Cave

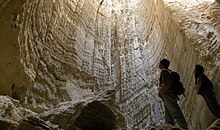

A cave or cavern is a natural void under the Earth's surface.[1] Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. Exogene caves are smaller openings that extend a relatively short distance underground (such as rock shelters). Caves which extend further underground than the opening is wide are called endogene caves.[2][3]

Speleology is the science of exploration and study of all aspects of caves and the cave environment. Visiting or exploring caves for recreation may be called caving, potholing, or spelunking.

Formation types

The formation and development of caves is known as speleogenesis; it can occur over the course of millions of years.[4] Caves can range widely in size, and are formed by various geological processes. These may involve a combination of chemical processes, erosion by water, tectonic forces, microorganisms, pressure, and atmospheric influences. Isotopic dating techniques can be applied to cave sediments, to determine the timescale of the geological events which formed and shaped present-day caves.[4]

It is estimated that a cave cannot be more than 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) vertically beneath the surface due to the pressure of overlying rocks. This does not, however, impose a maximum depth for a cave which is measured from its highest entrance to its lowest point, as the amount of rock above the lowest point is dependent on the topography of the landscape above it. For karst caves the maximum depth is determined on the basis of the lower limit of karst forming processes, coinciding with the base of the soluble carbonate rocks.[5] Most caves are formed in limestone by dissolution.[6]

Caves can be classified in various other ways as well, including a contrast between active and relict: active caves have water flowing through them; relict caves do not, though water may be retained in them. Types of active caves include inflow caves ("into which a stream sinks"), outflow caves ("from which a stream emerges"), and through caves ("traversed by a stream").[7]

Solutional

Solutional caves or karst caves are the most frequently occurring caves. Such caves form in rock that is soluble; most occur in limestone, but they can also form in other rocks including chalk, dolomite, marble, salt, and gypsum. Except for salt caves, solutional caves result when rock is dissolved by natural acid in groundwater that seeps through bedding planes, faults, joints, and comparable features. Over time cracks enlarge to become caves and cave systems.

The largest and most abundant solutional caves are located in limestone. Limestone dissolves under the action of rainwater and groundwater charged with H2CO3 (carbonic acid) and naturally occurring organic acids. The dissolution process produces a distinctive landform known as karst, characterized by sinkholes and underground drainage. Limestone caves are often adorned with calcium carbonate formations produced through slow precipitation. These include flowstones, stalactites, stalagmites, helictites, soda straws and columns. These secondary mineral deposits in caves are called speleothems.

The portions of a solutional cave that are below the water table or the local level of the groundwater will be flooded.[8]

Lechuguilla Cave in New Mexico and nearby Carlsbad Cavern are now believed to be examples of another type of solutional cave. They were formed by H2S (hydrogen sulfide) gas rising from below, where reservoirs of oil give off sulfurous fumes. This gas mixes with groundwater and forms H2SO4 (sulfuric acid). The acid then dissolves the limestone from below, rather than from above, by acidic water percolating from the surface.

Primary

Caves formed at the same time as the surrounding rock are called primary caves.

Lava tubes are formed through volcanic activity and are the most common primary caves. As lava flows downhill, its surface cools and solidifies. Hot liquid lava continues to flow under that crust, and if most of it flows out, a hollow tube remains. Such caves can be found in the Canary Islands, Jeju-do, the basaltic plains of Eastern Idaho, and in other places. Kazumura Cave near Hilo, Hawaii is a remarkably long and deep lava tube; it is 65.6 km long (40.8 mi).

Lava caves include but are not limited to lava tubes. Other caves formed through volcanic activity include rifts, lava molds, open vertical conduits, inflationary, blisters, among others.[9]

Sea or littoral

Sea caves are found along coasts around the world. A special case is littoral caves, which are formed by wave action in zones of weakness in sea cliffs. Often these weaknesses are faults, but they may also be dykes or bedding-plane contacts. Some wave-cut caves are now above sea level because of later uplift. Elsewhere, in places such as Thailand's Phang Nga Bay, solutional caves have been flooded by the sea and are now subject to littoral erosion. Sea caves are generally around 5 to 50 metres (16 to 164 ft) in length, but may exceed 300 metres (980 ft).

Corrasional or erosional

Corrasional or erosional caves are those that form entirely by erosion by flowing streams carrying rocks and other sediments. These can form in any type of rock, including hard rocks such as granite. Generally there must be some zone of weakness to guide the water, such as a fault or joint. A subtype of the erosional cave is the wind or aeolian cave, carved by wind-born sediments.[9] Many caves formed initially by solutional processes often undergo a subsequent phase of erosional or vadose enlargement where active streams or rivers pass through them.

Glacier

Glacier caves are formed by melting ice and flowing water within and under glaciers. The cavities are influenced by the very slow flow of the ice, which tends to collapse the caves again. Glacier caves are sometimes misidentified as "ice caves", though this latter term is properly reserved for bedrock caves that contain year-round ice formations.

Fracture

Fracture caves are formed when layers of more soluble minerals, such as gypsum, dissolve out from between layers of less soluble rock. These rocks fracture and collapse in blocks of stone.[10]

Talus

Talus caves are formed by the openings among large boulders that have fallen down into a random heap, often at the bases of cliffs.[11] These unstable deposits are called talus or scree, and may be subject to frequent rockfalls and landslides.

Anchialine

Anchialine caves are caves, usually coastal, containing a mixture of freshwater and saline water (usually sea water). They occur in many parts of the world, and often contain highly specialized and endemic fauna.[12]

Physical patterns

- Branchwork caves resemble surface dendritic stream patterns; they are made up of passages that join downstream as tributaries. Branchwork caves are the most common of cave patterns and are formed near sinkholes where groundwater recharge occurs. Each passage or branch is fed by a separate recharge source and converges into other higher order branches downstream.[13]

- Angular network caves form from intersecting fissures of carbonate rock that have had fractures widened by chemical erosion. These fractures form high, narrow, straight passages that persist in widespread closed loops.[13]

- Anastomotic caves largely resemble surface braided streams with their passages separating and then meeting further down drainage. They usually form along one bed or structure, and only rarely cross into upper or lower beds.[13]

- Spongework caves are formed when solution cavities are joined by mixing of chemically diverse water. The cavities form a pattern that is three-dimensional and random, resembling a sponge.[13]

- Ramiform caves form as irregular large rooms, galleries, and passages. These randomized three-dimensional rooms form from a rising water table that erodes the carbonate rock with hydrogen-sulfide enriched water.[13]

- Pit caves (vertical caves, potholes, or simply "pits") consist of a vertical shaft rather than a horizontal cave passage. They may or may not be associated with one of the above structural patterns.

Geographic distribution

Caves are found throughout the world, although the distribution of documented cave system is heavily skewed towards those countries where caving has been popular for many years (such as France, Italy, Australia, the UK, the United States, etc.). As a result, explored caves are found widely in Europe, Asia, North America and Oceania, but are sparse in South America, Africa, and Antarctica.

This is a rough generalization, as large expanses of North America and Asia contain no documented caves, whereas areas such as the Madagascar dry deciduous forests and parts of Brazil contain many documented caves. As the world's expanses of soluble bedrock are researched by cavers, the distribution of documented caves is likely to shift. For example, China, despite containing around half the world's exposed limestone—more than 1,000,000 square kilometres (390,000 sq mi)—has relatively few documented caves.

Records and superlatives

- The cave system with the greatest total length of surveyed passage is Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, US, at 675.9 km (420.0 mi).[14][15]

- The longest surveyed underwater cave, and second longest overall, is Sistema Ox Bel Ha in Yucatán, Mexico at 436 km (271 mi).[16]

- The deepest known cave—measured from its highest entrance to its lowest point—is Veryovkina Cave in Abkhazia, Georgia, with a depth of 2,204 m (7,231 ft).[17] This was the first cave to be explored to a depth of more than 2,000 m (6,600 ft). (The first cave to be descended below 1,000 m (3,300 ft) was Gouffre Berger in France.) The Sarma and Illyuzia-Mezhonnogo-Snezhnaya caves in Georgia, (1,830 m or 6,000 ft, and 1,753 m or 5,751 ft respectively) are the current second- and third-deepest caves.[17] The deepest outside Georgia is Lamprechtsofen Vogelschacht Weg Schacht in Austria, which is 1,623 m (5,325 ft) deep.[17]

- The deepest vertical shaft in a cave is 603 m (1,978 ft) in Vrtoglavica Cave in Slovenia. The second deepest is Ghar-e-Ghala at 562 m (1,844 ft) in the Parau massif near Kermanshah in Iran.[18]

- The deepest reached by a remotely operated underwater vehicle in an underwater cave is 450 metres (1,480 ft), in the Hranice Abyss in the Czech Republic.[19]

- The Miao Room is the world's largest known room by volume, with a measured volume of 10,780,000 m3 (381,000,000 cu ft).[20] The largest known room by surface is Sarawak Chamber, in the Gunung Mulu National Park (Miri, Sarawak, Borneo, Malaysia), a sloping, boulder strewn chamber with an area of 154,500 m2 (1,663,000 sq ft).[20] The largest room in a show cave is the Salle de la Verna in the French Pyrenees.

- The largest passage ever discovered is in the Son Doong Cave in Phong Nha-Kẻ Bàng National Park in Quảng Bình Province, Vietnam. It is 4.6 km (2.9 mi) in length, 80 m (260 ft) high and wide over most of its length, but over 140 m (460 ft) high and wide for part of its length.[21]

Five longest surveyed

- Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, US[14]

- Sistema Ox Bel Ha, Mexico[14]

- Sistema Sac Actun/Sistema Dos Ojos, Mexico[14]

- Jewel Cave, South Dakota, US[14]

- Shuanghedong Cave Network, China[14]

Ecology

Cave-inhabiting animals are often categorized as troglobites (cave-limited species), troglophiles (species that can live their entire lives in caves, but also occur in other environments), trogloxenes (species that use caves, but cannot complete their life cycle fully in caves) and accidentals (animals not in one of the previous categories). Some authors use separate terminology for aquatic forms (for example, stygobites, stygophiles, and stygoxenes).

Of these animals, the troglobites are perhaps the most unusual organisms. Troglobitic species often show a number of characteristics, termed troglomorphic, associated with their adaptation to subterranean life. These characteristics may include a loss of pigment (often resulting in a pale or white coloration), a loss of eyes (or at least of optical functionality), an elongation of appendages, and an enhancement of other senses (such as the ability to sense vibrations in water). Aquatic troglobites (or stygobites), such as the endangered Alabama cave shrimp, live in bodies of water found in caves and get nutrients from detritus washed into their caves and from the feces of bats and other cave inhabitants. Other aquatic troglobites include cave fish, and cave salamanders such as the olm and the Texas blind salamander.

Cave insects such as Oligaphorura (formerly Archaphorura) schoetti are troglophiles, reaching 1.7 millimetres (0.067 in) in length. They have extensive distribution and have been studied fairly widely. Most specimens are female, but a male specimen was collected from St Cuthberts Swallet in 1969.

Bats, such as the gray bat and Mexican free-tailed bat, are trogloxenes and are often found in caves; they forage outside of the caves. Some species of cave crickets are classified as trogloxenes, because they roost in caves by day and forage above ground at night.

Because of the fragility of cave ecosystems, and the fact that cave regions tend to be isolated from one another, caves harbor a number of endangered species, such as the Tooth cave spider, liphistius trapdoor spider, and the gray bat.

Caves are visited by many surface-living animals, including humans. These are usually relatively short-lived incursions, due to the lack of light and sustenance.

Cave entrances often have typical florae. For instance, in the eastern temperate United States, cave entrances are most frequently (and often densely) populated by the bulblet fern, Cystopteris bulbifera.

Archaeological and cultural importance

People have made use of caves throughout history. The earliest human fossils found in caves come from a series of caves near Krugersdorp and Mokopane in South Africa. The cave sites of Sterkfontein, Swartkrans, Kromdraai B, Drimolen, Malapa, Cooper's D, Gladysvale, Gondolin and Makapansgat have yielded a range of early human species dating back to between three and one million years ago, including Australopithecus africanus, Australopithecus sediba and Paranthropus robustus. However, it is not generally thought that these early humans were living in the caves, but that they were brought into the caves by carnivores that had killed them.

The first early hominid ever found in Africa, the Taung Child in 1924, was also thought for many years to come from a cave, where it had been deposited after being predated on by an eagle. However, this is now debated (Hopley et al., 2013; Am. J. Phys. Anthrop.). Caves do form in the dolomite of the Ghaap Plateau, including the Early, Middle and Later Stone Age site of Wonderwerk Cave; however, the caves that form along the escarpment's edge, like that hypothesised for the Taung Child, are formed within a secondary limestone deposit called tufa. There is numerous evidence for other early human species inhabiting caves from at least one million years ago in different parts of the world, including Homo erectus in China at Zhoukoudian, Homo rhodesiensis in South Africa at the Cave of Hearths (Makapansgat), Homo neanderthalensis and Homo heidelbergensis in Europe at Archaeological Site of Atapuerca, Homo floresiensis in Indonesia, and the Denisovans in southern Siberia.

In southern Africa, early modern humans regularly used sea caves as shelter starting about 180,000 years ago when they learned to exploit the sea for the first time.[26] The oldest known site is PP13B at Pinnacle Point. This may have allowed rapid expansion of humans out of Africa and colonization of areas of the world such as Australia by 60–50,000 years ago. Throughout southern Africa, Australia, and Europe, early modern humans used caves and rock shelters as sites for rock art, such as those at Giant's Castle. Caves such as the yaodong in China were used for shelter; other caves were used for burials (such as rock-cut tombs), or as religious sites (such as Buddhist caves). Among the known sacred caves are China's Cave of a Thousand Buddhas[27] and the sacred caves of Crete.

Paleolithic cave paintings have been found throughout the world dating from 64,800 years old for non-figurative art[28] and 43,900 years old for figurative art.[29]

Caves and acoustics

The importance of sound in caves predates a modern understanding of acoustics. Archaeologists have uncovered relationships between paintings of dots and lines, in specific areas of resonance, within the caves of Spain and France, as well as instruments depicting paleolithic motifs,[30] indicators of musical events and rituals. Clusters of paintings were often found in areas with notable acoustics, sometimes even replicating the sounds of the animals depicted on the walls. The human voice was also theorized to be used as an echolocation device to navigate darker areas of the caves where torches were less useful.[31] Dots of red ochre are often found in spaces with the highest resonance, where the production of paintings was too difficult.[32]

Caves continue to provide usage for modern-day explorers of acoustics. Today Cumberland Caverns provides one of the best examples for modern musical usages of caves. Not only are the caves utilized for reverberation, but for the dampening qualities of their abnormal faces as well. The irregularities in the walls of the Cumberland Caverns diffuse sounds bouncing off the walls and give the space an almost recording studio-like quality.[33] During the 20th century musicians began to explore the possibility of using caves as locations as clubs and concert halls, including the likes of Dinah Shore, Roy Acuff, and Benny Goodman.[citation needed] Unlike today, these early performances were typically held in the mouths of the caves, as the lack of technology made depths of the interior inaccessible with musical equipment.[34] In Luray Caverns, Virginia, a functioning organ has been developed that generates sound by mallets striking stalactites, each with a different pitch.[35]

See also

- Cave gate – Cave entrance barricade

- Subterranean waterfall – Waterfall located underground

- Caving – Recreational pastime of exploring cave systems

- Caving organizations

- Cenote – Natural pit or sinkhole that exposes groundwater underneath

- List of caves

- Pit cave – Cave with significant vertical passages

- Speleology – Science of cave and karst systems

- Speleothem – Structure formed in a cave by the deposition of minerals from water

- Subterranean river – River that runs wholly or partly beneath the ground surface

- Underground lake – Lake under the Earth's surface

Notes

References

- ^ "cave". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/8886318356. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Moratto, Michael J. (2014). California Archaeology. Academic Press. p. 304. ISBN 9781483277356.

- ^ Lowe, J. John; Walker, Michael J. C. (2014). Reconstructing Quaternary Environments. Routledge. pp. 141–42. ISBN 9781317753711.

- ^ a b Laureano, Fernando V.; Karmann, Ivo; Granger, Darryl E.; Auler, Augusto S.; Almeida, Renato P.; Cruz, Francisco W.; Strícks, Nicolás M.; Novello, Valdir F. (15 November 2016). "Two million years of river and cave aggradation in NE Brazil: Implications for speleogenesis and landscape evolution". Geomorphology. 273: 63–77. Bibcode:2016Geomo.273...63L. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.08.009.

- ^ Комиссия спелеологии и карстоведения. Д. А. Тимофеев, В. Н. Дублянский, Т. З. Кикнадзе. Терминология карста. Базис карстования Archived 2013-02-15 at the Wayback Machine D.A. Timofeev, V.N. Dublyansky, T.Z. Kiknadze, 1991, Karst Terminology, The Commission for Speleology and Karst, Moscow Center of the Russian Geographical Society

- ^ "How Caves Form". Nova (American TV series). Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Silvestru, Emil (2008). The Cave Book. New Leaf. p. 38. ISBN 9780890514962.

- ^ John Burcham. "Learning about caves; how caves are formed". Journey into amazing caves. Project Underground. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ a b Culver, David C. (2004). Encyclopedia of Caves. Elsevier Academic Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0121986513.

- ^ Mörner, Nils-Axel; Sjöberg, Rabbe (September 2018). "Merging the concepts of pseudokarst and paleoseismicity in Sweden: A unified theory on the formation of fractures, fracture caves, and angular block heape". International Journal of Speleology. 47 (3): 393–405. doi:10.5038/1827-806X.47.3.2225. ISSN 0392-6672.

- ^ Kolawole, F.; Anifowose, A. Y. B. (1 January 2011). "Talus Caves: Geotourist Attractions Formed by Spheroidal and Exfoliation Weathering on Akure-Ado Inselbergs, Southwestern Nigeria". Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management. 4 (3): 1–6. doi:10.4314/ejesm.v4i3.1. ISSN 1998-0507.

- ^ "Peldanga Labyrinth (Liepniekvalka Caves), Latvia - redzet.eu". www.redzet.eu. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Easterbrook, Don, 1999, Surface Processes and Landforms [2nd edition], New Jersey, Prentice Hall, p. 207

- ^ a b c d e f "World's Longest Caves List from The National Speleological Society". 21 August 2022. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ National Park Service (8 September 2022). "Mammoth Cave Just Got A Little More "Mammoth" - Mammoth Cave National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "CINDAQ 2022 Annual report". CINDAQ. El Centro Investigador del Sistema Acuífero de Quintana Roo A.C.(CINDAQ). 26 January 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b c "World's Deepest Caves List from The National Speleological Society". Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Brocklebank, Tony. "Iranian cavers discover one of the world's deepest shafts". Darkness Below UK. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Hranice Abyss is believed to be 1200 m. deep (in Czech)". August 2022.

- ^ a b Vergano, Dan (28 September 2014). "China's "Supercave" Takes Title as World's Most Enormous Cavern". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Owen, James (4 July 2009). "World's Biggest Cave Found in Vietnam". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ World Heritage Sites: a Complete Guide to 1007 UNESCO World Heritage Sites (6th ed.). UNESCO Publishing. 2014. p. 607. ISBN 978-1-77085-640-0. OCLC 910986576.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Cueva de las Manos, Río Pinturas". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Renshaw, Amanda, ed. (2013). Art & Place: Site-Specific Art of the Americas. Phaidon Press. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-0-7148-6551-5. OCLC 865298990. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Podestá, María Mercedes; Raffino, Rodolfo A.; Paunero, Rafael Sebastián; Rolandi, Diana S. (2005). El arte rupestre de Argentina indígena: Patagonia (in Spanish). Grupo Abierto Communicaciones. ISBN 978-987-1121-16-8. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Marean, Curtis W.; Bar-Matthews, Miryam; Bernatchez, Jocelyn; Fisher, Erich; Goldberg, Paul; Herries, Andy I. R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Jerardino, Antonieta; Karkanas, Panagiotis; Minichillo, Tom; Nilssen, Peter J.; Thompson, Erin; Watts, Ian; Williams, Hope M. (2007). "Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene" (PDF). Nature. 449 (7164): 905–908. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..905M. doi:10.1038/nature06204. PMID 17943129. S2CID 4387442.

- ^ Olsen, Brad (2004). Sacred Places Around the World: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 9781888729160.

- ^ D. L. Hoffmann; C. D. Standish; M. García-Diez; P. B. Pettitt; J. A. Milton; J. Zilhão; J. J. Alcolea-González; P. Cantalejo-Duarte; H. Collado; R. de Balbín; M. Lorblanchet; J. Ramos-Muñoz; G.-Ch. Weniger; A. W. G. Pike (2018). "U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art". Science. 359 (6378): 912–915. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..912H. doi:10.1126/science.aap7778. hdl:10498/21578. PMID 29472483. "we present dating results for three sites in Spain that show that cave art emerged in Iberia substantially earlier than previously thought. Uranium-thorium (U-Th) dates on carbonate crusts overlying paintings provide minimum ages for a red linear motif in La Pasiega (Cantabria), a hand stencil in Maltravieso (Extremadura), and red-painted speleothems in Ardales (Andalucía). Collectively, these results show that cave art in Iberia is older than 64.8 thousand years (ka). This cave art is the earliest dated so far and predates, by at least 20 ka, the arrival of modern humans in Europe, which implies Neandertal authorship."

- ^ Aubert, M.; et al. (11 December 2019). "Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art". Nature. 576 (7787): 442–445. Bibcode:2019Natur.576..442A. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y. PMID 31827284. S2CID 209311825.

- ^ Fazenda, Bruno (11 September 2017). "Cave acoustics in prehistory: Exploring the association of Palaeolithic visual motifs and acoustic response". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 142 (1332): 1332–1349. Bibcode:2017ASAJ..142.1332F. doi:10.1121/1.4998721. PMID 28964077.

- ^ Whipps, Heather (3 July 2008). "Turns out, cavemen loved to sing". Archived from the original on 22 May 2015.

- ^ "Music Went With Cave Art In Prehistoric Caves". 5 July 2008.

- ^ Farmer, Blake (11 August 2015). "Cumberland Caverns: A Subterranean Concert Venue In Tennessee".

- ^ Parton, Chris (4 June 2018). "Why Brandi Carlile, Steve Earle and More Are Performing in a Tennessee Cave". RollingStone. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Real Live Cave Music: Marvel at the World's Largest Instrument". YouTube. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2020.