Carl Sandburg

Carl Sandburg | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Sandburg in 1923 | |

| Born | Carl Sandberg[1] January 6, 1878 Galesburg, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | July 22, 1967 (aged 89) Flat Rock, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

| Education | Lombard College (non-graduate) |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Military Service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | U.S. Army |

| Years of service | 1898 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 6th Illinois Infantry |

| Battles / wars | Spanish–American War • Puerto Rico |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Edward Steichen (brother-in-law) George Crile Jr. (son-in-law) Mary Calderone (niece) |

| Signature | |

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg was widely regarded as "a major figure in contemporary literature", especially for volumes of his collected verse, including Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920).[2] He enjoyed "unrivaled appeal as a poet in his day, perhaps because the breadth of his experiences connected him with so many strands of American life".[3] When he died in 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson observed that "Carl Sandburg was more than the voice of America, more than the poet of its strength and genius. He was America."[4]

Life

Carl Sandburg was born in a three-room cottage at 313 East Third Street in Galesburg, Illinois, to Clara Mathilda (née Anderson) and August Sandberg,[1] both of Swedish ancestry.[5] He adopted the nickname "Charles" or "Charlie" in elementary school at about the same time he and his two oldest siblings changed the spelling of their last name to "Sandburg".[1][6][7]

At the age of thirteen, he left school and began driving a milk wagon. From the age of about fourteen until he was seventeen or eighteen, he worked as a porter at the Union Hotel barbershop in Galesburg.[8] After that, he was on the milk route again for 18 months. He then became a bricklayer and a farm laborer on the wheat plains of Kansas.[9] After an interval spent at Lombard College in Galesburg,[10] he became a hotel servant in Denver, then a coal-heaver in Omaha. He began his writing career as a journalist for the Chicago Daily News. Later, he wrote poetry, history, biographies, novels, children's literature, and film reviews. Sandburg also collected and edited books of ballads and folklore. He spent most of his life in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan before moving to North Carolina.

Sandburg volunteered to join the military during the Spanish–American War and was stationed in Puerto Rico with the 6th Illinois Infantry,[11] disembarking at Guánica, Puerto Rico, on July 25, 1898. Sandburg was never actually called to battle. He attended West Point for just two weeks before failing a mathematics and grammar exam. Sandburg returned to Galesburg and entered Lombard College but left without a degree in 1903. He then moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to work for a newspaper, and also joined the Wisconsin Social Democratic Party, the name by which the Socialist Party of America was known in the state. Sandburg served as a secretary to Emil Seidel, socialist mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. Carl Sandburg later remarked that Milwaukee was where he got his bearings and that the rest of his life had been "the unrolling of a scene that started up in Wisconsin".[12]

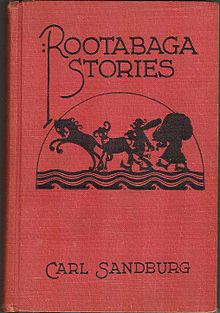

Sandburg met Lilian Steichen (1883–1977) at the Milwaukee Social Democratic Party office in 1907, and they married the next year in Milwaukee. Lilian's brother was the photographer Edward Steichen. Sandburg with his wife, whom he called Paula, raised three daughters. Their first daughter, Margaret, was born in 1911. The Sandburgs moved to Harbert, Michigan, and then to suburban Chicago, Illinois in 1912 after he was offered a job by a Chicago newspaper.[12] They lived in Evanston, Illinois, before settling at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst, Illinois, from 1919 to 1930. During the time, Sandburg wrote Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920).[2] In 1919 Sandburg won a Pulitzer Prize "made possible by a special grant from The Poetry Society" for his collection Cornhuskers.[13] Sandburg also wrote three children's books in Elmhurst: Rootabaga Stories, in 1922, followed by Rootabaga Pigeons (1923), and Potato Face (1930). Sandburg also wrote Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, a two-volume biography, in 1926, The American Songbag (1927), and a book of poems called Good Morning, America (1928) in Elmhurst. The Sandburg house at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst was demolished and the site is now a parking lot. The family moved to Michigan in 1930.

Sandburg won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for History for the four-volume The War Years, the sequel to his Abraham Lincoln, and a second Poetry Pulitzer in 1951 for Complete Poems.[13][14][note 1]

In 1945, he moved to Connemara, a 246-acre (100 ha) rural estate in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Here, he produced a little over a third of his total published work and lived with his wife, daughters, and two grandchildren.[15]

On February 12, 1959, in commemorations of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth, Congress met in joint session to hear actor Fredric March give a dramatic reading of the Gettysburg Address, followed by an address by Sandburg.[16]

Sandburg supported the Civil Rights Movement and was the first white man to be honored by the NAACP with their Silver Plaque Award as a "major prophet of civil rights in our time."[17]

Sandburg died of natural causes in 1967 and his body was cremated. The ashes were interred under "Remembrance Rock", a granite boulder located behind his birth house in Galesburg.[18][note 2]

Career

Poetry and prose

Much of Carl Sandburg's poetry, such as "Chicago", focused on Chicago, Illinois, where he spent time as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News and The Day Book. His most famous description of the city is as "Hog Butcher for the World/Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat/Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler,/Stormy, Husky, Brawling, City of the Big Shoulders."

Sandburg earned Pulitzer Prizes for his collection The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg, Corn Huskers, and for his biography of Abraham Lincoln (Abraham Lincoln: The War Years).[14] Sandburg is also remembered by generations of children for his Rootabaga Stories and Rootabaga Pigeons, a series of whimsical, sometimes melancholy stories he originally created for his own daughters. The Rootabaga Stories were born of Sandburg's desire for "American fairy tales" to match American childhood. He felt that the European stories involving royalty and knights were inappropriate, and so populated his stories with skyscrapers, trains, corn fairies and the "Five Marvelous Pretzels".

In 1919, Sandburg was assigned by his editor at the Daily News to do a series of reports on the working classes and tensions among whites and African Americans. The impetus for these reports were race riots that had broken out in other American cities. Ultimately, major riots broke out in Chicago too, but much of Sandburg's writing on the issues before the riots caused him to be seen as having a prophetic voice. A visiting philanthropist, Joel Spingarn, who was also an official of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, read Sandburg's columns with interest and asked to publish them, as The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919.[20][21]

Lincoln works

Sandburg's popular multivolume biography Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, 2 vols. (1926) and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, 4 vols. (1939) are collectively "the best-selling, most widely read, and most influential book[s] about Lincoln."[22] The books have been through many editions, including a one-volume edition in 1954 prepared by Sandburg.

Sandburg's Lincoln scholarship had an enormous impact on the popular view of Lincoln. The books were adapted by Robert E. Sherwood for his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1938) and David Wolper's six-part dramatization for television, Sandburg's Lincoln (1974). He recorded excerpts from the biography and some of Lincoln's speeches for Caedmon Records in New York City in May 1957. He was awarded a Grammy Award in 1959 for Best Performance – Documentary Or Spoken Word (Other Than Comedy) for his recording of Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait with the New York Philharmonic. Some historians suggest more Americans learned about Lincoln from Sandburg than from any other source.[23]

The books garnered critical praise and attention for Sandburg, including the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for History for the four-volume The War Years. But Sandburg's works on Lincoln also received substantial criticism. William E. Barton, who had published a Lincoln biography in 1925, wrote that Sandburg's book "is not history, is not even biography" because of its lack of original research and uncritical use of evidence, but Barton nevertheless thought it was "real literature and a delightful and important contribution to the ever-lengthening shelf of really good books about Lincoln."[24] Historian Milo Milton Quaife criticized Sandburg for not documenting his sources and questioned the accuracy of The Prairie Years, noting they contain a number of factual errors.[22] Others have complained The Prairie Years and The War Years contain too much material that is neither biography nor history, saying the books are instead "sentimental poeticizing" by Sandburg.[22] Sandburg himself may have viewed his works more as an American epic than as a mere biography, a view also mirrored by other reviewers.[22]

Folk music

Sandburg's 1927 anthology the American Songbag enjoyed enormous popularity, going through many editions; and Sandburg himself was perhaps the first American urban folk singer, accompanying himself on solo guitar at lectures and poetry recitals, and in recordings, long before the first or the second folk revival movements (of the 1940s and 1960s, respectively).[25] According to the musicologist Judith Tick:

As a populist poet, Sandburg bestowed a powerful dignity on what the '20s called the "American scene" in a book he called a "ragbag of stripes and streaks of color from nearly all ends of the earth ... rich with the diversity of the United States." Reviewed widely in journals ranging from the New Masses to Modern Music, the American Songbag influenced a number of musicians. Pete Seeger, who calls it a "landmark", saw it "almost as soon as it came out." The composer Elie Siegmeister took it to Paris with him in 1927, and he and his wife Hannah "were always singing these songs. That was home. That was where we belonged."[26]

Film

Sandburg said he considered working on D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916) but his first film work was when he signed on to work on the production of The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) in July 1960 for a year, receiving an "in creative association with Carl Sandburg" credit on the film.[27]

Legacy

Commemoration

Carl Sandburg's boyhood home in Galesburg is now operated by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency as the Carl Sandburg State Historic Site. The site contains the cottage Sandburg was born in, a modern visitor center, and small garden with a large stone called Remembrance Rock, under which his and his wife's ashes are buried.[28] Sandburg's home of 22 years in Flat Rock, Henderson County, North Carolina, is preserved by the National Park Service as the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Carl Sandburg College is located in Sandburg's birthplace of Galesburg, Illinois. During the Spanish-American War, Sandburg was stationed at Camp Alger in Fairfax County, Virginia and so the county has both a Sandburg Road, near the spot where the camp was located, and a Carl Sandburg Middle School.

On January 6, 1978, the 100th anniversary of his birth, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Sandburg. The spare design consists of a profile originally drawn by his friend William A. Smith in 1952, along with Sandburg's own distinctive autograph.[29]

The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) (RBML)[30] houses the Carl Sandburg Papers. The bulk of the collection was purchased directly from Carl Sandburg and his family. In total, the RBML owns over 600 cubic feet of Sandburg's papers, including photographs, correspondence, and manuscripts.[31][32]

In 2011, Sandburg was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[33]

Namesakes

Carl Sandburg Village was a 1960s urban renewal project in the Near North Side, Chicago. Financed by the city, it is located between Clark and LaSalle St. between Division Street and North Ave. Solomon & Cordwell, architects. In 1979, Carl Sandburg Village was converted to condominium ownership.

Numerous schools are named for Sandburg throughout the United States, and he was present at some of these schools' dedications. (Some years after attending the 1954 dedication of Carl Sandburg High School in Orland Park, Illinois, Sandburg returned for an unannounced visit; the school's principal at first mistook him for a hobo.)[citation needed] Sandburg Halls, a student residence hall at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, carries a plaque commemorating Sandburg's roles as an organizer for the Social Democratic Party and as personal secretary to Emil Seidel, Milwaukee's first Socialist mayor.

Carl Sandburg Library opened in Livonia, Michigan, in 1961. The name was recommended by the Library Commission as an example of an American author representing the best of literature of the Midwest. Carl Sandburg had taught at the University of Michigan for a time.[34]

Galesburg opened Sandburg Mall in 1975, named in honor of Sandburg. The Chicago Public Library installed the Carl Sandburg Award, annually awarded for contributions to literature.[35]

Amtrak added the Carl Sandburg train in 2006 to supplement the Illinois Zephyr on the Chicago–Quincy route.[36]

Carl Sandburg Middle School in Alexandria, Virginia, part of Fairfax County Public Schools, was named in honor of Sandburg in 1985.

In other media

- William Saroyan wrote a short story about Sandburg in his 1971 book Letters from 74 rue Taitbout or Don't Go But If You Must Say Hello To Everybody.

- Sandburg's "Sometime they'll give a war and nobody will come" from The People, Yes was a slogan of the German peace movement ("Stell dir vor, es ist Krieg, und keiner geht hin"); however, it is often falsely attributed to Bertolt Brecht.[37]

- Daniel Steven Crafts' The Song and The Slogan is an orchestral composition built around recited passages from Sandburg's "Prairie".

- Peter Louis van Dijk's "Windy City Songs", based on the Chicago poems, was performed by the Chicago Children's Choir and the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Choir in 2007.[38]

- Bob Gibson's "The Courtship of Carl Sandburg", starring Tom Amandes as Sandburg[39]

- In Jonathan Lethem's novel Dissident Gardens the main character Rose Zimmer became an Abraham Lincoln devotee after reading Sandburg's biography. Her copy of the six volumes became the centerpiece of her shrine to Lincoln.

- Sufjan Stevens's "Come on! Feel the Illinoise! Part I: The World's Columbian Exposition Part II: Carl Sandburg Visits Me in a Dream" (from Illinois).

- Composer Phyllis Zimmerman set Sandburg's poems to music in her choral composition Fog, which was recorded and produced on CD.[40]

Bibliography

|

|

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ The Pulitzer Prize for Poetry was inaugurated in 1922 but the organization now considers the first winners to be three recipients of 1918 and 1919 special awards.

- ^ His wife and two daughters would also be interred there. See the signage.

Notes

- ^ a b c Sandburg, Carl (1953). Always the Young Strangers. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 29, 39. Sandburg's father's last name was originally "Danielson" or "Sturm". He could read but not write, and he accepted whatever spelling other people used. The young Carl, sister Mary, and brother Mart changed the spelling to "Sandburg" when in elementary school.

- ^ a b Danilov, Victor (September 26, 2013). Famous Americans: A Directory of Museums, Historic Sites, and Memorials. Scarecrow Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780810891869. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Heitman, Danny (March–April 2013). "A Workingman's Poet". Humanities. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Callahan, North (October 1, 1990). Carl Sandburg: His Life and Works. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0271004860. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg", United States History.

- ^ Sandburg in 1953 was not able to recall his younger self's reasons, but he relates that being able to correctly pronounce "ch" was a mark of assimilation among Swedish immigrants.

- ^ Penelope Niven (August 18, 2012). "American Masters: Carl Sandburg Timeline". PBS. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ Prairie-Town Boy, by Carl Sandburg, 1955. "timforsythe.com" Archived February 16, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ Selected Poems of Carl Sandburg, edited by Rebecca West, 1954

- ^ Carl Sandburg College. "History" Archived February 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ *Mason, Herbert Molloy Jr. (1999). Kolb, Richard K. (ed.). VFW: Our First Century. Lenexa, Kansas: Addax Publishing Group. pp. 13, 90. ISBN 1-88611072-7. LCCN 99-24943.

- ^ a b "Carl Sandburg and the Steichens". January 1998.

- ^ a b "Poetry". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "12 Search Results". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Sandburg Grandchildren - Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Nation Honor Lincoln On Sesquicentennial" (PDF). Yonkers Herald Statesman. Northern Illinois University Libraries. Associated Press. February 11, 1959. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

Congress gets into the act tomorrow, when a joint session will be held. Carl Sandburg, famed Lincoln biographer, will give and address, and actor Fredric March will read the Gettysburg Address.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg cited by NAACP". Baltimore Afro-American. 30 November 1965.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg's ashes placed under Remembrance Rock". The New York Times. 2 October 1967. p. 61.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg House" (PDF). City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. October 4, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- ^ Grossman, Ron (July 19, 2019). "Flashback: Before Chicago erupted into race riots in 1919, Carl Sandburg reported on the fissures". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Sandburg, Carl (1919). The Chicago Race Riots July, 1919. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Hurt, James (Winter 1999). "Sandburg's Lincoln within History". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 20 (1): 55–65.

- ^ Niven, Penelope, Carl Sandburg: A Biography (New York: Scribner's, 1991), p. 536.

- ^ Barton, William E., "Review of The Prairie Years," American Historical Review 31 (July 1926): pp. 809–11.

- ^ Malone, Bill C., and David Stricklin (2003). Southern Music/American Music (University Press of Kentucky, 2003), p. 33.

- ^ Tick, Judith, Ruth Crawford Seeger, A Composer's Search for American Music (Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 57.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg on 20th's 'Greatest'". Variety. July 6, 1960. p. 24. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Historic Site Association". Sandburg.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Scott Catalogue.

- ^ "Rare Book and Manuscript Library". Library.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Papers (Ashville accession)". library.illinois.edu. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Papers (Connemara accession)". library.illinois.edu. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Library Homepage". Livonia.lib.mi.us. 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "October 23 Dinner Honors Allende, Lewis and Sneed". Chicago Public Library. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Amtrak Press Release, October 8, 2006. Amtrak.com.

- ^ "von Brecht?". Die Zeit. August 12, 2004.

- ^ "Nelson Mandela University Choir History". Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "Bob Gibson's 'The Courtship of Carl Sandburg'", lyon.edu. Archived January 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "earthsongs, one world · many voices". earthsongschoralmusic.com. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Sings On WMAQ Today". The Milwaukee Journal. January 10, 1928. Retrieved December 6, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The American Songbag (1927)". Retrieved April 25, 2013.

Further reading

- Niven, Penelope. Carl Sandburg: A Biography. New York: Scribner's, 1991.

- Sandburg, Carl. The Letters of Carl Sandburg. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968.

- Sandburg, Helga. A Great and Glorious Romance: The Story of Carl Sandburg and Lilian Steichen. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

External links

- Carl Sandburg's birthplace in Galesburg, IL (at sandburg.org)

- Carl Sandburg Birthplace, Galesburg, IL (at uncharted101.com)

- Carl Sandburg Home, North Carolina from the National Park Service

- Works by Carl Sandburg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl Sandburg at the Internet Archive

- Works by Carl Sandburg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Day Carl Sandburg Died, PBS American Masters video

- Prayers for the People: Carl Sandburg's Poetry and Songs Archived 2019-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, a Nebraska Educational Telecommunications film, University of Nebraska (video, 1 hour)

- Carl Sandburg databases from the University of Illinois

- Carl Sandburg from the FBI website

- Previously unknown Sandburg poem focuses on power of the gun

- Heitman, Danny (March–April 2013). "A Workingman's Poet". Humanities. 34 (2). National Endowment For The Humanities. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Carl Sandburg at Library of Congress, with 276 library catalog records

- Helga Sandburg at LC Authorities, with 20 records

- Carl Sandburg Home NHS images on Open Parks Network

- Without The Cain and The Derby, a poem by Carl Sandburg: Vanity Fair, May, 1922

- Carl Sandburg at the Internet Broadway Database

- Carl Sandburg at Playbill Vault

Archival materials

- Oliver Barrett-Carl Sandburg Papers Archived 2015-03-09 at the Wayback Machine at Newberry Library

- North Carolina Writers Photographs Collection, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

- Sandburg Series in the Harry Golden papers, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

- Guide to the Carl Sandburg and Ruth Falkenau Correspondence 1919-1930 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- Guide to the Carl Sandburg-Joseph Halle Schaffner Collection 1927-1969 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- Sandburg-Page Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Alan Jenkins (AC 1924) Carl Sandburg Collection at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections