Brazilian jurisdictional waters

Brazil's jurisdictional waters (Portuguese: águas jurisdicionais brasileiras, AJB), also known as the Blue Amazon (Amazônia Azul),[a] are the riverine and oceanic spaces over which Brazil exerts some degree of jurisdiction over activities, persons, installations and natural resources through the Brazilian Navy's supervision.[2] They comprise internal waters, the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and waters overlying the continental shelf where it exceeds the EEZ (beyond 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) from the shore), for a total claimed area of 5,669,852.41 square kilometers, equivalent to 67% of the country's territory on land. 2,094,656.59 km2 consist of the post-EEZ shelf,[3] a stretch of seabed yet to be recognized by the United Nations (UN). Brazilian claims of jurisdiction over its overlying waters are controversial, as they lie in the high seas.[4]

As a party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into force in 1994, Brazil has sought to expand of its maritime boundaries within the Convention's parameters. LEPLAC, a joint surveying project by the country's navy, Petrobras and the scientific community, provided the basis for an extended shelf claim submission to the UN in 2004. That same year, the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago was included in the EEZ. Shelf extension proposals have been revised and by 2018 included the Rio Grande Rise. Geologically, Brazil's legal continental shelf is for the most part a divergent continental margin formed by the breakup of the African and South American continents, leaving major reserves of petroleum and natural gas in the pre-salt layer of their sedimentary basins. Brazil is nominally self-sufficient in crude oil[5] and controlled the world's 14th largest reserves in 2018,[6] most of which are extracted at sea.

The Atlantic Ocean under Brazilian jurisdiction has two prevailing surface currents, Brazil and North Brazil. Their warm, nutrient-poor waters are home to a diverse fauna, although each species has a relatively low biomass.[7] 26.4% of the EEZ was under protected areas in 2021,[8] mostly in the remote archipelagos of St. Peter and St. Paul and Trindade and Martim Vaz.[9] Almost all of Brazil's international trade is conducted through the sea by foreign-flagged vessels. Coastal navigation has a modest share of internal trade, even though the densely populated Brazilian coast is the longest in the South Atlantic. There are no official statistics on the maritime economy.[10] An estimated 2.67% of Brazil's gross domestic product (GDP) was directly linked to the sea in 2015, mostly in the service sector.[11] Renewable energy generation, seabed mining and biotechnology have untapped potentials.

The "Blue Amazon" is a less formal name given by the Navy since 2004. By analogy with the "Green" Amazon, it is presented as a vast territory whose natural wealth draws international greed and therefore must be militarily protected. The military's role is extensive, as the Navy is both a conventional naval force and a coast guard (reinforced in these roles by the Air Force), controls the Merchant Marine's officer training, fields research vessels and scientific outposts and receives a share of the royalties of oil production. Nonetheless, their message has not convinced decision makers to finance the ambitious late 2000s military investment programs.[12][13] On a broader horizon, the concept of a "Blue Amazon" intends to recover a national self-image as a maritime nation after a century faced towards development of the interior.[14]

Definition

International law

Brazilian regulation on maritime spaces follows UNCLOS, a codification of international maritime law which came into force in 1994.[15][16] This Convention, ratified by 168 states as of 2022,[16] unifies centuries of rulemaking on interstate disputes over control of the seas.[17] It organizes the sea off the coast of sovereign states in multiple zones: the territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.[15][16] Distances are measured in nautical miles from baselines along the coast. There are two kinds of baseline: normal lines, which follow the low-water line as plotted on official charts, or straight lines where the coast is too jagged or island-strewn.[18]

The territorial sea extends up to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres) from baselines and grants coastal states sovereignty over the airspace, water column, seabed and subsoil.[19] Each of these spaces is treated separately in the other maritime zones.[20] In the contiguous zone, at 12 to 24 miles from baselines, a coastal state does not have full sovereignty, but may take measures to prevent or repress unlawful activities in its territory or territorial sea. The contiguous zone is part of the EEZ, which has a width of 188 miles, from the limit of the territorial sea until a distance of 200 nmi (370 km) from baselines. This area gives a coastal state jurisdiction over the exploitation, conservation and management of its waters, seabed and subsoil.[16][21] The high seas begin at the EEZ's outer limit.[22]

The continental shelf as defined in international law is distinct from the geological continental shelf and consists in an area of seabed and its subsoil, excluding the overlying water column, over which a coastal state has sovereign rights over its natural resources. It extends "to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines", as defined in the UNCLOS.[23] If a coastal state's continental margin extends beyond 200 nmi, it may propose to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), an international organ created by the UNCLOS, an extension up to a maximum of 350 nmi,[24][b] or until "100 nautical miles from the 2,500 metre isobath, which is a line connecting the depth of 2,500 metres". The applicant must conduct a geological survey and provide information on the foot of the continental slope.[26][27] The CLCS analyzes this proposal and issues recommendations on the area to be designated as a continental shelf. The appliant may disagree and propose revisions, but the limits of its shelf are only accepted on international law when a final limit on which the CLCS agrees is deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations.[28][c]

Brazilian law

The term "Brazilian jurisdictional waters" (águas jurisdicionais brasileiras, AJB) exists in legislation on 1941 at the earliest, although it was less common than "Brazilian waters", "waters of the territorial sea" or "territorial waters".[30][31] The territorial sea has had a legal definition since 1850, an exclusive fishing regime since 1938, a continental shelf ("undersea shelf") since 1950,[32][33] and a contiguous zone since 1966.[32][34] The territorial sea and continental shelf were designated as federal property in the 1967 Constitution.[35] In 1963, France contested Brazil's exclusive rights to lobster fishing in its continental shelf by contending that this animal moves through the water column and is therefore not a seabed resource. Both sides moved warships to the Northeastern seas in the so-called "Lobster War", and the lobster debate was taken into account at the UNCLOS.[36][37]

Law no. 8,617 of January 4, 1993 defined Brazil's maritime zones according to the UNCLOS definitions, and Decree no. 1,530 of June 22, 1995 reproduced the convention's text, making it enforceable within the country.[15] When ratifying the convention, Brazil also announced any foreign military operations within its EEZ must be notified in advance.[38] The concept of AJB was becoming commonplace in legislation since a 1987 law on the prohibition of whaling within the AJB. Other legislative acts used expressions such as "waters under Brazilian jurisdiction", "waters under national jurisdiction" and "Brazilian jurisdictional marine waters", but the Navy took a liking to AJB. This term was used for many years without an explicit definition until the Maritime Authority's Norms for the Operation of Foreign Waters in Brazilian Jurisdictional Waters (Normas da Autoridade Marítima para Operação de Embarcações Estrangeiras em Águas Jurisdicionais Brasileiras – NORMAM-04/2001 (Ordinance 61/DPC, September 22, 2001):[39]

Brazilian jurisdictional waters (AJB) are, as follows: a) maritime waters covering a strip twelve nautical miles in width, measured from the low-water line of the Brazilian continental and insular coastline, as indicated in large-scale nautical charts officially recognized in Brazil, and which constitute the Territorial Sea; b) maritime waters covering a strip which extends from twelve to two hundred nautical miles, counted from the baselines on which the Territorial Sea is measured, which comprise the Exclusive Economic Zone; c) waters overlying the Continental Shelf when it exceeds the limits of the Exclusive Economic Zone; and d) internal waters, comprising internal waterways, considered as rivers, lakes, canals, lagoons, bays, bights and maritime areas deemed to be sheltered"[d]

Brazilan law regulates maritime traffic, environmental conservation, natural resource exploitation and scientific research in the AJB.[40][41] The Navy has the jurisdiction to complete and expound on the gaps in national maritime legislation, and therefore, definitions given in its norms prevail over others.[41][e] Matching definitions have been given in other editions of the NORMAM and in the 2014 Navy Basic Doctrine, which further established that the AJB cannot be considered part of the high seas. Presidential decrees and the National Defense White Paper, which was ratified by Congress in 2018, have accepted the Navy's definition.[44][45]

Waters overlying the extended continental shelf

Some legal scholars have criticized the Brazilian state's claim of jurisdiction over the water column overlying its extended continental shelf. Beyond 200 nmi, the water column is part of the high seas, even when its underlying seabed belongs to a state's continental shelf.[46][47][48] At the International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, Alexandre Pereira Silva summarized in 2020 that the concept of AJB is incompatible with the UNCLOS.[48] Tiago V. Zanella, an author on maritime law,[47] does not dismiss the concept's "enormous strategic importance" for the country,[49] but considers the hypothetical case of a foreign whaling vessel in the waters overlying the extended continental shelf, over 200 nmi from coastal baselines. Brazilian law requires the Navy to impede this vessel's illegal activities in the AJB. The vessel's owners could resort to an international court, such as the International Court of Justice or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, which would rule in their favor. As a party to the UNCLOS, Brazil would have to comply with this ruling.[50]

Naval officer Alexander Neves de Assumpção, in his thesis for the Naval War College, concedes there is a risk of naval commanders being led to infringe on international treaties ratified by Brazil. Nonetheless, he contended that "the concept of AJB need not be changed", as it is already moderated in legislation by the expressions "jurisdiction, to some degree", "for the purposes of control and oversight" and "within the limits of national and international law". To oversee exploitation of the seafloor, Brazil would still have a limited jurisdiction, not to be conflated with sovereignty, over its overlying waters, even when they lie in the high seas. No country has contested Brazil's definition, and Argentina and Chile have likewise claimed jurisdictions beyond what was given in the UNCLOS. What remained to be done was to draft norms clarifying which kinds of oversight are allowed.[51]

Blue Amazon

Admiral Roberto de Guimarães de Carvalho, commander of the Brazilian Navy in 2004, published an opinion column titled "A outra Amazônia" ("The other Amazon"), in which he was the first to use the term "Amazônia Azul" ("Blue Amazon"), drawing a comparison with the "Green Amazon" i.e. the Legal Amazon. The Blue Amazon was defined as the ocean strip as far as 200 nmi from the coast, together with the extended continental shelf and its overlying waters, which is the same definition as that of the jurisdictional waters. The Blue Amazon is a "less technical and more playful" term, and the expression that does exist in legislation is still águas jurisdicionais brasileiras.[52][53][f] The two Amazons are not under the same legal regime: Brazil has full sovereignty over the Green Amazon, but only over natural resources in its EEZ and continental shelf.[54]

In his opinion piece, the admiral deplored the ignorance of national public opinion over the strategic and economic significance of the sea area to which the nation is entitled, despite 80% of the population living within 200 km from the shore. The Green Amazon had recently received government initiatives such as the Calha Norte Project and the Amazon Surveillance System, for which there were no correspondents in the Blue Amazon, despite its equally vast area and economic potential. According to his numbers, 95% of external trade and 80% of oil production were in the sea; "we are so reliant on maritime traffic that it constitutes one of our great vulnerabilities".[55]

According to its creator, the concept does not compete with the original Amazon and merely takes advantage of its popular awareness.[56] The Navy has also partaken in military expansion in the Green Amazon, although at a slower pace than other arms, as it remains focused on blue waters.[57] Navy and Army officers are willing to consider the "two Amazons" as a whole, even after considering their differences. Several external threats are deemed common to both.[58] "International greed" over natural resources is central to the military's vision of the Green Amazon,[59] and admiral Carvalho assumes that "any wealth ends up as a target of covetousness, imposing on its owner the burden of protection".[55] This then leads to calls for increased military presence and surveillance in both Amazons to deter threats to national sovereignty.[60][61]

Objectives

The Blue Amazon can be defined as an instrument of propaganda to sensitize public opinion,[62] a "banner raised by the Brazilian Navy", created to foster "the maritime mentality of the Brazilian population".[63] According to José Augusto Fontoura Costa, a professor at the Law School of the University of São Paulo, the Blue Amazon's line of thought places investments into naval defense as the material condition to enforce possession of resources which have been secured on paper. This rhetoric is charged with the Navy's ambitions for a greater share of the federal budget and the public's attention. Therefore, it has "sophisms and weaknesses inherent to any discourse of political action". Even then, it "helps to redefine the perception of the Brazilian Armed Forces and retrieve extremely relevant questions on security and defense into national debate", bringing "many discussions formerly restricted to military and diplomatic strategists into public opinion", which might even result in the concept slipping from their "practical and semantic control".[64]

In his dissertation at the War College (the Escola Superior de Guerra), Matheus Marreiro contended that the concept is part of the Navy's political initiative to accrue "popular support for the creation of a maritime strategy, for attempts to expand national maritime boundaries and for the acquisition of new naval assets for defense of this space and resources". In the Navy's geopolitical discourse, the South Atlantic is presented as a natural zone of Brazilian influence and military power projection.[65] This is not necessarily the only geopolitical paradigm for the South Atlantic, and the region can also be studied from the perspective of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone, environmentalist discourse and foreign approaches, such as Argentina's "Pampa Azul".[66] The Navy does recognize multiple dimensions (political-strategic, scientific, environmental and economic) for the Blue Amazon.[67]

Publicity

The Navy undertakes a national awareness campaign to divulge its concept.[68] After admiral Carvalho's column in 2004, the topic was covered by televised reports and Roberto Godoy's writings for the Estado de S. Paulo. However, journalist Roberto Lopes assessed the Navy hadn't achieved the desired impact on the public. The topic was ignored by independent media outlets and could not find sufficiently credible spokespersons in the Rio de Janeiro-São Paulo-Belo Horizonte-Brasília axis. The Blue Amazon's meaning wasn't obvious to all and had to be explained to its public or else it could be mistaken for a naval initiative in the Green Amazon. Furthermore, the "emphasis naval chiefs lent to the enormous dimensions of the maritime area under Brazil's responsibility seemed perfectly clear and understood, but what was missing was an element of persuasion regarding the threat lurking against it".[69]

The Maritime Mentality Program (Programa de Mentalidade Marítima, Promar) promotes lectures in universities and research institutions, writing contests and the publication of books such as Amazônia Azul - O mar que nos pertence ("Blue Amazon - The sea that belongs to us") and O mar no espaço geográfico brasileiro ("The sea in Brazilian geographic space"). The latter was given out at schools.[70] The National Institute of Industrial Property recognized Amazônia Azul as a Navy trademark in 2009.[71] A public enterprise founded in 2012 to contribute to the Submarine Development Program was named Amazônia Azul Tecnologias de Defesa S.A., also known as Amazul.[72] The 1st International Forum on Bay Management, held in Salvador in 2014, declared Todos os Santos Bay as the capital of the Blue Amazon.[73] In 2015 Congress designated November 16, the date UNCLOS came into force in 1994, as "National Blue Amazon Day".[74]

In spite of these efforts, only 6% of the public knew the concept of the Blue Amazon and another 18% had heard of it in 2014, according to an opinion poll commissioned by the Navy Command and conducted by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. 60% of respondents agreed the Navy had a significant contribution to the country, but only 10% could cite examples of its actions. Maritime transport, oil production and international maritime law are topics largely unknown to the general public. Naval intellectuals deplore this lack of a "maritime mentality" in the public since the 1970s. In this perspective, the public's "imaginative geography" had once emphasized the sea in the colonial and imperial periods. Over time, socioeconomic factors and internal and external factors shifted the focus of collective imagination and elite projects (the March to the West, transfer of the capital to Brasília, prioritization of road transport and so on) towards the continental interior. The Blue Amazon is a new paradigm aiming to make Brazilians once again see themselves as a maritime nation.[14]

At first the borders of the Blue Amazon and even its archipelagos were not marked in Brazilian atlases.[75] Starting on 2023–2024, several broadcasters such as Record, Correio Braziliense, Empresa Brasil de Comunicação, Band, CNN Brasil, Rede TV and Jovem Pan included maps with the Blue Amazon in their schedule.[76] Several of them shade the area in their weather forecast maps. The 2024 School Atlas published by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE) included the "new eastern limit of Brazil's coastal-marine system". This change was publicized in seminars held on coastal states.[77]

Delimitation

The Brazilian coast measures 7,491 km,[78] the longest in the South Atlantic.[g] Its baselines project, in the Navy's numbers, an area of 3,575,195.81 km2 within the 200 nmi strip, including a territorial sea measuring 157,975.47 km2 and a contiguous zone of 325,328.34 km2. 2,094,656.59 km2 of extended continental shelf are added to this number to reach a total of 5,669,852.41 km2.[3] This corresponds to 67% of national territory (8.5 million km2) and 1.1 times the size of the Legal Amazon (5.2 million km2).[67] As the AJB also include internal waters,[80] around 60 thousand kilometers of waterways can be counted in its extent.[81] The 5.7 million km2 total claim is reached when counting the most recent (2018) revised proposals for the extended continental shelf.[82] Earlier proposals reached a total of 4,451,766 km2.[83]

This area has two international maritime boundaries, one with French Guiana and another with Uruguay, both of which are defined by rhumb lines (which cross the meridians at a constant angle) starting from the border: near the Oyapock River, for the former, and Chuí Lighthouse, for the latter. These limits were defined in 1972 with Uruguay and 1981 with France.[84]

Territorial sea

Since the 19th century, the Brazilian territorial sea was defined as a three-mile strip along the coast. Exclusive fishing rights were at at 12 nmi from the shore in 1938.[32][85] A presidential decree added a further three miles of territorial sea in 1966, in a "six miles plus six miles" regime, comparable to a contiguous zone and exclusive fishing rights zone, as far as 12 nmi from the shore.[35] The territorial sea was once again extended in 1969 to a width of 12 nmi.[86][87]

In the following year, Emílio Garrastazu Médici's government claimed a territorial sea as far as 200 nmi, spanning 3.2 million km2 of the ocean. All of its seabed, subsoil and airspace were to be placed under Brazilian sovereignty.[88] At a time when the ruling military dictatorship envisioned great power status,[89] this decision answered fishing interests and fears of foreign activity (military exercises and exploitation of recently discovered oil fields off the coast of Rio de Janeiro).[90] Public opinion, riding a wave of patriotic fervor (ufanismo), responded favorably. Other Latin American countries endorsed this measure,[91] which was not without precedent, as Argentina and Uruguay had made similar declarations.[92]

Contemporary international law defined no maximum width for the territorial sea, but in the early 70s most states, including traditional maritime powers, recognized no jurisdiction beyond 12 nmi from the shore.[93] Therefore, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs received letters of protest from the United States, the Soviet Union and nine other industrialized states. The Brazilian fleet, with a mere 57 ships of significant tonnage, lacked the effective capability to patrol the full extent of the claims.[94] When Brazil signed the UNCLOS, it gave in to great power pressures, in the opinion of diplomat Luiz Augusto de Araújo Castro.[95] Once the treaty was harmonized with national legislation in 1993, the Brazilian government retracted the limits of its territorial sea, from 200 to 12 nmi, but secured a 200-mile EEZ.[18][96]

EEZ

The University of British Columbia's Sea Around Us database quantifies a Brazilian EEZ spanning 2,400,918 km2 projected from the continental shore, 468,599 km2 surrounding the Trindade and Martim Vaz Archipelago, 363,373 km2 surrounding the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago and 413,641 km2 surrounding the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago.[97] Official Brazilian numbers are 3,539,919 km2 of total EEZ area,[98] the world's 11th largest,[99] with a water volume of 10 billion cubic meters.[7] Nonetheless, this is a relatively small area compared to the length of the coast,[78] as Brazil has few islands at major distances from the coast. The archipelagos of Trindade and Martim Vaz and Saint Peter and Saint Paul have minimal land areas, but project a quarter of the EEZ.[78]

Article 121 of UNCLOS confers an EEZ and continental shelf to islands, but denies such privileges to "rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own".[100][78] Among Brazil's oceanic islands, only Fernando de Noronha, Trindade and Belmonte (in Saint Peter and Saint Paul) are permanently inhabited.[101][102] Fernando de Noronha has the largest population, 3,167 in the 2022 census.[103] Trindade and Saint Peter and Saint Paul have research outposts established by the Navy.[102] Rocas Atoll has no more than an automatic lighthouse.[104] UNCLOS recognized it within Fernando de Noronha's jurisdiction, just as the Island of Martim Vaz was included in Trindade's.[105] However, Colombian representatives in a continental shelf dispute with Nicaragua pointed in 2019 that Brazil claims Rocas as an island and note the official Brazilian map has an EEZ projecting from the atoll.[106]

Occupation of St. Peter and St. Paul

Extending the EEZ is an openly declared objective of the Navy's presence in both Trindade and Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Brazilian sovereignty over Trindade was once contested by the United Kingdom in 1895–1896, and a permanent presence is maintained since 1957, with a population of 36 military personnel in 2023.[107][108] On the other hand, Saint Peter and Saint Paul was a neglected territory with no records of human inhabitation.[109] Only after UNCLOS came into force did the Navy's command take serious measures to occupy the are. The Archipelago Program (Proarquipélago), organized in 1996, installed a scientific station in Belmonte Islet and changed the site's toponymy from "Saint Peter and Saint Paul Rocks" to "Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago".[101][110]

The station has room for four researches and/or seamen over 15-day periods. Conditions for habitation are poor: researches are only allowed after undergoing survival training, and a ship is kept on standby to aid the station, which is about 1,000 km from the coast. The islets and rocks have a maximum width of 420 meters, lack soil and drinking water and are exposed to seismic events and severe weather.[111] In the official Brazilian understanding, a permanent presence is by itself enough to distinguish an island according to Article 121, regardless of the population's biweekly rotation and difficult survival.[112]

Starting on 1995, the Navy's Directorate of Hydrography and Navigation published nautical charts with a dotted red line in the 200 nmi radius around the rocks, indicating its potential EEZ and continental shelf.[113] The Navy presented the Interministerial Commission on Marine Resources with its case in 1999, citing the precedents of Rockall, Okinotorishima, some Hawaiian islands, Clipperton, Jan Mayen and Aves. The Ministry of Foreign Relations was favorable and noted: "although the UNCLOS is clear about the rocks which cannot sustain human habitation, it cannot be denied that there is permanent occupation in the said archipelago, though its ‘inhabitants’ depend on the continent for its sustainability". Their greatest concern was having the claim challenged by other parties to the UNCLOS.[114] After securing approval from the president and the National Defense Council, in August 27 2004 Brazil submitted the coordinates of the external limits of its EEZ to the UN's Bulletin of the Law of the Sea. The area around Saint Peter and Saint Paul was formally claimed for the first time.[115]

Proarquipélago yielded rights to an area the size of Bahia,[116] whose limits are closer to Africa than South America.[117] Article 121 has its controversies, among them the South China Sea Arbitration, whose conclusions may contradict Brazil's interpretation of the legal status of Saint Peter and Saint Paul. The Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that "the mere presence of a small number of persons on a feature" that "is only capable of sustaining habitation through the continued delivery of supplies from outside" does not equate to island status under Article 121. No state has objected to Brazil's claim over the archipelago.[118]

Continental shelf

The earliest definitions of the extent of Brazil's continental shelf mixed criteria of depth (up to 200 meters) and resource exploitability.[119] The "undersea shelf" as defined in 1968 was the "seabed and subsoil of undersea regions adjacent to the coasts, but located outside the territorial sea, to a depth of 200 meters [...] or beyond this limit as far as the depth of the superjacent waters allows use of their resources".[86][120] The territorial sea's expansion to 200 nmi in 1970 absorbed the continental shelf as a distinct area, although it was still mentioned as federal property in the Constitution.[121] When Brazilian legislation was harmonized with the UNCLOS in 1993, the limits of the continental shelf remained coterminous with those of the EEZ (200 nmi), but an initiative to identify a boundary beyond this range was already underway.[122] According to diplomat Christiano Figueirôa, "the definition of the exterior limits of Brazil's continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles represents the greatest delimitation procedure in the country since the Baron of Rio Branco's era". Luiz Alberto Figueiredo sees the continental shelf as the last remaining undefined legal boundary, as definitive borders have already been decided on land.[123]

Early surveys

Field data collection to define the outer margin of the continental shelf begin in 1986. Pre-existing information, such as the previous decade's Continental Margin Reconnaissance Project (Reconhecimento da Margem Continental, REMAC), had insufficient coverage, particularly far from the shore, to substantiate claims on the international sphere.[124] In 1988 these efforts were formalized in the Brazilian Continental Shelf Survey Plan (Plano de Levantamento da Plataforma Continental Brasileira, LEPLAC), which was conducted by the Navy through its Directorate of Hydrography and Navigation, Petrobras and the national scientific community through the Marine Geology and Geophysics Program (Programa de Geologia e Geofísica Marinha, PGGM) and several educational institutions.[125] According to admiral Armando Amorim Ferreira Vidigal, LEPLAC was the seed for the concept of a Blue Amazon.[126]

LEPLAC's first stage lasted until 1996 and employed the military research vessels Almirante Câmara (H-41), Álvaro Alberto (H-43), Sirius (H-21) and Antares (H-40), crewed by Navy specialists, civilian researchers and, during geophysical surveys, Petrobras professionals. The expeditions collected multi-channel seismic data to determine sediment thickness in the continental margin, from the geological continental shelf until 350 nmi from the baselines. Gravimetric and magnetometric data was gathered to estimate other information, including the limit between oceanic and continental crust. Bathymetric surveys identified the foot of the continental slope, the outline of the 2,500 m isobath and new marine geomorphology models. In total, LEPLAC's first stage collected 46,966 km of two-dimensional seismic lines and 89,369 km, 97,237 km and 93,604 km of bathymetric, gravimetric and magnetometric profiles. Many university research projects employed this data.[127] The handful of civilians and military personnel at the front lines of this process have been idealized in official sources as the "bandeirantes of the salt longitudes".[128]

2004 proposal

The preparation, submission and analysis of a continental shelf extension proposal is a lengthy undertaking, and the original deadline for states to submit their claims within ten years after the UNCLOS came into force (1994 to 2004) had to be extended. In December 2003 the United Nations General Assembly called on parties to the Convention to hasten their proposals. As Brazil had begun its surveys early on, it became the second coastal state and the first developing nation to submit its proposal. On May 17 2004 the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf received Brazil's proposal on the outer limit of its continental shelf, alongside five CD-ROMs with the geographical coordinates of all points used to identify the limits, all based on LEPLAC's dataset.[129][130]

Brazilian claims applied to an area of 911,847 km2 beyond the 200 nmi line, later increased to 953,825 km2 in a 2006 addendum.[131] The claims were mostly in the Amazon Fan, the North Brazilian Chain, the eastern margin of the Vitória-Trindade Ridge and the São Paulo Plateau, all the way to the maritime border with Uruguay. Brazilian specialists held five meetings with their counterparts in the CLCS, which readied a report on its recommendations in April 2007. The Commission only recognized 765,000 km2 as part of the shelf. The Brazilian state then took the political and strategic decision not to deposit these partial limits with the Secretary-General, unlike Australia, and to only deposit its limits after resolving all of its disagreements with the CLCS.[130][132]

The United States government, despite not having signed the Convention, announced its objections to the Brazilian proposal. According to the American representative at the UN, public and American datasets presented a sedimentary thickness and Gardiner line different from that given in Brazilian data. The US also questioned the association between the Vitória-Trindade Ridge and the Brazilian continental margin, contending that it was formed by an oceanic hotspot. As the US did not meet the UNCLOS conditions for a third party's objection, the CLCS did not consider its argumentation.[133]

Revised proposals

A second stage of LEPLAC, mostly conducted in 2009–2011, filled gaps in the data, particularly in areas where the CLCS disagreed with the original claim. The Antares and the civilian vessels MV Discoverer, MV Sea Surveyor and MV Prof. Logachev collected profiles for multibeam bathymety (92,703 km of profiles), multi-channel seismic data (11,893 km), gravimetry (81,157 km), magnetometry (76,618 km) simplified multi-channel seismic data via Mini Air Gun (61,896 km) and 3,5 kHz data (71,966 km). In addition, the expeditions launched sonobuoys and retrieved rock samples from seamounts in the Vitória-Trindade and North Brazilian chains.[134] Another program, the Prospection and Exploration of Mineral Resources in the International Area of the South and Equatorial Atlantic (Prospecção e Exploração de Recursos Minerais da Área Internacional do Atlântico Sul, Proarea), and follow-on initiatives studied the Rio Grande Rise (RGR), a region previously excluded from the claims. Early studies could not prove with certainty the region was part of the continental crust.[135] Researchers in this area meet strong currents and weather and a steep, rocky seafloor.[136]

Newer surveys underpinned three revised proposals for the southern margin (April 10 2015), concerning the coast between Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná, the equatorial margin (September 8 2017), concerning the Amazon Fan and North Brazilian Chain, and the eastern and southern margins (December 7 2018), concerning the Vitória-Trindade Ridge, the Santa Catarina Plateau and the RGR.[132] The extended continental shelf claim, adding all revised proposals, reaches a total area of 2,094,656.59 km2.[3][82]

Claiming over the RGR will territorialize part of the "Area", a maritime zone enshrined as a common heritage of mankind in the UNCLOS. Brazilian authorities believe territorialization to be a worldwide process and therefore, Brazil must expand its own maritime zones.[137] At the Interministerial Commission on Marine Resources meeting in April 30 2019, a Ministry of Foreign Affairs representative argued that "if Brazil is not proactive in this area, sooner or later, a power would show up - this would not be a country with capabilities inferior to ours - to prospect for ores, oil and gas in the RGR. It would truly be a very uncomfortable situation".[138] The CLCS accepted claims over the coasts of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, spanning around 170 thousand km2, in 2019.[139] As of August 2024 Brazil had yet to reach a final understanding with the CLCS, and the expansion of its continental shelf remained on hold.[77]

Oceanography

Geomorphology

From the Brazilian coast until the abyssal plains of the South Atlantic lies a portion of the South American continental margin, which is the transition between continental and oceanic crusts. When comparing terminology between maritime law and geography, this continental margin, which comprises a continental shelf, continental slope and continental rise, is the closest geological counterpart to a "continental shelf" as defined in the UNCLOS. The legal shelf is the entire natural projection of a coastal state into the seafloor and not just its geomorphological shelf.[140]

Most of the Brazilian continental margin is a classical divergent margin formed by the breakup of the supercontinent of Gondwana and its South American and African plates.[141] This kind of margin possesses a large continental shelf and a steep but stable incline at its slope, where accumulated sediments form the continental rise, which gently slides down with decreasing thickness until the abyssal plains.[142] Several tectonic and sedimentary processes mean these three strips are not always neatly visible, and not all of the Brazilian continental margin is the divergent South Atlantic: the far north is in the divergent Central Atlantic, and part of the equatorial region is a transform margin, in which two plates slide against each other.[143][144]

20.5% of the EEZ's area is at depths of up to 200 m, which may be considered part of the continental shelf. Deep-sea features cover the rest: the continental slope (13.3%), terraces (1.7%), submarine canyons (1.4%), the continental rise (40%), abyssal plains (29.6%), submarine fans (4.9%), seamounts (2.2%), guyots (1.4%), ridges (1.2%) and spreading ridges (1.4%). These percentages add up to more than 100%, as some features occupy the same spaces.[99]

Undersea features

Following the Brazilan coast from the north, the first major feature is the Amazon Fan. Outflow from the river forms the thickest sediment beds and the widest geomorphological shelf (up to 300 km) and margin (750 km) in the entire coast. Bathymetry follows a gradient all the way to depths of 4.800 m in the Demerara Abyssal Plain.[145] To the east lie the Maranhão Seamounts and the North Brazilian and Fernando de Noronha ridges, formed parallel to the coast by the Equatorial Atlantic's transform margin. The Fernando de Noronha Chain breaks the surface in two regions, Rocas Atoll and the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago.[146] The continental shelf measures 170 km in width at the Parnaíba River's delta, narrows to 50 km in the east, at the coast of Ceará, and even more until Cape São Roque, no Rio Grande do Norte.[147] The Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago is geologically distinct: an emerged portion of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, composed of mantle rocks exposed to the surface when tectonic forces opened faults in the oceanic crust.[148][149]

The Northeast has the narrowest stretches of continental margin (100 km) and geomorphological shelf (30–50 km),[150] down to a mere 8 km of shelf off the coast in Recife.[151] From the 10th to the 16th parallel south, this is owed to the influence of the São Francisco Craton.[152] The continental rise descends until the Brazil abyssal plain, with several features perpendicular to the coast, from north to south: the Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco and Bahia seamounts and the Ferraz Ridge.[153] The continental margin widens again from Abrolhos Bank, which the Besnard Bank connects to the Vitória-Trindade Ridge, a sequence of about 30 seamounts extending 950 km to east and peaking at their eastern end in the islands of Trindade and Martim Vaz.[150]

Further south, the continental margin exceeds 500 km in width. The Campos, Santos and Paraná sedimentary basins comprise the São Paulo Plateau, the largest marginal plateau in the Brazilian coast, which is placed between the continental slope and rise.[154] Its outer limits meet the Jean Charcot Seamounts and the São Paulo Channel. The Vema Channel and the Rio Grande Rise define the Brazil Abyssal Plain's southern limit, separating it from the Argentine Abyssal Plain.[153] The ERG spans the 28th to the 34th parallel south,[155] in a total area of 500 thousand km2, emerging from a seabed 5,000 m below sea level to 650 m at its highest.[156] Its origin and evolution are controversial.[155] It is aligned to the Paraná and Etendeka Traps and the Walvis, Gough and Tristan da Cunha ridges.[157] In the past, some portions were above sea level.[156]

The southern continental margin, from the São Paulo Plateau to the Uruguayan maritime boundary, contains the Santa Catarina Plateau, the Rio Grande Terrace, the Pelotas Basin and the Rio Grande Fan.[154]

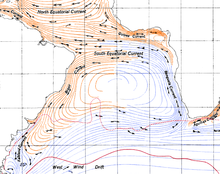

Ocean currents

The two main surface currents off the Brazilian coast are the Brazil and North Brazil (or Guiana) currents,[158] both of which have warm, nutrient-poor waters with a deep thermocline (the layer in which temperature rapidly lowers with depth).[159][160] They appear around the 11th parallel south,[161] between Recife and Maceió,[159] when the South Equatorial Current, pushed west by the trade winds, meets the South American continent and splits in two. Most of its water proceeds to the northwest towards the Caribbean, forming the North Brazil Current, and the remainder flows southwest, forming the Brazil Current. Both run parallel to the coast.[162][161] The North Brazil Current achieves speeds of 1–2 m/s, pushing the Amazonas River's plume, which provides a fifth of the global fresh water discharge into the ocean, to the northwest. Amazonian waters may be found up to 320 km from the coast.[163]

The Brazil Current is the western arm of the South Atlantic Gyre, a counterclockwise cycle of currents between South America and Africa. It flows until the latitudes of 35° to 40° S, where it meets the colder waters of the Falkland Current and both turn to the east, forming the South Atlantic Current. The Gyre returns to South America through the South Equatorial Current. The Brazil Current's surface water mass is known as the Tropical Water, with a 18 °C to 28 °C temperature range and an average salinity of 35.1 to 36.2 ppm. These values are simlar to its North Atlantic counterpart, the Gulf Stream. It is, however, slower, with a speed below 0.6 m/s. Its depth in the water column reaches 200 m on the edge of the continental shelf.[164][161]

In the Southern and Southeastern regions, the Brazil Current draws closer and further from the coast throughout the year, defining a strong seasonal pattern in water temperature and salinity.[160] In winter, the Falkland Current may reach as far north as the 24th parallel south.[159] Its water mass, known as the Subantarctic Water, mixes with the Tropical Water to form the South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), which, as a colder and denser mass, forms a layer beneath the Tropical Water in the Brazil Current. Certain points in the coast (Cape Frio and Cape Santa Marta) are subject to upwellings of the SACW when northeasterly winds push surface waters.[165][166]

In the Santos Basin the Tropical Water has concentrations of 4.19 ml/L of dissolved oxygen, 0.02 μmol/L of phosphate, 1.10 μmol/L of nitrate and 2.04 μmol/L of silicate. In contrast, the SACW has 5.13 ml/L of oxygen, 0.51 μmol/L of phosphate, 6.14 μmol/L of nitrate and 5.12 μmol/L of silicate.[167] At the 20th parallel south, the SACW extends to a depth of 660 m in the first semester. Further depths contain the Antarctic Intermediate Water (700–1,200 m), North Atlantic Deep Water (1,200–2,000 m) and Antarctic Bottom Water.[168]

Climate

Brazilian jurisdictional waters have three climate patterns: northern, from Cape Orange, Amapá to Cape Branco, Paraíba,central, from Cape Branco to Cape São Tomé, Rio de Janeiro, and southern, from Cape São Tomé to Chuí Stream. The northern climate pattern is dominated by the Intertopical Convergence Zone, a belt of clouds shaped in an east-west direction by trade winds. It moves south of the Equator from Janury to April, although it may rapidly change its position, and brings convective rainfall, often in the form of storms. In some years it stays further north, causing drought in Northeastern Brazil and lower temperatures in the southern tropical Atlantic. The inverse happens when it stays further south.[169]

The central region is more seasonal. Easterly and northeasterly trade winds carry moisture from the coast and become colder and stronger in winter, from June to August, due to the South Atlantic High. In this period, precipitation increases between Cape Branco and Salvador and lowers to the south. Easterly waves and, from May to October, cold fronts cause rainfall, and in the latter case, rough seas and lower temperatures.[170]

The southern region is ruled by two phenomena, the South Atlantic Convergence Zone (SACZ) and extratropical cyclones. The SACZ is a northwest-southeast axis of clouds most common in summer, south of Bahia's coast, causing multiple days of bad weather. Extratropical cyclones may occur on a weekly basis in winter and are followed by cold fronts. They come from the south of the continent in a northeasterly direction. causing low temperatures, rainfall and rough seas. Wind speeds may exceed 60 km/h in trajectories parallel to the coast, occasionally sinking small fishing boats. Cold air masses linger in their aftermath, some of which are dry, having crossed the Andes, while others come from the Weddell Sea and are humid, but not as cold.[171]

Brazil's oceanic islands have maritime-influenced tropical climates. Trindade has an average annual temperature of 25 °C[172] and a dry season from January to March.[173] Fernando de Noronha has an average annual temperature of 27 °C, with a dry season from August to February.[174]

Oceanographic and meteorological data are traditionally collected by ships, coastal stations and drifting or stationary buoys, which is labor-intensive to repeatedly monitor over large areas and time periods, but can be eased by satellites. Public investment into these activities is organized since 1995 under the Pilot Program for the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS/Brasil), which includes the National Buoys Program and the Pilot Research Moored Array in the Tropical Atlantic (Pirata), a joint American-French-Brazilian program which contributes to climate monitoring in Northern and Northeastern Brazil.[175]

Marine life

Brazil's marine ecosystem is vast and hydrologically and topographically complex, spanning a wide range of habitats and high levels of endemism.[176][177] 31.8% of the coast's length can be classified into bays and estuaries, 27.6% as beaches and rocky shores, 18% as lagoons and coastal marshes, 13.6% as mangrove forests and 9% as dunes and cliffs.[178] About 3,000 km or a third of the coast has reefs in the continental shelf: coral reefs from 0° 52' N to 19° S and rocky reefs from 20° to 28° S.[179] At greater depths, sedimented slopes, submarine canyons, reef-forming and solitary corals, methane seeps and pockmarks, seamounts and guyots have distinct benthic communities.[180]

A 2011 literature review counted 9,103 marine species in the Brazilian coast, of which 8,878 were animals: 1,966 crustaceans, 1,833 molluscs, 1,294 vertebrates (fish), 987 annelids, 535 cnidarians, 400 sponges, 308 miscellaneous invertebrates, 254 echinoderms, 178 miscellaneous vertebrates, 133 bryozoans, 70 tunicates and 45 flatworms. In other kingdoms, two species were found among bacteria, 488 rhodophytes, 201 chlorophytes and 14 angiosperms among plants and 49 dinoflagellates and 15 foraminiferans among protists.[181] Real numbers may be as high as 13 thousand.[182] 66 invasive species have been accounted for.[183]

Although the number of species is high, each has a relatively small biomass.[7] The two prevailing currents, Brazil and North Brazil, are poor in nutrient salts in the euphotic layer, where photosynthesis and biomass production take place at the lowest trophic level,[159] and have a deep thermocline, which restrains bottom-to-surface nutrient flow.[184] Greater levels of biomass may be found in the Falkland Current, which has a higher concentration of nutrient salts; upwelling zones such as Cape Frio; closer to shore, where shallow waters, river discharge, wind and tides allow turbulence to enrich seawater;[159] and stretches of the Northern coast under the influence of the Amazon River's nutrient-rich fresh water.[168]

In nutrient poor-waters, picoplankton are the chief primary producers. Upwelling zones have larger species of phytoplankton and greater populations of pelagic fish. Pelagic community transfer organic matter to benthic communities, of which there are two geographical groups: thee northern, southeastern and southern coasts have flat bottoms of sand, mud and clay, whereas the eastern and northeastern coasts have irregular, rocky bottoms formed by calcareous algae.[185] Seabird diversity is relatively low (around 130 species). Rocas Atoll and other areas are breeding grounds for Northern Hemisphere birds, from September to May, and southern birds from May to August.[186]

Human activity

The "Blue Amazon's" human dimension is not as complex as the "Green Amazon's", as seafarers and oil rig workers are its only inhabitants.[187] On the other hand, 26.6% of the Brazilian population or 50 million inhabitants lived in the coastal zone's 450 thousand km2 as of the 2010 census,[188] a demographic density up to five times the national average.[189] This population is concentrated in a few urban centers, leaving other areas of the coast with a low density of occupation.[190] 13 state capitals are coastal.[189] Many coastal resources have concurrent and competing uses[191] and are thus a stage for social and environmental conflicts stemming from contradictions between environmental conservation, economic development and public, private, local and global interests.[192]

Interests as diverse as those of the ministries of Justice and Public Security, Defense, Foreign Affairs, Economy, Infrastructure, Agriculture and Livestock, Education, Citizenship, Technology and Innovation, Environment, Tourism and Regional Development are represented in the Interministerial Commission for Marine Resources (Comissão Interministerial para os Recursos do Mar, CIRM).[193] This body coordinates the state's strategic programs in the sector, such as LEPLAC, as outlined in the National Marine Resources Policy and the four-year Sectoral Plans for Marine Resources. The CIRM is coordinated by the Commander of the Navy, who is represented in the commission by an officer who also heads the Secretariat (SECIRM), a supporting organ which maintains contact with federal ministries, state governments, the scientific community and private entities.[194][195]

Research

The Brazilian state invests in several research programs in the South Atlantic to shore up its continental shelf expansion proposals, ensure national presence in oceanic islands and understand the area's biodiversity and natural resources.[196] National oceanography has succeeded in surveys of the continental shelf's geology and the EEZ's living resources, engineering projects and participation in international research programs, but the number of researches and availability of equipment and vessels are not enough for the breadth of the field.[197]

Oceanic science, technology and innovation in the country is mostly financed by public entities, with notable exceptions of companies such as Chevron, Equinor, Shell and Vale.[198] 65 higher education institutions offered 1,840 annual positions in courses in Marine Sciences in 2022.[199] Both the Navy and civilian institutions operate oceanographic research vessels.[200] A national institute of the sea comparable to the role played by the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária andFundação Oswaldo Cruz in other areas,[201] did not exist until the foundation of the National Oceanic Research Institute (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Oceânicas, Inpo). Initially staffed with only 17 officials and a yearly budget of R$ 10 million, it is a small organization conceived to aggregate research data and direct strategic projects.[202]

According to the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, out of 370 thousand papers on marine science published globally in 2010–2014, Brazilian authors were on 13 thousand. In four categories, "functions and processes of marine ecosystems", "ocean health", "blue growth" and "human health and well-being", the percentage of papers in Brazil's total scientific output is higher than the international average, and the country is deemed specialized in these areas. The category "marine data and oceanic observation" is at the global average and "oceans and climate", "oceanic technology" and "oceanic crust and marine geological risks" were below average.[201]

Economy

Brazilian jurisdictional waters directly participate in the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in six sectors: services (particularly tourism), energy, manufacturing, defense, fishing and transport.[203] Furthermore, the sea hosts critical communications infrastructure, submarine cables through which the Brazilian Internet receives 98% of its data.[204][117] Indirect economic contributions are much greater and may be difficult to measure: for instance, coastal sites boost value in the real estate sector. Specialists deem the maritime economy to still have idle potential, particularly in the "blue GDP" or blue economy,[203] a socially- and environmentally-minded economic frontier.[205]

A "maritime sector" does not exist in chief economic indexes such as the GDP and many activities are counted as part of other sectors, such as agriculture.[206] There is no official and systematic methodology for its calculation.[10] The first scientific study to account for the sector[207] produced estimates for 2015: the maritime economy produced R$ 1.1 trillion or 18.93% of the national GDP and employed 19,829,439 workers. "Maritime-adjacent" sectors[h] were responsible for 16.26% of the GDP and 17,745,279 jobs, mostly in the tertiary sector. Activities directly conducted offshore, or whose products offshore, represented 2.67% of the GDP and 2,084,160 jobs.[i]

In this estimate, the tourism-centered service sector is the chief activity in Brazil's maritime economy, rather than traditionally maritime sectors such as oil and gas, fishing and aquaculture.[211] When properly accounted for, the sector is comparable in size to agribusiness.[206] Comparisons with estimates in other countries may be misleading, as their methodologies are different,[212] but the value estimated for the economy directly connected to the sea is consistent with a 2013 United States estimate of 2.2% of national GDP.[213] In 2020 the CIRM tasked a research team with the definition of a measuring methodology so that in the future, official numbers can be published through the Institute of Geography and Statistics.[207]

Trade

Coastal cities have in the sea a natural trade route between themselves and with other continents, one that is cost-effective for large volumes of cargo and long distances.[214] Brazilian ports moved 1.151 billion tons of cargo in 2020[215] and employed 43,205 registered workers in 2021.[216] The busiest ports were Santos, Paranaguá and Itaguaí,[215] but Northern and Northeastern ports are on the rise as export terminals for Center-Western agricultural production.[217]

Maritime transport is the primary mode of Brazilian international trade, shipping 98.6% of exports by weight and 88.9% by value in 2021 and 95% of the weight and 74% of the value of imports.[215] In contrast, waterways were used in only 15% of internal trade in 2015, 10% in coastal shipping and 5% inland. The sector has declined since 1950, when 32.4% of domestic transport demand was provided by ship.[218]

Transport between coastal hubs was historically provided almost exclusively by coastal shipping, but since the 1950s, developmental policies have prioritized land transport and the automobile industry. In the present, highways are the primary mode of transport.[218] Coastal shipping has idle potential,[219] and the sector's representatives emphasize its predictability, multimodality and lower risks of damage, theft and environmental accidents.[220] However, companies interested in coastal shipping face logistical difficulties in modal integration, insufficient line frequency and high costs, which are a result of the fleet's high occupancy rates.[221]

The Brazilian Merchant Marine employed 26,631 mariners, 887 ships and 5.522 million in deadweight tonnage in 2023.[222] It is well-represented on internal shipping, in which it provided for 92% of container transport, 59.1% of general cargo, 24.3% of dry bulk cargo and 4.1% of wet bulk cargo in 2021.[223] On international trade, the Brazilian flag can hardly be seen, with a few exceptions such as shipping to other Mercosul countries or oil exports.[224] In 2008, Brazilian companies were responsible for around 10% of the international freight market, mostly by using chartered foreign vessels.[225] In 2005, only 4% of freight fees from external trade were paid to Brazilian companies.[226]

Shipbuilding

Brazil's naval industry is historically concentrated in the state of Rio de Janeiro. 26 shipyards were in operation in 2010, of which 15 were in Rio. 152 projects were under construction in 2016, mostly barges and towboats (82 units), followed by oil tankers, offshore support vessels, tugboats, oil platforms, submarines and gas tankers.[227] The industry is labor-intensive and each direct job may indirectly create another five.[228] Shipyards employed 21 thousand workers in 2019, a major drop from the 82 thousand in 2014, but the sector was recovering.[229]

At the peak of shipbuilding, ships flying the national flag provided 17.6% of international freight in 1974. Production began to decline in the 1980s and growth was only regained in the 21st century, driven by the oil industry's demand.[230] National-flagged vessels couldn't compete after deregulation and the lifting of protectionist policies, and local shipbuilding costs remained higher than in other countries with greater labor and energy prices.[231][232]

Tourism

Nautical tourism provided for R$ 12.6 billion of Brazil's 2023 GDP, only accounting for travel and sports in speedboats, sailboats, yatches, jets and similar craft. The boat sector created 150 thousand direct and indirect jobs. The cruise ship sector added a further R$ 5 billion and 80 thousand jobs in the 2023/2024 season.[233] More broadly, coastal tourism also includes beaches, bathing resorts and diving) and their infrastructure: hotels, food, recreation, sporting equipment and marinas.[215] Brazilian attractions in this sector are the vast coastline and internal waters, its climate and its scenery, with tropical and subtropical white sand beaches and, further south, coastal mountains.[234] A deficit of cruise ship vacancies in the 2023/2024 season suggests an untapped potential, but insufficient docks are a major shortcoming.[233]

Fuel

Petroleum reserves in the continental shelf in general and the pre-salt layer in particular are key to Brazilian interest in the area.[235] Most national oil and natural gas reserves lie offshore[236] — 95.1% of 2023 production in barrels of oil equivalent.[237] This sector is the most technology-intensive activity in the Brazilian marine economy[203] and corresponded to 15% of 2022's industrial GDP, 7% from extraction and 8% from the derivatives market.[238]

Average daily production stood at 3.402 million barrels of crude oil and 150 million m3 of natural gas in 2023,[239] with proven reserves of 15.894 billion barrels of oil and 517 billion m3 of gas.[240] These oil reserves were the world's 14th largest in 2018.[6] Brazil is nominally self-sufficient in oil, with production outpacing consumption, but it still imports crude oil and derivatives such as gasoline and diesel fuel.[5]

The South Atlantic's geological evolution favored oil and gas accumulation in sedimentary basins at the continental margins.[241] In the early breakup of South America and Africa, organic matter-rich sediments were deposited in rift valleys. A warm, high-evaporation climate covered them in salt, forming a pre-salt layer of oil and natural gas.[242][243] Much of this layer is at the 200 nmi line.[244] The most important sedimentary basin is the Santos Basin, which produced 74.08% of oil and 75.34% of gas in 2023. The Campos Basin comes second in both items.[245] The first offshore oil well was drilled in 1968, and the major pre-salt reserves were found in the 2000s.[246] Since then, production has risen continually,[247] exceeding post-salt output in 2017.[248]

Coal deposits were found near Santa Terezinha Beach, in Rio Grande do Sul, at depths of 700–800 m.[249] Gas hydrates — methane molecules trapped in ice crystals within sediment — were found in the Amazon and Rio Grande fans, but information is incomplete for the rest of the country. They are a potential alternative to oil and natural gas, but their extraction, storage and employment are still technologically difficult.[250][251]

Minerals

Beyond oil and gas, the South Atlantic's seabed and subsoil are a new frontier of undersea mining. Knowledge of its mineral potential is still incomplete, but interest tends to grow as continental reserves are exhausted and marine exploration technology moves forward.[252] The Brazilian continental shelf contains deposits of aggregates, heavy mineral sands, phosphorites, evaporites and sulphur.[253][254] Greater depths and distances from the shore have been prospected for cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts, polymetallic sulfides and polymetallic nodules. Most are in the "Area" — the stretch of seabed under international jurisdiction — with the notable exceptions of the areas around Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Trindade and Martim Vaz and the Rio Grande Rise.[255] In most cases, technologies for their exploitation and use are still unavailable.[256]

Aggregates occur in two categories: siliciclastic, composed of sand and gravel, and bioclastic, which are rich in calcium carbonate and composed of sand, gravel, rhodoliths and carbonate concretions. Siliciclastic aggregates are extracted at depths of up to 30 m, with an estimated potential of billions of cubic meters through the coast. They can be used in the cement, glass and steel industries, in construction and in the reconstruction of eroded shores. Bioclastic aggregates occur from the Pará River to Cape Frio and can be used in agriculture, water filters, cosmetics, dietary supplements, bone implants, construction, the steel industry and water treatment.[257]

Phosphorites are correlated with upwelling zones and are therefore uncommon in the Brazilian continental margin. However, they have been found in the Ceará Plateau at a 400 m depth, the Pernambuco Plateau at 700–1,250 m, the Florianópolis Terrace at 200–600 m, the Rio Grande Terrace at 200–800 m and the Rio Grande Rise at 700–1,500 m. They can be used as fertilizer and industrial phosphorus sources, and some deposits have significant concentrations of iron, titanium and rare earth metals.[258][259]

Heavy mineral placer deposits are found in both emerged and submerged portions of the coast, from Pará to Rio Grande do Sul. Zirconite, titanium-rich rutile and ilmenite, cerium- and thorium-rich monazite have seen industrial-scale extraction in the past or the present. In the submerged portion, extraction at depths of 40 to 100 m is viable but not yet undertaken. The mouth of the Jequitinhonha and Pardo-Salobro rivers in Bahia may contain diamond deposits.[260]

Mineral salt evaporites — anhydrous salts, gypsum, halite, potassium and manganese — overlay the pre-salt layer from the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin to the Santos Basin. As of 2005, the Sergipe-Alagoas Basin was the only potassium chloride production site in the country, with estimated reserves of 13.5 million tons. Deposits from Abrolhos to Mucuri, in Bahia, and Barra Nova, in Espírito Santo, are particularly promising for their minimal depths and distances from the shore. In Abrolhos, sulfide-covered saline domes have been found at depths of 20 to 30 m.[261][262]

Iron- and manganese-rich polymetallic nodules have been identified in the Pernambuco Plateau at depths of 1,750 to 2,200 m, in the Vema Channel and in the Vitória-Trindade Ridge. Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts occur in the Pernambuco Plateau at depths of 1,000 to 3,000 m and in the Rio Grande Rise. Hydrothermal deposits of polymetallic sulfides and associated metalliferous sediment likely exist around the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago. The Brazilian Geological Service signed a contract in 2015 with the International Seabed Authority to survey the Rio Grande Rise, which was at the time considered an area under international jurisdiction.[263][264] Once it was claimed as part of the extended continental shelf, the contract was ended in 2021.[265]

Renewable energy

The Brazilian coast has an untapped potential in renewable energy generation from tidal, wave and offshore wind power. Total tidal and wave generation potential was estimated at 114 GW in 2022. Viable site for tidal power generation are in the Northern region and Maranhão, while wave power is possible in the remaining coastal states.[266] Offshore wind power potential was estimated in 2024 at 480 GW over fixed foundations (at maximum depths of 70 m) and 748 with floating wind turbines. Major urban centers such as Fortaleza, Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre are close to the main potential wind power areas, with the greatest potential in the South. However, initial costs would be high and a significant scale of production would only be achieved with significant investments in the transmission network, port infrastructure and manufacturing capacity.[267] For comparison, Brazil's electrical grid had 200 GW of centralized power in 2024, primarily sourced from hydroelectric power.[268]

Fishing

Brazil historically provides little more than 0.5% of global marine fishing output.[269] The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization accounted for a national fishing production of 758 thousand tons in 2022, out of a global total of 91.029 million. Over 30% of captures take place in rivers and lakes. Brazil also produced 738 thousand tons from aquaculture out of a global total of 94.413 million.[270][271] Export-focused industrial fishing developed in the country since the 1960s, driven by a mistaken belief that fish stocks would be endless.[272] The vast oceanic area under national jurisdiction does not by itself make the country a fishing power, as already mentioned oceanographic conditions do not produce a large biomass of fish.[7]

Fish stocks were comprehensively surveyed by the Program for Evaluation of the Sustainable Potential of Living Resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone of Brazil (Programa de Avaliação do Potencial Sustentável de Recursos Vivos na Zona Econômica Exclusiva do Brasil, ReviZEE), a decentralized, multidisciplinary effort undertaken in 1996–2005.[273][274] As of its conclusion, 69% of marine fish output consisted of eight families: Quando de sua conclusão, 69% da pesca marinha consistia em oito famílias: pescadas and corvinas (Sciaenidae), sardines (Clupeidae), tunas and related fish (Scombridae), shrimp (Penaeidae), catfish (Ariidae) , tainhas (Mugilidae), arabaianas, xaréus, xareletes, garajubas and other fish of the Carangidae family and red fishes of the Lutjanidae family.[275] Most species targeted by coastal and continental fisheries were over-exploited and there was no perspective of increased production. Oceanic fisheries had greater potential, but even then, stocks were nearing the limits of sustainable exploitation.[276] Even at deeper waters inaccessible to traditional fleets, stocks have limited potential.[256] The greatest long-term potential for growth lies in aquaculture,[270] including mariculture in the coast's many bays and bights.[277]

Fishing and aquaculture provide little more than 0.5% of national GDP, though they are relevant at the local level, creating 3.5 million direct and indirect jobs. Most of them work in artisanal shipping; out of an estimated fleet of 21,732 vessels in 2019, most had less than 12 meters in length and only a third were motorized. Industrial fishing is concentrated in the South and Southeast.[270] Fish are not central to the Brazilian diet: annual per capita consumption stood at 9.5 kg in 2020, below the global average of 20 kg.[270] Even then, production does not meed demand in 2022 Brazil was among the world's 11 largest fish importers.[278]

Biotechnology

Besides fishing, another category of living resources is biotechnology, which takes advantage of molecules and genes from marine microorganisms. In the South Atlantic, research in this area focuses on hydrolytic enyzmes and bioremediation. The Brazilian state promotes a prospection program, Biomar, since 2005. This activity has next to no environmental impacts, but the industrialization of marine biotechnological products was still distant as of 2020.[279]

Environmental policy

Brazilian marine ecosystems are under pressure from industrial fishing, navigation, port and land pollution, coastal development, mining, oil and gas extraction, invasive species and climate change.[280] Industrial, mining, agriculture, pharmaceutical, sanitary and other residues drain into the sea from the continent. A particularly serious case was the Mariana dam disaster, which led to mining residues with a high concentration of iron, aluminum, manganese, arsenic, mercury and other metals crossing over 600 km through the Doce River until meeting the sea. Oil spills are the most visible type of pollution,[281] of which the largest case took place in the Northeastern coast in 2019.[282] Global ocean acidification may impede biogenic calficication in Espírito Santo and the Abrolhos Bank and dissolve existing shells and skeletons, releasing carbon dioxide.[182] In the South Atlantic, increasing seawater surface temperatures will tend to weaken the Falkland Current, displacing the Brazil-Falkland Confluence to the south.[283]

27.6% of the territorial sea and 26.4% of the EEZ, or 26.5% of these areas in total, were protected under 190 conservation units in 2021. Coastal areas had a further 549 units.[8] Until 2020, when environmental protection areas were decreed in the archipelagos of Saint Peter and Saint Paul and Trindade and Martim Vaz, conservation unit coverage in the EEZ did not exceed 1.5%.[284] This measure allowed Brazil to announce its full implementation of Aichi Target 11, the protection of at least 10% of coastal and marine areas, which it had committed itself to fulfill in 2010, as a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity.[285] However, full (no-take) protection coverage stood at only 2.5%. The Ministry of the Environment had as its target to extend this number to 10% in the following 15 years.[284]

Unprotected areas that could be given priority include reefs at the edge of the Amazonic continental shelf, shallow waters of the North Brazilian Chain, the southern part of the Abrolhos Bank and, in the South, deep-water coral reefs, rhodolith beds and mobile bottom benthic communities. The most serious overlap between risk factors and biodiversity is at areas in the Southeast and southern Bahia, to a total of 83 thousand km2. This conclusion was published in the journal Diversity and Distributions in 2021, based on the distribution of 143 animal species with critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable conservation status. Its authors contend that the criteria for existing areas have been more opportunistic and political than biologica.[286][284] The archipelagos of Saint Peter and Saint Paul and Trindade and Martim Vaz are remote areas and their conservation harms few economic interests, unlike the coast.[9]

Security

The "Blue Amazon's" limits are imaginary lines over the sea and only physically exist insofar as they are patrolled by Brazilian ships.[126] Jurisdictional waters are a border region and as such, must be monitored and if needed, denied access to external actors. This burden falls on the Armed Forces and particularly the Navy,[287] in its "dual" nature, simultaneously tasked with police and war operations. There is no independent coast guard.[288] In formal recognition of this role, the Navy Command is rewarded with some of the royalties of offshore oil extraction. The Brazilian Air Force aids the Navy's activities with its patrol aircraft.[289] Brazil has further responsibilities of maritime search and rescue from the 7th parallel north to the 35th parallel south, as far east as the 10th meridian west.[290]

The Navy's "coast guard" dimension is embodied in its Naval Districts, to which a considerable number of patrol vessels are assigned.[291] The Navy's commander is the Brazilian Maritime Authority and as such is responsible for implementing and overseeing laws and regulations on the sea and interior waters,[292] if needed by seizing foreign vessels which conduct unauthorized activities in any of the BJW's maritime zones and refer them to appropriate authorities.[293] Furthermore, its secondary roles include directing the Merchant Marine and related activities inasmuch as they are relevant to national defense.[294] Merchant Marine officers are exclusively trained by the Navy,[295] serve as its unpaid reserve and may be mobilized in wartime.[296]

In its warmaking dimension, the Navy is tasked with deterring foreign powers[297] and, should war break out, to deny them use of the sea, control maritime areas and project power over land. Its priorities are the coastal strip between Santos and Vitória, the Amazon Delta, archipelagos, oceanic islands, oil rigs and naval and port installations.[298] Beyond the BJW, the Atlantic Ocean between the 16th parallel north and the shores of Antarctica is designated as Brazil's "strategic neighborhood".[299]

In defense of its interests in the South Atlantic, Brazil has pursued a two-pronged effort of military buildup and the development of closer ties with other states in the region.[300][301] In the latter, the Navy has taken part of joint naval exercises, technical advisory and arms transfers to African states, while the diplomatic corps attempted to revive the South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone (ZOPACAS).[302] In the former, the "defense of the Blue Amazon" is the motto for new investments in naval ships.[303] In the 2000s, economic growth, newly-discovered oil and gas reserves and newly-published defense policy documents, such as the 2008 National Defense Strategy,[301] were the backdrop to the ambitious Navy Articulation and Equipment Plan (Plano de Articulação e Equipamento da Marinha, PAEMB), which promised a fleet worthy of an international power, including two 50 thousand-ton aircraft carriers and six nuclear submarines, until the 2030s.[13] This force would have been supported by the Blue Amazon Management System (Sistema de Gerenciamento da Amazônia Azul, SisGAAz), a network of satellites, radars and underwater sensors to monitor the BJW.[304]

The PAEMB fell short of budgetary possibilities and was dropped in its original format.[13] As of 2016, the SisGAAz no longer had an official conclusion date.[305] From 2000 to 2022 the fleet decommissioned two aircraft carriers, a tanker, three amphibious assault ships, three submarines, three minesweepers and eleven escort ships. In the same period it commissioned a helicopter carrier, an amphibious assault ship, an escort and two submarines. Four escorts and three submarines were under construction, but a further 40% of the fleet was to be decommissioned until 2028.[12] In 20223 most of the surface fleet was nearing 40 years of use and faced block obsolescence. The Seaforth World Naval Review judged that the Navy has managed to transfer the concept of a "Blue Amazon" to the population, but "unless the political will can be found to increase its resources, the Brazilian Navy will be left with a capacity far below its responsibilities".[306] Tecnologia & Defesa magazine complained of a "lack of priority given by most politicians to the defense agenda" and a "weak maritime mentality in the public at large".[12]

Perceived threats

A well-defined enemy was the missing piece which prevented the Blue Amazon's public relations campaign from fully convincing the public, in the opinion of journalist Roberto Lopes. Conventional threats seemed distant in the post-Cold War environment.[69] The South Atlantic is a "traditionally peaceful zone", in the words of the former Defense and Foreign Affairs minister Celso Amorim.[307] Brazil has cordial relations with its neighbors on land.[308] Under American hegemony, a regional war is unlikely and Brazil has assumed the luxury of maintaining a low military readiness.[309][310]

The Brazilian government has expressed convern over non-traditional threats such as piracy, terrorism, drug, arms and human trafficking, environmental offenses, illegal fishing, biopiracy and other transnational crimes. Some are already present on the West African coast and may at some point reach Brazil's maritime routes.[311][312][313] The Navy frequently encounters illegal waste disposal and other environmental crimes.[314] Incidents with illegal fishing vessels are also common on international waters close to Brazil. In Argentina, such cases have led to the boarding, seizure, pursuit and even sinking of these vessels.[315] "Ghost ships" which deliberately conceal their position and movements may be used for aforementioned crimes as well as unauthorized geological and biological surveys and espionage and data theft from submarine cables.[316]

Local military thinkers do not reject a possible return of conventional threats — powerful states driven by the depletion of natural resources to question national sovereignty and jurisdiction over the BJW.[313] Nationalist and military sectors are particularly concerned about the continental shelf's oil and natural gas reserves.[235] The National Defense Strategy has made explicit Brazil's opposition to any extraregional military presence in the South Atlantic and the projection of conflicts and rivalries alien to the region. This extraregional presence already exists: the United States with its Fourth Fleet, the United Kingdom with Ascenscion Island, Saint Helena, Tristan da Cunha and the Falkland Islands and France with French Guiana.[302] Brazilian and Argentine strategic thinkers have studied those three powers as potential enemies.[317] The Fourth Fleet's reactivation in 2008, in this line of thought, was tied to Brazil's pre-salt oil and gas discoveries.[318] Besides the three North Atlantic Western powers, China's naval influence has grown in African states.[12]