Changsha Kingdom

Changsha Kingdom 長沙國 | |

|---|---|

| 203/202 BC–AD 33 | |

Kingdoms of the Han dynasty in 195 BC, with Changsha shown in light green, at bottom centre[1] | |

| Status | Kingdom of the Han dynasty |

| Capital | Linxiang (present-day Changsha) |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | 203/202 BC |

• Extinction of the Wu family line | 157 BC |

• Reestablishment under the Liu family | 155 BC |

• Dissolution under Wang Mang | AD 9 |

• Restoration | AD 26 |

• Disestablished | AD 33 |

| Changsha Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 長沙國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长沙国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | State of Changsha | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The Changsha Kingdom was a kingdom within the Han Empire of China, located in present-day Hunan and some surrounding areas. The kingdom was founded when Emperor Gaozu granted the territory to his follower Wu Rui in 203 or 202 BC, around the same time as the establishment of the Han dynasty. Wu Rui and his descendants held the kingdom for five generations until Wu Zhu died without an heir in 157 BC. In 155 BC, the kingdom was reestablished for a member of the imperial family. However, the creation of this second kingdom coincided with the Rebellion of the Seven States and the subsequent reforms under Emperor Jing, and Changsha under the imperial family saw its autonomy greatly diminished. The kingdom was dissolved during Wang Mang's usurpation (AD 9 – 23), briefly restored after the founding of the Eastern Han, and finally abolished in AD 33 and converted to a commandery under the imperial government.

Changsha was one of the largest and longest-lasting kingdoms in Han China.[2] Despite being established on the empire's frontier, technology and art flourished in Changsha. Numerous archaeological sites of the kingdom have been discovered and excavated, most notably Mawangdui, the tomb of Changsha's chancellor Li Cang and his family, providing valuable insights into life in the kingdom and Han dynasty in general.

History

The first king of Changsha, Wu Rui, was a Baiyue leader who had been the magistrate of Poyang County under the Qin dynasty (221 – 207 BC). He enjoyed high prestige among the local people and was known as "Lord of the Po" (番君, Pójūn).[3][4]

In 209 BC, a peasant uprising triggered a wave of rebellions that resulted in the collapse of the Qin. After hearing news of the uprising, Wu Rui organized a mostly Baiyue army in support of the rebels. His forces soon grew to become a major faction in the civil war that ensued.[4] In 207 BC, Rui's army joined forces with the Han leader Liu Bang (the future Emperor Gaozu, at the time one of the rebel generals) and marched to the Guanzhong Plain, where they received the surrender of Ziying, the last ruler of Qin.[5] One year later, the Chu King Xiang Yu, then the most prominent leader in the rebellion, in an attempt to redivide the empire, recognized Rui as the "King of Hengshan" (衡山王, Héngshān Wáng). The Han eventually emerged victorious from post-Qin conflicts and established itself as the preeminent power in China. In 203/202 BC, Emperor Gaozu moved Wu Rui's fief[5] and established the Kingdom of Changsha.[6] The capital was Linxiang and located within the present-day city of Changsha.[7] The new kingdom helped the Han dynasty consolidate control over the Chu heartland and served as a buffer state against the independent realm of Nanyue founded by the Qin general Zhao Tuo in present-day Guangdong.[8][9] Rui died shortly after moving to his new territory, and the title passed to his son, Wu Chen (吳臣, Wú Chén).[10] Wu Chen reigned for eight years.[11]

The kings of Changsha were staunch supporters of the Han, and their loyalty and competence was praised by successive emperors.[12] In the first years after the founding of the Han Empire, the Emperor Gaozu embarked on a campaign to eliminate kings that were not members of the imperial family. The kings first grew to prominence as heads of independent factions in the chaos following Qin's fall, and the emperor viewed them as great threats to his authority. Changsha, located on the empire's southern fringe, was one of the weakest among the kingdoms; however, it was the only one to survive beyond 190s BC.[13][14] In 195 BC, Ying Bu, King of Huainan and son-in-law of Wu Rui, rebelled against the Han and was defeated. As Ying retreated south of the Yangtze River, the King of Changsha pretended to assist him in his escape to Nanyue but instead killed him in Cixiang (茲鄉, Cíxiāng) near Poyang.[15][16]

Wu Chen was succeeded by his son Wu Hui (吳回, Wú Huí). Hui reigned for seven years, and was succeeded by his son Wu You (吳右, Wú Yòu), whose name is also recorded as Wu Ruo (吳若, Wú Ruò).[11][17] At the time, the Han dynasty was under Emperor Hui and Empress Lü, who favored lenient laws and political views of the Huang–Lao school of philosophy. Changsha was able to develop under relative peace.[18] In 183 BC, however, Empress Lü banned the export of iron ware to Nanyue, which angered Zhao Tuo, who then proclaimed himself Emperor of Nanyue and then twice invaded Changsha, occupying a few counties.[19][20] Later, during Empress Lü's reign, the imperial court decided to launch a military campaign against Nanyue. However, in the hot and humid summer, a plague broke out in the Han army, hindering its advance. The campaign was eventually abandoned with the death of Empress Lü.[19] In 178 BC, the kingdom passed to Wu You's son Wu Zhu (吳著, Wú Zhù), for whom the names Wu Chai (吳差, Wú Chāi) and Wu Chan (吳產, Wú Chǎn) are alternatively used in some records.[21] Wu Zhu reigned for twenty-one years, dying in 157 BC without male issue.[2][22]

After the extinction of this house, Emperor Jing granted Changsha to his son Liu Fa (劉發, Liú Fā) in 155 BC.[22][14] Fa's mother, Tang (唐, Táng), was a servant of the Emperor's concubine Cheng (程, Chéng) and had given birth to Fa after the intoxicated emperor had mistaken her for his favorite concubine. Consequently, Fa had the lowest status among the Emperor's 14 sons and was enfeoffed in Changsha, far away from the capital Chang'an and the Central Plain.[23] Changsha Kingdom was held by the Liu family until early 1st century AD, when the Han dynasty was interrupted by usurper Wang Mang. Along with other kings of the Liu family in the empire, Liu Shun (劉舜, Liú Shùn), the last King of Changsha, was first demoted to the rank of duke and then stripped of his titles altogether.[24][25] After the restoration of Han dynasty, the Guangwu Emperor, himself a descendant of Liu Fa, gave Changsha to Liu Shun's son Liu Xing (劉興, Liú Xīng) in AD 26. In 33 the Emperor rescinded the decision and demoted Xing to the rank of a marquis, citing the distance of kinship between Xing and himself. Changsha was administered as an imperial commandery thereafter.[24]

Territory

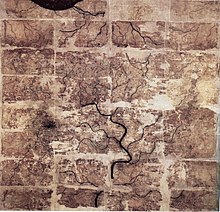

The exact extent of the first Changsha Kingdom is still unclear. The official Book of Han reports Changsha's border “reaching the north bank of Han River and stretching to Jiuyi Mountains”, although it is unlikely that Changsha actually reached so far. Similarly, it reports that, when Emperor Gaozu created the Kingdom of Changsha, he granted Wu Rui authority over the five commanderies of Changsha, Yuzhang (豫章, Yùzhāng), Xiang (象, Xiàng), Guilin (桂林, Guìlín) and Nanhai (南海, Nánhǎi). However, Yuzhang Commandery had already been conferred to Ying Bu, the King of Huainan, while Xiang, Guilin, and Nanhai Commanderies were all held by Zhao Tuo, the effectively independent King of Nanyue.[26] This state of the Changsha–Nanyue border was confirmed in a map unearthed from the Mawangdui tombs.[27][28] On the other hand, other preserved and unearthed texts have shown that there were two other commanderies actually controlled by the Changsha Kingdom: Wuling (武陵, Wǔlíng) and Guiyang (桂陽, Guìyáng). The first may have been granted by the imperial Han government; the historical geographer Zhou Zhenhe argues that the "Yuzhang" recorded in the Book of Han was simply a mistake for "Wuling", which would have been part of the original grant of the kingdom.[29] Guiyang was likely created by the kings of Changsha at some point for defense against invasions from Nanyue.[27][28]

The reconstruction offered by Zhou and Tan Qixiang is that Changsha's northern border ran along modern Tongcheng, Songzi, and Gong'an counties; the western border along modern Longshan, Zhenyuan, and Jingzhou counties; and the eastern border along modern Gao'an, Yichuan, Lianhua, and Chaling counties. Changsha's southern frontier with Nanyue was approximately the modern southern border of Hunan.[30]

When Emperor Jing granted Changsha to his son Liu Fa, the kingdom's territory was reduced to Changsha Commandery alone. Consequently, the kingdom's southwestern border was in the vicinity of modern Chaling, Wugang and Quanzhou counties.[30] From Emperor Wu's reign onward, 20 marquisates were created from Changsha. These marquisates were administered as parts of neighboring commanderies, further reducing the kingdom's territory.[31]

Demographics

Changsha was sparsely populated compared to other parts of the Han Empire.[32] The population primarily consisted of descendants of Chu colonizers, members of the Qin military garrison and their offspring, assimilated Nanman, and the native Baiyue tribes. Zhao Tuo, King of Nanyue, claimed that "half of Changsha are Man and Yi". Jia Yi, grand tutor of the king from 176 to 172 BC, wrote that there were only 25,000 households in the kingdom,[33] although it is likely that the figure was an underestimate.[34] (Jia, an advocate for further limits on the kingdoms' autonomy, saw Changsha's weakness as a reason of its loyalty.) However, the population increased rapidly, partly due to the favorable agricultural policies and partly because of immigration both from within the Han empire and from Nanyue.[35] In AD 2, when the Han dynasty conducted an empire-wide population census, the population of Changsha was recorded as 235,825 living in 43,470 households. The commanderies that constituted the larger Changsha of the early Han dynasty together had a population of 717,433 living in 126,858 households, a five-fold increase from Jia Yi's estimation during the early Han period.[36]

Government

In the early Han dynasty, the government structure of the kingdoms closely followed that of the Han central government, but differences remained.[37] Except for the chancellor and grand tutor (太傅, tàifù), who were selected by the imperial court, all officials were appointed by the king.[37] As in the imperial government, the chancellor (相國, xiàngguó, before 194 BC and 丞相, chéngxiàng, thereafter) was the highest civil office and the leader of the government.[38] However, the chancellor was not directly involved in the kingdom's everyday affairs, which were overseen by the court clerk (內史, nèishǐ). Compared to the central government, where the crown princes' tutors had little real authority, the grand tutor played a much more extensive role in a kingdom, as he supervised the king on behalf of the imperial government.[39] Meanwhile, the duties of the court clerk are reminiscent of the Warring States, where the post was second only to the chancellor in status, rather than the Han central government—the same post in the imperial government was merely in charge of finance and affairs in the capital region.[40][41] The responsibilities of the royal secretary (御史大夫, yùshǐ dàfū) were similar to the imperial equivalent, i.e. supervision over the bureaucrats, although his status was likely lower than the court clerk.[39] The imperial Nine Ministers also had their equivalents in the kingdom.[42] In addition, early Changsha had a unique office, the "pillar of state" (柱國, zhùguó). It was designation for an eminent official originating from the Chu state, but was not seen elsewhere in the Han dynasty;[41] the post may have merged into or been replaced by that of the chancellor.[43]

Under the Wu family, the Changsha Kingdom was administered at two levels, the commandery and the county. As described above, the state is believed to have consisted of the three commanderies of Changsha, Wuling, and Guiyang and to have claimed further commanderies under Nanyue's control. The three actual commanderies were divided into over 40 counties.[44][45] Under the cadet branch of the Liu family, the Changsha Kingdom eliminated the needless commandery level as its territory had been much reduced. In AD 2, the kingdom only administered thirteen counties.[44][45]

In regions inhabited by the Baiyue, larger but less populated circuits were used in place of counties. Two circuits—He (齕, Hé) and Ling (泠, Líng)—are noted on the map unearthed at Mawangdui. Counties were each headed by a magistrate and were subdivided into townships and villages (里, lǐ) in the same manner as in centrally administered territories of the Han dynasty.[25][46]

The reestablishment of the Changsha Kingdom under Liu Fa coincided with the abortive Rebellion of the Seven States and the subsequent drastic measures to limit the autonomy of kingdoms by Emperor Jing. In 145 BC, the vassal kingdoms were stripped of the right to appoint officials with salaries higher than 400 dan, which covered everyone from ministers in the royal court to county magistrates.[47] Furthermore, changes were made to the government hierarchy of kingdoms. A number of offices were abolished, including the royal secretary, minister of justice (廷尉, tíngwèi), minister of the royal clan (宗正, zōngzhèng), steward (少府, shǎofǔ), and court scholar (博士, bóshì).[48] Of particular importance was the abolition of the steward, as this move deprived the kings of their fiscal control over the fief.[47] Many remaining offices were demoted in rank, and lesser officials were reduced in number.[48] The titles of the chancellor and tutor were shortened to simply xiàng (相) and fù (傅) to distinguish them from their imperial equivalents.[47] Later, in 8 BC, the court clerk was abolished and the chancellor took over his duties. By then, the kingdom's government structure had become almost indistinguishable from that of a commandery in all but name.[47][48]

Kings

| Posthumous name | Personal name | Reigned from | Reigned to | Relationship with predecessor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | In Chinese | Pinyin | Name | In Chinese | Pinyin | |||

| Wu family | ||||||||

| King Wen of Changsha | 長沙文王 | Chángshā Wén Wáng | Wu Rui | 吳芮 | Wú Ruì | 203 BC | 202 BC | |

| King Cheng of Changsha | 長沙成王 | Chángshā Chéng Wáng | Wu Chen | 吳臣 | Wú Chén | 202 BC | 194 BC | Son |

| King Ai of Changsha | 長沙哀王 | Chángshā Āi Wáng | Wu Hui | 吳回 | Wú Huí | 194 BC | 187 BC | Son |

| King Gong of Changsha | 長沙共王 | Chángshā Gòng Wáng | Wu You | 吳右 | Wú Yòu | 187 BC | 179 BC | Son |

| King Jing of Changsha | 長沙靖王 | Chángshā Jìng Wáng | Wu Zhu | 吳著 | Wú Zhù | 179 BC | 157 BC | Son |

| Liu family | ||||||||

| King Ding of Changsha | 長沙定王 | Chángshā Dìng Wáng | Liu Fa | 劉發 | Liú Fā | 155 BC | 128 BC | |

| King Dai of Changsha | 長沙戴王 | Chángshā Dài Wáng | Liu Yong | 劉庸 | Liú Yōng | 128 BC | 101 BC | Son |

| King Qing of Changsha | 長沙頃王 | Chángshā Qīng Wáng | Liu Fuqu | 劉附朐 | Liú Fùqú | 101 BC | 83 BC | Son |

| King La of Changsha | 長沙剌王 | Chángshā Là Wáng | Liu Jiande | 劉建德 | Liú Jiàndé | 83 BC | 50 BC | Son |

| King Yang of Changsha | 長沙炀王 | Chángshā Yáng Wáng | Liu Dan | 劉旦 | Liú Dàn | 50 BC | 48 BC | Son |

| King Xiao of Changsha | 長沙孝王 | Chángshā Xiào Wáng | Liu Zong | 劉宗 | Liú Zōng | 45 BC | 43 BC | Brother |

| King Miu of Changsha | 長沙繆王 | Chángshā Miù Wáng | Liu Luren | 劉魯人 | Liú Lǔrén | 42 BC | AD 6 | Son |

| – | Liu Shun | 劉舜 | Liú Shùn | AD 6 | AD 9 | Son | ||

| – | Liu Xing | 劉興 | Liú Xīng | AD 26 | AD 33 | Son | ||

Economy

Agriculture in Changsha included a wide range of crops and animal species. Rice, the staple food in Changsha, was cultivated with a diverse range of varieties, while wheat, barley, common and foxtail millet, beans and hemp were also grown, as evidenced by seeds unearthed from tombs.[49] Fish farming and animal husbandry provided non-staple food for the population;[50] livestock such as horses, cattle and sheep were also exported to Nanyue.[51] Mawangdui tombs, the early 2nd century BC burial complex of chancellor Li Cang and his family, are a particularly rich source of knowledge on the kingdom. They have remnants of domesticated animals including pigs, cattle, sheep, dogs and chickens, as well as game animals and fowl.[52] Bamboo tablets recorded an assortment of dishes, with descriptions of multiple preparation techniques. Various types of alcoholic beverages, made from wheat, millet, and rice, were also discovered, indicating the development of local alcohol industry.[53]

Artifacts from Changsha noble tombs reveal advanced levels of artisanship. A plain-colored gauze gown discovered in the Mawangdui tomb, for example, measures 128 centimetres (50 in) long by 190 centimetres (75 in) wide but weights only 49 grams (1.7 oz) in total.[54] The intact embroidered silk from Mawangdui shows intricate patterns of swirling clouds, with more than 20 dyes used in the making of the diverse colors.[55] Glossily decorated lacquerware was manufactured a wide range of purposes, including dishes, furniture, and storage boxes.[56][57] Iron was widely applied for agricultural and military use, and ironwares found in Changsha tombs include spades, pickaxes, daggers, spears, swords, axes, and coins.[58] There were also records of tin mining in Changsha.[51]

Culture

Changsha nobility dressed similarly to contemporary nobles in the Han Empire. The forms of ancient Chinese clothing usually found in the tombs of Changsha aristocrats were silk gauze undergarments (襌衣, dānyī) and long robes with elaborately woven patterns.[59] Men typically wore hats, while a number of hairstyles can be seen in contemporary paintings and sculptures of women.[60]

The earliest known paintings on fabric in China were unearthed from the Mawangdui tombs.[61] Among them, a two-meter-long fēiyī (非衣, possibly meaning "flying garment")[62] in the tomb of Lady Dai is one of the finest examples of art in early China.[61] In the painting, Lady Dai was depicted in the center, accompanied by servants and surrounded by deities, mythological beasts, and symbols.[62][61] Several types of musical instruments were discovered in the Changsha tombs. They include the earliest known example of a guqin, a form of stringed instrument.[63] Archaeologists also found the first surviving examples of two previously lost ancient Chinese musical instruments, a woodwind known as a yú (竽) and a five-string instrument known as a zhù (筑).[64] Musical and dancing troupes consisting of dozens of performers were recorded in unearthed manuscripts.[65]

As seen in excavated manuscripts and artifacts, the Changsha elite practiced complicated incantations and ritual acts for their interaction with the spirit world. The calendrical system was incorporated into the religion, and Taiyi, the polar deity, was the central celestial deity.[66] An animistic pantheon was worshipped. In an iconographic image of Taiyi from Mawangdui, it was depicted with the Thunder Lord, the Rain Master (雨師, Yǔshī), and the Azure and Yellow Dragons, with explanatory texts on military fortunes associated with these deities.[67] A wide range of natural phenomena were connected with spirit powers, and instructions and devices on dealing with them have been found. These were among the religious elements that would later give rise to the Taoist religion.[66]

Science and technology

Some of the earliest texts on traditional Chinese medicine were discovered in the Mawangdui and Zhangjiashan tombs, most of which were previously unknown.[68] The largest of these finds is the Recipes for Fifty-two Illnesses (五十二病方, Wǔshí'èr Bìngfāng), which includes detailed treatments for specific illnesses. Two "cauterisation canons", the Cauterisation Canon of the Eleven Foot and Arm Channels (足臂十一脈灸經, Zúbì Shíyī Mài Jiǔjīng) and the Cauterisation Canon of the Eleven Yin and Yang Channels (陰陽十一脈灸經, Yīnyáng Shíyī Mài Jiǔjīng), provide important evidence about the concept of meridian channels in its infancy.[69] In addition, there are also texts on the philosophy and techniques of "nurturing life" (養生, yǎngshēng), covering practices from therapeutic gymnastics and dietetics to sexual cultivation.[69]

Two new texts on astronomy and astrology, the Prognostications on the Five Planets (五星占, Wǔ Xīng Zhàn) and the Diverse Prognostications on Heavenly Patterns and Formations of Materia Vitalis (天文氣象雜占, Tiānwén Qìxiàng Zá Zhàn), were found in the Mawangdui tombs.[70] The former provided accurate observation data on the positions of planets over a 70-year period from 246 BC to 177 BC, and also elaborated on some astrological beliefs such as an astral-terrestrial correspondence, a mapping of astronomical features to those on the land.[71][72] The latter, likely a work by a Chu author of the Warring States period, included a collection of illustrations of astronomical and atmospheric features such as clouds, mirages, rainbows, stars and comets.[73][74]

References

Citations

- ^ Zhou 1987, pp. 11–15.

- ^ a b He 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 13.

- ^ a b He 2013, p. 6.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Li 2014, p. 330.

- ^ He 2013, pp. 260–266.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ He 2013, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Li 2014, pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 28.

- ^ a b Loewe 1986, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Fu 1984, p. 106.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Fu 1984, p. 107.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 31.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Loewe 1986, p. 136.

- ^ Fu 1984, p. 113.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, p. 40.

- ^ a b Yi 1995, pp. 65–68.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 42.

- ^ a b Luo 1998, p. 41.

- ^ a b He 2013, p. 231.

- ^ Zhou 1987, p. 119.

- ^ a b He 2013, pp. 221–240.

- ^ Zhou 1987, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 50.

- ^ Fu 1984, p. 110.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 52.

- ^ a b He 2013, p. 250.

- ^ Wu 1990, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Wu 1990, p. 112.

- ^ Wu 1990, p. 111.

- ^ a b Wu 1990, p. 122.

- ^ Bielenstein 1980, p. 105.

- ^ He 2013, p. 254.

- ^ a b Fu 1984, p. 111.

- ^ a b He 2013, p. 175.

- ^ Loewe 1986, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d Bielenstein 1980, p. 106.

- ^ a b c He 2013, p. 253.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 193–199.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 199–202.

- ^ a b Fu 1984, p. 112.

- ^ Höllmann 2013, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Höllmann 2013, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 119.

- ^ Liu-Perkins 2014, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Liu-Perkins 2014, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 188–191.

- ^ a b c Li 2013, p. 319.

- ^ a b Liu-Perkins 2014, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Luo 1998, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b Harper 1999, p. 869.

- ^ Harper 1999, pp. 870–871.

- ^ Lo 2011, p. 19.

- ^ a b Lo 2011, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Pankenier 2013, p. 445.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Pankenier 2013, p. 285.

- ^ Luo 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Pankenier 2013, p. 497.

Bibliography

- Bielenstein, Hans (1980). The Bureaucracy of Han Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-75972-7.

- Fu Juyou (1984). "Changsha Guo Shulüe" [Overview of the Changsha Kingdom]. Qiusuo (in Chinese) (3): 106–113. doi:10.16059/j.cnki.cn43-1008/c.1984.03.023.

- Harper, Donald (1999). "Warring States Natural Philosophy and Occult Thought". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 813–884. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- He Xuhong (2013). Handai Changsha Guo Kaogu Faxian yu Yanjiu [Archaeological Discoveries and Research on the Han Dynasty Changsha Kingdom] (in Chinese). Changsha: Yuelu Shushe. ISBN 978-7-5538-0161-2.

- Höllmann, Thomas, O. (2013). The Land of the Five Flavors: A Cultural History of Chinese Cuisine. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-16186-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Li Feng (2013). Early China: A Social And Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71981-0.

- Li Shisheng (2014). "Handai Changsha Guo Shiliao Tanxi San Ze" [Three Analyses of Historical Materials Related to the Changsha Kingdom of the Han Dynasty]. Journal of Hunan Provincial Museum (in Chinese) (11): 330–334. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Liu-Perkins, Christine (2014). At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui. Watertown: Charlesbridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60734-615-9.

- Lo, Vivienne (2011). "Mai and Qi in the Western Han". In Hsu, Elizabeth (ed.). Innovation in Chinese Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–92. ISBN 978-0-521-18259-1.

- Loewe, Michael (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty". In Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K. (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume I: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–222. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Luo Qingkang (1998). Changsha Guo Yanjiu [Research on the Changsha Kingdom] (in Chinese). Changsha: Hunan People's Press. ISBN 978-7-5438-1947-4.

- Pankenier, David W. (2013). Astrology and Cosmology in Early China: Conforming Earth to Heaven. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00672-0.

- Wu Rongzeng (1990). "Xihan Wangguo Guanzhi Kaoshi" [Study on the Bureaucracy of Western Han Dynasty Kingdoms]. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) (in Chinese) (3): 109–122. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Yi Yuqiang (1995). "Xihan Changsha Guo de Zhiguan Jianzhi" [Establishment of the Bureaucracy in Western Han Dynasty Changsha Kingdom]. Journal of Hunan Educational Institute (in Chinese). 13 (3): 65–68. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Zhou Zhenhe (1987). Xihan Zhengqu Dili [Administrative Geography of the Western Han Dynasty] (in Chinese). Beijing: People's Press. ISBN 978-7-100-12898-8.

Further reading

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1193-7.