hopewell (1785) and the Treaty of Holston (1791), recognized Cherokee sovereignty and established agreements with the U.S. government.[7]

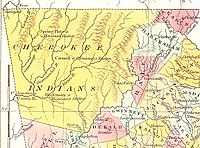

At the start of the 19th century, the Cherokee controlled about 53,000 square miles (140,000 km2) of land in Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. However, the U.S. government began pressuring the tribe to cede their land, particularly after an 1802 agreement promising Georgia that Cherokee lands would be opened to settlers. By 1817, the Treaty of the Cherokee Agency marked the beginning of the Indian Removal era, promising land west of the Mississippi River in exchange for Cherokee homelands. Despite adopting European-American farming practices and creating a written language and governing system, the Cherokee faced increasing encroachments on their land.

Cherokee Nation and the Push for Removal

By the early 19th century, white settlers, eager to expand into new lands, pressured the federal government to remove Native American tribes, including the Cherokee Nation. This pressure stemmed from promises made in the Compact of 1802, in which the U.S. government agreed to extinguish Cherokee land claims in Georgia.[8] While early policies under President Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe varied in their commitment to large-scale removal, the Cherokee faced growing external pressure despite their efforts to adopt European-American cultural practices, including farming and governance systems. President Thomas Jefferson also began to look at removing the tribe from their lands at this time.[9] Congress voted very small appropriations to support the removal, but policy changed under President James Monroe, who did not favor large-scale removal.[10]

At the same time, the Cherokee were adopting some elements of European-American culture.[fn 1] During this period until 1816, numerous other treaties were signed by the Cherokee. In each, they ceded land to the United States and allowed for roads to be constructed through Cherokee territory, but also kept the terms of the Holston treaty.[10]

In 1817, the Treaty of the Cherokee Agency[12] marked the beginning of a formal push for removal under the Indian Removal Act. The treaty promised an "acre for acre" land trade if the Cherokee would leave their homeland and move to areas west of the Mississippi River.[fn 2][14] However, by 1819, the Cherokee tribal government prohibited further land cessions, even imposing the death penalty for violations.[15] These measures underscored their resolve to defend their sovereignty and territory, but tensions with the state of Georgia escalated. By the 1820s, most of the Cherokee had adopted a farming lifestyle similar to that of neighboring European Americans.[16]

Georgia’s Role and the Rise of Andrew Jackson

By the 1820s, Georgia aggressively pursued the removal of the Cherokee, leveraging the 1802 Compact as justification.[17] In 1823, the state government and citizens of Georgia began to push for the removal of the Cherokee Nation. Congress responded by appropriating $30,000 to terminate Cherokee title to land in Georgia.[17]

In the fall of 1823, negotiators for the United States met with the Cherokee National Council at the tribe's capital city of New Echota, located in northwest Georgia. Joseph McMinn, noted for being in favor of removal, led the U.S. delegation.[18] When the negotiations to remove the tribe did not go well, the U.S. delegation supposedly resorted to trying to bribe the tribe's leaders.[fn 3]

In 1828, the state legislature of Georgia feared the United States would not enforce the removal of the Cherokee people from their historic lands in the state using federal policy. On December 20, 1828, Georgia passed laws stripping the Cherokee of legal protections within the state to ensure their forced removal.

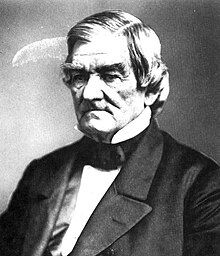

This state action coincided with the national election of President Andrew Jackson, a long-time proponent of Indian removal. Jackson's administration marked a turning point in federal policy, as he openly supported Georgia's actions and championed the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Cherokee Nation, led by Principal Chief John Ross, sought to resist Georgia's state laws. In January 1829, Chief Ross led a delegation to Washington in January 1829 to resolve disputes over the failure of the US government to pay annuities to the Cherokee and to seek federal enforcement of the boundary between the territory of the state of Georgia and the Cherokee Nation's historic tribal lands within that state. Rather than lead the delegation into futile negotiations with President Jackson, Ross wrote an immediate memorial to Congress, completely forgoing the customary correspondence and petitions to the President. Ross found support in Congress from individuals in the National Republican Party, such as senators Henry Clay, Theodore Frelinghuysen, and Daniel Webster, as well as representatives Ambrose Spencer and David (Davy) Crockett. Despite this support, in April 1829, John H. Eaton, the secretary of war (1829–1831), informed Ross that President Jackson would support the right of Georgia to extend its laws over the Cherokee Nation. In May 1830, Congress endorsed Jackson's policy of removal by passing the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to set aside lands west of the Mississippi River to exchange for the lands of Indian nations in the east. Along with the Indian Removal Act, the Treaty of New Echota was signed in 1835. This agreement stated that the Cherokee got compensation land in Mississippi and 5 million dollars in assistance in exchange for 7 million acres of land in Indian Territory.[20]

Congress’s passage of the Indian Removal Act further emboldened Georgia and the Jackson administration, setting the stage for legal and physical confrontations. Ross and the Cherokee turned to the courts as a last resort, laying the groundwork for significant legal battles, including Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and the later Worcester v. Georgia (1832).

Legacy of Andrew Jackson’s Policies

Andrew Jackson’s presidency left a lasting legacy on U.S.-Native relations, solidifying federal support for Indian removal. His policies culminated in the forced displacement of thousands of Native Americans, known as the Trail of Tears, and fundamentally reshaped the legal status of tribes as “domestic dependent nations.” Jackson’s actions and the Cherokee resistance became pivotal moments in the broader history of U.S. expansion, sovereignty disputes, and Native American rights.

The Case: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief John Ross and represented by William Wirt, a former United States attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, were selected to bring a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Backed by the supporters of Senators Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen, the Cherokee Nation sought an injunction against Georgia. They argued that Georgia's state legislation had created laws aimed to "annihilate the Cherokees as a political society." The Cherokee claimed that Georgia’s actions violated U.S.–Cherokee treaties, the U.S. Constitution, and federal laws regulating interactions with Native tribes.

Wirt contended that the Cherokee Nation qualified as a "foreign nation" under the Constitution and therefore had standing to sue. He asked the Court to nullify Georgia’s laws extending over Cherokee territory. Georgia countered by arguing that the Cherokee lacked standing as a foreign nation, citing their absence of a constitution and centralized government. Wirt argued that "the Cherokee Nation [was] a foreign nation in the sense of our constitution and law" and was not subject to Georgia's jurisdiction.

Wirt asked the Supreme Court to void all Georgia laws extended over Cherokee lands because they violated the U.S. Constitution, United States–Cherokee treaties, and United States intercourse laws.

The Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, agreed to hear the case but declined to rule on the merits of the case. The Court determined that the framers of the Constitution did not consider the Indian Tribes as foreign nations but more as "domestic dependent nation[s]" and consequently the Cherokee Nation lacked the standing to sue as a "foreign" nation.

Key Opinions[1]

Majority Opinion (Chief Justice John Marshall): Marshall concluded that Indian tribes, while retaining some sovereignty, were not foreign nations in the sense required to bring suit in federal court. He emphasized that the Constitution did not envision tribes as fully independent entities.[21]

Justice William Johnson (Concurring): Johnson described tribes as "nothing more than wandering hordes, held together only by ties of blood and habit, and having neither rules nor government beyond what is required in a savage state."[22] with no formal governance beyond blood ties and habits, underscoring their perceived lack of status as sovereign entities.

Dissenting Opinion (Justice Smith Thompson, joined by Justice Joseph Story): Thompson argued that the Cherokee Nation was a foreign state based on its ability to self-govern and enter treaties. He held that Georgia's laws violated federal treaties and acts of Congress, causing significant harm to the Cherokee. He supported the injunction against Georgia.

Aftermath and Legacy

Aftermath

One year later, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court reversed its stance, ruling that the Cherokee Nation was a sovereign entity. Chief Justice John Marshall emphasized that state laws had no authority within Cherokee territory, as the federal government had recognized Native nations as distinct political communities through treaties. This landmark decision established a critical precedent for federal protection of Native sovereignty.

Despite the ruling, President Andrew Jackson famously refused to enforce it, reportedly saying, “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.” Jackson directed the military to proceed with the removal of the Cherokee Nation, culminating in the Trail of Tears (1838–1839). In the spring of 1838, General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers were sent to remove Cherokees from present-day Oklahoma. Six forts were built to hold captured Cherokees until their removal in October 1838.[23] Over 4,000 Cherokee citizens died during this forced migration to Indian Territory, a tragic event that marked the violent erosion of Native rights and lands.[24]

Today, the Cherokee Nation is primarily located in northeastern Oklahoma, where it was forcibly relocated. It is one of the largest federally recognized tribes in the United States, with over 400,000 enrolled members. The Cherokee Nation maintains a sovereign government and oversees services such as healthcare, education, and economic development for its citizens, continuing to uphold its cultural and political legacy despite historical injustices.

Legacy

The Supreme Court’s dismissal of the Cherokee Nation’s claims in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia reflected the limitations of Native sovereignty under U.S. law to set the stage for continued federal and state encroachments on tribal autonomy. However, the subsequent Worcester v. Georgia decision has had enduring significance. It remains a cornerstone of legal arguments asserting tribal sovereignty and the federal government’s obligation to honor treaties.

Today, Native sovereignty is recognized as a fundamental principle of U.S. law, though it continues to face challenges. Tribes are considered "domestic dependent nations," retaining inherent rights to self-governance, control over their lands, and the ability to regulate their members and economic activities. However, conflicts persist over issues like jurisdiction, land rights, and resource management.

Modern Native advocacy often draws on Worcester v. Georgia to challenge federal and state policies that infringe on tribal sovereignty. Recent cases, such as McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), reaffirmed the principle that treaties with Native nations must be upheld, reinforcing tribal jurisdiction over their historic lands. These rulings highlight the lasting impact of the Cherokee Nation’s legal battles on contemporary interpretations of Native sovereignty.

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 30

- Worcester v. Georgia

- Tribal Sovereignty in the United States

Notes

- ^ By 1809 the tribe had a permanent police force, in 1817 the tribe had established a bicameral legislature, and by 1827 they had a written constitution and court.[11]

- ^ Most of the tribe was opposed to removal, and within a few years had successfully petitioned the federal government to prevent it.[13]

- ^ The commissioners, working through a Creek Indian chief, offered to give each Cherokee leader $2,000, equivalent to $38,328 in 2012. The chiefs rejected the bribe by denouncing it in front of the tribal council.[19]

References

- ^ a b Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831).

- ^ Robert J. Conley, The Cherokee Nation: A History 18–19 (2005)

- ^ Russell Thornton, C. Matthew Snipp, & Nancy Breen, The Cherokees: A Population History 10–11 (1992).

- ^ Conley, supra at 21–22; Thornton, supra at 19.

- ^ Conley, supra at 40–41.

- ^ Woodward, supra at 48.

- ^ Treaty with the Cherokee of 1791, July 2, 1791, 7 Stat. 39.

- ^ Cherokee Removal: Before and After xi (William L. Anderson, ed. 1992).

- ^ Eaton, supra at 21.

- ^ a b Eaton, supra at 20.

- ^ William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861 74–76 (1984); Eaton, supra at 17.

- ^ Treaty with the Cherokee of 1817, July 8, 1817, 7 Stat. 156

- ^ Eaton, supra at 29–31.

- ^ Starr, supra at 39.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 35–36.

- ^ Bryan H. Wildenthal, Native American Sovereignty on Trial: A Handbook With Cases, Laws, and Documents 36 (2003).

- ^ a b Eaton (1914), p. 39

- ^ Eaton, supra at 40–41.

- ^ Eaton, supra at 42–46.

- ^ "The Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears | NC DNCR". www.dncr.nc.gov. December 29, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ "Worcester v. Georgia." Oyez. Accessed 03 Aug. 2014. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1832/1832_2

- ^ Cherokee Nation v Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) at 190.

- ^ "The Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears | NC DNCR". www.dncr.nc.gov. December 29, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ "The Trail of Tears." pbs.org. Accessed 15 Oct. 2012. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h1567.html

Bibliography

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

- Canby, William C. "The Marshall Trilogy and Its Legacy." American Indian Law Review, vol. 34, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1-27.

- Conley, Robert J. (2005). The Cherokee Nation: A History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3236-3.

- Thornton, Russell; Snipp, C. Matthew; Breen, Nancy (1992) [1990]. The Cherokees: A Population History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9410-7.

- Woodward, Grace Steele (1963). The Cherokees. The Civilization of the American Indian. Vol. 65. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1815-6.

- Emmet, Starr (1921). History of the Cherokee Indians and their Legends and Folklore. Oklahoma City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Anderson, William L., ed. (1991). Cherokee Removal: Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1482-2.

- Eaton, Rachel Caroline (1914). John Ross and the Cherokee Indians. George Banta Publishing Company.

- McLoughlin, William G. (1984). Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-128-0.

- Wildenthal, Bryan H. (2003). Native American Sovereignty on Trial: A Handbook With Cases, Laws, and Documents. ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-624-5.

- Wilkinson, Charles F. (1987). American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04136-5.

Further reading

- Original Supreme Court Document: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

- More information on The Marshall Trilogy and the first few cases that greatly impacted Native communities: Canby, William C. "The Marshall Trilogy and Its Legacy." American Indian Law Review, vol. 34, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1-27.

- Provides the history of the Cherokee Nation and the reasons and outcomes of Supreme Court cases: Conley, R. J. (2005). The Cherokee Nation: A History. A Cherokee Publication.

- Anton-Herman Chroust, "Did President Andrew Jackson Actually Threaten the Supreme Court of the United States with Non-enforcement of Its Injunction Against the State of Georgia?," 4 Am. J. Legal Hist. 77 (1960).

- Kenneth W. Treacy, "Another View on Wirt in Cherokee Nation", 5 Am. J. Legal Hist. 385 (1961).

- Cherokee Nation Vs. The State Of Georgia (2009): 1. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 20 February 2012.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. Great American Court Cases. Ed. Mark Mikula and L. Mpho Mabunda. Vol. 4: Business and Government. Detroit: Gale, 1999. Gale Opposing Viewpoints In Context. Web. 20 February 2012.

External links

Works related to Cherokee Nation v. Georgia at Wikisource

Works related to Cherokee Nation v. Georgia at Wikisource- Text of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia case brief summary

- Cherokee Nation historical marker