CSS New Orleans

New Orleans, as portrayed by the Union The Philadelphia Inquirer on April 11, 1862[1] | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | New Orleans |

| Commissioned | October 14, 1861 |

| Fate | Scuttled, April 8, 1862 |

| Notes | Captured by Union forces and used as a floating drydock. Burned by the Confederates in August or September 1863 |

| General characteristics (as designed) | |

| Type | Floating battery |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | Iron sheathing |

CSS New Orleans was a floating battery used by the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Converted from a floating drydock in 1861, she was commissioned on October 14, 1861. The vessel was unable to move under her own power and lacked facilities for her crew to live aboard, so CSS Red Rover was used to move the floating battery and house her crew. She was then sent upriver to assist in the Confederate defense of Columbus, Kentucky, arriving there in December. After the Confederates abandoned Columbus in March 1862, New Orleans was moved to Island No. 10 near New Madrid, Missouri. The Confederate defenders of Island No. 10 surrendered on April 8, and New Orleans was scuttled that day. Not fully sunk, the floating battery drifted downriver to the New Madrid area, where it was captured by Union forces. In Union hands, New Orleans was used as a floating drydock until the Confederates burned her in August or September 1863.

Construction and characteristics

In early 1861, the secessionist Confederate States of America proclaimed its independence, although the United States government did not recognize the secession. The Confederates lacked a navy and had to build one from scratch. New Orleans, Louisiana was one of the premier ports of the Confederate states, and the city was one of the points of focus for the Confederates when building their navy.[2] Control of the Mississippi River was considered to be an important facet of the American Civil War by both sides.[3] In September 1861, Confederate troops commanded by Leonidas Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky, violating the state's official neutrality.[4] Columbus became the northernmost major Confederate defensive point on the Mississippi River.[5] The Confederates initiated a shipbuilding effort at New Orleans, part of which were two floating batteries – CSS New Orleans and CSS Memphis.[6]

Both floating batteries were converted from existing floating drydocks. The one used for New Orleans cost the Confederacy $50,000,[1] was known as the Pelican Drydock[7] and had been based at Algiers, Louisiana.[8] The conversion process of New Orleans alone consumed 70,000 feet (21,000 m) of pine boards, and 16 tons of iron sheathing. She had a casemate for protection of the guns and crew that consisted of a slanted wooden frame armored with iron. The naval historian Donald L. Canney states that the vessel's dimensions are unknown,[9] but historians Larry J. Daniel and Lynn N. Bock state that she measured 60 feet (18 m) by 180 feet (55 m).[10] Through the use of a pump, the draft of New Orleans could be raised and lowered as needed, including far enough so that the portion protected by iron sheathing was low enough to be the waterline.[10] Her designed armament was 20 cannons:[11] seventeen 8-inch (20 cm) pieces, two 32-pounder guns, and a 9-inch (23 cm) Dahlgren gun.[7] The 32-pounder guns were rifled artillery.[11] Additional self-defense was provided by a setup of boilers and pumps that allowed New Orleans' crew to use hoses to squirt boiling water at any potential boarding parties. The setup also provided for intentional flooding of the ship's magazine if necessary.[1] New Orleans was incapable of moving under her own power, and lacked living quarters for her crew, so the sidewheel steamer CSS Red Rover was used to tow the floating battery around and house her crew. The two vessels shared most of their crew.[11]

Service history

New Orleans was commissioned on October 14, 1861, commanded by Lieutenant Samuel W. Averett.[12] First Lieutenant John J. Guthrie commanded Red Rover.[11] On November 20, New Orleans was sent up the Mississippi River from New Orleans, towed by CSS Ivy. Red Rover left New Orleans five days later, and later met Ivy at Columbia, Arkansas, where it took over the process of towing New Orleans. The floating battery reached Columbus on December 11.[13] The total crew of the floating battery numbered nine officers and about 25 enlisted men at the time that it left New Orleans.[14] At this time, it was armed with six 8-inch columbiads;[10] this differed from the designed armament of 20 guns.[11] On January 7, 1862, New Orleans prepared for action upon the approach of Union Navy warships, but the Union vessels withdrew after sighting the floating battery.[15] Four days later, Red Rover towed New Orleans to accompany three other Confederate vessels in an operation that became the Battle of Lucas Bend. Red Rover came under Union fire, and returned to Columbus, still towing New Orleans.[16]

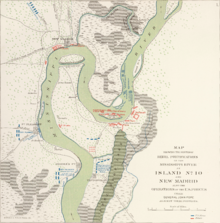

The Confederates abandoned Columbus on March 2 after Union victories at the battle of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, withdrawing to New Madrid, Missouri, and the fortified position of Island No. 10.[17] Three 8-inch Columbiads were taken from New Orleans for use in the land batteries at Island No. 10.[18] March 7 saw a cannon on the gunboat CSS McRae burst, and one of the floating battery guns was taken to replace it.[19] On March 13, New Orleans was reported to have been armed with a single 32-pounder rifled cannon and eight 8-inch columbiads.[20] At Island No. 10, the vessel was positioned in a location near the island where it could fire on the north river channel that went past.[21] New Madrid was captured by Union troops on March 14, leaving the Confederates at Island No. 10 with only a tenuous supply route through a swamp to Tiptonville, Tennessee.[22] The same day, the 1st Alabama Infantry Regiment arrived at Island No. 10, and a company of the regiment was assigned to the floating battery to help serve the artillery.[23] Union artillery fired on New Orleans on the night of March 17/18, although the Confederates claimed New Orleans silenced the guns with return fire.[24]

April 2 saw the floating battery moved to another position where it could fire on Union shore batteries. The Confederate fire was ineffective, and New Orleans was returned to her prior location. The Union Navy responded by bombarding the floating battery with three vessels, resulting in the floating battery suffering significant damage and one gun disabled. Its mooring cable was shot away, and the battery had to be retrieved by the transport Ohio Belle.[25] On the night of April 4/5, the Union ironclad USS Carondelet ran past the Confederate batteries at Island No. 10 downriver to New Madrid. New Orleans joined in with the Confederate shore defenses in firing at the ironclad, but the Union vessel did not suffer major damage.[26] The floating battery fired six or eight shots during the engagement.[27] Early on the morning of April 7, the ironclad USS Pittsburgh completed another run past the island, and the Confederate defenders of Island No. 10 began evacuating on the night of April 7/8. Their retreat was blocked by Union Navy vessels early on the morning of April 8, and they surrendered. When Union forces approached the floating battery and the small force left behind at the island, New Orleans was scuttled by her crew by opening valves that allowed water in.[28] This resulted in the battery becoming partially submerged.[29] The abandoned New Orleans then floated downstream, where it was fired on by Union batteries at New Madrid. It ran aground on the Missouri bank of the river.[30] When Union troops examined her, they found five 8-inch Columbiads and a 32-pounder rifled gun aboard.[31] She was captured by Union forces and again used as a floating drydock; she was burned by Confederate forces in August or September 1863.[32]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Chatelain 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, pp. 7–10.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 39.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Hearn 1995, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Canney 2015, p. 176.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Canney 2015, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b c Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Chatelain 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 75.

- ^ Dufour 1994, p. 106.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 93.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 98.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 109.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 108.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 110.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 115.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 126.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 136.

- ^ Daniel & Bock 1996, p. 138.

- ^ Canney 2015, p. 177.

- ^ Gaines 2008, pp. 100–101.

Sources

- Canney, Donald L. (2015). The Confederate Steam Navy 1861–1865. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-4824-2.

- Chatelain, Neil P. (2020). Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-510-6.

- Daniel, Larry J.; Bock, Lynn N. (1996). Island No. 10: Struggle for the Mississippi Valley. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0816-4.

- Dufour, Charles L. (1994) [1960]. The Night the War Was Lost. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6599-9.

- Gaines, W. Craig (2008). Encyclopedia of Civil War Shipwrecks. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3274-6.

- Hearn, Chester G. (1995). The Capture of New Orleans 1862. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1945-8.