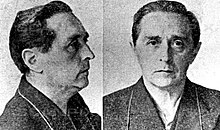

Carl Værnet

Carl Værnet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Carl Peter Jensen |

| Born | 28 April 1893 Jutland, Denmark |

| Died | 25 November 1965 (aged 72) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Buried | Cementerio Británico |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1944–1945 |

| Rank | SS-Sturmbannführer (major) |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Children | Kjeld Værnet |

Carl Peter Værnet (April 28, 1893 – November 25, 1965) was a Danish doctor at Buchenwald concentration camp and an SS-Sturmbannführer. Værnet attempted to cure homosexuality by implanting artificial hormone glands into male prisoners at Buchenwald. Although he was arrested after World War II, Værnet fled to Argentina where he practiced medicine until his death.[1]

Early life and education

Carl Værnet was born Carl Peter Jensen in Jutland, Denmark. In 1921, he changed his last name to Værnet (in Danish, to protect).[1] He was educated as a physician at the University of Copenhagen where he obtained his degree of medicine in 1923.[2]

Værnet worked as a general practitioner in Copenhagen, popular for his alternative treatments.[1]

Nazi Germany and Buchenwald

Værnet joined the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark in the late 1930s. After his membership in the Danish Nazi Party and collaboration with German occupants became known, his patients abandoned him and his professional and financial situation worsened.[1] In October 1943, three months after his clinic had been bombed by the resistance group Holger Danske, Værnet and his family moved to Berlin on invitation.[1]

In Berlin, Værnet was introduced to deputy Reich SS Physician Ernst-Robert Grawitz, who was personal assistant to Heinrich Himmler. Himmler, determined to eliminate homosexuality from Nazi Germany, was interested in Værnet's proposal to cure male homosexuality through an artificial hormonal gland implanted under the skin, which would release testosterone.[1][3]

Heinrich Himmler wrote "treat Værnet with the utmost generosity. I request a report of three to four pages each month because I am very interested in these things". Værnet was relocated to Prague to carry out his research at Buchenwald concentration camp under "German Medicines Ltd".[3]: 281 He was given an apartment originally belonging to Jews.[1]

Værnet traveled between Prague and Buchenwald, first arriving to the camp on the 26th of July 1944. He was supported in his work by the camp doctor Gerhard Schiedlausky.[4] Up to 17 men were involved in the experiment,[1] although Vaernet implanted capsules into 12 of the prisoners.[3]: 281 These included "real homosexuals" and some castrated heterosexual offenders.[1] According to Simon LeVay, at least 10 of these men were homosexual.[4]

Although Schiedlausky reported that a total of 13 men received implants, Grau notes that "Shielausky's figure of 13 operations is contentious. The first was performed by Værnet on 13.9.44 on five prisoners, the second on 8.12.44 on a further seven".[3]

According to notes written by the senior doctor at Buchenwald dated 3 January 1945, at least one man died during the experiment on 21 December 1944 ‘‘of heart failure associated with infectious enteritis and general bodily weakness". Eugen Kogon reported that a second man died as a result of the operations due to festering inflammation of cell tissue, presumably after 3 January 1945.[5] Little is known about fate of the other victims, as none are known to have applied for financial compensation after 1945.[6]

Værnet claimed that "successes" with the implants occurred,[5] presumably due to positive reports from prisoners hoping to receive a release from the camp,[4] or knowing it would increase their odds of survival.[5] The lack of scientific evaluation on the effectiveness of Værnet's experiment gave rise to suspicion from the SS camp officers.[1] Værnet's final report to Himmler on 10 February 1945 reported that his hormonal research remained unfinished,[7]: 184 and included excessive praise of Himmler, perhaps in an attempt to distract from his lack of results.[1]

The hypothesis that levels of circulating hormones determined (or cured) male homosexual orientation was later discredited by scientific research, and the organizational role of hormones prior to birth became a more influential hypothesis.[4]: 120

Post-war and escape to Argentina

After the war, Værnet returned to Copenhagen and was arrested. He was detained at Alsgade Skole prisoner-of-war camp, run by the British major Ronald F Hemingway, who said that Værnet “undoubtedly will be sentenced as a war criminal”.[8] However, he was released with the help of his son Kjeld Værnet who claimed he had a "life threatening" heart condition, and argued of the importance his artificial endocrine gland that promised "tremendous export revenues" for Denmark.[1] Hemingway authorised his transfer to a hospital, however records show that Værnet’s heart tests were normal and that he did not receive treatment.[8]

On his father's behalf, Kjeld Værnet unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate the sale of the artificial gland to a large British–American pharmaceutical company.[1] However, Kjeld Værnet was successful in arranging his father's escape to Argentina via Stockholm, Sweden.[1] A medical colleague of Værnet’s informed the Danish public prosecutor that his declining health required a vitamin E treatment that was available in Sweden. Værnet was given a permit to travel to Sweden and was able to support himself with a state stipend he received.[8]

Værnet fled to Buenos Aires, Argentina. He received Argentinian citizenship under the name "Carlos Peter Værnet" and worked as a general practitioner.[1] Kjeld Værnet twice unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate impunity to allow his father's return to Denmark.[1] However, the Danish government decided not to extradite him.[8]

Carl Værnet died in 1965 and was buried in Cementerio Británico, Buenos Aires. His son Kjeld Værnet (1920–1999) was a respected neurosurgeon at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.[1] According to Peter Tatchell, Værnet's files at the Danish National Archives remain classified and closed until 2025.[8]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kondziella D, Hansen K, Zeidman L (2013). "Scandinavian Neuroscience during the Nazi Era" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 40 (4): 493–502. doi:10.1017/S0317167100014578. PMID 23786731.

- ^ Davidsen-Nielsen, Hans (2002). Værnet: den danske SS-læge i Buchenwald (in Danish). J.P. Bøger. ISBN 978-87-90959-28-9.

- ^ a b c d Günter, Grau (1995). Hidden Holocaust? Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany, 1933-45. Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 281–292. ISBN 978-1-134-26105-5 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d LeVay, Simon (1996). Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research into Homosexuality. MIT Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-262-12199-6. OL 975823M – via Open Library.

- ^ a b c Röll, Wolfgang (1996). "Homosexual Inmates in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp". Journal of Homosexuality. 31 (4): 24–25. doi:10.1300/J082v31n04_01. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 8905527.

- ^ Günter 1995, p. 282.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2015). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-7990-6.

- ^ a b c d e Tatchell, Peter (2015-05-05). "The Nazi doctor who experimented on gay people – and Britain helped to escape justice". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-10-03.

Further reading

- THE HUNT FOR THE DANISH KZ – petertatchell.net

- The Nazi doctor who experimented on gay people – and Britain helped to escape justice Peter Tatchell (2015)

- Olivier Charneux, Les guérir, biography of Carl Vaernet in French, Robert Laffont, 2016

- The Buchenwald Report