Charles II, Duke of Parma

| Charles Louis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charles II in Spanish uniform, c. 1824 | |||||

| King of Etruria (as Louis II) | |||||

| Reign | 27 May 1803 – 10 December 1807 | ||||

| Predecessor | Louis I | ||||

| Regent | Maria Luisa of Spain | ||||

| Duke of Lucca (as Charles Louis) | |||||

| Reign | 13 March 1824 – 4 October 1847 | ||||

| Predecessor | Maria Luisa | ||||

| Duke of Parma and Piacenza (as Charles II) | |||||

| Reign | 17 December 1847 – 17 May 1849 | ||||

| Predecessor | Marie Louise | ||||

| Successor | Charles III | ||||

| Born | 22 December 1799 Royal Palace of Madrid, Madrid, Kingdom of Spain | ||||

| Died | 16 April 1883 (aged 83) Nice, French Republic | ||||

| Burial | Cappella della Macchia, Villa Borbone, near Viareggio | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon-Parma | ||||

| Father | Louis I, King of Etruria | ||||

| Mother | Maria Luisa, Duchess of Lucca | ||||

Charles Louis (Italian: Carlo Lodovico; 22 December 1799 – 16 April 1883) was King of Etruria (1803–1807; reigned as Louis II), Duke of Lucca (1824–1847; reigned as Charles Louis), and Duke of Parma (1847–1849; reigned as Charles II).

He was the only son of Louis, Prince of Piacenza, and his wife Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain. Born at the Royal Palace of Madrid at the court of his maternal grandfather King Charles IV of Spain, he spent his first years living at the Spanish court. In 1801, by the Treaty of Aranjuez, Charles became Crown Prince of Etruria, a newly created kingdom formed from territories of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. Charles moved to Italy with his parents and in 1803, not yet four years old, he succeeded his father as King of Etruria under the name Louis II.

His mother Infanta Maria Luisa assumed the regency while Charles Louis' minority lasted. In 1807 Napoleon Bonaparte dissolved the kingdom of Etruria and Charles Louis and his mother took refuge in Spain. In May 1808 they were forced to leave Spain by Napoleon who arrested Charles Louis' mother in a convent in Rome. Between 1811 and 1814 Charles Louis was placed under the care of his grandfather, the deposed King Charles IV of Spain.

After Napoleon's fall, in 1817, Infanta Maria Luisa became Duchess of Lucca in her own right and Charles Louis, age sixteen, became hereditary Prince of Lucca. In 1820 he married Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy. They were a mismatched couple and had only one surviving son.

At his mother's death in 1824, Charles Louis became the reigning Duke of Lucca.[1] He had little interest in ruling. He left the duchy in the hands of his ministers and spent most of his time traveling around Europe. A liberal movement led him to abdicate Lucca in favor of the Grand Duke of Tuscany in October 1847 in exchange for financial compensation, as he wanted to retire to private life. Two months later, in December 1847, at the death of the former Empress Marie Louise, he succeeded her as the reigning Duke of Parma according to what had been stipulated by the Congress of Vienna.

His reign in Parma as Duke Charles II was brief. He was ill-received by his new subjects and within a few months he was ousted by a revolution. He regained control of Parma under the protection of Austrian troops, but finally abdicated in favor of his son Charles III on 14 March 1849. His son was assassinated in 1854 and his grandson Robert I, the last reigning Duke of Parma, was deposed in 1860. In exile Charles Louis assumed the title of count of Villafranca. He spent the last years of his life mostly in France, dying at Nice on 16 April 1883.

Biography

Early life

Charles Louis was born at the Royal Palace of Madrid. His father, a member of the Bourbons of Parma, was Louis, Prince of Piacenza, son and heir of Ferdinand, Duke of Parma. His mother, Infanta Maria Louisa of Spain, was a daughter of King Charles IV of Spain. They had married in 1795 when the Hereditary Prince of Parma came to Madrid in search of a wife. The couple remained in Spain for the first years of their married life. It was for this reason that Charles Louis was born in Madrid at his maternal grandfather's court and he was included in Francisco de Goya's famous portrait of the family of Charles IV, in the arms of his mother.

Charles Louis's early life was over-shadowed by the actions of Napoleon Bonaparte who was interested in conquering the Italian states. French troops invaded the Duchy of Parma in 1796. In 1801, for the Treaty of Aranjuez, Charles Louis became Crown Prince of the newly created Kingdom of Etruria, formed from the former territories of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, as heir to his father, whom Napoleon had made King of Etruria in compensation for giving up his right to Parma.

On 21 April 1801 Charles Louis left Spain with his parents.[2] After a short visit to Napoleon in Paris, they moved to Florence taking residence in the Pitti palace, the former home of the Medici family. Only a few months after settling in Florence, the Etrurian royal family was called back to Spain.[2] It was during this trip that Charles's only sibling, Princess Maria Luisa Carlota of Parma, was born. Their visit was cut short by the death of Charles Louis' paternal grandfather, Ferdinand, Duke of Parma, who had clung to his throne until his death on 9 October 1802, when Parma passed to France under the terms of a treaty which he had signed.

In December 1802 the royal family of Etruria returned to Florence, but King Louis, who suffered from epilepsy and was frequently ill, died few months later on 27 May 1803.[2]

King of Etruria

After his father's death, Charles Louis, who was only three years old, succeeded him as King Charles Louis I of Etruria. He was under the regency of his mother Maria Luisa.[2] In 1807, Napoleon dissolved the kingdom and had Charles Louis and his mother brought to France. Charles Louis was promised the throne of a new Kingdom of Northern Lusitania (in the north of Portugal), but this plan never materialized, due to the break between Napoleon and the Spanish Bourbons in 1808. Charles Louis, his mother and sister looked for refuge in Spain, arriving at the court of Charles IV on 19 February 1808. Spain was in unrest, and less than three months after their arrival, all members of the Spanish Royal family were taken to France on Napoleon's orders, while Napoleon gave the Spanish crown to his brother Joseph Bonaparte.

Charles Louis left Spain with his mother and sister on 2 May 1808 for Bayonne and then Compiegne, the residence which had been assigned to them. Maria Luisa was promised the Ducal Palace of Colorno in Parma and a substantial allowance, but Napoleon did not keep his word and Charles Louis with his mother and sister were held captive in Nice.[2] When Charles Louis's mother tried to escape from Napoleon's grip, she was arrested and locked in a convent in Rome in August 1811. Charles Louis did not share his mother and sister's imprisonment. He was given in custody to his grandfather Charles IV, the deposed King of Spain. For the next four years, (1811–1815), Charles Louis lived under the care of his grandfather in the household of the exiled Spanish royal family in Rome.[3]

After Napoleon's downfall in 1815, the House of Bourbon was not restored to the Duchy of Parma, which was instead given to Napoleon's wife, the Empress Marie Louise. The Congress of Vienna compensated the Bourbons with the Duchy of Lucca, which was given to Charles Louis's mother, with Charles Louis as her heir, bearing the title Prince of Lucca. He was also promised the right of succession to Parma upon Empress Marie Louise's death.[3]

In December 1817, weeks before his eighteenth birthday, Charles Louis made his entry in Lucca with his mother. Due to the vicissitudes of the early years of his life he had not received a formal political education, but through self-teaching he acquired a vast knowledge.[citation needed] He was a Renaissance man with a wide range of interests, yet his fickle nature drawn him from his early youth to many different branches of knowledge, from medicine to music (he composed sacred music), to foreign languages.[citation needed] He was particularly oriented to humanities. Biblical and liturgical studies captured his interest. His ideology was influenced by the enlightening and romanticism of the period that followed the restoration of the European peace after the end of the Napoleonic wars.

As crown prince, he found himself subjected to continuous monitoring by his mother. Restless as he was, he clashed with his conservative mother who, in her later years, turned increasingly to religion. He also disliked her absolutist form of governing. However, from his mother, he inherited the love of the Spanish Bourbons for the pomp of a royal court. The relationship between mother and son turned sour with the years. He later complained that his mother had "ruined him physically, morally and financially".[3]

Marriage

In 1820 his mother arranged his marriage with Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy (1803–1879), one of the twin daughters of King Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia. The wedding took place in Lucca on 5 September 1820. Maria Theresa, who turned seventeen two weeks after the wedding, was tall and beautiful.[3] They were said to be the most handsome royal couple.[3] They had two children:

- Luisa Francesca (29 October 1821 – 8 September 1823)

- Charles III, Duke of Parma (14 January 1823 – 27 March 1854)

Charles Louis was witty, charming and of a gregarious nature. Maria Theresa was melancholic and, unlike her husband, she was a deeply devout Catholic.[3] They were a mismatched couple who lived most of their married life apart from each other. "Even if there was no love", Charles Louis later commented, "there was respect".[3]

Duke of Lucca

On 13 March 1824 Charles Louis' mother died and he succeeded her as the Duke of Lucca. Aged twenty-five, he inherited a small but well kept duchy.[3] However he showed a lack of interest in ruling. The turbulent episodes of his early life had affected him badly. In his own words "The stormy nature of my life, my inexperience, my good faith have unfortunate resulted in a complete lack of faith in myself and a diffidence, often involuntary but none the less inevitable towards, others."[3]

Charles Louis was initially uninterested in government, preferring to give free rein to his love for traveling. During the first few years of his reign he was largely absent from the duchy, leaving its government to his ministers led by Ascanio Mansi. From 1824 to 1827 Charles Louis traveled throughout Italy. He visited Rome and the courts of Naples and Modena often, he was less keen in staying with his in laws at the Piedmont Court which he disliked due to its austerity. From 1827 to 1833 he traveled thorough Germany where he owned two castles: Urschendorff (near Sankt Egyden am Steinfeld) and Weistropp (near Dresden). He enjoyed life at the Austrian court, where his sister in law was Empress. While in Vienna he rented the Kinsky Palace. He also spent time in Berlin, Frankfurt, Prague and in the capitals of other German states.

In the early 1830s Charles Louis began to take an increased interest in state affairs. His duchy was not affected by the revolutionary movements that ran across central Italy in 1831.[3] In foreign relations, he refused to recognize King Louis Philippe of France, who had come to power in the July Revolution of 1830. He was also allied with the Carlists in Spain supporting his uncle the Carlist claimant, Carlos V and with the legitimate (Miguelist) cause in Portugal (former King Miguel I of Portugal was his first cousin).

In 1833, after staying away for three years, Charles Louis returned to Lucca and granted a general amnesty. This was in stark contrast to the attitude of others Italian states that opted for repression and imprisonment. The same year Thomas Ward, a former English jockey, arrived in Lucca and in few years he became Charles Louis' adviser and minister. Charles Louis studied and collected biblical and liturgical texts and was interested in different religious rituals. He had built a Greek Orthodox chapel at his villa in Marlia, and he also flirted with Protestantism, which was viewed unfavourably by other Catholic courts.

Charles Louis made a number of administrative and financial reforms that were popular.[3] Between 1824 and 1829, some measures were taken relating to duties; to a certain freedom of trade; tax cuts, at the Land Registry. He gave especial encouragement to education and medicine, favoring the establishment of schools. These reforms were implemented thanks to the initiative of his Minister Mansi during the duke's absence. Charles disappointed his subjects who had hoped for a return to the constitution of 1805 and the hopes of Liberals in his duchy shifted to his only son and heir. He tried to copy in Lucca things he saw made abroad regardless if the conditions in the duchy were favorable. His love for traveling created many difficulties in governing and he often signed decrees according to his state of mind at the moment without any real knowledge of the issues. The actual power rested in his minister Mansi. It was said that while Charles Louis was the Duke, Mansi was king. Aware that Lucca was headed to be annexed by Tuscany, Mansi aligned his policies with those of Florence, which was resented by Charles Louis. However his weakness and his restless character did not allow Charles to escape the oppressive relations of protection and control exerted upon Lucca by the courts of Austria, Tuscany and Modena. He was viewed with suspicion by both Louis Philippe of France and Metternich.[4]

After 1833, Charles Louis, chronically short of money, stayed abroad less frequently. In 1836 he returned to Vienna and in 1838, after being in Milan for the coronation of Emperor Ferdinand, he went to France and then to England where he contracted debts. In 1837 he authorized the opening of a casino in Pieve Santo Stefano. The same year he promoted a reform of the State Council and the Council of Ministers. In 1840, while he was staying in Rome, his minister Ascanio Mansi died. Mansi's death heralded a new period during which Charles Louis took the initiative more, but his court drew adventures from different nationalities and Lucca became a haven for liberals fugitives from other states. Some of them were unscrupulous adventures of dubious reputation. He chose Antonio Mazzarosa, an eminent man, as presidency of the Council of State, but under Austrian pressure, he appointed Fabrizio Ostuni as Foreign Minister representing him at the Austrian court. Ostuni tenure lasted only three years (1840–1843) and coincided with a period of increasing financial distress. The economy of the duchy was in decline since 1830 and deteriorated further with the years. In 1841, the paintings of the Palatine Gallery had to be sold. The irregularities committed by Ostuni were discovered and denounced by Charles Louis' new right-hand man, Thomas Ward.[5]

Charles Louis rarely saw his wife, who after 1840 retired from public life and lived in religious seclusion in Pianore.[5] He visited her, but commented that her weak intellect and lack of sensitivity "would enable her to live a century".[5] Charles Louis admired female beauty, but was believed to be homosexual.[5] While in his Duchy, Charles was really little in his capital preferring to stay in the country in Marlia. In 1845 his son married princess Louise Marie Thérèse d'Artois, a daughter of the Duke of Berry and the only sister of the French legitimate pretender, the Count of Chambord.

Under pressure by Austria, Charles Louis agreed on some territorial adjustments that were detrimental to his future inheritance in Parma. By the treaty of Florence, on 28 November 1844, between Charles Louis and the dukes of Tuscany and Modena, he had to give up his claim to the Duchy of Guastalla and the lands east of the Enza. These territories would be given to Modena receiving in compensation only Lunigiana. The treaty of Florence remained a secret for nearly three years, but once it became known it contributed to Charles Louis growing unpopularity both in Lucca and in Parma. Need for money led the Duke, on the advice of Ward, who became Minister of Finance, to claim tax credits for titles dating back thirty years. All these resulted in general dissatisfaction. A liberal movement began to grow in Lucca where in 1847 there was a series of demonstrations, culminating in July in a full-scale riot. At first Charles Louis tried to assert his authority, but the continuous unrest forced him to take refuge in the Villa of San Martino in Vignale. On 1 September 1847, alarmed at the sight of a crowd that wanted to submit some reforms, he signed a series of concessions. Three days later, under pressure from many citizens, he returned to Lucca, where he was welcomed triumphantly. However he was unable to cope with the pressure and on 9 September he left for Modena. From there, he issued a decree that converted the Council of State in a Council of Regency. On 4 October he abdicated in favor of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who would in any case have taken the duchy when Charles Louis became Duke of Parma, meanwhile he was to receive a monthly economical compensation.[5] Thomas Ward arranged the premature handover; in a letter Charles told him "I can't describe to you how I feel and what a sacrifice I have made".[5] He left for Saxony while his family went to live in Turin under the protection of King Charles Albert of Sardinia.

Duke of Parma

Charles Louis wandered from Modena to his German estates.[5] Released from the burdens of government, he aspired to enjoy life as a free man dedicating his time to travel and study. However he soon received news that Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, was gravely ill. She died on 17 December 1847. He was faced with the dilemma of whether to accept or refuse the Duchy of Parma. Initially he was tempted to evade the new responsibilities that fell upon his shoulders, but ended up accepting it, so as not to compromise the rights of his son. On 31 December 1847, Charles Louis arrived in Parma and took possession of the throne of his ancestors with the name of Charles (Carlo) II. The Duchy of Lucca was incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, while Parma lost Guastalla but acquired Lunigiana.

Charles II was coldly received in Parma, a country and people he did not know well. He lacked the character and political acumen to be able to overcome a situation far more complicated than the one he had left behind in the much smaller Duchy of Lucca. Parma was dominated by Austria and he was not free to follow his own political ideas. He wrote to Ward. "It is better to die than to live like this. During the day, and when I am alone and can weep I weep. But that does not help."[5] He lacked the support of his cousins in Madrid and in Paris, even though he went in 1852 to Spain to recognize his cousin Isabella II as the legitimate Queen. In France Charles X had lost his throne in the 1830 revolution. He was a virtually prisoner in the palace and wanted to abdicate.[5]

In his first acts of government, he tried to organize the central administration. He also signed a military alliance with Austria. A few months after his arrival, the 1848 revolution broke out in Parma. He was forced to choose between suppressing the revolution or granting reforms. He decided for the latter and appointed a regency with the task of preparing a constitution. His intention was to save the throne for his son who asked for help from Charles Albert of Savoy. However Piacenza had already asked to join Piedmont and Charles Albert wanted annexation. On 9 April the regency transformed into a provisional government. Only four months after regaining the throne of his ancestors, Charles II was forced to flee from Italy, finding refuge in the castle of Weistropp in Saxony. On 19 April 1848, Charles abdicated in favor of his son, who had himself escaped.

During the First Italian War of Independence the Austrian army decisively defeated the troops of Charles Albert at Custoza, and then at Milan, forcing him to sign the armistice of Salasco on 9 August 1848. In April 1849, Austrian troops led by Marshall Radetzki occupied Parma and Piacenza. Charles II hastened to reassert its rights over the Duchy. He took control of the government under Austrian protection. Satisfied with securing the Duchy of Parma for his family, Charles presented his final resignation on 14 March 1849 at Weistropp in Saxony abdicating on his son.[5][6]

Last years

After his abdication Charles Louis assumed the title of Count of Villafranca.[7] Living as a private man, he dedicated his time to hobbies, alternating his stays between Paris, Nice and the castle of Weistropp in Saxony.

Always short of money, he sold his Austrian estate of Urschendorff to his friend Thomas Ward. In 1852 he went to Spain to recognize his cousin Isabella II as rightful queen.[citation needed] He began to return to Lucca where its citizen still had some sympathy for their former ruler despite his sale of the city.[citation needed] He was allowed to attend a family reunion held at Pianore in April 1853.

His only son Charles III, age 31, was assassinated on 27 March 1854.[7] In 1854 Charles Louis moved to Paris. In 1856 he visited his son's tomb in Viareggio and saw his wife. His grandson, Robert I, who was reigning in Parma under the regency of his mother, Louise Marie Thérèse, lost his throne in March 1860 during the Italian unification. Charles Louis, unlike other dethroned Italian monarchs, welcomed the unification of Italy as a positive development.[citation needed]

After 1860 Charles Louis was able to come to Italy more freely. He visited Lucca with increasing frequency staying in the Villas of Montignoso and San Martino in Vignale. His wife, Maria Theresa, who lived in complete retirement as a nun in villa San Martino in Lucca died on 16 July 1879.[7] Charles Louis was in Vienna at the time and only in October came to pay respect to her remains. His great granddaughter Archduchess Louise of Tuscany, later Crown Princess of Saxony, described him in her memoirs: "My maternal great grandfather, Duke Charles of Parma and Lucca was one of the most amusing and original men. He had estates in Saxony, to which he retired when he became weary of court life. He was always a protestant at Meissen, where his favorite castle was situated, and when he was remonstrated with on the subject by his spiritual advisers he replied. 'when I go to Constantinople I shall be a Mohammedan; In fact wherever I go I always adopt, for the time being, the religion of the country, as it keeps me so much more in tone with the local color scheme.'"[7]

Charles Louis survived his wife for less than three years. He died at Nice on 16 April 1883, age 83. He was buried at the large property at Viareggio belonging to the Parma family.[7]

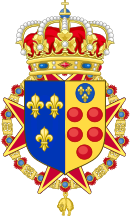

Heraldry

| Heraldry of Charles II of Parma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Etruria | Duchy of Lucca | Duchy of Parma | ||

|

|

|

|

|

| Coat of arms as Louis II of Etruria, Infante of Spain (1803-1807) |

Middle version (1803-1807) |

Lesser version (1803-1807) |

Coat of arms as Charles Louis Infante of Spain, Duke of Lucca and Knight of the Order of Santiago (1824-1847) |

Coat of arms as Charles II of Parma Infante of Spain (1761–1788) |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Charles II, Duke of Parma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 934–935.

- ^ a b c d e Sainz de Medrano, Changing Thrones: Duke Carlo of Parma, p. 98

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sainz de Medrano, Changing Thrones: Duke Carlo of Parma, p. 99

- ^ Trebiliani, M.L. Carlo II di Borbone . Dizionario biografico degli Parmigiani "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sainz de Medrano, Changing Thrones: Duke Carlo of Parma, p. 100

- ^ , Balansó, La Familia Rival, p. 101

- ^ a b c d e Sainz de Medrano, Changing Thrones: Duke Carlo of Parma, p. 101

Bibliography

- Balansó, Juan. La Familia Rival. Barcelona: Planeta, 1994.

- Lucarelli, Giuliano. Lo sconcertante duca di Lucca: Carlo Ludovico di Borbone Parma. Lucca: Fazzi, 1986.

- Mateos Sainz de Medrano. Ricardo. "Changing Thrones: Duke Carlo II of Parma". Royalty History Digest 3, no. 1 (July 1993).

- Trebiliani, M.L. Carlo II di Borbone. Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 20: 251–258. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. Text also available in the Dizionario biografico degli Parmigiani.