Bênção

| Chapa de frente | |

|---|---|

Chapa de frente or bênção kick | |

| Name | Chapa de frente |

| Meaning | front plate |

| AKA | Bênção |

| Type | kick |

| Parent style | capoeira Angola |

| Parent technique | engolo front push kick |

| Child technique(s) | low chapa de frente bênção pulada |

| Escapes | resistençia, ponte |

| Counters | rasteira |

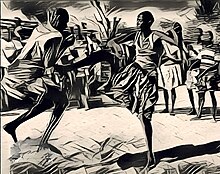

Chapa de frente (front plate) or bênção (blessing) is a front push kick with the sole of the foot.[1] In some variants, bênção can be done with the heel in the chest.[2]

Chapa de frente is one of the few fundamental kicks in capoeira.[3] It is also documented in African martial art engolo, the forerunner of capoeira.[4] This traditional capoeira kick is direct, firm and fast.[5]

Chapa de frente can be applied to numerous areas of the body, depending on the opponent's position.[6] It is commonly aimed at chest area.[6]

Names

Chapa de frente (front plate) is a descriptive name, because the kick belongs to the class of push kicks done with the sole of the foot, collectively known as chapa (plate[7]). This traditional name can be traced back to at least the mid-20th century.[6]

Bênção (blessing) is an ironic name, due to the bent starting position.[8] Slave owners in Brazil would meet their African slaves in the morning, especially on Sundays, and offer them blessings. The slaves had to bow and show gratitude, despite the mistreatment they endured. The benço kick reflects this contradiction, as the slave appears to receive a blessing but swings their foot forward to kick their opponent in the belly.[8]

Origin

Various push kicks are common in engolo, an Angolan martial art considered the ancestor of capoeira.[9] There are several types of push kicks in engolo including: front push kick (chapa de frente), back push kick (chapa de costas), side push kick (chapa lateral), revolving push kick (chapa giratoria) and push kick from inverted position.[4][10]

Technique

Bênção is executed by bringing the knee up before kicking. Then, there's a powerful forward push with the hips to leverage the extension of the kicking leg. The kick mainly hits with the sole, at the heel end of the flat foot.[1] The entire sole of the supporting foot should stay in contact with the floor.[1]

Typically, the capoeirista advances a step from the ginga towards the opponent before executing chapa de frente.[11] The kick proves particularly effective when it makes full contact with the opponent.[11]

The level of impact varies with its range from a soft tap to an inward jumping stomp. Chapa de frente is a very dangerous kick, not only because of the force with which it can be applied, but, above all, due to the delicate nature of the region of impact, where very sensitive organs are located.[6]

In the capoeira Angola, when a player completes a chapa de frente, they usually promptly descends to the ground, seeking refuge against potential takedowns or counterattacks aimed at their face.[12]

Variations

Low chapa de frente

There are a low variation of Chapa de frente, performed from the ground, usually from queda de quatro position. It involves pushing with the hips to increase both force and reach.

It is popular kick in capoeira Angola style.

Retreating version (escorão)

Escorão (scorer) is a cunning version of this kick, described by Burlamaqui. One draws back the foot and, simulating a retreat, quickly sends the foot into the enemy's abdomen.[13]

Jumping version (bênção pulada)

Sometimes the front push kick can be executed with excessive force, where the initial step evolves into a full-fledged leap, harnessing the entire weight of the player for the kick. In such cases, the person delivering the kick may lose control and be unable to retract the kick after it's launched. If the target is missed, there's a tendency to fall forward.[11]

Herein lies a lesson: In capoeira, when you attack in a very violent manner you are usually exposed to a counter-attack if the kick is not effective. Usually, kicks that "go for broke" are a two-edged sword, not only dangerous for the person being attacked but also for the attacker himself.[11]

This jumping push kick is referred to as the bênção pulada.[11]

Defenses

Defense against front push kick can be practiced in various ways. According to mestre Pastinha, one possible defense from a front plate is that a capoeirista blocks the attacker's leg with crossed forearms.[6] Another possibility is that the defender descends rapidly with crossed forearms, attempting to bring down the attacker by suspending their extended leg. Finally, the capuerista can use a counter attack against the front plate applied to their chest, by descending rapidly and attempting to bring down the attacker with a sweep (rasteira).[6]

The speed of movements and the flexibility of the body are essential for both attack and defense. A skilled capoeirista quickly discerns the intentions of the attacker, not wasting time in organizing their defense and counterattack. The mere position of the attacker indicates how they might attack.[6]

Literature

- Burlamaqui, Anibal (1928). Gymnástica nacional (capoeiragem), methodisada e regrada. Rio de Janeiro.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Da Costa, Lamartine Pereira (1961). Capoeiragem, a arte da defesa pessoal brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Oficial da Marinha.

- Pastinha, Mestre (1988). Capoeira Angola. Fundação Cultural do Estado da Bahia.

- Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2002). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-8086-6.

- Capoeira, Nestor (2007). The Little Capoeira Book. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 9781583941980.

- Desch-Obi, M. Thomas J. (2008). Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art Traditions in the Atlantic World. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-718-4.

- Talmon-Chvaicer, Maya (2008). The Hidden History of Capoeira: A Collision of Cultures in the Brazilian Battle Dance. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71723-7.

- Taylor, Gerard (2012). Capoeira 100: an Illustrated Guide to the Essential Movements and Techniques. Columbia: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 9781583941768.

References

- ^ a b c Taylor 2012, pp. 46.

- ^ Da Costa 1961, pp. 36.

- ^ Assunção 2002, pp. 157.

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 219–224.

- ^ Taylor 2012, pp. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pastinha 1988, pp. 64–68.

- ^ https://dicionario.priberam.org/chapa

- ^ a b Talmon-Chvaicer 2008, pp. 167.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 40.

- ^ Matthias Röhrig Assunção, Engolo and Capoeira. From Ethnic to Diasporic Combat Games in the Southern Atlantic

- ^ a b c d e Capoeira 2007, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Capoeira 2007, pp. 125.

- ^ Burlamaqui 1928, pp. 34.

See also