Canadian women in the world wars

Canadian women in the world wars became indispensable because the world wars were total wars that required the maximum effort of the civilian population. While Canadians were deeply divided on the issue of conscription for men, there was wide agreement that women had important new roles to play in the home, in civic life, in industry, in nursing, and even in military uniforms. Historians debate whether there was much long-term impact on the postwar roles of women.

First World War

Pre-war Canadian nursing

Before World War I, Canadian Nursing Sisters participated in the South African War, Boer War, and the War of 1812.[1] Following the creation of the Canadian Army Medical Department in June 1899, the Canadian Army Nursing Service was created and four Canadian nurses were dispatched South Africa.[1] They were granted the relative rank, pay and allowances of an army lieutenant. Before the war was over on May 31, 1902, eight Canadian Nursing Sisters and more than 7,000 Canadian soldiers had volunteered for service in South Africa.

However, World War I allowed women to emerge into the public sphere in an international conflict like never before. When Britain declared war on the German Empire, Canada was automatically compelled to fight alongside Britain. At the beginning of the war, there were five Permanent Force nurses and 57 listed in reserve.[1] Nursing was viewed as a respectable occupation for women because it embodied feminine characteristics such as nurturing, healing, and selflessness.[2] During wartime, nursing became women's primary way of contributing to the war effort and came to represent a distinct form of nationalism on behalf of the Canadian Nursing Sisters. Members of the Overseas C.A.M.C. Nursing Service erected a memorial plaque at St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church (Ottawa) which is dedicated to Matron Margaret H. Smith, R.R.C. & Bar, a veteran of the South African War and the Great War.[3]

First World War nursing and doctoring

On the home front, the Canadian government was actively encouraging young men to enlist in the Royal Forces by enticing them with the promise of adventure in Europe, reminding them of their civil duty. The message propagated by the government to defend and serve resonated with women as well. Essentially, a woman with a nursing certificate held in her hand a ticket to independence and adventure. There was little doubt that the active service posters targeting Canadian men struck nurses more forcibly than messages pleading women to knit furiously and economize the home front.[4] More than any previous opportunity, nursing allowed Canadian women to serve the nation in a way in which they were uniquely qualified. Women joined the war effort with enthusiastic patriotism and a determination to prove their usefulness. By 1917, the Canadian Army Medical Corps (C.A.M.C.) included 2,030 nurses.[5] A total of 3,141 Canadian nurses served in the C.A.M.C. in the First World War.[5] Nurses worked for the notable sum of $4.10 per day while in comparison, their male counterparts fighting on the front lines made about $1.10 a day. With a wage pointedly higher wage than the infantrymen, it was evident that Canadian Nursing Sisters held a very important role on the Western front.

To aid in the war effort, Julia Grace Wales published the Canada Plan, a proposal to set up a mediating conference consisting of intellectuals from neutral nations who would work to find a suitable solution for the First World War. The plan was presented to the United States Congress, but despite arousing the interest of President Wilson, failed when the US entered the war.[7][8]

“In Canada, military nursing was open only to trained nurses, who served at home and overseas as Nursing Sisters with the Canadian Army Medical Corps.”[9] These restrictions affected women who wanted to fulfil their patriotic duty but were not eligible to become a Nursing Sister. There were other ways that women could directly serve in the war through organizations such as the St. John Ambulance Association where they could work as Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses. Over 2,000 women served as VAD's over the course of the great war both at home and in Europe. “3,000 nurses served in the armed forces and 2,504 were sent overseas with the Canadian Army Medical Corps during the First World War.”[10] Nursing Sisters were awarded the rank of an officer which provided them with similar rank and equal pay to men. These nurses were awarded this rank to discourage fraternization with the men and give them authority over their patients.[10] “Voluntary nursing was popularly romanticized due to the legacy of Florence Nightingale.”[11] The view that Canadian society had on war nurses exemplified their beliefs about women's roles. Depicting women in a romanticized way goes to show that working women were not given the same recognition as men due to gender. Despite this inequality in recognition “all uniformed women served as a constant symbol of how reliant wartime society had become on the abilities of women”.[11] Nurses were commonly pictured in propaganda as their uniforms consisting of a white veil with a red cross which symbolizes purity.

During the First World War, there was virtually no female presence in the Canadian armed forces, with the exception of the 3,141 nurses serving overseas and on the home front.[12] Of these women, 328 had been decorated by King George V, and 46 gave their lives in the line of duty.[12] Even though a number of these women received decorations for their efforts, many high-ranking military personnel still felt that they were unfit for the job. Although service in the Great War had not officially been opened to women, they did feel the pressures at home. There had been a gap in employment when the men enlisted; many women strove to fill this void along with keeping up with their responsibilities at home.[12] When war broke out Laura Gamble enlisted in the Canadian Army Medical Corps, because she knew that her experience in a Toronto hospital would be an asset to the war efforts.[6] Canadian nurses were the only nurses of the Allied armies who held the rank of officers.[6] Gamble was presented with a Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class medal, for her show of "greatest possible tact and extreme devotion to duty."[6] This was awarded to her at Buckingham Palace during a special ceremony for Canadian nurses.[6] Health care practitioners had to deal with medical anomalies they had never seen during the First World War. The chlorine gas that was used by the Germans caused injuries that treatment protocols had not yet been developed for. The only treatment that soothed the Canadian soldiers affected by the gas was the constant care they received from the nurses.[6] Canadian nurses were especially well known for their kindness.[6]

Canadians had expected that women would feel sympathetic to the war efforts, but the idea that they would contribute in such a physical way was absurd to most.[12] Because of the support that women had shown from the beginning of the war, people began to see their value. In May 1918, a meeting was held to discuss the possible creation of the Canadian Women's Corps. In September, the motion was approved, but the project was pushed aside because the war's end was in sight.[12]

Women in the workforce

Women working in munitions factories were necessary during WWI as the able-bodied men went overseas to fight. Women worked as ticket collectors, firefighters, bank tellers and even as engineers working with heavy machinery. Though women were completing the same jobs as men, they were being paid lower wages and this inequality led to the first demands for equal pay.[13] Not only did women take up the jobs men left behind, but they also worked to ensure a thriving domestic economy.[14] “Among their working responsibilities, they produced canned food and raised funds to finance hospitals, ambulances, hostels, and aircraft.”[14] 35,000 women worked in the munitions industry in both Ontario and Quebec during this period which for many women was a completely new experience. “The high demand for weapons resulted in the munitions factories becoming the largest single employer of women during 1918.”[15] “For the majority of Canadian women, active participation in the war was restricted to a supporting role on the home front in either non-traditional waged work or as unpaid volunteers in one of the numerous patriotic war relief organizations.”[9] “While women’s participation in paid work garnered praise in some corners of the country, it brought concern or condemnation in others.”[16]

Concerns arose surrounding the issues of motherhood and morality as women entered the workforce, and while women were experiencing new opportunities, this change did not result in society changing its beliefs of gender. “Traditional gender ideology dictated that women required supervision and guidance, and their wartime work did not change that attitude.”[17] Women working was seen as acceptable by society for the time Canada was at war, but once the war was over, working women were expected to give up their jobs and return to the home. Women who were focused on their careers were looked down upon by society whereas girls who were selfless and did not ask for anything more would be rewarded with marriage. Marriage was seen as a goal that all girls should strive for as without a husband, women would not be respected.

Working conditions

Canadian military nurses were well known for their kindness, efficiency, and professional appearance. Canadian nurses worked alongside soldiers on the war front and felt the full effect of wartime risks and death, disease, and the pain was encountered daily by the nurses. Most C.A.M.C. Nursing Sisters served in mobile infirmaries, or Casualty Clearing Stations. These Casualty Clearing Stations, or the C.C.S., as they were titled were typically situated on a railway siding, close to the front lines so they could quickly and efficiently retrieve and treat soldiers who had fallen on the nearby battlefield.[18] The proximity to the fighting exposed the Nursing Sisters to the horrors and dangers particular to the front. The advance areas were often under attack from air raids and shellfire, which frequently placed the lives of the sisters in danger. The Casualty Clearing Stations served as an advanced surgical center that administered emergency surgeries staffed by Canada's most brilliant nurses.[19] One of the most widespread problems the Nursing Sisters had to deal with at the C.C.S. was the vile cases of gangrene.[18] Gangrene, caused by lethal mustard gas getting into an open wound, causing an infection of such toxicity it would literally eat at the skin. Gangrene was such a dreadful problem among Casualty Clearing Stations because the infection spread rapidly making it very hard to contain. This variation of gangrene was certainly not something that the nurses would have been trained on prior to their arrival at a Casualty Clearing Station; however, they were able to treat the infection with much success. The Nursing Sister's role in the efficiency of the Casualty Clearing Stations proved to be a great contribution to the Canadian war effort.

Uniform

In total, 3,141 Canadian nurses volunteered their services for the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. Canadian nurses were the only nurses in the allied armies with the rank of officers and the resemblance of a hierarchical work structure. They were proud of their nursing ranks, reputation on the battlefield, and their distinct uniform. The Canadian nurses sported a familiar uniform consisted of blue dresses and white veils. The Sister Nurses were nicknamed "bluebirds" for the colour of their uniformed, and were identified as members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and also as officers in their nursing units.[6] Their uniforms were held in the highest regard and the nurses wore them with extreme pride, absolutely elated by the unity and importance it symbolized. Their pure white apron and shoulder-length veil gave them the look of nuns or even angels. This linked the imagery of prior religious themes that had promoted authority and femininity and reinforced the 'sister' moniker.[20]

Nursing casualties and realities of war

One of the greatest consequences of the First World War was the number of lives lost, missing, and wounded throughout the entirety of the battles. The Allied and Central powers felt immense casualties and losses with 22,447,500 and 16,403,000 (MIA, KIA, WIA), respectively. Nurses faced this reality throughout the war and even on rare instances, Canadian nurses died while on duty.[21] The most prominent cases of this was the death of four nursing sisters on May 19, 1918, during the bombing raid on No. 1 Canadian General Hospital at Étaples, France, and the death of 14 nursing sisters and over 200 other service personnel on June 27, 1918, when HMHS Llandovery Castle was sunk by the SM U-86.[6] The Llandovery Castle was one of five Canadian hospital ships that served in the First World War. In total, 234 people died with only 24 survivors. The sinking of the Llandovery Castle was one of the most significant Canadian naval disasters of the First World War, in terms of the overall death toll. By the end of the war, 47 Canadian nurses died while on active duty, victims of enemy attack or disease contracted from patients[22] Overall, Canadian nurses dealt with the realities of war and were key assets to the Canadian military and Allied forces.

Women at home

On the Canadian home front, there were many ways in which women could participate in the war effort. Not only did women help raise money; they rolled bandages, knitted socks, mitts, sweaters, and scarves for the men serving overseas. Women raised money to send cigarettes and candy overseas and comfort the fighting men. Canadian women were encouraged to marshal support for the war by persuading wives and mothers to allow their men and sons to enlist. During the war, an immense amount of pressure was laid on women to do their part. One of the women's largest contributions to the war was in the form of voluntary organisations. Through different organisations, women volunteered millions of hours of unpaid labour. One of the biggest organisations that middle-class women participated in was the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire. The IODE strongly advocated imperialist sentiment. By World War I the IODE was of the largest Canadians women's voluntary associations. The IODE organised writing competitions to raise awareness of the war and bring patriotic feeling to Canadian children.[23] Lois Allan joined the Farm Services Corps in 1918, to replace the men who were sent to the front.[24] Allan was placed at E.B. Smith and Sons where she hulled strawberries for jam.[24] Jobs were opened up at factories as well, as industrial production increased.[24] Workdays for these women consisted of ten to twelve hours, six days a week. Because the days consisted of long monotonous work, many women made of parodies of popular songs to get through the day and boost morale.[24] Depending on the area of Canada, some women were given a choice to sleep in either barracks or tents at the factory or farm that they were employed at.[24] According to a brochure that was issued by the Canadian Department of Public Works, there were several areas in which it was appropriate for women to work. These were:

- On fruit or vegetable farms.

- In the camps to cook for workers.

- On mixed and dairy farms.

- In the farmhouse to help feed those who are raising the crops.

- In canneries, to preserve the fruit and vegetables.

- To take charge of milk routes.[25]

In addition, many women were involved in a charitable organization such as the Ottawa Women's Canadian Club, which helped provide the needs of soldiers, families of soldiers and the victims of war.[24] Women were deemed 'soldiers on the home front', encouraged to use less or nearly everything and to be frugal in order to save supplies for the war efforts.[24]

As the Canadian men headed overseas to join the war, the women at home were doing everything in their power to contribute to the war effort and serve their country. “Women’s wartime activities extended far beyond waiting and worrying”[26] and this was evident in the number of women who entered the workforce. While the labour industry saw an influx of female workers taking up the positions men left behind, not all women were able to participate in paid labour. “The majority of Canadian women, particularly if they were middle-class, married, or living in a rural area, made their contribution to the war effort through unpaid voluntary labour for a wide variety of war charities and women’s organizations.”[26] Due to these restrictions, these women were unable to do the same jobs as the women living in densely populated cities. However, though their location or status placed restrictions on them, they did not let this prevent them from doing their part.

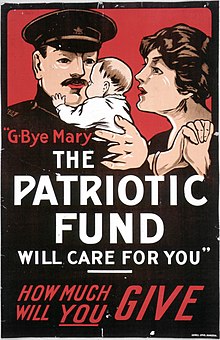

Some of the most well-known organizations are the Canadian Patriotic Fund, the Canadian Red Cross, and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire and these organizations worked to raise money and gather the necessary supplies to send overseas. As members of these charities and organizations, one of the main tasks were helping your neighbours which strengthened the war effort through community and friendship. During this period, women gave up many of life's luxuries because they knew that the war effort was more important. This sacrifice included women giving up old cooking utensils and hair curlers which could be scrapped for metal and rubber to produce war materials. As there were food shortages due to the lack of labour, canning clubs were formed to keep up with the high demand for fruits and vegetables both at home and overseas.[27] Along with food shortages, rationing was also set in place which created challenges for women in the kitchen. To make cooking easier during this time, women created and published special cookbooks that manipulated recipes to accommodate the restrictions.[27] Farm women now had to take over the responsibilities of the farm now that their husbands, sons, and farmhands were all overseas fighting. Farm work was now done by women as the demand for food production increased which had women planting, harvesting, and caring for the livestock on their farms.

Women of the Six Nations

Indigenous women were also donating their time and effort to supporting the war. A group of women from the Six Nations Grand River reserve established the Six Nations Women's Patriotic League in 1914 where they knitted socks and contributed to the war effort.[28] As Canada was still under the dominion of the British, this meant that when Britain declared war on Germany in 1914, Canada went with. These women were motivated to support the Great War due to the “Iroquois tradition of loyalty to Britain and the supportive role that Iroquois women had played during wartime in the past”.[28] The traditional work that Iroquois women performed during wartime was taking care of the home and children while also ensuring that their men had the necessities for war. The work that these Indigenous women were doing was reflective of the work women across Canada were doing, which shows that despite their beliefs and values, both groups felt their effort was necessary. Along with Indigenous women, young girls were also doing their part by making handmade items to send to the soldiers overseas.[29] “The first and only woman from the Six Nations to enlist in the military during the Great War was Edith Anderson Monture, who served overseas as a Nursing sister.”[30] Once her training was complete, Monture travelled overseas to France in 1918 and served as a Nursing Sister for more than a year. The diary Montour kept while serving overseas was published by her family and it “reveals that her experiences paralleled those of non-Native Canadian nurses in the war”.[31] The Six Nations Women's Patriotic Fund did not only support Canadian troops, but they also knitted socks and other supplies for Belgian Relief. They did this to provide support to Belgian refugees who were starving and displaced due to the invasion of Belgium by Germany.

Female university students

Female students and faculty at the University of Toronto went through drastic changes when the Great War broke out. As the men on campus “began conducting loud, highly visible, two-hour-long military drills” the women gathered to discuss what roles they would play during this time of war.[32] Classes would end earlier than usual to allow for students and staff to fulfil their patriotic duties. The women would use this time to knit, sew, and collect any materials which could be used by soldiers and nurses. “U of T women also raised funds to support hospitals overseas”[33] Community dances became a popular form of fundraiser due to their lighthearted nature and offering of a place where people could forget about the war for a short amount of time. To encourage more women to join these collective fundraising groups, motivational speakers were brought to the university where they promoted specific roles. Where male students were academically rewarded for their participation in the war, “female students pursued their war work without reward or compensatory recognition on the assumption that, for women, virtue and self-sacrifice were both patriotic duties and their own reward”.[34]

Societal expectations

During the first world war, the belief that a woman's position was to be in the home taking care of both the husband and children was very prominent. This was due to the influence of both the Victorian and Edwardian time periods on society and the economy.[26] However, the question of what women's work actually was became more prominent by WWI as women were taking up roles that were previously thought to be exclusively for men. “Nursing was traditionally seen as the natural province of women, but the emerging nursing profession (which relied on hospital training as the standard that protected it from being diluted by untrained outsiders) resisted the rush of ordinary women to its ranks.”[35] Society reacted questioningly to women moving into paid labour, unsure of if it was appropriate for women to be doing the same work as men. Society was slowly moving in a direction that saw women working which altered beliefs about women in childcare and the home. “The women and girls of Canada and Newfoundland who lived through the Great War may not have experienced a transformation in society’s thinking about their appropriate workplace roles on a scale equivalent to that of their daughters and granddaughters in the Second World War, but they nonetheless encountered a wartime society that loosened its hold on some boundaries even as it clung tightly to others.”[36]

Family

Women's lives were greatly altered by World War I in aspects of both their home life and social life. “Wives, mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, cousins, daughters, friends, girlfriends, and fiancées faced altered social, cultural, political, and economic landscapes in the wake of their loved ones’ departures.”[37] The effect that the absence of men had on women’s experiences was large as new opportunities arose. Women were now working in the jobs left behind by men serving in the armed forces which was a change from their usual roles in the home. As the war continued on, women had to rise to the challenges that came with Canada being at war, all of which were brand new experiences. The absence of men caused economic changes in the family as well considering the man of the house was in charge of all financial issues. Without male wages, families had to rely on the network of neighbours and extended family to get by during this time. Young girls were invested in the news of the war constantly wanting information on what was happening overseas as their fathers and brothers were fighting. Young girls wanted to do their part as well in the war effort and participated in clubs and groups which raised funds for the war. “The Girl Guides collected money for the Canadian Patriotic Fund and other social support agencies.”[38]

Motherhood

“Motherhood throughout the nineteenth century had been deemed the fundamental role of Canadian women.”[39] During the war, motherhood was seen as more than just caring for others, it was seen as “the moral character of the nation”.[40] The use of motherhood in a political sense helped to unite the people of Canada as the country entered the war alongside Britain. Many poems and stories were published that compare a nurturing mother with the country to ignite feelings of patriotism and community in people. The symbol of motherhood in relation to the Great War had shifted from the empire to include the responsibility women had towards her children and family. “Perhaps the ultimate sacrifice that a woman could make for her country was to have her child die in uniform.”[41]

Suffrage

Women's suffrage in Canada took off during the First World War. As many men were overseas in the trenches, women entered the workforces and gained new responsibilities on the home front. As well, wealthy highly educated and Canadian-born white women began to question why poor, illiterate immigrant men could vote when they could not. The suffrage movement met opposition by men and the Catholic Church, who believed that women were ill-suited for politics and that women leaving the home would break up the traditional family. This opposition was most prominent in Quebec, where the Catholic Church had great influence on society. The church vigorously opposed women's right to vote as they believed that women leaving the home would lead to poorly raised children. Women in Quebec were not granted the right to vote provincially until 1940, 18 years after the last other province (PEI) had grant women voting rights. (Newfoundland had granted voting rights to women in 1925 but did not join Canada until 1949.) The right to vote in provincial elections was granted to women between 1916 and 1940 (see below for statistics).[42]

Provincial vote:

- Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta: 1916

- Ontario, British Columbia: 1917

- Nova Scotia, New Brunswick: 1918, 1919

- Prince Edward Island: 1922

- Newfoundland: 1925[43] –– Newfoundland was an independent Dominion until 1949 when it joined the Canadian federation as a province. The name of the province was changed to Newfoundland and Labrador in 2001.

- Quebec: 1940.

Women were granted voting rights on the same basis as men – and denied them likewise – status Indians and some Asians were denied the right to vote until as late as the 1960s.[44]

Women's federal voting rights changed in 1917 with the Wartime Elections Act. This act granted voting rights to women with relatives in the military. This act was a huge step for the suffrage movement in Canada. And in 1919 the Act to Confer the Electoral Franchise upon Women was passed granting women the right to vote federally.[45]

“By 1914, women had successfully pressured politicians to enact important legislation in areas such as public health and child labour.”[26] These advancements helped to bring forth the issues of women's suffrage and new forms of paid work. As Canadian women did their part in supporting the war, they did not forget about their previous desire to earn the right to vote. In 1917 the Wartime Elections Act was passed which granted the right to vote to women who had served in the armed forces or had close ties to a man who served. “In fact, the cause of universal woman suffrage was considerably advanced in 1916 when the western provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta gave women the provincial franchise, and again in 1917, when British Columbia and Ontario did likewise.”[26] Though women received the right to vote, there were still many issues to be dealt with about the roles of Canadian women in society. As the war had ended, working women were expected to give up their positions as men came home and resume the roles they had before the war. Even though “women’s skills, determination, and labour had contributed tremendously to the functioning of Canadian society during the Great War”, they were not seen as necessary in the workforce.[26]

Gender norms

Though many things had changed over the course of the war for women, conventional gender norms were being reinforced in society. Many men came home with injuries that would leave them disabled for the rest of their lives. This meant that they would no longer be able to take care of their families as they once did, leaving women to be the figurative head of the house. The wives and daughters now had to care for these disabled men which went against the beliefs society had about traditional gender norms. The man of the house was supposed to be the one providing for his family, but many were now physically unable to. Though women now had more power in the house, traditional society still placed men over women. Many novels were written about disabled soldiers after the war by men who tended to flatten the representation of women, consigning them to one of three stereotypical roles: mothers, lovers, or nurses”.[46] Conventional gender norms were still very much prominent after the war which diminished the work and effort women did. Though women made a large impact on the wartime economy and proved that they could be both good workers and still care for their families, they would not get the recognition they deserved for a long time after the war had ended.

Commemoration

In 1919, the construction of the World War I Canadian nurses memorial began under the direction of artist G.W. Hills. The Nursing Sisters' Memorial is located in the Hall of Honour in the centre block of the Parliament Buildings on Parliament Hill, Wellington Street, Ottawa. In a preliminary ceremony on Parliament Hill, in front of the centre block, the President of the Association, Miss Jean Browne, presented the memorial to the acting Prime Minister, Sir Henry Drayton, who accepted it in the name of the people of Canada.[47] The finished sculpture consists of three components supporting the main theme of the heroic service of nursing sisters from the founding of Hôtel Dieu in Quebec City in 1639 to the end of the First World War.[48] The monument was finalized and unveiled in 1926, to commemorate the significance of Canadian nurses during World War I.

A number of artists have sought to memorialize the contribution of Canadian women in all aspects of the war effort. Canadian artist Marion Long sought to demonstrate the home front from the perspective of women and housewives, using charcoal to document moments ranging from time at the public market to moments of pain and loss upon a killed-in-action notification.[49] H. M. May studied the thousands entering the workforce for the first time to create famous works like Women Making Shells, a 1919 oil painting dedicated to the labour of female factory workers.[49]

Second World War

Obligation to fight

When Canada declared war in 1939, women felt obligated to help the fight. In October 1938, the Women's Volunteer Service was established in Victoria, British Columbia. A recruitment event was held in hopes of gaining around 20 new volunteers; over 100 women arrived to join the efforts.[12] Shortly after, more British Columbian women felt the need to do their part, and when the 13 corps joined together, and the B.C. Women's Service Corps was created. Soon after, all the other Canadian provinces and territories followed suit and similar volunteer groups emerged. "Husbands, brothers, fathers, boyfriends were all joining up, doing something to help win the war. Surely women could help as well!" In addition to the Red Cross, several volunteer corps had designed themselves after auxiliary groups from Britain. These corps had uniforms, marching drills and a few had rifle training. It soon was clear, that a unified governing system would be beneficial to the corps. The volunteers in British Columbia donated $2 each to pay the expenses so a representative could talk to politicians in Ottawa. Although all of the politicians appeared sympathetic to the cause, it remained 'premature' in terms of national necessity.[12]

Canada was later in granting this permission than the rest of the Commonwealth. The British Mechanized Transport Corps had begun to see the women of Canada as a great asset to the war effort, and began to look into the recruitment of these women for their purposes. In June 1941, they were officially given permission to recruit women in Canada for overseas duty. It quickly became apparent that it would look very odd for the British to be recruiting in Canada when, no there was no corresponding Canadian service. However, many of the women who were active in the various volunteer corps did not meet the requirements to be enlisted women. The majority of these women were older than the accepted age, would not pass the fitness test, or had physical or medical impairments. It was quickly realized that the women needed had jobs and were not free to join.[12]

Women at home

Women's participation on the home front was essential to the war effort. Leading into the Second World War, the 'breadwinner model' indicated that married women belonged in the home, with men working. Men were supposed to work and play in the public domain with the private realm supposedly being the domain of women.[23] The outbreak of World War II forced society to rethink women's role outside of the home. The largest contribution by the majority of Canadian women was through unpaid volunteer work, through their domestic abilities and skills; women were able to support the nation and the war effort. The government called upon women to participate in volunteer programs. Women began collecting recycled items such as paper, metal, fat, bones, rags, rubber, and glass. Clothing was also collected by Canadian women for free distribution overseas. They also prepared care packages to send to the men and women overseas. Canadian women were responsible for maintaining the morale of the nation. All over Canada, women responded to demands made upon them by not only selling war savings stamps and certificates but purchasing them as well, and collecting money to by bombers and mobile canteens.[50] If you were a young unattached woman in 1939, the war offered unprecedented opportunities on the home front. Young women were given a chance to move away from home, go to parties and dances in the name of patriotic duty.

Women in the workforce

Factory work

When men left their factory jobs to fight overseas, women stepped up to fill their positions in mass. These jobs became essential during the war when munitions supplies became vital to the war effort. Women excelled in these historically male-dominated roles. Some conservative protesters, rallied against women leaving the home as they argued this would hurt the traditional family ideals. This was especially true in Quebec, where the strong-arm of the Catholic Church kept many women from working outside the home. The government supported this new essential workforce by creating the first government run daycares. Though women shined in these positions and were even recruited in industrial communities, the jobs remained extremely gendered and women were expected to leave the factories when veterans returned home. Women's work in factory during the second war is the most important role played by women on the home front.[42]

Women and childcare

Women in the workforce meant that working mothers needed access to childcare. In anticipation of mothers in the workforce, the Federal Minister of Labour was empowered to enter into agreements for the establishment of daycare facilities for the children of mothers working in war industries. From 1942 to 1946, the Dominion-Provincial Wartime Agreement allowed for subsidized day nursery care for mothers working in essential wartime industries. Provinces that were most industrialized, such as Ontario and Quebec, saw a growing demand for this type of service and took advantage of this agreement to establish their own standards and regulations. This program provided aid to mothers working in war industries; however, it placed strict limitations similar services for women with young children in other work sectors.[51] These wartime day nurseries boasted organized play, frequent outings and other features that would become early childhood education. In June 1946, with the war in Europe over, Federal funding for day nurseries was pulled and the majority of day nurseries were closed. However, some municipalities continued offering day care services and made up the shortfall.[52]

Canadian Women's Army Corps

In June 1941, the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWAC) was established. The women who enlisted took over

- Drivers of light mechanical transport vehicles

- Cooks in hospitals and messes

- Clerks, typists, and stenographers at camps and training centers

- Telephone operators and messengers

- Canteen helpers[12]

The CWAC was officially established on August 13, 1941, and by war's end, it had some 21,000 members. Women trained as drivers, cooks, clerks, typists, stenographers, telephone operators, messengers, and quartermasters.[53] However, these duties would expand to include more traditionally male jobs such as driving trucks and ambulances, and working as mechanics and radar operators. While most CWACs served in Canada, three companies of female soldiers were posted overseas in 1943.[53] Ottawa sent the companies into north-west Europe, mainly to act as clerks with headquarters units. Only 156 CWACs served in north-west Europe, and 43 in Italy, before the Germans surrendered in 1945.[53] In the months following the Allied victory, hundreds more CWACs served in Europe working on the complex task of repatriating the army to Canada. Others served with Canadian occupation forces in Germany. In all, approximately 3000 served Canada overseas. While no members of the CWAC were killed due to enemy action, four were wounded in a German V-2 missile attack on Antwerp in 1945.[53]

Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service

An element of the Royal Canadian Navy, the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) was active during the Second World War and post-war years. This unit was part of the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve until unification in 1968.[54] The WRCNS (or "Wrens") was modelled on the Women's Royal Naval Service, which had been active during the First World War and then revived in 1939. The Royal Canadian Navy was slow to create a women's service, and established the WRCNS in July 1942, nearly a year after the Canadian Women's Army Corps and the Royal Canadian Air Force Women's Division.[55] By the end of the war however nearly 7,000 women had served with the WRCNS in 39 different trades.[56] The WRCNS was the only corps that was officially a part of their sanctioning body as a women's division.[citation needed][clarification needed] This led to bureaucratic issues that would be solved most easily by absorbing the civilian corps governed by military organizations, into women's divisions as soldiers.

Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force and RCAF Women's Division

The Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF) was formed in 1941 as an element of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Changing to the Women's Division (WD) in 1942, this unit was formed to take over positions that would allow more men to participate in combat and training duties. The original 1941 order-in-council authorized "the formation of a component of the Royal Canadian Air Force to be known as the Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force, its function being to release to heavier duties those members of the RCAF employed in administrative, clerical and other comparable types of service employment."[57] Among the many jobs carried out by WD personnel, they became clerks, drivers, fabric workers, hairdressers, hospital assistants, instrument mechanics, parachute riggers, photographers, air photo interpreters, intelligence officers, instructors, weather observers, pharmacists, wireless operators, and Service Police. Although the Women's Division was discontinued in 1946 after wartime service, women were not permitted to enter the RCAF until 1951.[58]

According to the RCAF the following are the requirements of an enlisted woman:

- Must be at least 18 years of age, and younger than 41 years of age

- Must be of medical category A4B (equivalent of A1)

- Must be equal to or over 5 feet (152 cm), and fall within the appropriate weight for her height, not being too far above or below the standard.

- Must have a minimum education of entrance into high school

- Be able to pass the appropriate trades test

- Be of good character with no record of conviction for an indictable offence[12]

Women would not be considered for enlistment:

- If they hold permanent Civil Service appointments

- If they are married women who have children dependent on them for care and upbringing (i.e. Sons under 16 years and daughters under 18 years)

On July 2, 1941, the Women's Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was created.[59] By the end of the war it totalled some 17,000 members. The RCAF did not train their female recruits to be flying instructors or combatants, although their direct spirit of participation is best described by the division's slogan, "We serve that men may fly".[59] They were initially trained for clerical, administrative and support roles. As the war continued, however, women would also work in other positions like parachute riggers and laboratory assistants, and even in the very male-dominated electrical and mechanical trades. Many RCAF-WD members were sent to Great Britain to serve with Canadian squadrons and headquarters there.[59]

Pre-war nursing

By 1940, Canada's healthcare system had undergone a fundamental overhaul. At the beginning of the war Canadian military began to actively recruit women into sectors of employment previously dominated by men.[60] Military administrators looked to find new ways to radically increase the available pool of trained nurses. In an effort to keep nursing a predominantly female industry and an attractive occupational option, propaganda to recruit women into the war effort forced nurses to abandon the long-held Victorian ideal of femininity. Tailored shirts, short sleeves, and relaxed necklines all assisted in the development in a new era of nursing personnel.[61]

Second World War nursing

Despite a large shift in the profession, Second World War nurses nonetheless joined the military with great numbers. Whereas previous Nursing Sisters had been members of the Canadian Expeditionary force attached to the British army, nurses in the Second World War were fully integrated into the Canadian Army Medical Corps, the Royal Canadian Air Force Medical Branch, and the Royal Canadian Naval Medical Service.[62] In total 4079 military nurses served during the Second World War, comprising the largest group of nurses in Canadian military history.[62] With few exceptions, Nursing Sisters served within Canadian medical units and wherever Canadian troops went throughout England, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, North Africa, Sicily and Hong Kong.[63] As the nursing profession itself became more professionalized, military nursing followed suit. Professional nurses serving in the R.C.A.M.C included laboratory technicians, therapists, dieticians, and physiotherapists.[63]

Working conditions

Although World War II was fought with very different weapons and tactics than the First World War, Nursing Sisters served in similar ways and the atrocities they faced were of the same horrendous nature. Whereas most Casualty Clearing Stations were situated near the front lines in World War I, hospitals in World War II were placed near land-based naval bases.[64] Royal Canadian Nurses served primarily at nine of these hospital bases. Their strategic relation to German submarine and U-Boat activity was where the majority of casualties occurred to merchant seaman during the Battle of the Atlantic. The two Canadian hospital ships the Lady Nelson and the Letitia actually belonged to the R.C.A.M.C and were staffed entirely by Canadian nurses.[65]

Legacy

The Second World War extended well beyond the May 1945 armistice for Canadian nurses. Canadian nurses stayed in Europe and contented to care for recovering casualties, civilians, and concentration camps through late 1946.[66] The end of the Second World War brought the closure of military and station hospitals across Canada. A total of 80 nurses, 30 RCAMC, 30 RCAF and 20 RCN sisters joined the permanent force and served at military establishments across the country; many more staffed the Department of Veterans Affairs' hospitals to care for hundreds of returning Veterans.[67]

Recruitment and training

Training centres were required for all of the new recruits. They could not be sent to the existing centres as it was necessary that they be separated from male recruits. The Canadian Women's Army Corps set up centres in Vermilion, Alberta, and Kitchener, Ontario. Ottawa and Toronto were the locations of the training centres for the Canadian Women's Auxiliary Air Force. The Wrens were outfitted in Galt, Ontario. Each service had to come up with the best possible appeal to the women joining, for they all wanted them. In reality, the women went where their fathers, brothers and boyfriends were.[12]

Women had numerous reasons for wanting to join the effort; whether they had a father, husband, or brother in the forces, or simply felt the patriotic duty to help. One woman exclaimed that she could not wait to turn eighteen to enlist, because she had fantasies of assassinating Adolf Hitler.[12] Many women lied about their age to enlist, usually girls around the age of 16 or 17. A few girls made it through between the ages of 12 and 15, not unknown to their fellow recruits, as a couple even brought their teddy bears to basic. The United States would only allow women to join who were at least 21, so many considered going to Canada. Recruitment for the different branches of the Canadian Forces was set up in places like Boston and New York. Modifications were made to girls with US citizenship, having their records marked, "Oath of allegiance not taken by virtue of being a citizen of the United States of America."[12] Interested women were encouraged not to give up their current employment until their acceptance was confirmed by the respective military group, as they may not meet the strict entrance requirements. Women were obligated to conform to the same enlistment requirements as men. They had to adhere to medical examinations, and fitness requirements as well as training in certain trades depending on the aspect of the armed forces they wanted to be a part of. Enlisted women were issued entire uniforms minus the undergarments, which they received a quarterly allowance for.[12]

To be an enlisted woman during the creation stages was not easy. Besides the fact that everyone was learning as they went, they did not receive the support they needed from the male recruits. Women were initially paid two-thirds of what a man at the same level made.[68] As the war progressed the military leaders began to see the substantial impact the women could make. In many cases the women had outperformed their male counterparts. This was taken into account and the women received a raise to four-fifths of the wages of a man.[68] A female doctor however, received equal financial compensation to her male counterpart. One commander argued that it would be impossible for female recruits to reach the location of his station, even though it was located only three and a half miles from the city and was serviced by a paved road and a bus route The negative reaction of men towards the female recruits was addressed in propaganda films. Proudly She Marches and Wings on Her Shoulder were made to show the acceptance of female recruits, while showing the men that although they were taking jobs traditionally intended for men, they would be able to retain their femininity.[12]

Other problems faced early on for these women were that of a more racial stature. An officer of the Canadian Women's Army Corps had to write to her superiors regarding whether or not a woman of "Indian nationality" would be objected for enlistment. Because of Canada's large population of immigrants, German women also enlisted creating great animosity between recruits.[12] The biggest difficulty was however the French-Canadian population. In a document dated 25 November 1941, it was declared that enlisted women should 'unofficially' speak English. However, seeing the large number of capable women that this left out, a School of English was stabled for recruits in mid-1942.[12]

Once in training, some women felt that they had made a mistake. Several women cracked under the pressure and were hospitalized, while others took their own lives. Other women felt the need to escape, and simply ran away. The easiest and fastest ticket home however was pregnancy.[12] Women who found out that they were pregnant were given a special quickly executed discharge.[12]

The women who successfully graduated from training had to find ways to entertain themselves to keep morale up. Softball, badminton, tennis, and hockey were among popular pastimes for recruits.[12]

Religion was of a personal matter to the recruits. A minister of sorts was usually on site for services. For Jewish girls, it was custom that they were able to get back to their barracks by sundown on Sabbath and holidays; a rabbi would be made available if possible.[12]

At the beginning of the war 600,000 women in Canada held permanent jobs in the private sector, by the peak in 1943 1.2 million women had jobs.[69] Women quickly gained a good reputation for their mechanical dexterity and fine precision due to their smaller stature.[69] At home a woman could work as:

- Cafeteria workers

Women working at the General Engineering Company (Canada) munitions factory - Loggers or lumberjills

- Shipbuilders

- Scientists

- Munitions workers[68]

Women also had to keep their homes together while the men were away. "An Alberta mother of nine boys, all away at either war or factory jobs – drove the tractor, plowed the fields, put up hay, and hauled grain to the elevators, along with tending her garden, raising chickens, pigs, and turkeys, and canned hundreds of jars of fruits and vegetables."[69]

In addition to physical jobs, women were also asked to cut back and ration. Silk and nylon were used for the war efforts, creating a shortage of stockings. Many women actually painted lines down the back of their legs to create the illusion of wearing the fashionable stockings of the time.[69]

References

- ^ a b c "The Nursing Sisters of Canada – Women and War – Remembering Those Who Served – Remembrance – Veterans Affairs Canada". Veterans.gc.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ Quinn 2010, p. 23.

- ^ "Matron Margaret H. Smith Memorial: Memorial 35059-145 Ottawa, ON". National Inventory of Canadian Military Memorials. Veterans Affairs Canada. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Quinn 2010, p. 34.

- ^ a b "Canada's Nursing Sisters". Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Library and Archives Canada, Government of Canada (7 November 2008). "Canada and the First World War: We Were There".

- ^ "Julia Grace Wales suggests an influential proposal to end the war, 1915". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ^ Randall 1964, pp. 162–163.

- ^ a b Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 99

- ^ a b "World War Women | Canadian War Museum".

- ^ a b Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 116

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Gossage 2001.

- ^ "World War I: 1914-1918 | Striking Women".

- ^ a b "Canadian Women and War | the Canadian Encyclopedia".

- ^ "World War I: 1914-1918 | Striking Women".

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 148

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 158

- ^ a b Wallace, Cuthbert (1915). "The Position of Casualty Clearing Stations". The British Medical Journal. 2 (2866): 834–836. JSTOR 25315460.

- ^ Nicholson 1975, p. 80.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart & Toman2009, p. 26.

- ^ Glassford and Shaw (2012). A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland During the First World War. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 9780774822572.

- ^ "The Canadian Encyclopedia". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ a b Francis et al. 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Library and Archives Canada, “Canada and the First World War: We Were There,” Government of Canada, 7 November 2008

- ^ Canada, Department of Public Works, Women’s Work on the Land, (Ontario, Tracks and Labour Branch)

- ^ a b c d e f "Women's Mobilisation for War (Canada) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)".

- ^ a b "Canada Remembers Women on the Home Front - Women and War - Remembering those who served - Remembrance - Veterans Affairs Canada". 8 August 2019.

- ^ a b Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 29

- ^ "Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada". 25 May 2021.

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 34

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 35

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 81

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 82

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 85

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 100

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 100-101

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 171

- ^ "The Home Front - the Children's War".

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 270

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 271

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 285

- ^ a b Conrad & Finkel 2008.

- ^ Duley, Margot I. (1993). Where once our mothers stood we stand : women's suffrage in Newfoundland, 1890-1925. Charlottetown, P.E.I.: Gynergy. ISBN 0-921881-24-X. OCLC 28850183.

- ^ Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ "Women Get the Vote". Canada History. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014. Page 294

- ^ "The Nursing Sisters' Memorial – Memorials In Canada – Memorials – Remembrance – Veterans Affairs Canada". Veterans.gc.ca. 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ "The House of Commons Heritage Collection". Parl.gc.ca. 1926-08-24. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ a b Brandon, Laura (2021). War Art in Canada: A Critical History. Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0271-5.

- ^ Bruse, Jean. Back in the Attack: Canadian women during the Second World War at Home and Abroad. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada 1985.

- ^ Pierson, Ruth Roach. "Canadian Women and the Second World War". On all Fronts. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "Daycare during wartime". CBC Archives.

- ^ a b c d The Canadian War Museum. "The Canadian Women's Army Corps, 1941–1946". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "WRCNS". Navalandmilitarymuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ "Serving Their Country: the Story of the Wrens, 1942–1946". Journal.forces.gc.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ Ziegler 1973, p. 6.

- ^ "The Royal Canadian Air Force Women's Division". Juno Beach. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan 2005, chpt. Royal Canadian Air Force Womens Division.

- ^ McPherson 1996, p. 96.

- ^ McPherson 1996, p. 100.

- ^ a b Bates2005, p. 172.

- ^ a b Bates2005, p. 173.

- ^ Bates2005, p. 174.

- ^ Bates2005, p. 178.

- ^ Bates2005, p. 175.

- ^ Bates2005, p. 177.

- ^ a b c "1942 Timeline". WW2DB. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ^ a b c d Veterans Affairs Canada, “Women at War,” Archived 2013-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Government of Canada,19 October 2012

Bibliography

- Bates, Christina, ed. (2005). On All Frontiers: Four Centuries of Canadian Nursing. Canadian Museum of Civilization, University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 9780776605913.

- Conrad, Margaret; Finkel, Alvin (2008). History of the Canadian Peoples: 1867 to the Present, Vol. 2 (5th ed.). Pearson Canada. ISBN 9780321539083.

- Francis, R. Douglas; Smith, Donald; Jones, Richard; Wardhaugh, Robert A. (2011). Destinies: Canadian History Since Confederation (7th ed.). Nelson Education Limited. ISBN 9780176502515.

- Elliott, Jayne; Stuart, Meryn; Toman, Cynthia, eds. (2009). Place and Practice in Canadian Nursing History. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774858663.

- Gossage, Carolyn (2001). Greatcoats and Glamour Boots: Canadian Women at War (1939-1945). Dundurn. ISBN 9781550023688.

- McPherson, Kathryn M. (1996). Bedside Matters: The Transformation of Canadian Nursing, 1900-1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195412192.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L (1975). Canada's nursing sisters. Hakkert. ISBN 978-0888665676.

- Quinn, Shawna M. (2010). Agnes Warner and the Nursing Sisters of the Great War. Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 9780864926333.

- Randall, Mercedes Moritz (1964). Improper Bostonian. Ardent Media.

- Ziegler, Mary (1973). We Serve That Men May Fly. The Story of the Women's Division Royal Canadian Air Force. R.C.A.F. ( W.D. ) Association.

- The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina, Canadian Plains Research Center. 2005. ISBN 9780889771758.

Further reading

- Ciment, James; Thaddeus Russell (2007). The Home Front Encyclopedia: United States, Britain, and Canada in World Wars I and II. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-849-5.

- Latta, Ruth (1992). The Memory of All That: Canadian Women Remember World War II. GeneralStore PublishingHouse. ISBN 978-0-919431-64-5.

- Pierson, Ruth Roach (1986). They're Still Women After All: The Second World War and Canadian Womanhood. McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 9780771069581.

- Simpson, Suzanne; Toole, Doris; Player, Cindy (1979). Women in the Canadian Forces: Past, Present and Future (in English and French). Atlantis. pp. 267–283.

- Symons, Ellen (June 1991). "Under Fire: Canadian Women in Combat". Canadian Journal of Women & the Law. 4 (2).[dead link]

External links

- Glassford, Sarah: Women's Mobilisation for War (Canada), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Bishop Stirling, Terry: Women's Mobilization for War (Newfoundland), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.