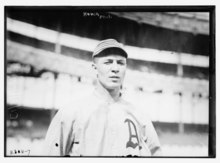

Byron Houck

| Byron Houck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: Byron Simon Houck August 28, 1891 Prosper, Minnesota | |

| Died: June 17, 1969 (aged 77) Santa Cruz, California | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| May 15, 1912, for the Philadelphia Athletics | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 27, 1918, for the St. Louis Browns | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 26–24 |

| Earned run average | 3.30 |

| Strikeouts | 224 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| |

Byron Simon Houck (August 28, 1891 – June 17, 1969) was an American professional baseball pitcher and cinematographer. He played in Major League Baseball for the Philadelphia Athletics, Brooklyn Tip-Tops, and St. Louis Browns from 1912 to 1914 and in 1918. After his baseball career, he worked on Buster Keaton's production team as a camera operator.

Early life

Houck was born in Prosper, Minnesota. He was the fifth of six children. His family moved to Portland, Oregon, when he was young.[1] He attended Washington High School in Portland, and pitched for the school's baseball team all four years.[2] In his senior year, he was voted president of the athletic association.[3] Houck graduated from high school in 1910 and enrolled at the University of Oregon and played college baseball for the Oregon Ducks. He was a member of Kappa Sigma at Oregon.[4]

Professional baseball career

Houck signed with the Spokane Indians of the Class B Northwestern League in July 1911.[5] After the season, the Philadelphia Athletics selected Houck in the Rule 5 draft.[6] He made his major league debut with the Athletics in 1912.[7] He pitched to a 8–8 win–loss record with a 2.94 earned run average (ERA).[8] He was a member of the 1913 World Series champions, pitching to a 14–6 record and a 4.14 ERA in 1913,[9] but he did not appear in the series. In 1914, after making three appearances for the Athletics,[10] he was released to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League. Houck refused to report to Baltimore, and jumped to the Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the outlaw Federal League.[11] He signed a three-year contract with Brooklyn[12] paying him $3,500 per season ($106,465 in current dollar terms).[1] He pitched to a 2–6 record with a 3.13 ERA for Brooklyn.[13] In 1915, Brooklyn assigned him to the Colonial League, a minor league affiliated with the Federal League, and he played for the New Haven White Wings and Pawtucket Rovers.[1] Brooklyn gave him his unconditional release after the 1915 season, and Houck accepted a payout of half of his salary for the 1916 season.[12][14]

In 1916, following the collapse of the Federal League, Houck's rights reverted to the Athletics,[1][15] and they allowed Houck to become a free agent.[1] He signed with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League (PCL).[16] He had a 17–19 record and a 3.36 ERA in 1916.[17] Houck returned to Portland in 1917, but struggled at the beginning of the season.[18] He improved to finish the season with a 23–15 record and a 2.21 ERA.[19] After the 1917 season, he was drafted by the St. Louis Browns for the 1918 season.[20] He had a 2–4 record and a 2.39 ERA for the Browns.[21] In February 1919, St. Louis sold Houck to the Vernon Tigers of the PCL.[22] He had a 19–16 record and a 3.88 ERA in 1919.[23] In 1920, Babe Borton, Houck's teammate with Vernon, was caught bribing opponents to throw games. He alleged that the plan was discussed at Louis Anger's house with Houck present.[24] Houck was not punished by the PCL.[1] He finished the 1920 season with a 10–17 record and a 2.62 ERA.[25] Houck played semi-professional baseball in 1921, and briefly returned to the PCL to pitch for Vernon and Portland in 1922.[1][26][27]

Film career

In 1919, Fatty Arbuckle purchased the Tigers, and he made Anger the team president. Houck's first wife and Anger's wife were sisters. This connection led to Houck working as a camera operator on Buster Keaton's silent films.[1] He worked on the 1924 films Sherlock Jr.[28] and The Navigator,[29] the 1925 film Seven Chances,[30] and the 1926 film The General.[31]

Personal life

Houck married Kittye Isaacs in September 1913.[1][32] She died in March 1923.[33] He remarried to Rose Carr in 1927.[1]

Houck died in Santa Cruz, California, on June 17, 1969.[34] He was interred at Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles.[35]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Williams, Phil. "Byron Houck". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "28 Jul 1912, Page 41". The Oregon Daily Journal. July 28, 1912. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "16 Jan 1910, Page 57". The Oregon Daily Journal. January 16, 1910. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "4 Oct 1911, 17". The Spokesman-Review. October 4, 1911. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "26 Jul 1911, Page 11". The Oregon Daily Journal. July 26, 1911. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "3 Sep 1911, Page 35". The Oregon Daily Journal. September 3, 1911. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "9 Apr 1912, Page 6". The Eugene Guard. April 9, 1912. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1912 Philadelphia Athletics Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "1913 Philadelphia Athletics Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "1914 Philadelphia Athletics Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "21 May 1914, 2". The Boston Globe. May 21, 1914. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "30 Sep 1915, Page 20". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 30, 1915. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1914 Brooklyn Tip-Tops Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "8 Nov 1915, Page 9". The Wilkes-Barre Record. November 8, 1915. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "20 Jan 1916, 4". Times Union. January 20, 1916. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "5 Mar 1916, Page 15". The Washington Herald. March 5, 1916. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1916 Portland Beavers Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "15 May 1917, Page 10". The Oregon Daily Journal. May 15, 1917. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1917 Portland Beavers Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "5 Nov 1917, 8". The La Crosse Tribune. November 5, 1917. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1918 St. Louis Browns Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "3 Feb 1919, Page 10". The Oregon Daily Journal. February 3, 1919. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1919 Vernon Tigers Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "19 Oct 1920, 12". The Salt Lake Tribune. October 19, 1920. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1920 Vernon Tigers Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "12 Jul 1922, Page 4 – Santa Cruz Evening News". July 12, 1922. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Byron Houck To Swing Arm For Beavers". Newspapers.com. July 15, 1922. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "2 Jun 1924, 20". Calgary Herald. June 2, 1924. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "23 Dec 1925, 1". Mauch Chunk Times-News. December 23, 1925. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "9 May 1925, Page 21". The Evening News. May 9, 1925. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "30 Aug 1926, Page 8". The Eugene Guard. August 30, 1926. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "16 Sep 1913, Page 3". The Eugene Guard. September 16, 1913. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Byron Houck's Wife Dead; Ill Long Time". Los Angeles Evening Express. March 27, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "18 Jun 1969, Page 15". Santa Cruz Sentinel. June 18, 1969. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "25 Jun 1969, Page 14". Santa Cruz Sentinel. June 25, 1969. Retrieved March 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Byron Houck at IMDb

- Byron Houck at Find a Grave