Boxer Protocol

| China and the 11 countries' final agreement on compensation for the 1900 turmoil | |

|---|---|

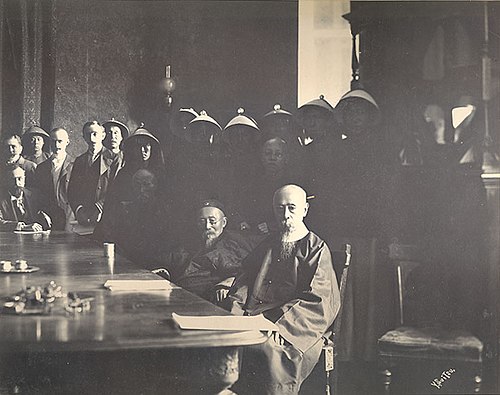

Signature page of representatives of various countries on the Boxer Protocol settlement | |

| Type | Diplomatic protocol, unequal treaty |

| Signed | September 7, 1901 (July 25th, Year Guangxu 27) (Chinese: 光緒) |

| Location | Spanish Embassy in Beijing |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | National Palace Museum, Taipei City |

| Language | Chinese, French (The agreement is based on French) |

| Full text | |

| Boxer Protocol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 1. 辛丑條約 2. 辛丑各國和約 3. 北京議定書 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 1. 辛丑条约 2. 辛丑各国和约 3. 北京议定书 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 1. Xinchou (year 1901) treaty 2. Xinchou (year 1901) all-nation peace treaty 3. Beijing protocol | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Boxer Protocol was a diplomatic protocol[1] signed in China's capital Beijing on September 7, 1901, between the Qing Empire of China and the Eight-Nation Alliance that had provided military forces (including France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Japan, Russia, and the United States) as well as Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands, after China's defeat in the intervention to put down the Boxer Rebellion. The protocol is regarded as one of China's unequal treaties.

Name

The 1901 protocol is commonly known as the Boxer Protocol or Peace Agreement between the Great Powers and China in English. It is known as the Xinchou Treaty[2]: 16 or Beijing protocol in Chinese, where "Xinchou" refers to the year (1901) of signature under the sexagenary cycle system. The full English name of the protocol is Austria-Hungary, Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Russia, Spain, United States and China – Final Protocol for the Settlement of the Disturbances of 1900, reflecting its nature as a diplomatic protocol rather than a peace treaty at the time of signature.

Negotiations during the Boxer Rebellion

The Qing dynasty was by no means completely defeated when the Allies took control of the capital Beijing. The Allies had to temper the demands they sent in a message to Xi'an to get the Empress Dowager Cixi to agree with them; for instance, China did not have to give up any land. Many of the Dowager Empress' advisers in the Imperial Court insisted that the war continue against the foreigners, arguing that China could defeat them since it was the disloyal and traitorous people within China who allowed Beijing and Tianjin to be captured by the Allies, and the interior of China was impenetrable. The Dowager was practical and decided that the terms were generous enough for her to acquiesce and stop the war when she was assured of her continued reign.[3]

Signatories

The Boxer Protocol was signed on September 7, 1901, in the Spanish Legation in Beijing. Signatories included:[4]

Foreign powers

Kingdom of Spain, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Bernardo J. de Cólogan y Cólogan, the Doyen of the Diplomatic Corps and the eldest diplomat of the Foreign Compound in Beijing.[4]

Kingdom of Spain, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Bernardo J. de Cólogan y Cólogan, the Doyen of the Diplomatic Corps and the eldest diplomat of the Foreign Compound in Beijing.[4] United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Ernest Mason Satow.

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Ernest Mason Satow. Russian Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Mikhail Nikolayevich von Giers.

Russian Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Mikhail Nikolayevich von Giers. Empire of Japan, represented by the Minister for Foreign Affairs Komura Jutarō.

Empire of Japan, represented by the Minister for Foreign Affairs Komura Jutarō. French Republic, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Paul Beau.

French Republic, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Paul Beau. United States of America, represented by the Special envoy William Woodville Rockhill.

United States of America, represented by the Special envoy William Woodville Rockhill. German Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein.

German Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein. Austro-Hungarian Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Baron Moritz Czikann von Wahlborn.

Austro-Hungarian Empire, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Baron Moritz Czikann von Wahlborn. Kingdom of Italy, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Giuseppe Salvago Raggi.

Kingdom of Italy, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Giuseppe Salvago Raggi. Kingdom of Belgium, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Maurice Joostens.

Kingdom of Belgium, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Maurice Joostens. Kingdom of the Netherlands, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Fridolin Marinus Knobel.

Kingdom of the Netherlands, represented by the Minister plenipotentiary Fridolin Marinus Knobel.

and

Qing Empire, represented by:

Qing Empire, represented by:

- Li Hongzhang, Earl of the First Rank Su-i, Tutor of the Heir Apparent, Grand Secretary of the Wen Hua Tien, Minister of Commerce, Superintendent of the Northern Ports, and Viceroy of Zhili.

- Yikuang, Prince Qing, first Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet.

|

|

The clauses

Italy,

Italy,  France,

France,  Germany,

Germany,  Russia and

Russia and  Japan, 1901.

Japan, 1901.450 million taels of fine silver (around 18,000 tonnes, worth approx. US$333 million or £67 million at the exchange rates of the time) were to be paid as indemnity over 39 years to the eight nations involved.[5]

The Chinese paid the indemnity in gold on a rising scale with a 4% interest charge until the debt was amortized on December 31, 1940. After 39 years, the amount was almost 1 billion taels (precisely 982,238,150),[5] or ≈1,180,000,000 troy ounces (37,000 tonnes) at 1.2 ozt/tael.

The sum was to be distributed as follows: Russia 28.97%, Germany 20.02%, France 15.75%, Britain 11.25%, Japan 7.73%, United States 7.32%, Italy 7.32%, Belgium 1.89%, Austria-Hungary 0.89%, Netherlands 0.17%, Spain 0.03%, Portugal 0.02%, Sweden and Norway 0.01%.[6]

Other clauses included

- To prohibit the importation of arms and ammunition, as well as materials for the production of arms or ammunition, for two years, extensible further two years as the Powers saw necessary.

- The destruction of Taku Forts.[7]

- Legation Quarters occupied by the Powers shall be considered a special area reserved for their use under the exclusive control, in which Chinese shall not have the right to reside and may be defensible. China recognized the right of each Power to maintain a permanent guard in the said Quarters for the defense of its Legation.

- Boxers and government officials were to be punished for crimes or attempted crimes against foreign governments or their nationals. Many were sentenced to execution, deported to Xinjiang, imprisoned for life, forced to commit suicide, or suffered posthumous degradation.

- The "Office in Charge of Affairs of All Nations" (Zongli Yamen) was replaced with a Foreign Office, which ranked above the other six boards in the government.

- The Chinese government was to prohibit forever, under pain of death, membership in any anti-foreign society, civil service examinations were to be suspended for five years in all areas where foreigners were massacred or subjected to cruel treatment, and provincial and local officials would personally be held responsible for any new anti-foreign incidents.

- The emperor of China was to convey his regrets to the German emperor for the assassination of Baron von Ketteler.

- The emperor of China was to appoint Na't'ung to be his envoy extraordinary and direct him to also convey to the emperor of Japan his expression of regrets and that of his government at the assassination of Mr. Sugiyama.

- The Chinese government would have to erect on the spot of the assassination of Baron von Ketteler a commemorative arch inscribed in Latin, German, and Chinese.

- Concede the right to the Powers to station troops in the following places:[8]

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Transliterated names from early text using a system that pre-dates Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 黃村 | 黄村 | Huangcun | Huang-tsun |

| 郎坊(廊坊) | 郎坊(廊坊) | Langfang | Lang-fang |

| 楊村 | 杨村 | Yangcun | Yang-tsun |

| 天津 | 天津 | Tianjin | Tien-tsin |

| 軍糧城 | 军粮城 | Junliangcheng | Chun-liang-Cheng |

| 塘沽 | 塘沽 | Tanggu | Tong-ku |

| 蘆臺 | 芦台 | Lutai | Lu-tai |

| 唐山 | 唐山 | Tangshan | Tong-shan |

| 灤州 | 滦州 | Luanzhou | Lan-chou |

| 昌黎 | 昌黎 | Changli | Chang-li |

| 秦皇島 | 秦皇岛 | Qinhuangdao | Chin-wang Tao |

| 山海關 | 山海关 | Shanhaiguan | Shan-hai Kuan |

Hoax demands

The French Catholic vicar apostolic, Msgr. Alfons Bermyn, wanted foreign troops garrisoned in Inner Mongolia, but the governor refused. Bermyn resorted to lies and falsely petitioned the Manchu Enming to send troops to Hetao, where Prince Duan's Mongol troops and General Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops allegedly threatened Catholics. It turned out that Bermyn had created the incident as a hoax.[9][10] One of the false reports claimed that Dong Fuxiang wiped out Belgian missionaries in Mongolia and was going to massacre Catholics in Taiyuan.[11][12]

Demands rejected by China

The Qing did not capitulate to all foreign demands. The Manchu Governor Yuxian was executed, but the Imperial court refused to execute the Chinese General Dong Fuxiang, although both were anti-foreign and had been accused of encouraging the killing of foreigners during the rebellion.[13] Instead, General Dong Fuxiang lived a life of luxury and power in "exile" in his home province of Gansu.[14][15]

In addition to sparing Dong Fuxiang, the Qing refused to exile the Boxer supporter Prince Zaiyi to Xinjiang, as the foreigners demanded. Instead, he moved to Alashan, west of Ningxia, and lived in the residence of the local Mongol prince. He then moved to Ningxia during the Xinhai Revolution when the Muslims took control of Ningxia, and finally moved to Xinjiang with Sheng Yun.[16] Prince Duan "went no farther than Manchuria for exile, and was heard of there in 1908".[17]

Spending and remittance

On December 28, 1908, the United States remitted $11,961,121.76 of its share of the Indemnity to support the education of Chinese students in the United States and the construction of Tsinghua University in Beijing,[18] thanks to the efforts of the Chinese ambassador Liang Cheng.[19]

When China declared war on Germany and Austria in 1917, it suspended the combined German and Austrian share of the Boxer Indemnity, which totaled 20.91 percent. At the Paris Peace Conference, Beijing succeeded in completely revoking the German and Austrian shares of the Boxer Indemnity.[20]

The history surrounding Russia's share of the Boxer Indemnity is the most complex of all the nations involved. On December 2, 1918, the Bolsheviks issued an official decree abolishing Russia's share of the Indemnity (146). Upon the arrival of Lev Karakhan in Beijing during the fall of 1923, however, it became clear that the Soviet Union expected to retain control over how the Russian share was to be spent. Though Karakhan was initially hesitant to follow the United States' example of directing the funds toward education, he soon insisted in private that the Russian share had to be used for that purpose and, during February 1924, presented a proposal stating that the "Soviet portion of the Boxer Indemnity would be allocated to Chinese educational institutions."[21] On March 14, 1924, Karakhan completed a draft Sino-Soviet agreement stating, "The government of the USSR agrees to renounce the Russian portion of the Boxer Indemnity." Copies of these terms were published in the Chinese press, and the positive public reaction encouraged other countries to match the USSR's terms. On May 21, 1924, the U.S. Congress agreed to remit the final $6,137,552.90 of the American share to China. Ten days later, however, it became apparent that the USSR did not intend to carry through on its earlier promise of full renunciation. When the final Sino-Soviet agreement was announced, it specified that Russia's share would be used to promote education in China and that the Soviet government would retain control over how the money was to be used, an exact parallel to the U.S. remittance of 1908.[22]

On March 3, 1925, Great Britain completed arrangements to use its share of the Boxer Indemnity to support railway construction in China. On April 12, France asked that its indemnity be used to reopen a defunct Sino-French Bank. Italy signed an agreement on October 1 to spend its share on the construction of steel bridges. The Netherlands' share paid for harbor and land reclamation. The Netherlands also used its indemnity for the establishment of the Sinological Institute at Leiden University.[23] The Belgian funds were earmarked to be spent on railway material in Belgium. Finally, Japan's indemnity was transferred to develop aviation in China under Japanese oversight.[24] Once these countries' approximately 40 percent of the Boxer Indemnity was added to Germany's and Austria's combined 20.9 percent, the United States' 7.3 percent, and the Soviet Union's 29.0 percent share, the Beijing government had accounted for over 98 percent of the entire Boxer Indemnity. Hence, by 1927, Beijing had almost entirely revoked Boxer Indemnity payments abroad and successfully redirected the payments for use within China.[25]

See also

- China Relief Expedition

- Boxer Rebellion

- Mutual Protection of Southeast China

- Beijing Legation Quarter

- Imperial decree on events leading to the signing of Boxer Protocol

- China Consortium

References

- ^ Koon San Tan (2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. p. 445. ISBN 9789839541885.

- ^ Cheng, Wenting (2023). China in Global Governance of Intellectual Property: Implications for Global Distributive Justice. Palgrave Socio-Legal Studies series. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-031-24369-1.

- ^ Preston, Diana (2000). The Boxer Rebellion: the dramatic story of China's war on foreigners that shook the world in the summer of 1900. US: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 312. ISBN 9780802713612. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Cologan y Gonzalez-Massieu, Jorge (2008). "El papel de Espana en la Revolucion de los Boxers de 1900: Un capitulo olvidado en la historia de las relaciones diplomaticas". Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish). 205 (3). La Academia: 493. OCLC 423747062.

- ^ a b Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for Modern China (1st pbk. ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0393307808.

- ^ Ji, Zhaojin (March 2003). A History of Modern Shanghai Banking. M.E. Sharpe. p. 75. ISBN 9780765610027. OL 8054799M.

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415214773.

- ^ Pamphlets on the Chinese-Japanese War, 1939–1945. [Published 1937] Sino-Japanese Conflict, 1937–45. Digitized May 30, 2007. No ISBN.

- ^ Ann Heylen (2004). Chronique du Toumet-Ortos: looking through the lens of Joseph Van Oost, missionary in Inner Mongolia (1915–1921). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 203. ISBN 90-5867-418-5. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Patrick Taveirne (2004). Han-Mongol encounters and missionary endeavors: a history of Scheut in Ordos (Hetao) 1874–1911. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 539. ISBN 90-5867-365-0. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Edwards, E. H. (1903). Fire and sword in Shansi: the story of the martyrdom of foreigners and Chinese Christians. New York: Revell. p. 167. OL 13518958M.

- ^ Hart, Robert; Campbell, James Duncan (1975). Fairbank, John King; Bruner, Katherine Frost; Matheson, Elizabeth MacLeod (eds.). The I. G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868–1907. Harvard University Press. p. 1271. ISBN 0674443209. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Stephen G. Haw (2007). Beijing: a concise history. Routledge. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-415-39906-7. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis Herbert, eds. (1915). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics. Vol. 8. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. p. 894. OCLC 3065458.

- ^ M. Th. Houtsma, A. J. Wensinck (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936. Stanford Brill. p. 850. ISBN 90-04-09796-1. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Teichman, Eric (1921). Travels of a Consular Officer In North-West China. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 188. OCLC 2585746. OL 14046010M.

- ^ Clements, Paul Henry (1915). The Boxer Rebellion: A Political and Diplomatic Review. Columbia University. p. 201. OL 24661390M.

- ^ Elleman, Bruce A. (1998). Diplomacy and deception : the secret history of Sino-Soviet diplomatic relations, 1917–1927. Armonk (N.Y.): M.E. Sharpe. p. 144. ISBN 0765601435.

- ^ "Liang Cheng, The "Diplomatic Hero"". Cultural China. Shanghai News and Press Bureau. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Elleman 1998, p. 145

- ^ Elleman 1998, p. 147

- ^ Elleman 1998, p. 148

- ^ Idema, Wilt (2013). Chinese Studies in the Netherlands: Past, Present and Future. Leiden: Brill. p. 77. ISBN 978-90-04-26312-3.

- ^ Elleman 1998, p. 154

- ^ Elleman 1998, p. 155