Buddy Holly

Buddy Holly | |

|---|---|

Holly ca. 1957 | |

| Born | Charles Hardin Holley September 7, 1936 Lubbock, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | February 3, 1959 (aged 22) |

| Cause of death | Blunt trauma as a result of a plane accident |

| Resting place | City of Lubbock Cemetery in Lubbock County, Texas |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1952–1959 |

| Spouse | |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Buddy Holly discography |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

Charles Hardin Holley (September 7, 1936 – February 3, 1959), known as Buddy Holly, was an American singer, songwriter, and musician who was a central and pioneering figure of mid-1950s rock and roll. He was born to a musical family in Lubbock, Texas, during the Great Depression, and learned to play guitar and sing alongside his two siblings.

Holly made his first appearance on local television in 1952, and the following year he formed the group Buddy and Bob with his friend Bob Montgomery. In 1955, after opening once for Elvis Presley, Holly decided to pursue a career in music. He played with Presley three times that year, and his band's style shifted from country and western to rock and roll. In October that year, when Holly opened for Bill Haley & His Comets, he was spotted by Nashville scout Eddie Crandall, who helped him get a contract with Decca Records.

Holly's recording sessions at Decca were produced by Owen Bradley, who had become famous for producing orchestrated country hits for stars like Patsy Cline. Unhappy with Bradley's musical style and control in the studio, Holly went to producer Norman Petty in Clovis, New Mexico, and recorded a demo of "That'll Be the Day", among other songs. Petty became the band's manager and sent the demo to Brunswick Records, which released it as a single credited to the Crickets, a name chosen by the band to subvert Decca's contract limitations. In September 1957, as the band toured, "That'll Be the Day" topped the US and UK singles charts. Its success was followed in October by another major hit, "Peggy Sue".

The album The "Chirping" Crickets, released in November 1957, reached number five on the UK Albums Chart. Holly made his second appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in January 1958 and soon after toured Australia and then the UK. In early 1959, he assembled a new band, consisting of Waylon Jennings (bass), Tommy Allsup (guitar), and Carl Bunch (drums), and embarked on a tour of the mid-western US. After a show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly chartered an airplane to travel to his next show in Moorhead, Minnesota. Soon after takeoff, the plane crashed, killing Holly, Ritchie Valens, the Big Bopper, and pilot Roger Peterson in a crash later referred to by Don McLean as "The Day the Music Died" in his song "American Pie".

During his short career, Holly wrote and recorded many songs. He is often regarded as the artist who defined the traditional rock-and-roll lineup of two guitars, bass, and drums. Holly was a major influence on later popular music artists, including Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, the Hollies, Elvis Costello and Elton John. Holly was among the first artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in 1986. Rolling Stone magazine ranked him number 13 in its list of 100 Greatest Artists in 2010.

Life and career

Early life and career (1936–1955)

Charles Hardin Holley (spelled "-ey") was born in Lubbock, Texas, on September 7, 1936, the youngest of four children of Lawrence Odell "L.O." Holley (1901–1985) and Ella Pauline Drake (1902–1990). His elder siblings were Larry (1925–2022),[1] Travis (1927–2016),[2] and Patricia Lou (1929–2008).[3] Holly was of mostly English and Welsh descent and had small amounts of Native American ancestry as well.[4] From early childhood, Holly was nicknamed "Buddy."[5] During the Great Depression, the Holleys frequently moved residence within Lubbock; L.O. changed jobs several times. Buddy Holly was baptized a Baptist, and the family were members of the Tabernacle Baptist Church.[5]

The Holleys had an interest in music; all the family members except L.O. were able to play an instrument or sing. The elder Holley brothers performed in local talent shows; on one occasion, Buddy joined them on violin. Since he could not play it, his brother Larry greased the bow so it would not make any sound. The brothers won the contest.[6] During World War II, Larry and Travis were called to military service. Upon his return, Larry brought with him a guitar he had bought from a shipmate while serving in the Pacific. At age 11, at his mother's urging, Buddy took piano lessons but abandoned them after nine months. He switched to the guitar after he saw a classmate playing and singing on the school bus. Buddy's parents initially bought him a steel guitar, but he insisted that he wanted a guitar like his brother's. His parents bought him an acoustic guitar from a local pawnshop, and he learned how to play it from Travis.[7]

During his early childhood, Holly was influenced by the music of Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Moon Mullican, Bill Monroe, Hank Snow, Bob Wills, and the Carter Family. At Roscoe Wilson Elementary, Holly became friends with Bob Montgomery, and the two played together, practicing with songs by The Louvin Brothers and Johnnie & Jack.[8] They both listened to the radio programs Grand Ole Opry on WSM, Louisiana Hayride on KWKH, and Big D Jamboree. At the same time, Holly played with other musicians he met in high school, including Sonny Curtis and Jerry Allison.[9] In 1952 Holly and Jack Neal participated as a duo billed as Buddy and Jack in a talent contest on a local television show. After Neal left, he was replaced by Bob Montgomery, and they were billed as Buddy and Bob. They soon started performing on the Sunday Party show on KDAV in 1953 and performed live gigs in Lubbock.[10] At that time, Holly was influenced by late-night radio stations that played blues and rhythm and blues (R&B). He would sit in his car with Curtis and tune to distant radio stations that could only be received at night, when local transmissions ceased.[11] Holly then modified his music by blending his earlier country and western influence with R&B.[12]

By 1955, after graduating from Lubbock High School, Holly decided to pursue a full-time career in music. He was further encouraged after seeing Elvis Presley perform live in Lubbock, whose act was booked by Pappy Dave Stone of KDAV. In February, Holly opened for Presley at the Fair Park Coliseum, in April at the Cotton Club, and again in June at the Coliseum. By that time, Holly had incorporated into his band Larry Welborn on the stand-up bass and Allison on drums, as his style shifted from country and western to rock and roll due to seeing Presley's performances and hearing his music.[11] In October, Stone booked Bill Haley & His Comets and placed Holley as the opening act to be seen by Nashville scout Eddie Crandall. Impressed, Crandall persuaded Grand Ole Opry manager Jim Denny to seek a recording contract for Holley. Stone sent a demo tape, which Denny forwarded to Paul Cohen, who signed the band to Decca Records in February 1956.[13] In the contract, Decca misspelled Holly's surname as "Holly", and from then on he was known as Buddy Holly, instead of his real name Holley.[citation needed]

On January 26, 1956, Holly attended his first formal recording session, which was produced by Owen Bradley.[14] He attended two more sessions in Nashville, but with the producer selecting the session musicians and arrangements, Holly became increasingly frustrated by his lack of creative control.[13] In April 1956, Decca released "Blue Days, Black Nights" as a single, with "Love Me" on the B-side. Denny included Holly on a tour as the opening act for Faron Young. During the tour, they were promoted as Buddy Holly and the Two Tones, while later Decca called them Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes.[13] The label later released Holly's second single "Modern Don Juan", backed with "You Are My One Desire". Neither single made an impression. On January 22, 1957, Decca informed Holly his contract would not be renewed, but insisted he could not record the same songs for anyone else for five years.[15]

The Crickets (1956–1957)

Holly was unhappy with the results of his time with Decca, and inspired by the success of Buddy Knox's "Party Doll" and Jimmy Bowen's "I'm Stickin' with You", he visited Norman Petty, who had produced and promoted both records. Together with Allison, bassist Joe B. Mauldin, and rhythm guitarist Niki Sullivan, he went to Petty's studio in Clovis, New Mexico. The group recorded a demo of "That'll Be the Day", a song they had previously recorded in Nashville. In June 1956, Holly along with his older brother Larry as well as Allison and Sonny Curtis had gone to see the film The Searchers, starring John Wayne, in which Wayne repeatedly used the phrase "That'll be the day". This line of dialogue inspired the young musicians.[16][17] Now playing lead guitar, Holly achieved the sound he desired. Petty became his manager and sent the record to Brunswick Records in New York City. Holly, still under contract with Decca, could not release the record under his name, so a band name was used; Allison proposed the name "Crickets." Brunswick gave Holly a basic agreement to release "That'll Be the Day", leaving him with both artistic control and financial responsibility for future recordings.[18]

Impressed with the demo, the label's executives released it without recording a new version. "I'm Looking for Someone to Love" was the B-side; the single was credited to The Crickets. Petty and Holly later learned that Brunswick was a subsidiary of Decca, which legally cleared future recordings under the name Buddy Holly. Recordings credited to the Crickets would be released on Brunswick, while the recordings under Holly's name were released on another subsidiary label, Coral Records. Holly concurrently held a recording contract with both labels.[19]

Norman Petty reasoned correctly that disc jockeys would be reluctant to play and promote multiple new records by the same artist, but would have no problem playing these same records if they were credited to different performers. Holly himself was unaware of this strategy; in a 1957 radio interview with Dale Lowery, Holly said, "We have three records going out right now. Of course, the first one was 'That'll Be the Day', the first one released. Then we have a new one out by The Crickets, called 'Oh Boy!' and 'Not Fade Away', and then there's one out, it's the same group but it's under my name -- I don't know why they did it that way, but it went out under my name -- called 'Peggy Sue' and 'Everyday'."[20] Holly's records were released with labels reading "Buddy Holly" or "The Crickets"; the band was never credited on records as "Buddy Holly and the Crickets" until 1962, when a compilation album was released.

"That'll Be the Day" was released on July 27, 1957. Petty booked Holly and the Crickets for a tour with Irvin Feld, who had noticed the band after "That'll Be the Day" appeared on the R&B chart. He booked them for appearances in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and New York City.[21] The band was booked to play at New York's Apollo Theater on August 16–22. During the opening performances, the group did not impress the audience, but they were accepted after they included "Bo Diddley." By the end of their run at the Apollo, "That'll Be the Day" was climbing the charts. Encouraged by the single's success, Petty started to prepare two album releases; a solo album for Holly and another for the Crickets.[22] Holly appeared on American Bandstand, hosted by Dick Clark on ABC, on August 26. Before leaving New York, the band befriended The Everly Brothers.[23]

"That'll Be the Day" topped the US "Best Sellers in Stores" chart on September 23 and was number one on the UK Singles Chart for three weeks in November.[24] Three days prior, Coral released "Peggy Sue", backed with "Everyday", with Holly credited as the performer. By October, "Peggy Sue" had reached number three on Billboard's pop chart and number two on the R&B chart; it peaked at number six on the UK Singles chart. As the success of the song grew, it brought more attention to Holly, with the band at the time being billed as "Buddy Holly and the Crickets"[25] (although never on records during Holly's lifetime).

In the last week of September, the band members flew to Lubbock to visit their families.[26] Holly's high school girlfriend, Echo McGuire, had left him for a fellow student.[27] Aside from McGuire, Holly had a relationship with Lubbock fan June Clark.[28] After Clark ended their relationship, Holly realized the importance of his relationship with McGuire and considered his relationship with Clark a temporary one.[27] Meanwhile, for their return to recording, Petty arranged a session in Oklahoma City, where he was performing with his own band. While the band drove to the location, the producer set up a makeshift studio. The rest of the songs needed for an album and singles were recorded; Petty later dubbed the material in Clovis.[26] The resulting album, The "Chirping" Crickets, was released on November 27, 1957. It reached number five on the UK Albums Chart. In October, Brunswick released the second single by the Crickets, "Oh, Boy!", with "Not Fade Away" on the B-side. The single reached number 10 on the pop chart and 13 on the R&B chart.[25] Holly and the Crickets performed "That'll Be the Day" and "Peggy Sue" on The Ed Sullivan Show on December 1, 1957. Following the appearance, Niki Sullivan left the group because he was tired of the intensive touring, and wished to resume his education. On December 29, Holly and the Crickets performed "Peggy Sue" on The Arthur Murray Party.[29]

International tours and split (1958)

On January 8, 1958, Holly and the Crickets joined America's Greatest Teenage Recording Stars tour.[30] On January 25, Holly recorded "Rave On"; the next day, he made his second appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, singing "Oh, Boy!"[30] Holly departed to perform in Honolulu, Hawaii, on January 27, and then started a week-long tour of Australia billed as the Big Show with Paul Anka, Jerry Lee Lewis and Jodie Sands.[31][32] In March, the band toured the United Kingdom, playing 50 shows in 25 days.[33] The same month, his debut solo album, Buddy Holly, was released. Upon their return to the United States, Holly and the Crickets joined Alan Freed's Big Beat Show tour for 41 dates. In April, Decca released That'll Be the Day, featuring the songs recorded with Bradley during his early Nashville sessions.[34]

A new recording session in Clovis was arranged in May; Holly hired Tommy Allsup to play lead guitar. The session produced the recordings of "It's So Easy" and "Heartbeat." Holly was impressed by Allsup and invited him to join the Crickets. In June, Holly traveled alone to New York for a solo recording session. Without the Crickets, he chose to be backed by a jazz and R&B band, recording "Now We're One" and Bobby Darin's "Early in the Morning."[35]

During a visit to the offices of Peer-Southern, Holly met María Elena Santiago. He asked her out on their first meeting and proposed marriage to her on their first date. The wedding took place on August 15. Norman Petty had tried to dissuade Holly from marriage; he felt that it would disappoint Holly's public and damage his career.

Holly and Santiago frequented many of New York's music venues, including the Village Gate, Blue Note, Village Vanguard, and Johnny Johnson's. Santiago later said that Holly was keen to learn fingerstyle flamenco guitar and that he would often visit her aunt's home to play the piano there. Holly planned collaborations between soul singers and rock and roll. He wanted to make an album with Ray Charles and Mahalia Jackson. Holly also had ambitions to work in film and registered for acting classes with Lee Strasberg's Actors Studio.[36]

Santiago accompanied Holly on tours. To hide her marriage to Holly, she was presented as the Crickets' secretary. She took care of the laundry and equipment set-up and collected the concert revenues. Santiago kept the money for the band instead of its habitual transfer to Petty in New Mexico.[37] She and her aunt Provi Garcia, an executive in the Latin American music department at Peer-Southern, convinced Holly that Petty was paying the band's royalties from Coral-Brunswick into his own company's account. Holly planned to retrieve his royalties from Petty and to later fire him as manager and producer. At the recommendation of the Everly Brothers, Holly hired lawyer Harold Orenstein to negotiate his royalties.[38] The problems with Petty were triggered after he was unable to pay Holly. At the time, New York promoter Manny Greenfield reclaimed a large part of Holly's earnings; Greenfield had booked Holly for shows during previous tours. The two had a verbal agreement; Greenfield would obtain 5% of the booking earnings. Greenfield later felt he was also acting as Holly's manager and deserved a higher payment, which Holly refused. Greenfield then sued Holly. Under New York law, because Holly's royalties originated in New York and were directed out of the state, the payments were frozen until the dispute was settled.[39]

In September, Holly returned to Clovis for a new recording session, which yielded "Reminiscing" and "Come Back Baby." During the session, he ventured into producing by recording Lubbock DJ Waylon Jennings. Holly produced the single "Jole Blon" and "When Sin Stops (Love Begins)" for Jennings.[40] Holly became increasingly interested in the New York music, recording, and publishing scene. Holly and Santiago settled in Apartment 4H of the Brevoort Apartments, at 11 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village, where he recorded a series of acoustic songs, including "Crying, Waiting, Hoping" and "What to Do."[41] The inspiration to record the songs is sometimes attributed to the ending of his relationship with McGuire.[42]

On October 21, 1958, Holly's final studio session was recorded at the Pythian Temple on West 70th Street (now a luxury condominium). Known by Holly fans as "the string sessions", Holly recorded four songs for Coral in an innovative collaboration with an 18-piece ensemble composed of former members of the NBC Symphony Orchestra (including saxophonist Boomie Richman) under the direction of Dick Jacobs.

The four songs recorded during the 3+1⁄2-hour session were:

- "True Love Ways" (written by Buddy Holly),

- "Moondreams" (written by Norman Petty),

- "Raining in My Heart" (written by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant) and

- "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" (written by Paul Anka).[43]

These four songs were the only ones Coral ever mixed in stereo, but only "Raining in My Heart" was released that way (in 1959, on an obscure promotional LP titled Hitsville). All four records otherwise received releases in mono. The original stereo mixes were consulted many years later for compilation albums.

Holly ended his association with Petty in December 1958. His band members kept Petty as their manager and split from Holly. The split was amicable and based on logistics: Holly had decided to settle permanently in New York, where the business and publishing offices were, and the Crickets preferred not to leave their home state.

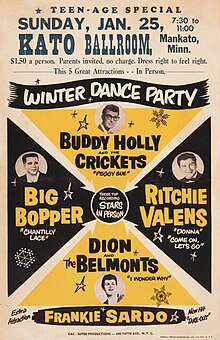

Winter Dance Party tour and death (1959)

Holly vacationed with his wife in Lubbock and visited Jennings's radio station in December 1958.[44] For the start of the Winter Dance Party tour, he assembled a band consisting of Waylon Jennings (electric bass), Tommy Allsup (guitar), and Carl Bunch (drums).[45] Holly and Jennings left for New York City, arriving on January 15, 1959. Jennings stayed at Holly's apartment by Washington Square Park on the days prior to a meeting scheduled at the headquarters of the General Artists Corporation, which organized the tour.[46] They then traveled by train to Chicago to join the rest of the band.[47]

The Winter Dance Party tour began in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on January 23, 1959. The amount of travel involved created logistical problems, as the distance between venues had not been considered when scheduling performances. Adding to the problem, the unheated tour buses twice broke down in freezing weather, with dire consequences. Holly's drummer, Carl Bunch, was hospitalized for frostbite to his toes (sustained while aboard the bus), so Holly decided to seek other transportation.[48] On February 2, before their appearance in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly chartered a four-seat Beechcraft Bonanza airplane for Jennings, Allsup, and himself, from Dwyer Flying Service in Mason City, Iowa. Holly's idea was to depart following the show at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake and fly to their next venue, in Moorhead, Minnesota, via Fargo, North Dakota, allowing them time to rest and launder their clothes and avoid an arduous bus journey. Immediately after the Clear Lake show (which ended just before midnight), Allsup agreed to flip a coin for the seat with Ritchie Valens. Valens called heads; when he won, he reportedly said, "That's the first time I've ever won anything in my life." Allsup later opened a restaurant/bar in Fort Worth, Texas, called Heads Up Saloon.[49] Waylon Jennings voluntarily gave up his seat to J. P. Richardson (the Big Bopper), who had influenza and complained that the tour bus was too cold and uncomfortable for a man of his size.[50]

The pilot, Roger Peterson, took off in inclement weather, even though he was not certified to fly by instruments only. Buddy's brother Larry Holley said, "I got the full report from the Civil Aeronautics – it took me a year to get it, but I got it – and they had installed a new Sperry gyroscope in the airplane. The Sperry works different than any other gyro. One of them, the background moves and the plane stays like this [stationary], and in the other one the background stays steady and the plane moves, it works just backwards. He [the pilot] could have been reading this backwards... they were going down, they thought they were still climbing."

Shortly after 1:00 a.m. on February 3, 1959, Holly, Valens, Richardson, and Peterson were killed when the aircraft crashed into a cornfield five miles northwest of Clear Lake shortly after takeoff. The three musicians, who were ejected from the fuselage upon impact, sustained severe head and chest injuries.[51] Holly was 22 years old.

The report did not mention a gun belonging to Holly that was found by a farmer two months after the crash. Newspaper accounts of the gun discovery fueled rumors among fans that the pilot was somehow shot, causing the crash. Another curious finding at the crash was that Richardson's body was discovered nearly 40 feet (12 metres) away from the crash while the others were found in or near the wreckage. However, an autopsy done at the request of Richardson's son in 2007 found no evidence to support the rumors. Dr. Bill Bass, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Tennessee, stated that "There was no indication of foul play," and that Richardson "died immediately."[52]

Holly's funeral was held on February 7, 1959, at the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Lubbock. The service was officiated by Ben D. Johnson, who had presided at the Hollys' wedding just months earlier. The pallbearers were Jerry Allison, Joe B. Mauldin, Niki Sullivan, Bob Montgomery, and Sonny Curtis. Some sources say that Phil Everly, one half of The Everly Brothers, was also pallbearer, but Everly said that he attended the funeral but was not a pallbearer.[53] Waylon Jennings was unable to attend because of his commitment to the still-touring Winter Dance Party. Holly's body was interred in the City of Lubbock Cemetery, in the eastern part of the city. Holly's headstone carries the correct spelling of his surname (Holley) and a carving of his Fender Stratocaster guitar.[54]

Santiago watched the first reports of Holly's death on television. The following day, she suffered a miscarriage. Holly's mother, who heard the news on the radio in Lubbock, Texas, screamed and collapsed. Because of Elena's miscarriage, in the months following the accident, some government authorities implemented a policy against announcing victims' names until after families are informed.[55] Santiago did not attend the funeral and has never visited the gravesite. She later told the Avalanche-Journal, "In a way, I blame myself. I was not feeling well when he left. I was two weeks pregnant, and I wanted Buddy to stay with me, but he had scheduled that tour. It was the only time I wasn't with him. And I blame myself because I know that, if only I had gone along, Buddy never would have gotten into that airplane."[56]

Personal life

Holly married María Elena Santiago, a New York record company receptionist, on August 15, 1958, at Tabernacle Baptist Church in his hometown of Lubbock, Texas. In 1959, Santiago was pregnant with their first child, but suffered a miscarriage immediately after Holly's death. They had only been married for six months.[57]

Peggy Sue Gerron was the inspiration behind Holly's hit song "Peggy Sue". Holly and Gerron had a flirtatious relationship, and Gerron had known Holly since her schooldays when she was dating drummer Jerry Allison. Gerron married Allison on July 22, 1958. The two newlywed couples had a shared honeymoon in Acapulco, Mexico.[58]

Holly's own marriage to Santiago was distant and tense, and the couple were supposedly headed for divorce. In late 1958, Holly had also encouraged Gerron to divorce Allison over his drunkenly behavior, but she declined. The act of divorce went against her Catholic beliefs (however, Gerron eventually did divorce Allison in 1965). In December 1958, Holly recorded a demo of one of his last songs "Peggy Sue Got Married"—about Gerron and Allison's marriage.[58]

Image and style

Holly's singing style was characterized by his vocal hiccups, a technique he acquired after hearing Elvis do it in 1955 on the Hayride show, and his alternation between his regular voice and falsetto.[59] Holly's "stuttering vocals" were complemented by his percussive guitar playing, solos, stops, bent notes, and rhythm and blues chord progressions.[60] He often strummed downstrokes that were accompanied by Allison's percussion.[12]

Holly bought his first Fender Stratocaster, which became his signature guitar, at Harrod Music in Lubbock. His innovative playing style was characterized by its blending of chunky rhythm and high string lead work. Holly played his first 1954 Stratocaster until it was stolen during a tour stop in Michigan in 1957. To replace it, he purchased a 1957 model before a show in Detroit. Holly owned four or five Stratocasters during his career.[61]

At the beginning of their music careers, Holly and his group wore business suits. When they met the Everly Brothers, Don Everly took the band to Phil's Men's Shop in New York City and introduced them to Ivy League clothes. The brothers advised Holly to replace his old-fashioned glasses with horn-rimmed glasses, which had been popularized by Steve Allen.[62] Holly bought a pair of glasses made in Mexico from Lubbock optometrist Dr. J. Davis Armistead. Teenagers in the United States started to request this style of glasses, which were later popularly known as "Buddy Holly glasses."[63]

While Holly's other belongings were recovered immediately following his fatal plane crash, there was no record of his signature glasses being found. They were presumed lost until, in March 1980, they were discovered in a Cerro Gordo County courthouse storage area by Sheriff Gerald Allen. They had been found in the spring of 1959, after the snow had melted, and had been given to the sheriff's office. They were placed in an envelope dated April 7, 1959, along with the Big Bopper's watch, a lighter, two pairs of dice and part of another watch, and misplaced when the county moved courthouses. The glasses frames were returned to Santiago a year later, after a legal contest over them with his parents. They are now on display at the Buddy Holly Center in Lubbock, Texas.[64][65]

Legacy

Buddy Holly left behind dozens of unfinished recordings — solo transcriptions of his new compositions, informal jam sessions with bandmates, and tapes demonstrating songs intended for other artists. The last known recordings, made in Holly's apartment in late 1958, were his last six original songs. In June 1959, Coral Records overdubbed two of them with backing vocals by the Ray Charles Singers and studio musicians in an attempt to simulate the established Crickets sound. The finished tracks became the first posthumous Holly single, "Peggy Sue Got Married"/"Crying, Waiting, Hoping." The new release was successful enough to warrant an album drawing upon the other Holly demos, using the same studio personnel, in January 1960.[66] All six songs were included in The Buddy Holly Story, Vol. 2 (1960).

The demand for Holly records was so great (although none saw much chart success on the US billboards), and Holly had recorded so prolifically, that his record label was able to release new Holly albums and singles for the next 10 years. Norman Petty produced most of these new editions, drawing upon unreleased studio masters, alternate takes, audition tapes, and even amateur recordings (some dating back to 1954 with low-fidelity vocals). The final "new" Buddy Holly album, Giant, was released in 1969; the single chosen from the album was "Love Is Strange."[67]

Encyclopædia Britannica stated that Holly "produced some of the most distinctive and influential work in rock music."[68] AllMusic defined him as "the single most influential creative force in early rock and roll."[69] Rolling Stone ranked him number 13 on its list of "100 Greatest Artists."[70] The Telegraph called him a "pioneer and a revolutionary [...] a multidimensional talent [...] (who) co-wrote and performed (songs that) remain as fresh and potent today."[71] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Holly at number 74 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[72]

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame included Holly among its first class in 1986. On its entry, the Hall of Fame remarked upon the large quantity of material he produced during his short musical career, and said it "made a major and lasting impact on popular music." It called him an "innovator" for writing his own material, his experimentation with double tracking and the use of orchestration; he is also said to have "pioneered and popularized the now-standard" use of two guitars, bass, and drums by rock bands.[73] The Songwriters Hall of Fame also inducted Holly in 1986, and said his contributions "changed the face of Rock 'n' Roll."[74] Holly developed in collaboration with Petty techniques of overdubbing and reverb, while he used innovative instrumentation later implemented by other artists.[12] Holly became "one of the most influential pioneers of rock and roll" who had a "lasting influence" on genre performers of the 1960s.[60]

In 1980, Grant Speed sculpted a statue of Holly playing his Fender guitar. This statue is the centerpiece of Lubbock's Walk of Fame, which honors notable people who contributed to Lubbock's musical history. Other memorials to Buddy Holly include a street named in his honor and the Buddy Holly Center, which contains a museum of Holly memorabilia and fine arts gallery. The center is located on Crickets Avenue, one street east of Buddy Holly Avenue, in a building that previously housed the Fort Worth and Denver South Plains Railway Depot.[75] In 2010, the statue was taken down for refurbishment, and construction of a new Walk of Fame began.

In 1997, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences gave Holly the Lifetime Achievement Award.[76] He was inducted into the Iowa Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame in 2000. On May 9, 2011, the City of Lubbock held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Buddy and Maria Elena Holly Plaza, the new home of the statue and the Walk of Fame.[77] On what would have been his 75th birthday, a star bearing Holly's name was placed on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[78]

Groundbreaking was held on April 20, 2017, for the construction of a new performing arts center in Lubbock, the Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Sciences, a downtown $153 million project expected to be completed in 2020.[79] Thus far, the private group, the Lubbock Entertainment and Performing Arts Association, has raised or received pledges in the amount of $93 million to underwrite the project.[80]

According to a June 2019 article in The New York Times Magazine, "virtually all" of Holly's masters were lost in the 2008 Universal fire.[81] This is disputed by Chad Kassem of Analogue Productions, who claims to have used the master tapes of Holly's first two albums in Analogue Productions reissues of these albums on LP and SACD in 2017.[82]

Influence

The Beatles

John Lennon and Paul McCartney saw Holly for the first time when he appeared on Sunday Night at the London Palladium.[83] The two had recently met and begun their musical association. They studied Holly's records, learned his performance style and lyricism, and based their act around his persona. Inspired by Holly's insect-themed Crickets, they chose to name their band "the Beatles". Lennon and McCartney later cited Holly as one of their main influences.[84]

Lennon's band the Quarrymen covered "That'll Be the Day" in their first recording session, in 1958.[85] During breaks in the Beatles' first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, on February 9, 1964, Lennon asked CBS coordinator Vince Calandra about Holly's performances; Calandra said Lennon and McCartney repeatedly expressed their appreciation of Holly.[86] The Beatles recorded a close cover of Holly's version of "Words of Love", which was released on their 1964 album Beatles for Sale (in the US, in June 1965 on Beatles VI). During the January 1969 recording sessions for their album Let It Be, the Beatles played a slow, impromptu version of "Mailman, Bring Me No More Blues" – which Holly popularized but did not write – with Lennon mimicking Holly's vocal style.[87] Lennon recorded a cover version of "Peggy Sue" on his 1975 album Rock 'n' Roll.[88] McCartney owns the publishing rights to Holly's song catalog.[89]

Bob Dylan

On January 31, 1959, two nights before Holly's death, 17-year-old Bob Dylan attended Holly's performance in Duluth. Dylan referred to this in his acceptance speech when he received the Grammy Award for Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind in 1998: "... when I was sixteen or seventeen years old, I went to see Buddy Holly play at Duluth National Guard Armory and I was three feet away from him ... and he looked at me. And I just have some sort of feeling that he was ... with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way."[90]

The Rolling Stones

Mick Jagger saw Holly performing live in Woolwich, London, during a tour of the UK; Jagger particularly remembered Holly's performance of "Not Fade Away" – a song that also inspired Keith Richards, who modeled his early guitar playing on the track. The Rolling Stones had a hit version of the song in 1964.[91] Richards later said, "[Holly] passed it on via the Beatles and via [the Rolling Stones] ... He's in everybody."[92]

Steve Marriott

From a young age, Steve Marriott was a huge fan of Holly and would mimic his hero by wearing large-rimmed spectacles with the lenses removed. Marriott wrote his first song, called "Shelia My Dear", after his aunt Shelia to whom he was close. Those who heard the song said it was played at a jaunty pace in the style of Holly and his bandmates also nicknamed him 'Buddy'.[93] Marriott also recorded a version of Kenny Lynch's song "Give Her My Regards" b/w "Imaginary Love", the B-side written by Marriott, and released as a 45-rpm in 1963 on Decca, inspired by Buddy Holly and the Crickets.[94][95] His band, Humble Pie released a cover version of "Heartbeat" on their 1969 album Town and Country.[96]

Don McLean

Don McLean's popular 1971 ballad "American Pie" was inspired by Holly's death and the day of the plane crash. The song's lyric, which calls the incident "The Day the Music Died", became popularly associated with the crash. McLean's album American Pie is dedicated to Holly.[97] In 2015, McLean wrote, "Buddy Holly would have the same stature musically whether he would have lived or died, because of his accomplishments ... By the time he was 22 years old, he had recorded some 50 tracks, most of which he had written himself ... in my view and the view of many others, a hit ... Buddy Holly and the Crickets were the template for all the rock bands that followed."[98]

Eric Clapton

The Chirping Crickets was the first album Eric Clapton ever bought; he later saw Holly on Sunday Night at the London Palladium. In his autobiography, Clapton recounted the first time he saw Holly and his Fender, saying, "I thought I'd died and gone to heaven ... it was like seeing an instrument from outer space and I said to myself: 'That's the future – that's what I want'".[99] In 1969, his supergroup Blind Faith released a cover version of Holly's "Well All Right" featuring Steve Winwood on vocals.[100]

Bobby Vee

The launch of Bobby Vee's successful musical career resulted from Holly's death; Vee was selected to replace Holly on the tour that continued after the plane crash. Holly's profound influence on Vee's singing style can be heard in the songs "Rubber Ball" – the B-side of which was a cover of Holly's "Everyday" – and "Run to Him."[101]

The Hollies

The name of the British rock band the Hollies is often claimed as a tribute to Holly; according to the band, they admired Holly, but their name was mainly inspired by sprigs of holly in evidence around Christmas 1962.[102]

Phil Ochs

In 1970, protest folk singer Phil Ochs released his sarcastic Greatest Hits (1970) album, and eventually, his live album Gunfight at Carnegie Hall (1974). During his concert at Carnegie Hall on March 27, 1970, Phil Ochs performed his "Buddy Holly Medley" comprising Holly's songs "Not Fade Away", "I'm Gonna Love You Too", "Think It Over", "Oh, Boy!", "Everyday", and "It's So Easy".[103][104] Before performing the medley, Ochs announced to the audience, "We're going to do a medley of songs of one of the greatest musicians that ever lived, a man who died prematurely, a man who had a big influence on me ... Before I became a protest and folk singer, I had memorized many other things before Pete Seeger, before Bob Dylan, before the Weavers, before anything you might have ever heard in New York City, and this is Buddy Holly."

Elton John

Elton John was musically influenced by Holly. At age 13, although he did not require them, John started wearing horn-rimmed glasses to imitate Holly.[105]

Elvis Costello

During the height of punk, Elvis Costello resembled Holly. He wore his stylized glasses and dressed like him.[106] Bob Dylan on Costello, from his 2022 book The Philosophy of Modern Song, "Elvis Costello and the Attractions were a better band than any of their contemporaries. Light years better. Elvis himself was a unique figure. Horn-rimmed glasses, quirky, pigeon-toed and intense. The only singer-guitarist in the band. You couldn't say that he didn't remind you of Buddy Holly. The Buddy stereotype. At least on the surface. Elvis had Harold Lloyd in his DNA as well. At the point of ‘Pump It Up’, he obviously had been listening to Springsteen too much. But he also had a heavy dose of 'Subterranean Homesick Blues'."[107][108]

Bruce Springsteen

In an August 24, 1978, interview with Rolling Stone, Bruce Springsteen told Dave Marsh, "I play Buddy Holly every night before I go on; that keeps me honest."[109]

Grateful Dead

The Grateful Dead performed the song "Not Fade Away" in concerts.[110]

Richard Barone

In 2016, Richard Barone released his album Sorrows & Promises: Greenwich Village in the 1960s, paying tribute to the new wave of singer-songwriters in the Village during that pivotal, post-Holly era. The album opens with Barone's version of "Learning the Game", one of the final songs written and recorded by Holly at his home in Greenwich Village, a week before his death.[111]

Film and musical depictions

Film

Holly's life story inspired a Hollywood biographical film, The Buddy Holly Story (1978); its lead actor Gary Busey received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Holly. The film was widely criticized by the rock press, and by Holly's friends and family, for its inaccuracies.[112] This led Paul McCartney (whose MPL Communications by then controlled the publishing rights to Buddy Holly's song catalog) to produce and host his own documentary about Holly in 1985, titled The Real Buddy Holly Story. This video includes interviews with Keith Richards, Phil and Don Everly, Sonny Curtis, Jerry Allison, Holly's family, and McCartney, among others.[113]

In 1987, musician Marshall Crenshaw portrayed Buddy Holly in the movie La Bamba, which depicts him performing at the Surf Ballroom and boarding the fatal airplane with Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper. Crenshaw's version of "Crying, Waiting, Hoping" is featured on the La Bamba original motion picture soundtrack.[114]

Holly's follow up to the hit song "Peggy Sue" is featured in the 1986 Francis Ford Coppola film Peggy Sue Got Married, in which a 43-year-old mother and housewife facing divorce played by Kathleen Turner is thrust back in time and given the chance to change the course of her life.

Steve Buscemi appeared as Holly in a brief cameo as a 1950s-themed restaurant employee in Quentin Tarantino's 1994 film Pulp Fiction, in which he takes Mia Wallace and Vincent Vega's orders (portrayed respectively by Uma Thurman and John Travolta).

In 1998, the post-apocalyptic film Six-String Samurai depicted Holly as a guitar-playing samurai traveling to Las Vegas to become the new king of Nevada after the death of Elvis Presley.

Television

Holly was depicted in a 1989 episode of the science-fiction television program Quantum Leap titled "How the Tess Was Won"; Holly's identity is only revealed at the end of the episode. Dr. Sam Beckett (Scott Bakula) influences Buddy Holly to change his lyrics from "piggy, suey" to "Peggy Sue", setting up Holly's future hit song.[115]

In the animated series The Venture Bros., it is implied that the elderly villains Dragoon and Red Mantle are actually Richardson and Buddy Holly, who were recruited into the supervillain organization the Guild of Calamitous Intent on the night of their supposed deaths.

The TV documentaries Without Walls: Not Fade Away (aired on Channel Four in 1996),[116] and Buddy Holly: Rave On (aired on BBC Four in 2017).[117] The 2022 documentary The Day the Music Died explores the story behind Don McLean's song "American Pie".[118]

Music

- Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story, a jukebox musical depicting Holly's life, opened in 1989.

- In 1961, Mike Berry recorded "Tribute to Buddy Holly."

- In 1980, The Clash referenced Holly in their song "If Music Could Talk" from the Sandinista! album.[119]

- In 1985, the German punk band Die Ärzte composed a song centering on Buddy Holly's glasses, titled "Buddy Holly's Brille."[120]

- In 1994, Weezer's first top 40 single in the US was titled "Buddy Holly."

- In 2006, country band the Dixie Chicks mention Buddy Holly in their song "Lubbock or Leave It." Lead singer Natalie Maines and Holly share a hometown of Lubbock, Texas.

Discography

The Crickets

- The "Chirping" Crickets (1957)

Solo

- Buddy Holly (1958)

- That'll Be the Day (1958)

References

- ^ Driggars, Alex (April 8, 2022). "Larry Holley, Eldest Brother of Buddy Holly, Dies at 96". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

- ^ "Travis Holley, One of Buddy's Brothers, Dies Thursday (Playbill by Kerns Blog)". lubbockonline.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Patricia Holley Obituary (2008) - Surrey Advertiser". www.legacy.com.

- ^ Buddy Holly: A Biography By Ellis Amburn pg. 10

- ^ a b Gribbin 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Gribbin 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Gribbin 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 6.

- ^ a b Lehmer 2003, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Wishart 2004, p. 540.

- ^ a b c Carr, Joseph & Munde, Alan 1997, p. 130.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Uslan & Solomon 1981, p. 49.

- ^ Trzcinski, Matthew (February 10, 2022). "How a John Wayne Movie Inspired Buddy Holly's 'That'll Be the Day'". CheatSheet.

- ^ "My brother, Buddy Holly". YouTube. February 24, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Amburn, Ellis (April 22, 2014). Buddy Holly: A Biography. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 101. ISBN 9781466868564 – via Google Books.

- ^ Carr, Joseph & Munde, Alan 1997, p. 131.

- ^ Buddy Holly interviewed by Dale Lowery for KTOP radio (Topeka, Kansas), 1957.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 19.

- ^ a b Gribbin 2012, p. 57.

- ^ a b Gribbin 2012, p. 58.

- ^ a b Norman 1996, p. 156.

- ^ Norman 1996, p. 127.

- ^ Moore 2011, p. 127.

- ^ a b Moore 2011, p. 128.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Lo, Ping (October 29, 2008). "The night I saw Buddy Holly and the Crickets... for free". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "Buddy Holly & The Crickets – March 1958 « American Rock n Roll The UK Tours".

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 90.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 281.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 274.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 280.

- ^ Laing 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Carr, Joseph & Munde, Alan 1997, p. 155.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 274–278.

- ^ Lloyd Webber 2015.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 276–278.

- ^ Jennings & Kaye 1996, p. 51.

- ^ Corbin, Sky 2014.

- ^ Jennings & Kaye 1996, p. 58, 59.

- ^ Jennings & Kaye 1996, p. 62.

- ^ Everitt 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Galloway, Paul (June 24, 1988). "Hit parade". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 882608515.

- ^ Denberg, Jody (January 1988). "Chantilly Lace and a Jolly Face". Texas Monthly. p. 100 – via Google Books.

- ^ Associated Press staff 1959.

- ^ "Big Bopper rumours put to rest by autopsy". The Associated Press. March 7, 2007 – via CBC.

- ^ Amburn, Ellis 2014, p. 347.

- ^ Amburn, Ellis 2014, p. 348–52.

- ^ Suddath 2009.

- ^ Kerns 2008.

- ^ Pisula, Theresa; Lovelace, Tommy (June 1, 2000). "Interview with Maria Elena Holly". HoustonTheatre.com. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "My love for Buddy Holly and how his death stopped us marrying - by the". Evening Standard. April 11, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff 2001.

- ^ a b Henderson & Stacey 2014, p. 296.

- ^ Hunter 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Norman 1996, p. 144.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 175.

- ^ "Holly's glasses returned to family". The Beaver County Times. March 12, 1980. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ "Eyeglasses returned". The Prescott Courier. March 22, 1981. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Goldrosen, John (1979). The Buddy Holly Story. Quick Fox. ISBN 978-0-825-63936-4

- ^ "Buddy Holly- Giant". discogs. 1969. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Crenshaw, Marshall 2015.

- ^ Eder, Bruce 2015.

- ^ Mellecamp 2011.

- ^ Norman, Phillip 2015.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame staff 2015.

- ^ Songwriters hall of Fame staff 2002.

- ^ Buddy Holly Center staff 2014.

- ^ Hollywood Reporter Staff 1997.

- ^ Kerns 2011.

- ^ Duke, Alan 2011.

- ^ "Lubbock's $153M Buddy Holly Hall Due to Open in 2020". constructionequipmentguide.com. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ Kerns, William (April 1, 2017). "Restaurant Partnership, Groundbreaking Date Announced for Buddy Holly Hall". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (June 11, 2019). "The Day the Music Burned: It Was the Biggest Disaster in the History of the Music Business — and Almost Nobody Knew". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Crickets/Buddy Holly - Buddy Holly". Acoustic Sounds. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Humphries 2003, p. 73.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 67–70.

- ^ Gaar 2013, p. 238.

- ^ Harris 2014, p. 192–193.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2014, p. 186.

- ^ Blaney, John 2005, p. 163.

- ^ BBC News staff 2003.

- ^ Shelton 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Amburn, Ellis 2014, p. 274.

- ^ Hewitt, Paolo; Hellier, John (2004). Steve Marriott: All Too Beautiful. Helter Skelter Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-900924-44-3.

- ^ "Steve Marriott - Give Her My Regards". Discogs.

- ^ "Making Time- Steve Marriott - Give All She's Got". www.makingtime.co.uk. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Wall, Mick (July 29, 2020). "Humble Pie: a guide to their best albums". louder. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Crouse, Richard 2012, p. 86.

- ^ McLean 2015.

- ^ Clapton, Eric 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (January 11, 2023). "Top 10 Jeff Beck Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Dean, Maury 2003, p. 73.

- ^ Eder, Bruce 1996.

- ^ "Buddy Holly Medley (1970/Live At Carnegie Hall)". YouTube. October 30, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Sanchez, Joshua (March 26, 2020). "Phil Ochs: the doomed folk singer who woke up from the American dream". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Goldrosen 1979, p. 8.

- ^ Crandall, Bill (February 28, 2003). "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Elvis Costello". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "Bob Dylan: 'Elvis Costello was light years better'". faroutmagazine.co.uk. November 7, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Dylan, Bob (November 1, 2022). The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4870-6.

- ^ Deardorff II, Donald 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Meriwether 2013, p. 134.

- ^ Gerstenzang, Peter (August 4, 2016). "Richard Barone Breathes New Life Into the Golden Age of Village Folk". Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ Flippo, Chet (September 21, 1978). "The Truth Behind 'The Buddy Holly Story'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Lehmer 2003, p. 174–176.

- ^ Green 1999, p. 267.

- ^ Phillips & Garcia 1996, p. 358.

- ^ "Without Walls: Not Fade Away". Internet Archive. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ "Buddy Holly: Rave On". BBC Four. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Day the Music Died (2022)". imdb. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Fletcher 2012, p. 174.

- ^ Leim, Christof; Hömke, Andrea (April 14, 2019). "Time Jump: On April 7, 1959 Buddy Holly's Glasses Are Found in Iowa". U Discover (in German). Retrieved February 13, 2021.

Sources

- Nancy Sinatra (2013)[citation needed]

- Pomplamoose (2016), on Pomplamoose Live[citation needed]

- Youn Sun Nah (2003), on her album Elles̤[citation needed]* Amburn, Ellis (2014). Buddy Holly: A Biography. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-14557-6.

- "Iowa Crash Kills 3 Singers; Rock 'n' Roll Stars and Pilot Die as Chartered Craft Falls After Its Take-Off". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1959. p. 1. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- "Sir Paul's fortune boosted". BBC News. 2003. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Blaney, John (2005). John Lennon: Listen to This Book. John Blaney. ISBN 978-0-954-45281-0.

- "The Buddy Holly Center – History". The Buddy Holly Center. The City of Lubbock. 2014. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- Carr, Joseph; Munde, Alan (1997). Prairie Nights to Neon Lights: The Story of Country Music in West Texas. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-365-8.

- Clapton, Eric (2010). Eric Clapton: The Autobiography. Random House. ISBN 978-1-409-06039-0.

- Corbin, Sky (2014). "The Waylon Jennings Years at KLLL (Part Five)". KLLL. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- Crenshaw, Marshall (2015). "Buddy Holly (American Musician)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Crouse, Richard (2012). Who Wrote The Book of Love?. Random House Digital. ISBN 978-0-385-67442-3.

- Dean, Maury (2003). Rock and Roll: Gold Rush. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-875-86227-9.

- Deardorff II, Donald (2013). Bruce Springsteen: American Poet and Prophet. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-88427-4.

- Duke, Alan (2011). "Buddy Holly's Officially a Hollywood Star". CNN. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Eder, Bruce (1996). "Just One More Look at The Hollies". Goldmine. 22 (14).

- Eder, Bruce (2015). "Buddy Holly – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Eiss, Harry (2013). The Mythology of Dance. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-443-85288-3.

- Everitt, Rich (2004). Falling Stars: Air Crashes That Filled Rock and Roll Heaven. Harbor House. ISBN 978-1-891799-04-4.

- Fletcher, Tony (2012). The Clash: The Music That Matters. Music Sales Group. ISBN 978-0-857-12749-5.

- Gaar, Gillian (2013). 100 Things Beatles Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Triunph Books. ISBN 978-1-623-68202-6.

- Goldrosen, John (1979). The Buddy Holly Story. Quick Fox. ISBN 978-0-825-63936-4.

- Green, Stanley (1999). Hollywood Musicals Year by Year. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-00765-1.

- Gribbin, John (2012). Not Fade Away: The Life and Music of Buddy Holly. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-848-31384-2.

- Harris, Michael (2014). Always on Sunday: An Inside View of Ed Sullivan, the Beatles, Elvis, Sinatra & Ed's Other Guests. Word International.

- Henderson, Lol; Stacey, Lee (2014). Encyclopedia of Music in the 20th Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92946-6.

- "Highest Honor". Hollywood News Reporter. 1997. Retrieved March 24, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Humphries, Patrick (2003). Elvis The No. 1 Hits: The Secret History of the Classics. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-740-73803-6.

- Hunter, Dave (2013). The Fender Stratocaster: The Life & Times of the World's Greatest Guitar & Its Players. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-760-34484-2.

- Jennings, Waylon; Kaye, Lenny (1996). Waylon: An Autobiography. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-51865-9.

- Jones, Steve (2014). Start You Up: Rock Star Secrets to Unleash Your Personal Brand and Set Your Career on Fire. Greenleaf Book Group. ISBN 978-1-626-34070-1.

- Kerns, William (2008). "Buddy and Maria Elena Holly Married 50 Years Ago". LubbockOnline.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- Kerns, William (2011). "Buddy and Maria Holly Plaza dedication attracts large turnout". Lubbock-Online.com. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- Laing, Dave (2010). Buddy Holly. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22168-1.

- Lehmer, Larry (2003). The Day the Music Died: The Last Tour of Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens. Music Sales Group. ISBN 978-0-825-67287-3.

- Margotin, Phillipe; Guesdon, Jean-Michael (2014). All The Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release. Black Dog, Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-603-76371-4.

- McLean, Don (2015). "Don McLean: Buddy Holly, rest in peace". CNN. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- Mellecamp, John (2011). "100 Greatest Artists". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Meriwether, Nicholas (2013). Studying the Dead: The Grateful Dead Scholars Caucus, an Informal History. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-89125-8.

- Moore, Gary (2011). Hey Buddy: In Pursuit of Buddy Holly, My New Buddy John, and My Lost Decade of Music. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932-71497-5.

- Norman, Phillip (1996). Rave on: The Biography of Buddy Holly. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80082-0.

- Norman, Philip (2011). Buddy: The Definitive Biography of Buddy Holly. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-447-20340-7.

- Norman, Philip (February 3, 2015). "Why Buddy Holly will never fade away". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Phillips, Mark; Garcia, Frank (1996). Science Fiction Television Series: Episode Guides, Histories, and Casts and Credits for 62 Prime-Time Shows, 1959 through 1989. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-61030-6.

- Riley, Tim (2011). Lennon: The Man, the Myth, the Music. Random House. ISBN 978-1-448-11319-4.

- "Buddy Holly Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- "Buddy Holly Biography". Rolling Stone. 2001. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2007). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever. Vol. 1. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-33845-8.

- Shelton, Robert (2011). No Direction Home – The Life And Music of Bob Dylan. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-857-12616-0.

- "Buddy Holly". Songwriters Hall of Fame. American National Academy of Popular Music. 2002. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Suddath, Claire (2009). "The Day the Music Died". Time. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- Uslan, Michael; Solomon, Bruce (1981). Dick Clark's the First 25 Years of Rock & Roll. Dell Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-440-51763-4.

- Lloyd Webber, Julian (2015). "Buddy Holly's heartbreak songs". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Wishart, David (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-80-324787-1.

Further reading

- Bustard, Anne (2005). Buddy: The Story of Buddy Holly. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4223-9302-4.

- Comentale, Edward P. (2013). Chapter Five. Sweet Air: Modernism, Regionalism, and American Popular Song. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07892-7.

- Dawson, Jim; Leigh, Spencer (1996). Memories of Buddy Holly. Big Nickel Publications. ISBN 978-0-936433-20-2.

- Gerron, Peggy Sue (2008). Whatever Happened to Peggy Sue?. Togi Entertainment. ISBN 978-0-9800085-0-0.

- Goldrosen, John; Beecher, John (1996). Remembering Buddy: The Definitive Biography. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80715-7.

- Goldrosen, John (1975). Buddy Holly: His Life and Music. Popular Press. ISBN 0-85947-018-0

- Laing, Dave (1971–2010). Buddy Holly. Icons of Pop Music. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-22168-4. OCLC 611172616.

- Mann, Alan (1996). The A-Z of Buddy Holly. Aurum Press (2nd edition). ISBN 1-85410-433-0 or 978–1854104335.

- McFadden, Hugh (2005). "Elegy for Charles Hardin Holley". Elegies & Epiphanies: Selected Poems. Belfast: Lagan Press.

- Norman, Phillip (1996) Rave On: The Biography of Buddy Holly. Simon & Schuster Publishing. ISBN 0684800829.

- Peer, Elizabeth and Ralph II (1972). Buddy Holly: A Biography in Words, Photographs and Music Australia: Peer International. ASIN B000W24DZO.

- Peters, Richard (1990). The Legend That Is Buddy Holly. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-285-63005-9 or 978–0285630055.

- Rabin, Stanton (2009). OH BOY! The Life and Music of Rock 'n' Roll Pioneer Buddy Holly. Van Winkle Publishing (Kindle). ASIN B0010QBLLG.

- Tobler, John (1979). The Buddy Holly Story. Beaufort Books.

- VH1's Behind the Music The Day the Music Died interview with Waylon Jennings

External links

- Buddy Holly news archives at the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal

- Buddy Holly at AllMusic

- Buddy Holly at IMDb

- Buddy Holly – sessions and cover songs

- Buddy Holly recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings

- Interview with Norman Petty in International Songwriters Association's "Songwriter Magazine"