Cabinet painting

A cabinet painting (or "cabinet picture") is a small painting, typically no larger than two feet (0.6 meters) in either dimension, but often much smaller.[5] The term is especially used for paintings that show full-length figures or landscapes at a small scale, rather than a head or other object painted nearly life-size. Such paintings are done very precisely, with a great degree of "finish".[6]

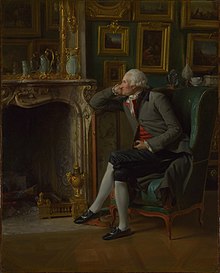

From the fifteenth century onward, wealthy collectors of art would keep these paintings in a cabinet, which was a relatively small and private room (often very small even in large houses) to which only those with whom they were on especially intimate terms would be admitted. A cabinet, also known as a closet, study (from the Italian studiolo), office, or by other names, might be used as an office or just a sitting room. Heating the main rooms in large palaces or mansions in the winter was difficult, so small rooms such as cabinets were more comfortable. They offered more privacy from servants or other household members and visitors. Typically, a cabinet would be for the use of a single individual; a large house might have at least two (his and hers) and often more.

Later, cabinet paintings might be housed in a display case, also known as a cabinet, but the term cabinet arose from the name (originally in Italian) of the room, not the piece of furniture. Other small and precious objects, including miniature paintings, "curiosities" of all sorts (see cabinet of curiosities), old master prints, books, or small sculptures might also be displayed in the room.

A rare example of a surviving cabinet with its contents probably little changed since the early eighteenth century is at Ham House in Richmond, London. It is less than ten feet square, and leads off from the Long Gallery which is over a hundred feet long and twenty feet wide, giving a rather startling change in scale and atmosphere. As is often the case, it has a view of the front entrance to the house, so that passersby and daily activities can be observed. Most surviving large houses or palaces, especially from before 1700, have such rooms, but they are often not displayed or accessible to visitors.

The magnificent Mannerist Studiolo of Francesco I Medici in Florence is larger than most examples and rather atypical in that most of the paintings were commissioned for the room.

There is an equivalent type of small sculpture, usually bronzes. The leading exponent in the late Renaissance was Giambologna, who produced sizeable editions of reduced versions of his large works, and also made many exclusively in small scale.[7] These sculptures were designed to be picked up and handled, even fondled. Small antiquities were also very commonly displayed in such rooms, including rare coinage.

Small paintings have been produced during all periods of Western art, but some periods and artists are especially noticeable for them. Raphael produced many cabinet paintings, and all the paintings of the important German artist Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610) could be so described. The works of these two were much copied. The Dutch artists of the seventeenth century had an enormous output of small paintings. The painters of the Leiden School were especially noted "Fijnschilders" or "fine painters" producing highly finished small works. Watteau, Fragonard and other French 18th-century artists produced many small works, generally emphasizing spirit and atmosphere rather than a detailed finish. In modern times the term is not as common as it was in the 19th century, but remains in use among art historians.

A "cabinet miniature" is a larger portrait miniature, usually full-length and typically up to about ten inches (25cm) high. These were first painted in England, from the end of the 1580s, initially by Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver.[8]

In 1991, an exhibition entitled "Cabinet Painting" toured London, Hove Museum and Art Gallery and Glynn Vivian Art Gallery and Museum, Swansea. It included more than sixty cabinet paintings by contemporary artists.

References

- ^ C. B. Bailey: The Age of Watteau, Chardin and Fragonard – Masterpieces of French Genre Painting, Exhibition calalogue, Ottawa, Washington and Berlin, 2003–04, cat. No. 105, reproduced p. 335, discussed pp. 334 and 375

- ^ Paul Gallois: Baron de Besenval’s eclectic eye, The Furniture History Society, London, Newsletter 221, February 2021, p. 3

- ^ C. B. Bailey: Conventions of the Eighteenth-Century Cabinet de Tableaux: Blondel d' Azincourt's La Première idée de la curiosité, CAA, The Art Bulletin, vol. LXIX, no. 3, September 1987, p. 440, reproduced p. 12

- ^ Luc-Vincent Thiéry: Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, ou Description raisonnée de cette Ville, de sa Banlieue, et de tout ce qu'elles contiennent de remarquable, tome II, chapitre 'Hôtel de M. le Baron de Besenval,' Libraire Hardouin & Gattey, Paris, 1787, pp. 574–580

- ^ Although up to four feet in each dimension could still qualify; see the Metropolitan Rubens.

- ^ Rubens from Metropolitan New York

- ^ Metropolitan Timeline of Art History

- ^ Strong, Roy: Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered 1520-1620, Victoria & Albert Museum exhibit catalogue, 1983, pp. 156-67, ISBN 0-905209-34-6