Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency

| Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acquired angioedema |

| |

| Angioedema (or swelling) of the face and upper lip | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Swelling |

| Complications | Airway obstruction, anaphylaxis |

| Usual onset | 4th decade of life and older |

| Duration | Episodic, typically lasting 2-4 days |

| Types | AAE-I, AAE-II, medication-induced AAE, estrogen-dependent AAE |

| Causes | Lymphatic malignancies, MGUS, autoimmune disorders |

| Diagnostic method | Medical examination, complement studies |

| Differential diagnosis | Hereditary angioedema, allergic reaction |

| Treatment | C1-INH concentrate |

| Prognosis | Dependent on resolution of underlying disorder |

| Frequency | 1:10,000 - 1:150,000 |

Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency, also referred to as acquired angioedema (AAE), is a rare medical condition that presents as body swelling that can be life-threatening and manifests due to another underlying medical condition.[1]: 153 The acquired form of this disease can occur from a deficiency or abnormal function of the enzyme C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH). This disease is also abbreviated in medical literature as C1INH-AAE. This form of angioedema is considered acquired due to its association with lymphatic malignancies, immune system disorders, or infections. Typically, acquired angioedema presents later in adulthood, in contrast to hereditary angioedema which usually presents from early childhood and with similar symptoms.[2]

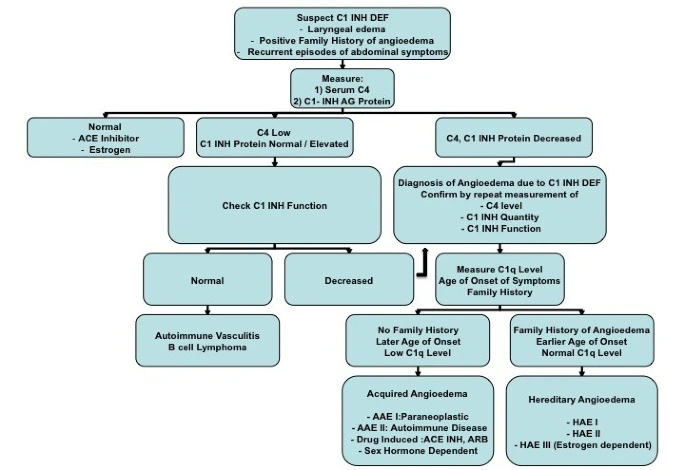

Acquired angioedema is usually found after recurrent episodes of swelling and can in some cases take several months to diagnose. Diagnosis usually consists of medical evaluation in addition to laboratory testing. Laboratory evaluation includes complement studies, in which typical cases demonstrate low C4 levels, low C1q levels, and normal C3 levels.[3] Determining the etiology, or cause, of acquired angioedema is often helpful in providing appropriate management of AAE.

Management of AAE usually includes treating any underlying disorder that could be responsible for the condition. Additionally, symptom management is important, especially in cases that are life-threatening. There are medications available to treat AAE, which are focused on replacing deficient levels of C1-INH or abnormal C1-INH enzymes. There are some cases of partial improvement and full resolution with treatment of the underlying medical problems contributing to AAE.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that the worldwide prevalence of AAE ranges from 1 person in every 10,000 people are affected to 1 case in every 150,000 people.[4] However, it is thought that this disease prevalence could be higher due to diagnostic oversight and the shared symptoms of acquired angioedema with similar diseases.[5] This disease tends to affect males and females equally.[4] Additionally, individuals with acquired angioedema usually develop symptoms in their fourth decade of life or older.[4] Of note, Saini reports the difficulty of diagnosing angioedema accurately due to certain challenges.[2] These obstacles include the lack of awareness about angioedema presentation and potentially higher than expected worldwide prevalence.[2] More challenges include the similarities to paraneoplastic disorders that often require higher priority of care, the evolution of symptoms over time, and mild cases might be attributed to medication use or allergic reactions from an individual's existing medical history.[2] As a result, accurate diagnosis of AAE can take several months, which can delay targeted and specific treatment.[2]

Causes

There are various disease comorbidities associated with acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency, including:[6]

Lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphatic malignancies

- Lymphoproliferative disorders, such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma are associated with acquired angioedema. In cohort studies, MGUS is considered one of the most common disorders associated with AAE.[7] MGUS is a premalignant plasma cell disorder that is associated with bone marrow pathologic changes leading to abnormal production of M protein that can progress to other hematologic diseases.[8] Additionally, through retrospective case studies performed in France, Gobert et al. found that non-Hodgkin lymphoma was associated with 48% of cases in a sample size of 92 cases of acquired angioedema.[7]

- Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disorder that progresses from MGUS. MM is characterized by elevated monoclonal paraprotein in addition to end organ damage, such as kidney failure.[9]

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (also known as Waldenström macroglobulinemia) is a B cell malignancy with hematologic changes that affect the lymphatic system.[10] Some of the clinical manifestations seen in this lymphoma are anemia, hyperviscosity syndrome, and neuropathy.[10]

Autoimmune disorders

- Autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are observed with AAE. SLE is an autoimmune disease with variable manifestations from mild symptoms to multiorgan involvement.[11] The autoantibody component involved in SLE has been investigated and is thought to be associated with angioedema manifestations.[11]

- Certain vasculitic diseases, such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) have been associated with AAE.[citation needed] EGPA is an inflammatory disease characterized by necrotizing vasculitis that affects small and medium-sized vessels of the body.[12] This vasculitis is associated with certain comorbidities including asthma, rhinosinusitis, and eosinophilia (blood cells responsible for activating immune responses and downstream signals in inflammation).[12]

Infections

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a transmissible retrovirus that can predispose individuals carrying the virus to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which leads to opportunistic infections.[13]

- Hepatitis B viral infection (HBV) is a transmissible DNA virus that can potentially lead to liver injury.[14] In a series of cases studies with patients reporting symptoms of angioedema, some of these individuals were found to have positive markers of HBV.[15]

Metabolic disorders

- Xanthomatosis is a systemic metabolic disorder marked by fatty deposits in the presence of hypercholesterolemia, or high cholesterol.[16]

Idiopathic causes

- Idiopathic etiology is considered when well-understood and known causes are excluded after a thorough medical evaluation.[4]

Pathophysiology

The C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) enzyme plays a role in the classical pathway of the complement cascade, which is a component of the immune system response that acts to protect the human body from a variety of foreign substances.[5] As shown in the figure above, the complement cascade starts with the C1q protein which binds to an antibody-antigen complex that arises during an immune response to an invading substance.[5] When the complex is signaled for activation or turned on, then downstream proteins in the complement cascade are activated, including complement component 2 (C2), complement component 3 (C3), and complement component 4 (C4).[5] When these particular enzymes such as C3 and C4 are activated, their subsequent signals lead to an inflammatory response that involves localized edema, or swelling.[4] The role of C1-INH is to regulate and control the activities of the complement cascade, such that complement proteins remain in check and do not lead to unnecessary activity.[4] When there is a deficiency of C1-INH due to one of the previously mentioned causes, then the complement cascade remains continuously activated and can lead to potentially life-threatening swelling.[4]

Clinical Presentation

Acquired angioedema presents as mucosal swelling on external and/or internal surfaces of the body. Typical areas of swelling include the face, arms, and legs, while internally some individuals have swelling of the tongue and upper airways.[3] In contrast to hereditary angioedema, there tend to be fewer symptoms of the abdomen or gastrointestinal tract, but symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea have been seen in acquired angioedema.[3] Although this condition appears similar to other skin conditions in which swelling occurs, acquired angioedema does not lead to itchy skin (pruritus) or hives (urticaria).[2]

Diagnosis

Acquired angioedema is diagnosed through a supportive clinical examination usually in addition to laboratory evaluation.[2] The clinical history consists of recurrent angioedema episodes, symptom onset after 30 years of age, and negative family history of hereditary angioedema.[2]

Laboratory evaluation typically consists of complement studies, genotyping, and/or checking for antibodies against C1INH.[2] The most useful complement studies obtained are as follows:[2]

- C4 level

- C3 level

- C1 INH antigenic level

- C1 INH function

- C1q level

To help confirm cases of acquired angioedema, the following pattern of complement studies are observed: low C4 level, low C1-INH protein level, low C1q level, and decreased C1-INH protein function.[17][18]

Using the diagnostic approach mentioned here and in the figure shown above, acquired angioedema is categorized into subtypes for targeted management. The following subtypes include AAE-I, AAE-II, sex-hormone dependent AAE, and drug-induced AAE.[18] AAE-I subtype groups paraneoplastic syndrome or B-cell malignancies that lead to the destruction of the C1-INH enzyme causing acquired angioedema.[18] AAE-II subtype groups autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus, causing acquired angioedema.[18] Sex-hormone dependent AAE is associated with case reports of individuals with abnormally elevated estrogen levels or in cases where physiologically elevated estrogen is expected as in pregnancy.[18] Drug-induced AAE can be triggered by certain medications, including ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.[18]

Furthermore, additional laboratory testing can be done to consider other causes of swelling that appear similar to angioedema.[2] Some of the common differential diagnoses for angioedema include: allergic reactions, contact dermatitis, skin and soft tissue infections (i.e. cellulitis), lymphedema, and foreign body aspiration.[19]

Management

Treatment of acquired angioedema is separated into two main parts. First controlling acute symptoms during angioedema attacks is crucial for preventing and lowering the risk of mortality.[20] Second, managing AAE chronically with prophylactic treatment is important to improve prognosis and quality of life.[20] Both pharmacologic therapies (i.e. medications) and symptom management can be used in both acute and chronic treatment of AAE.[20]

Pharmacologic treatment in acute situations consists of replacing the enzyme concentrate that is deficient or dysfunctional in this disease process.[20] In life-threatening situations, including cases of oral and pharyngeal swelling, it is important to manage these symptoms and to protect the airways to lower the risk of mortality.[20] Typical treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic reactions, such as epinephrine, corticosteroids, and antihistamines, are often used in acute cases of AAE with variable resolution.[4] C1-INH concentrates are available in intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) methods of delivery.[4] C1-INH concentrate therapy has shown considerable efficacy (or effect) in acute and prophylactic treatments of hereditary angioedema but has varying levels of efficacy in AAE.[4]

For prophylaxis, clinicians focus on controlling underlying disorders, such as those mentioned under causes, that could be contributing to AAE pathophysiology.[20] Beyond controlling comorbidities, angioedema is usually managed through medications to prevent attacks and to reduce the number of attacks.[6] C1-INH concentrate can be used to replace deficient or abnormal C1-INH enzyme with considerable efficacy.[6] The following list of medical therapies have been used for prophylaxis, including androgens, tranexamic acid, and monoclonal antibody such as rituximab.[6] These agents all have varying roles, efficacy, and potential risks through their use.[6]

Prognosis

The evaluation of acquired angioedema usually prompts an investigation into the underlying cause.[6] As mentioned in the causes section, malignancy or autoimmune disorders are the more common causes, which must be further explored and considered for treatment if found in an individual.[6] Prognosis depends on the underlying disorder, which may be found at the time of initial diagnosis or through ongoing monitoring.[6] Additionally, successful treatment of the underlying disorder has been observed in some cases to resolve acquired angioedema from partial to complete remission.[6]

See also

References

- ^ James W, Berger T, Elston D (2005). 'Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0..

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Saini S (13 February 2020). Bochner BS, Feldweg AM (eds.). "Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency: Clinical manifestations, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis". UpToDate. Retrieved 2021-11-06.

- ^ a b c Markovic SN, Inwards DJ, Frigas EA, Phyliky RP (January 2000). "Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency". Annals of Internal Medicine. 132 (2): 144–150. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-2-200001180-00009. PMID 10644276. S2CID 33965547.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nzeako UC, Frigas E, Tremaine WJ (November 2001). "Hereditary angioedema: A broad review for clinicians". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (20): 2417–2429. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.20.2417. PMID 11700154.

- ^ a b c d Cicardi M, Johnston DT (2012). "Hereditary and acquired complement component 1 esterase inhibitor deficiency: A review for the hematologist". Acta Haematologica. 127 (4): 208–220. doi:10.1159/000336590. PMID 22456031. S2CID 1817978.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Otani IM, Banerji A (August 2017). "Acquired C1 Inhibitor Deficiency". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 37 (3): 497–511. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2017.03.002. PMID 28687105.

- ^ a b Gobert D, Paule R, Ponard D, Levy P, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Bouillet L, et al. (August 2016). "A nationwide study of acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency in France: Characteristics and treatment responses in 92 patients". Medicine. 95 (33): e4363. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004363. PMC 5370791. PMID 27537564.

- ^ Kaseb, H; Annamaraju, P; Babiker, HM (2021), "Monoclonal Gammopathy Of Undetermined Significance", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29939657, retrieved 2021-11-13

- ^ Albagoush, SA; Azevedo, AM (2021), "Multiple Myeloma", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30521185, retrieved 2021-11-14

- ^ a b Kaseb, H; Gonzalez-Mosquera, LF; Parsi, M; Mewawalla, P (2021), "Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020728, retrieved 2021-11-14

- ^ a b Justiz Vaillant, AA; Goyal, A; Bansal, P; Varacallo, M (2021), "Systemic Lupus Erythematosus", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30571026, retrieved 2021-11-13

- ^ a b Chakraborty, RK; Aeddula, NR (2021), "Churg Strauss Syndrome", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725784, retrieved 2021-11-14

- ^ Justiz Vaillant, AA; Gulick, PG (2021), "HIV Disease Current Practice", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30521281, retrieved 2021-11-13

- ^ Tripathi, N; Mousa, OY (2021), "Hepatitis B", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32310405, retrieved 2021-11-14

- ^ Vaida, G; Goldman, M; Bloch, K (August 1983). "Testing for hepatitis B virus in patients with chronic urticaria and angioedema". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 72 (2): 193–198. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(83)90529-8. PMID 6886256.

- ^ Bell, A; Shreenath, AP (2021), "Xanthoma", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965912, retrieved 2021-11-14

- ^ "Hereditary and Acquired Angioedema - Immunology; Allergic Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kothari ST, Shah AM, Botu D, Spira R, Greenblatt R, Depasquale J (February 2011). "Isolated angioedema of the bowel due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency: a case report and review of literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 5 (1): 62. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-62. PMC 3089795. PMID 21320328.

- ^ Zuraw, B (October 2021). "An overview of angioedema: Clinical features, diagnosis, and management". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 2021-11-11. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f Saini S (13 February 2020). Bochner BS, Feldweg AM (eds.). "Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency: Management and prognosis". UpToDate. Retrieved 2021-11-06.