Croat–Bosniak War

| Croat–Bosniak War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War and Yugoslav Wars | |||||||||

Clockwise from top right: remains of Stari Most in Mostar, replaced with a cable bridge; French IFOR Artillery Detachment, on patrol near Mostar; a Croat war memorial in Vitez; a Bosniak war memorial in Stari Vitez; view of Novi Travnik during the war | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 40,000–50,000 (1993)[2] | 100,000–120,000 (1993)[3] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

The Croat–Bosniak War was a conflict between the internationally recognized Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the so-called Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, supported by Croatia, that lasted from 18 October 1992 to 23 February 1994.[4] It is often referred to as a "war within a war" because it was part of the larger Bosnian War. In the beginning, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) fought together in an alliance against the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS). By the end of 1992, however, tensions between the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Croatian Defence Council increased. The first armed incidents between them occurred in October 1992 in central Bosnia. The military alliance continued until early 1993, when it mostly fell apart and the two former allies engaged in open conflict.

The Croat–Bosniak War escalated in central Bosnia and soon spread to Herzegovina, with most of the fighting taking place in those two regions. The war generally consisted of sporadic conflicts with numerous short ceasefires. However, it was not an all-out war between Bosniaks and Croats and they remained allied in other regions – mainly Bihać, Sarajevo and Tešanj. Several peace plans were proposed by the international community during the war, but each of them failed. On 23 February 1994, a lasting ceasefire was agreed, and an agreement ending the hostilities was signed in Washington on 18 March 1994, by which time the Croatian Defence Council had significant territorial losses. The agreement led to the establishment of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the resumption of joint operations against Serb forces, which helped alter the military balance and bring the Bosnian War to an end.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) convicted 17 Bosnian Croat officials, six of them for participating with Croatian president Franjo Tuđman and other top Croatian officials in a joint criminal enterprise that sought to annex or control Croat-majority parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks.[5] Two Bosniak officials were also convicted for war crimes committed during the conflict. The ICTY ruled that Croatia had overall control over the Croatian Defence Council and that the Croatian Army had entered Bosnia, which made the conflict international.[6]

Background

In November 1990, the first free elections were held in Bosnia and Herzegovina, putting nationalist parties into power. These were the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), led by Alija Izetbegović, the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), led by Radovan Karadžić, and the Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina (HDZ BiH), led by Stjepan Kljuić. Izetbegović was elected as the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Jure Pelivan, of the HDZ, was elected as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Momčilo Krajišnik, of the SDS, was elected as the speaker of Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[7]

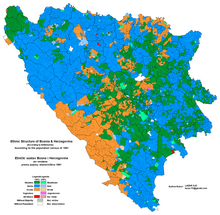

In 1990 and 1991, Serbs in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina had proclaimed a number of "Serbian Autonomous Regions" with the intent of later unifying them to create a Greater Serbia. Serbs used the well equipped Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) in defending these territories.[8] As early as September or October 1990, the JNA had begun arming Bosnian Serbs and organizing them into militias. By March 1991, the JNA had distributed an estimated 51,900 firearms to Serb paramilitaries and 23,298 firearms to the SDS.[9]

In early 1991, the leaders of the six republics began a series of meetings to solve the crisis in Yugoslavia. The Serbian leadership favoured a federal solution, whereas the Croatian and Slovenian leadership favoured an alliance of sovereign states. Izetbegović proposed an asymmetrical federation on 22 February, where Slovenia and Croatia would maintain loose ties with the 4 remaining republics. Shortly after that, he changed his position and opted for a sovereign Bosnia as a prerequisite for such a federation.[10]

The ICTY states that Croatian President Franjo Tuđman's ultimate goal in Bosnia was to create a "Greater Croatia", based on the borders of the Croatian Banovina,[11] which would include western Herzegovina, Posavina and other parts of Bosnia with majority Croat populations. Because he knew the international community opposed the division of Bosnia, Tuđman pursued a dual policy: on the one hand proclaiming his formal support for the unity of Bosnia, while on the other seeking to divide Bosnia between Croats and Serbs.[12] On 25 March 1991, Tuđman met with Serbian president Slobodan Milošević in Karađorđevo, reportedly to discuss the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[13][14]

On 6 June, Izetbegović and Macedonian president Kiro Gligorov proposed a weak confederation between Croatia, Slovenia, and a federation of the other four republics, which was rejected by Milošević.[15] On 13 July, the government of Netherlands, then the presiding EC country, suggested to other EC countries that the possibility of agreed changes to Yugoslav Republics borders should be explored, but the proposal was rejected by other members.[16] In July 1991, Radovan Karadžić, president of the SDS, and Muhamed Filipović, vice president of the Muslim Bosniak Organisation (MBO), drafted an agreement between the Serbs and Bosniaks which would leave Bosnia in a state union with SR Serbia and SR Montenegro. The HDZ BiH and the Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina (SDP BiH) denounced the agreement, calling it an anti-Croat pact and a betrayal. Although initially welcoming the initiative, Izetbegović also dismissed the agreement.[17][18]

From July 1991 to January 1992, during the Croatian War of Independence, the JNA and Serb paramilitaries used Bosnian territory to wage attacks on Croatia.[19] The Croatian government began arming Croats in the Herzegovina region as early as October or November 1991,[20] expecting that the Serbs would spread the war into Bosnia and Herzegovina.[21] It also helped arm the Bosniak community.[19] By late 1991, about 20,000 Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly from the Herzegovina region, enlisted in the Croatian National Guard.[22] During the war in Croatia, Bosnian president Alija Izetbegović gave a televised proclamation of neutrality, stating that "this is not our war", and the Sarajevo government was not taking defensive measures against a probable attack by the Bosnian Serbs and the JNA.[23] Izetbegović agreed to disarm the existing Territorial Defense (TO) forces on the demand of the JNA. This was defied by Bosnian Croats and Bosniak organizations that gained control of many facilities and weapons of the TO.[24][25] On 21 September 1991, Ante Paradžik, the vice-president of the Croatian Party of Rights (HSP) and Croat-Bosniak alliance advocate, was killed by Croatian police in mysterious circumstances.[26]

On 12 November 1991, on a meeting chaired by Dario Kordić and Mate Boban, local party leaders of the HDZ BiH reached an agreement to undertake a policy of achieving an "age-old dream, a common Croatian State" and decided that the proclamation of a Croatian banovina in Bosnia and Herzegovina should be the "initial phase leading towards the final solution of the Croatian question and the creation of a sovereign Croatia within its ethnic and historical [...] borders."[27] On the same day, the Croatian Community of Bosnian Posavina was proclaimed in municipalities of northwest Bosnia. On 18 November, the autonomous Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia (HZ-HB) was established, it claimed it had no secessionary goal and that it would serve a "legal basis for local self-administration". It vowed to respect the Bosnian government under the condition that Bosnia and Herzegovina was independent of "the former and every kind of future Yugoslavia."[28] Boban was established as its president.[29] From its inception the leadership of Herzeg-Bosnia and HVO held close relations to the Croatian government and the Croatian Army (HV).[30] At a session of the Supreme State Council of Croatia, Tuđman said that the establishment of Herzeg-Bosnia was not a decision to separate from Bosnia and Herzegovina. On 23 November, the Bosnian government declared Herzeg-Bosnia unlawful.[31]

The HDZ BiH leadership was split regarding the establishment of the two Croatian communities. The president of the party, Stjepan Kljuić, opposed the move, while party representatives from Herzegovina, Central Bosnia and Bosnian Posavina supported it.[32] On 27 December 1991, the leadership of the HDZ of Croatia and of HDZ BiH held a meeting in Zagreb chaired by Tuđman. They discussed Bosnia and Herzegovina's future, their differences in opinion on it, and the creation of a Croatian political strategy. Kljuić favored that Croats stay within a unified Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Bosniak line. He was criticized by Tuđman for acceding to Izetbegović's policies.[33] Boban held that, in the event of Bosnia and Herzegovina's disintegration or if it remained in Yugoslavia, Herzeg-Bosnia should be proclaimed an independent Croatian territory "which will accede to the State of Croatia but only at such time as the Croatian leadership [...] should decide." Kordić, the vice president of Herzeg-Bosnia, claimed that the spirit of Croats in Herzeg-Bosnia had grown stronger since its declaration and that Croats in the Travnik region were prepared to become a part of the Croatian State "at all costs [...] any other option would be considered treason, save the clear demarcation of Croatian soil in the territory of Herceg-Bosna."[34]

At the same meeting, Tuđman stated that "from the perspective of sovereignty, Bosnia-Herzegovina has no prospects" and recommended that Croatian policy should be one of "support for the sovereignty [of Bosnia and Herzegovina] until such time as it no longer suits Croatia."[35] He based this on the belief that the Serbs did not accept Bosnia and Herzegovina and that Bosnian representatives did not believe in it and wished to remain in Yugoslavia.[33] Tuđman declared "it is time that we take the opportunity to gather the Croatian people inside the widest possible borders".[36] Tudjman then described a proposed partition of Bosnia among Croatia and Serbia, “where Croatia would get the areas...in the community of Herceg-Bosnia and the community of Croatian Posavina, and probably for geopolitical reasons in Cazin, in the Bihać region, which would provide almost optimal satisfaction of Croatian national interests”.[37] From the remainder, Tuđman says a mini-state of Bosnia could be created around Sarajevo that would then serve as a buffer between Croatia and Serbia in the partitioned Bosnia.[37] Tuđman later removed from leadership Stjepan Kljuić and other Bosnian Croats who opposed his plans for dividing Bosnia.[38]

"Just let me tell you. Many who sit here and who support cantonization of Bosnia and Herzegovina will live in a Greater Serbia, and I shall depart for Australia."

On 2 January 1992, Gojko Šušak, the Minister of Defence of Croatia, and JNA General Andrija Rašeta signed an unconditional ceasefire in Sarajevo. The JNA moved relieved troops from the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they were stationed at strategic routes and around major towns.[40] On 16 January, a rally celebrating Croatian independence was held in Busovača. Kordić spoke and declared Croats in Busovača were part of a united Croatian nation and that Herzeg-Bosnia, including Busovača, is "Croatian land and that is how it will be". HVO commander Ignac Koštroman also spoke, stating "we will be an integral part of our dear State of Croatia by hook or by crook."[27] On 27 January the Croatian Community of Central Bosnia was proclaimed.[41]

There was a change in the presidency of the HDZ BiH during winter, probably under influence of the Croatian leadership.[42] On 2 February, Kljuić had resigned. Tuđman commented that "[he] disappeared under Alija Izetbegović's fez and the HDZ [BIH] [...] stopped leading an independent Croatian policy".[43] Milenko Brkić, who also supported an integral Bosnia and Herzegovina, became the new president of HDZ BiH.[42] Bosnian Croat authorities in predominately Croat-populated municipalities answered more to the HDZ leadership and the Zagreb government than the Bosnian government.[44] The HDZ held important positions in the Bosnian government including the premiership and the ministry of defence, but despite this carried out a separate policy.[45]

On 29 February and 1 March 1992, an independence referendum was held in Bosnia and Herzegovina[46][47] and asked "are you in favor of a sovereign and independent Bosnia-Herzegovina, a state of equal citizens and nations of Muslims, Serbs, Croats and others who live in it?"[48] In the meantime Boban publicly circulated an alternative referendum version that designated Bosnia and Herzegovina as a "state community of its constituent and sovereign nations, Croats, Muslims, and Serbs, living on their national territories."[39] Independence was strongly favored by Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, while Bosnian Serbs largely boycotted the referendum. The majority of voters voted for independence and on 3 March 1992 Alija Izetbegović declared independence of the country, which was immediately recognised by Croatia.[46][47]

Following the declaration of independence, the Bosnian War started. In April 1992, the siege of Sarajevo began, by which time the Bosnian Serb-formed Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) controlled 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[49][47] On 8 April, Bosnian Croats were organized into the Croatian Defence Council (HVO).[14] A sizable number of Bosniaks also joined the HVO,[21] constituting between 20 and 30 percent of HVO.[50] Boban said that the HVO was formed because the Bosnian government did nothing after Croat villages, including Ravno, were destroyed by the JNA.[23] A number of them joined the Croatian Defence Forces (HOS), a paramilitary wing of the far-right HSP, led by Blaž Kraljević,[21][51] which "supported Bosnian territorial integrity much more consistently and sincerely than the HVO".[21] However, their views on an integral Bosnia and Herzegovina were related to the legacy of the fascist Independent State of Croatia.[52] On 15 April 1992, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) was formed, with slightly over two-thirds of troops consisting of Bosniaks and almost one-third of Croats and Serbs.[45] The government in Sarajevo struggled to get organized and form an effective military force against the Serbs. Izetbegović concentrated all his forces on retaining control of Sarajevo. In the rest of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the government had to rely on the HVO, that had already formed their defenses, to stop the Serb advance.[14][53]

Political and military relations

A Croat-Bosniak alliance was formed in the beginning of the war, but over time there were notable breakdowns of it due to rising tensions and the lack of mutual trust.[54] Each side held separate discussions with the Serbs, and soon there were complaints from both sides against the other.[55] In February 1992, in the first of several meetings, Josip Manolić, Tuđman's aide and previously the Croatian Prime Minister, met with Radovan Karadžić in Graz, Austria. The Croatian position was not significantly different from that of the Serbs and held that Bosnia and Herzegovina should consist of sovereign constituent nations in a confederal relationship.[39] In mid-April 1992, the HVO proposed a joint military headquarters for the HVO and the TO, but Izetbegović ignored the request.[56] The HVO, on the other hand, refused to be integrated into the ARBiH.[45] On 6 May, Croatian Bosnian leader, Mate Boban, and Serb Bosnian leader, Radovan Karadžić, met in Graz and formed an agreement for a ceasefire[57] and on the territorial division of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croatia and Serbia.[58][59] However, the parties ultimately parted ways and on the following day the JNA and Bosnian Serb forces mounted an attack on Croat-held positions in Mostar.[57][60] On 15 May, the United Nations issued resolution 752 which recognized the presence of JNA and HV soldiers in Bosnia and Herzegovina and demanded that they withdraw.[61] In mid-June, the combined military efforts of the ARBiH and HVO managed to break the siege of Mostar[62] and capture the east bank of the Neretva River, that was under control of the VRS for two months.[63] The deployment of Croat forces to engage the VRS was one of the key obstacles for a total Serb victory in the early stage of the war.[64][65]

The Croatian and Herzeg-Bosnia leadership offered Izetbegović a confederation of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Izetbegović rejected it, whether because he wanted to prevent Bosnia and Herzegovina from coming under the influence of Croatia, or because he thought that such a move would give a justification to Serbian claims, cripple reconciliation between Bosniaks and Serbs and make the return of Bosniak refugees to eastern Bosnia impossible. His attempts to remain neutral were met with disfavor in Croatia, which at the time had different and clearer military and strategic objectives.[66] Izetbegović received an ultimatum from Boban warning him that if he did not proclaim a confederation with Tuđman that Croatian forces would not help defend Sarajevo from strongholds as close as 40 kilometres (25 mi) away.[67] Boban later blocked the delivery of arms to the ARBiH, which were secretly bought despite the United Nations embargo.[68] The Croatian government recommended moving ARBiH headquarters out of Sarajevo and closer to Croatia and pushed for its reorganization in an effort to heavily add Croatian influence.[69]

On 3 July 1992, the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia was formally declared, in an amendment to the original decision from November 1991.[70][66] It claimed power over its own police, army, currency, and education and included several districts where Bosniaks were the majority. It only allowed a Croat flag to be used, the only currency allowed was the Croatian dinar, its official language was Croatian, and a Croat school curriculum was enacted. Mostar, a town where Bosniaks constituted a slight majority, was set as the capital.[63] In the preamble it was attested that "the Croatian people of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in these difficult moments of their history when the last Communist army of Europe, united with the Chetniks, is endangering the existence of the Croatian people and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, are deeply aware that their future lies with the future of the entire Croatian people."[71] In July, Sefer Halilović became the Chief of the General Staff of the ARBiH. This move further damaged relations between Zagreb and Sarajevo as Halilović was an officer in the JNA during the war in Croatia.[66]

Beginning in June, discussions between Bosniaks and Croats over military cooperation and possible merger of their armies started to take place.[72] On 21 July, Izetbegović and Tuđman signed the Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia in Zagreb, Croatia.[73] The agreement allowed them to "cooperate in opposing [the Serb] aggression" and coordinate military efforts.[74] It placed the HVO under the command of the ARBiH.[75] Cooperation was inharmonious, but enabled the transportation of weapons to ARBiH through Croatia in spite of the UN sanctioned arms embargo,[21] reopening channels blocked by Boban.[69] It established "economic, financial, cultural, educational, scientific and religious cooperation" between the signatories. It also stipulated that Bosnian Croats hold dual citizenship for both Bosnia and Herzegovina and for Croatia. This was criticized as Croatian attempts at "claiming broader political and territorial rights in the parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina where large numbers of Croats live". After its signature Boban vowed to Izetbegović that Herzeg-Bosnia would remain an integral part of Bosnia and Herzegovina when the war ended.[69] At a session held on 6 August, the Bosnian Presidency accepted HVO as an integral part of the Bosnian armed forces.[52]

First incidents

Disagreements between Croats and Bosniaks first surfaced over the distribution of arms and ammunition from captured JNA barracks. The first of these disputes occurred in May in Busovača over the Kaonik Barracks and in Novi Travnik over an arms factory and the distribution of supplies from a TO depot. In July, disputes arose in Vareš and in Vitez, where an explosives factory was located, and the HVO secured the JNA barracks in Kiseljak.[76] The two sides also wanted greater political power in various municipalities of central Bosnia.[56] The HVO took full control over Busovača on 10 May and blockaded the town, following an incident in which an HVO member was injured. The HVO gave an ultimatum to the Bosnian Territorial Defense to hand over its weapons and place itself under HVO command, issuing arrest warrants for 3 Muslim leaders, including General Merdan, the latter arrested and beaten up.[77]

In Vitez, an attempt to create a joint unit of the TO and HVO failed and Croats increasingly left the TO forces for the HVO.[56] In May, HVO Major General Ante Roso declared that the only "legal military force" in Herzeg-Bosnia was the HVO and that "all orders from the TO [Territorial Defense] command [of Bosnia and Herzegovina] are invalid, and are to be considered illegal on this territory".[62] On 19 June 1992, an armed confrontation that lasted for two hours occurred between local Bosniak and Croat forces in Novi Travnik.[78] In August, actions by a Muslim gang led by Jusuf Prazina worsened relations with the local HVO in Sarajevo. The HVO also protested to the ARBiH for launching uncoordinated attacks on the VRS from Croat-held areas.[79] After Croat-Bosniak fighting broke out Dobroslav Paraga, leader of the HSP, ordered the HOS not to cooperate with the HVO and was subsequently arrested on terrorist charges.[80]

"HOS, as a regular army in Bosnia-Herzegovina, will fight for the freedom and sovereignty of Bosnia-Herzegovina because it is our homeland [and will] not allow any divisions."

In the summer of 1992, the HVO started to purge its Bosniak members,[82] and many left for ARBiH seeing that Croats had separatist goals.[83] As the Bosnian government began to emphasize its Islamic character, Croat members left the ARBiH to join the HVO or were expelled.[24] At the same time armed incidents started to occur among Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina between the HVO and the HOS.[84] The HVO favored the partition of Bosnia along ethnic lines, while the HOS was a Croatian-Muslim militia who fought for the territorial integrity of Bosnia.[85] The HOS included Croats and Bosniaks in its ranks and initially cooperated with both the ARBiH and the HVO. The two authorities tolerated these forces, although they were unpredictable and used problematic fascist insignia.[51] The HOS, however, did not function integrally throughout the country. In the area of Novi Travnik it was closer to the HVO, while in the Mostar area there were increasingly tense relations between the HOS and the HVO.[52] There, the HOS was loyal to the Bosnian government and accepted subordination to the Staff of the ARBiH of which Kraljević was appointed a member.[86] On 9 August, HOS Commander Blaž Kraljević was killed in unclear circumstances at a police checkpoint in the village of Kruševo,[51] allegedly because his car did not stop at the checkpoint.[87] He and eight of his staff were killed by HVO soldiers under the command of Mladen Naletilić,[88] who supported a split between Croat and Bosniaks.[89] Lukic and Lynch write that Zagreb arranged through the HVO for the ambush and killings of Kraljević and his staff.[82] Dobroslav Paraga, head of the HSP, claimed that the HVO assassinated Kraljević because of an alleged capture of Serb-held Trebinje by HOS forces.[81] The HOS was disbanded, leaving the HVO as the only Croat force.[90]

On 4 September 1992, Croatian officials in Zagreb confiscated a large amount of weapons and ammunition aboard an Iranian plane that was supposed to transport Red Crescent humanitarian aid for Bosnia.[91] On 7 September, HVO demanded that the Bosniak militiamen withdraw from Croatian suburbs of Stup, Bare, Azići, Otes, Dogladi and parts of Nedzarici in Sarajevo and issued an ultimatum.[92] They denied that it was a general threat to Bosnian government forces throughout the country and claimed that Bosniak militiamen killed six of their soldiers, and looted and torched houses in Stup. The Bosniaks stated that the local Croatian warlord made an arrangement with Serb commanders to allow Serb and Croat civilians to be evacuated, often for ransom, but not Bosniaks.[93] On 11 September, at a presidential meeting, Tuđman expressed his desire for a Croatian Banovina.[94] On 14 September, the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared the proclamation of Herzeg-Bosnia unconstitutional.[31] At another presidential meeting on 17 September, Tuđman outlined Croatia's position about organizing BiH into three constituent units, but said that if BiH failed to take into account Croatian interests, he would support Herzeg-Bosnia's secession.[95][96] In late September, Izetbegović and Tuđman met again and attempted to create military coordination against the VRS, but to no avail.[62] By October, the agreement had collapsed and afterwards Croatia diverted delivery of weaponry to Bosnia and Herzegovina by seizing a significant amount for itself.[97] Boban had abandoned a Bosnian government alliance.[98] In November, Izetbegović replaced Kljujić in the state presidency with Miro Lazić from HDZ.[99]

On 5 and 26 October 1992, Jadranko Prlić, the HVO president and Herzeg-Bosnia prime minister, Bruno Stojić, the head of HVO and Herzeg-Bosnia department of defense, Slobodan Praljak, member of the Ministry of Defence of Croatia and commander of the HVO Main Staff, and Milivoj Petković, chief of the HVO Main Staff, acted as a delegation of Croatia and Herzeg-Bosnia and met with Ratko Mladić, the VRS General, with the explicit intent of discussing the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the meeting Praljak stated: "The goal is Banovina or nothing" and that "it is in our interest that the Muslims get their own canton so they have somewhere to move to".[95]

In June 1992 the VRS launched Operation Corridor against HV-HVO forces in Bosnian Posavina to secure an open road between Belgrade, Banja Luka and Knin.[63] The VRS captured Modriča on 28 June, Derventa on 4–5 July and Odžak on 12 July. The outnumbered Croat forces were reduced to isolated positions in Bosanski Brod and Orašje, but were able to repel VRS attacks during August and September. In early October 1992, VRS managed to break through Croat lines and capture Bosanski Brod. HV/HVO withdrew their troops north across the Sava River.[100] Croats and Bosniaks blamed each other for the defeats against the VRS.[101] The Bosnian government suspected that a Croat-Serb cease-fire was brokered,[102] while the Croats objected that the ARBiH was not helping them in Croat-majority areas.[103] By late 1992, Herzeg-Bosnia lost a significant part of its territory to VRS. The territory under the authority of Herzeg-Bosnia became limited to Croat ethnic areas in around 16% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[104] The VRS successes in northern Bosnia resulted in increasing numbers of Bosniak refugees fleeing south towards the HVO-held regions of central Bosnia. In Bugojno and Travnik, Croats found themselves reduced practically overnight from around half the local population to a small minority.[63]

In the latter half of 1992, foreign Mujahideen hailing mainly from North Africa and the Middle East began to arrive in central Bosnia and set up camps for combatant training with the intent of helping their "Muslim brothers" against the Serbs.[105] These foreign volunteers were primarily organized into an umbrella detachment of the 7th Muslim Brigade (made up of native Bosniaks) of the ARBiH in Zenica.[106] Initially, the Mujahideen gave basic necessities including food to local Muslims. When the Croat–Bosniak conflict began they joined the ARBiH in battles against the HVO.[105]

Combatants

Bosniak forces

The Sarajevo government was slow in the organization of an effective military force. Initially they were organized in the Territorial Defence (TO), which had been a separate part of the armed forces of Yugoslavia, and in various paramilitary groups such as the Patriotic League, Green Berets and Black Swans. The Bosniaks had the upper hand in manpower, but were lacking an effective supply of arms and heavy weaponry. The Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was formed in April 1992. Its structure was based on the Yugoslav TO organization. It included 13 infantry brigades, 12 separate platoons, one military police battalion, one engineer battalion, and a presidential escort company.[107]

In August 1992, five ARBiH Corps were established: 1st Corps in Sarajevo, 2nd Corps in Tuzla, 3rd Corps in Zenica, 4th Corps in Mostar and 5th Corps in Bihać. In the second half of 1993 two additional corps were created, the 6th Corps headquartered in Konjic and 7th Corps headquartered in Travnik. The main tactical unit of the ARBiH was a brigade which had three to four subordinate infantry battalions and supporting forces.[108] The size of a brigade varied, it could have as many as 4–5,000 men or fewer than 1,000.[109]

By 1993, the ARBiH had around 20 main battle tanks, including T-55 tanks, 30 APCs and some heavy artillery pieces. In mid 1993, the 3rd ARBiH Corps had 100 120-mm mortars; 10 105-mm, 122-mm, and 155-mm howitzers; 8–10 antiaircraft guns; 25–30 antiaircraft machine guns; two or three tanks; and two or three ZIS 76-mm armored weapons. The Bosniak forces also had 128-mm multiple-barrel rocket launchers, but lacked necessary ammunition.[110] According to a July 1993 estimate by CIA, the ARBiH had 100,000–120,000 men, 25 tanks and less than 200 artillery pieces and heavy mortars. The army had problems with ammunition and rifle shortages and scarce medical supplies.[3]

The ARBiH had logistics centres in Zagreb and Rijeka for the recruitment of men and received weapons and ammunition from Croatia despite the UN arms embargo.[91][111] This practice lasted until at most April 1993. According to Izetbegović, by mid 1993 the ARBiH had brought in 30,000 rifles and machine-guns, 20 million bullets, 37,000 mines, and 46,000 anti-tank missiles.[111]

Croat forces

The Croatian Defence Council (HVO) was formed on 8 April 1992 and was the official military of Herzeg-Bosnia, although the organization and arming of Bosnian Croat military forces began in late 1991. Each district of Herzeg-Bosnia was responsible for its own defence until the formation of four Operative Zones with headquarters in Mostar, Tomislavgrad, Vitez and Orašje. However, there were always problems in coordinating the Operative Zones.[112] The backbone of the HVO were its brigades formed in late 1992 and early 1993. Their organization and military equipment were relatively good, but they could only conduct limited and local offensive action. The brigades usually had three or four subordinate infantry battalions with light artillery, mortars, antitank and support platoons. A brigade numbered from a few hundred to several thousand men; most had 2,000–3,000.[113][114] In early 1993 the HVO Home Guard was formed in order to provide support for the brigades.[115] The HVO forces became better organized as time passed by, but they started creating guards brigades, mobile units of professional soldiers, only in early 1994.[116]

The ICTY found that Croatia exercised overall control over the HVO and that Croatia provided leadership in the planning, coordination and organization of the HVO.[117] The European Community Monitoring Mission (ECMM) estimated the strength of the HVO in the beginning of 1993 at 45,000–55,000. In February 1993, the HVO Main Staff estimated the strength of the HVO at 34,080 officers and men, including 6,000 in Operative Zone Southeast Herzegovina, 8,700 in Operative Zone Northwest Herzegovina, 8,750 in Operative Zone Central Bosnia, and 10,630 in other locations.[118] The HVO headquarters in Mostar declared full mobilization on 10 June 1993. According to The Military Balance 1993–1994 edition, the HVO had around 50 main battle tanks, mainly T-34 and T-55, and 500 various artillery weapons, most of which belonged to HVO Herzegovina.[119] In July 1993, CIA estimated the HVO forces at 40,000 to 50,000 men.[2]

When a ceasefire was signed in Croatia in January 1992, the Croatian government allowed Bosnian Croats in the Croatian Army (HV) to demobilize and join the HVO. HV General Janko Bobetko reorganized the HVO in April 1992 and several HV officers moved to the HVO, including Milivoj Petković.[20] The Zagreb government deployed HV units and Ministry of the Interior (MUP RH) special forces into Posavina and Herzegovina in 1992 to conduct operations against the Serbs together with the HVO.[62][120] The HV and the HVO had the same uniforms and very similar insignia.[121]

During the Croat-Bosniak conflict, HV units were deployed on the frontlines against the VRS in eastern Herzegovina. Volunteers born in Bosnia and Herzegovina, who were former HV members, were sent to the HVO. A unit of deserters was formed in late 1993.[122] Sent units were told to replace their HV insignia with that of the HVO.[123] Most officers in the HVO were actually HV officers.[124] According to a report by the UN Secretary General in February 1994, there were 3,000–5,000 HV soldiers in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[125] The Bosnian government claimed there were 20,000 HV soldiers in BiH in early 1994,[126] while Herzeg-Bosnia officials said only volunteers from BiH, former members of HV, were present.[127] According to The Washington Post, at its peak the amount of money from Croatia that funded the HVO surpassed $500,000 per day.[35] The HVO relied on the HV for equipment and logistical support. Croatian officials acknowledged arming the HVO,[2] but direct involvement of HV forces in the Croat-Bosniak conflict was denied by the Croatian government.[128]

The Croatian Defence Forces (HOS), the paramilitary wing of the Croatian Party of Rights, had its headquarters in Ljubuški. In the beginning of the war they fought against the Serb forces together with the HVO and ARBiH. Relations between the HVO and HOS eventually worsened, resulting in the killing of HOS Commander Blaž Kraljević and the disarmament of the HOS. On 23 August 1992 HVO and HOS leaders in Herzegovina agreed to incorporate the HOS into the HVO. The remaining HOS forces were later recognized by the Sarajevo government as part of the ARBiH. The HOS forces in central Bosnia merged with the HVO in April 1993.[51] Most of the Bosniaks that were members of the HOS joined the Muslim Armed Forces (MOS).[129]

Foreign fighters

Muslim volunteers from different countries started coming to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the second half of 1992.[105] They formed mujahideen fighting groups that were known as El Mudžahid (El Mujahid) that were joined by local radical Bosnian Muslims. The first foreign group to arrive was led by Abu Abdul Al-Aziz from Saudi Arabia.[130][131] Izetbegović and the SDA initially claimed that they had no knowledge of mujahideen units in the region.[132] The mujahideen received financial support from Iran and Saudi Arabia. The El Mudžahid detachment was incorporated into the ARBiH in August 1993. Their strength was estimated at up to 4,000 fighters.[130] These fighters became notorious for the atrocities committed against the Croat population in central Bosnia.[133]

Foreign fighters for Croats included British volunteers as well as other numerous individuals from the cultural area of Western Christianity, both Catholics and Protestants fought as volunteers for the Croats. Albanian, Dutch, American, Irish, Polish, Australian, New Zealand, French, Swedish, German, Hungarian, Norwegian, Canadian and Finnish volunteers were organized into the Croatian 103rd (International) Infantry Brigade. There was also a special Italian unit, the Garibaldi battalion.[134] and one for the French, the groupe Jacques Doriot.[135] Volunteers from Germany and Austria were also present, fighting for the HOS paramilitary group.

Swedish Jackie Arklöv fought in Bosnia and was later charged with war crimes upon his return to Sweden. Later he confessed he committed war crimes on Bosniak civilians in the Croatian camps Heliodrom and Dretelj as a member of Croat forces.[136]

Chronology

Confrontations in Prozor and Novi Travnik

The strained relations led to numerous local confrontations of smaller scale in late October 1992. These confrontations mostly started in order to gain control over military supplies, key facilities and communication lines, or to test the capability of the other side.[137] First of them was an armed clash in Novi Travnik on 18 October. It started as a dispute over a gas station that was shared by both armies. Verbal conflict escalated into an armed one in which an ARBiH soldier was killed. Fighting soon broke out in the entire town. Both the ARBiH and HVO mobilized their units in the area and erected roadblocks. Low-scale conflicts spread quickly in the region.[138][139] The situation worsened on 20 October after HVO Commander Ivica Stojak from Travnik was murdered,[138] for which the HVO accused the 7th Muslim brigade.[140]

The two forces engaged each other along the supply route to Jajce on 21 October,[141] as a result of an ARBiH roadblock at Ahmići set up the previous day on authority of the "Coordinating Committee for the Protection of Muslims" rather than the ARBiH command. ARBiH forces on the roadblock refused to let the HVO go through towards Jajce and the ensuing confrontation resulted in one killed ARBiH soldier. Two days later the roadblock was dismantled.[137] A new skirmish occurred in the town of Vitez the following day.[79] These conflicts lasted for several days until a ceasefire was negotiated by the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).[137]

On 23 October another conflict broke out, this time in Prozor, a town in Northern Herzegovina, in a municipality of around 12,000 Croats and 7,000 Bosniaks. However, the exact circumstances that caused the outbreak are not known.[79] Most of Prozor was soon under control of the HVO, apart from the eastern parts of the municipality.[142] The HVO brought in reinforcements from Tomislavgrad that provided artillery support.[79] By 25 October they took full control of the Prozor municipality. Many Bosniaks fled from Prozor when the fighting started, but they began to return gradually a few days or weeks after the fighting had stopped.[143] After the battle many Bosniak houses were burned.[144] According to a HVO report after the battle, the HVO had 5 killed and 18 wounded soldiers. Initial reports ARBiH Municipal Defence indicated that several hundred Bosniaks were killed, but subsequent reports by the ARBiH made in November 1992 indicated eleven soldiers and three civilians were killed. Another ARBiH report, prepared in March 1993, revised the numbers saying eight civilians and three ARBiH soldiers were killed, while 13 troops and 10 civilians were wounded.[145]

On 29 October, the VRS captured Jajce due to the inability of ARBiH and HVO forces to construct a cooperative defense.[146] The VRS held the advantage in troop size and firepower, staff work, and its planning was significantly superior to the defenders of Jajce.[147] Croat refugees from Jajce fled to Herzegovina and Croatia, while around 20,000 Muslim refugees remained in Travnik, Novi Travnik, Vitez, Busovača, and villages near Zenica.[148]

By November 1992, the HVO controlled about 20 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[62] By December 1992, much of Central Bosnia was contrioled by the Croats.[149] Bosniak authorities forbade Croats from leaving towns such as Bugojno and Zenica, and would periodically organise exchanges of local Croats for Muslims.[106] On 18 December, the HVO took over power in areas that it controlled: it dissolved legal municipal assemblies, sacked mayors and local government members that were against confrontation with Bosniaks, and disarmed remaining Bosniak soldiers except for those in Posavina.[150]

Outbreak of the war

"I will watch them destroy each other and then I will push them both into the sea."

Despite the October confrontation in Travnik and Prozor, and with each side blaming the other for the fall of Jajce, there were no large-scale clashes and a general military alliance was still in effect.[152] A period of rising tensions, followed by the fall of Jajce, reached its peak in early 1993 in central Bosnia.[153] The HVO and ARBiH clashed on 11 January in Gornji Vakuf, a town that had about 10,000 Croats and 14,000 Bosniaks, with conflicting reports as to how the fighting started and what caused it. The HVO had around 300 forces in the town and 2,000 in the surrounding area, while the ARBiH deployed several brigades of its 3rd Corps. A front line was established through the center of town. HVO artillery fired from positions on the hills to the southeast on ARBiH forces in Gornji Vakuf after their demands for surrender were rejected. Fighting also took place in nearby villages, particularly in Duša where a HVO artillery shell killed 7 civilians, including three children. A temporary ceasefire was soon arranged.[154][155]

As the situation calmed in Gornji Vakuf, conflict escalated in Busovača, the HVO's military headquarters in central Bosnia.[156] On 24 January 1993, the ARBiH ambushed and killed two HVO soldiers outside of the town in the village of Kaćuni.[154] On 26 January, six Croats and a Serb civilian were executed by the ARBiH in the village of Dusina near Zenica, north of Busovača.[157] The following day HVO forces blocked all roads in central Bosnia and thus stopped the transports of arms to the ARBiH. Intense fighting continued in the Busovača area, where the HVO attacked the Kadića Strana part of the town, in which numerous Bosniak civilians were expelled or killed,[158] until a truce was signed on 30 January.[159]

The HVO had 8,750 men in its Operative Zone Central Bosnia. The ARBiH 3rd Corps, which was based in central Bosnia, reported that during this period it had roughly 26,000 officers and men.[118] The 3:1 ratio in central Bosnia was a result of an expansion in Bosniak forces throughout 1993, which was reflected in increased arms transfers, the influx of refugees from Jajce, military-age refugees from eastern Bosnia and the arrival of fundamentalist mujahideen fighters from abroad.[160][161] By early 1993 the ARBiH also had an armaments advantage over the HVO central Bosnia.[162] This made it possible for the ARBiH to conduct offensive action on a large scale for the first time.[161] The increase in the relative power of the Bosniak side led to a change in relationship between Croats and Bosniaks in central Bosnia.[160] Despite the growing tensions, the transfer of weapons from Croatia to BiH continued throughout March and April.[163]

Vance–Owen Peace Plan

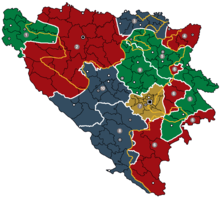

The UN, the United States, and the European Community (EC) supported a series of peace plans for Bosnia and Herzegovina.[53] The most notable of them was a peace proposal drafted by the UN Special Envoy Cyrus Vance and by EC representative Lord Owen. The first draft of the plan was presented in October 1992, taking into account the aspirations of all three sides.[164] The Vance–Owen Peace Plan (VOPP) proposed to divide Bosnia into ten ethnically based autonomous provinces or cantons, three of which would be Serb, three Bosniak, three would be Croat, and Sarajevo would be a separate province.[156][165]

The final draft was presented in Geneva in January 1993, but it created an impression that the borders were not yet definite.[166] Bosnian Croat representatives supported the peace proposal as it gave them autonomy. Only a few Croat enclaves were outside the three Croat provinces and it was more favourable to them than the previous plans.[167] Tuđman was unofficially the head of the Croat delegation as Boban required his approval before acting.[168] On 2 January, Bosnian Croat authorities agreed to the plan in its entirety.[169] On 15 January the HVO declared that it would implement the plan unilaterally even without the signature of Bosniak authorities.[170] On the same day, Prlić ordered ARBiH units in provinces designated as Croat under the plan to subordinate themselves to HVO, and HVO units in Bosniak designated provinces to subordinate to the ARBiH.[169] Stojić and Petković sent similar orders.[171]

On 16 January, Halilović reminded ARBiH troops that peace talks were still ongoing and were ordered to not subordinate to the HVO.[172] On the same day, Božo Rajić, a Croat and Minister of Defence of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, issued an identical order to that of the HVO to Serb, Croat, and Bosniak forces as well as UNPROFOR and ECMM. Owen says this was premature and that the ARBiH was not required to be subordinate to the HVO.[173] On 19 January, Izetbegović voided Rajić's order and on 21 January, Rajić suspended his own order until peace talks were finished.[172] At the same time, HVO-ARBiH clashes broke out in many municipalities.[172] A mutual order to halt hostilities was issued by Boban and Izetbegović on 27 January though it went unenforced.[174]

Izetbegović had rejected the plan as he pressed for a unitary state and said that the plan would "legitimise Serb ethnic cleansing". Bosnian Serbs also rejected it because they would have to withdraw from more than 20% of the territory of BiH they controlled and split their state into three parts,[165] though Karadžić refused to give a direct answer immediately.[175] The Croat leadership tried to implement the plan unilaterally, despite that the Bosniak and Serb parties did not sign it yet.[176]

EC representatives wanted to sort out the Croat-Bosniak tensions, but the collective Presidency fell apart, with the Croat side objecting that decisions of the government were made arbitrarily by Izetbegović and his close associates.[177] The US then put pressure on Izetbegović to sign it, hoping that if the Bosniaks agreed on it, Russia would persuade the Bosnian Serbs to also accept the plan.[178] A Bosniak revision of the proposal was published in an SDA magazine with a map allocating province 10 municipalities of Travnik, Novi Travnik, Vitez, Busovača, Bugojno and Gornji Vakuf to a Bosniak province, areas in which the Croat-Bosniak conflict soon erupted.[175]

Izetbegović eventually accepted the plan on 25 March after several amendments,[179] and on 11 May, the Assembly of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina passed a decision in support of the plan and with assurance of government enforcement.[180] Although initially Karadžić rejected the plan, he signed it on 30 April, but it was rejected by the National Assembly of Republika Srpska on 6 May, and subsequently rejected on a referendum.[181]

Many thought that this plan contributed to the escalation of the Croat-Bosniak war, encouraging the struggle for territory between Croat and Bosniak forces in parts of central Bosnia that were ethnically mixed.[166] In May, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Tadeusz Mazowiecki said that the Vance-Owen plan was encouraging ethnic cleansing.[152] Owen later defended his plan against such claims, saying that those who connect ethnic cleansing and a civil war between the Croats and Bosniaks to the Vance-Owen Peace Plan are wrong as their alliance was breaking apart throughout 1992.[182] On 20 May, Tuđman claimed that the "Croats surely cannot agree to lose some areas that used to be a part of the Banovina."[183]

April 1993 in central Bosnia

On 28 March Tuđman and Izetbegović announced an agreement to establish a joint Croat-Bosniak military in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The HVO and ARBiH were to be placed under joint command. However, in the following month the war further escalated in central Bosnia.[159] The Croats attributed the escalation to the increased Islamic policy of the Sarajevo Government, while Bosniaks accused the Croat side of separatism.[184] The escalation was condemned by both the Islamic Community of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Catholic Church, which held the SDA and HDZ leadership responsible.[185] In April, the Reis ul-ulema in the Islamic Community, Jakub Selimoski, who opposed political Islam, was deposed and replaced with Mustafa Cerić, a more radical imam who had close ties with the SDA leadership.[185][186] In central Bosnia, there was a large scale effort by the HVO to transfer the Croat population into Herzegovina.[187]

The thin ARBiH-HVO alliance broke after the HVO issued an ultimatum for ARBiH units in Croat-majority cantons, designated by the null Vance-Owen Plan, to surrender their arms or move to a Bosniak-majority canton by 15 April.[159] In early April armed clashes started in Travnik when a Bosniak soldier fired on HVO soldiers erecting a Croat flag. On 13 April, four members of the HVO were kidnapped by the mujahideen outside Novi Travnik.[188] In the morning of 15 April, HVO commander Živko Totić was kidnapped in Zenica and his escort was killed by the mujahideen. The ARBiH representatives denied any involvement in this, and a joint ARBiH-HVO commission was formed to investigate the case.[189][159] The prisoners were subsequently exchanged in May for eleven mujahideen and two Muslim drivers arrested by the HVO.[190] On the following morning shooting broke out in Zenica, where the outnumbered HVO was forced out of the city.[191] Most of the Croat population in Zenica was expelled and became refugees.[192] Captured soldiers and civilians were detained in a music school.[193]

Clashes spread down the Lašva Valley in central Bosnia. The HVO wanted to link up the towns of Kreševo, Kiseljak, Vitez, Busovača and Novi Travnik, which would have created a corridor across central Bosnia.[194] An offensive was launched in which the HVO Commander Dario Kordić implemented an ethnic cleansing strategy in the Lašva Valley to expel the Bosniak population.[191][158] The massacre in Ahmići on 16 April 1993 was the culmination of the operation. The village of Ahmići was attacked by surprise in the morning with mortar rounds and sniper fire. The attack resulted in mass killing of at least 103 Bosniak civilians, including 32 women and 11 children.[195] The main mosque was burned and its minaret demolished.[191][196] The attack was preplanned and resulted in a "deliberate massacre of unarmed, unwarned civilians: HVO troops systematically set out to find and execute the entire population." Afterwards a cleanup operation was carried out to disguise what had occurred.[191]

On 18 April, a truck bomb was detonated near the mosque in Stari Vitez, resulting in the destruction of the War Presidency office, the deaths of at least six people and injury to 50 people. The ICTY determined this was an act of "pure terrorism" carried out by elements within the HVO, but did not link the attack to the HVO leadership.[197] The HVO encircled Stari Vitez where the ARBiH deployed in trenches and shelters with around 350 fighters. Bosniak forces tried to break through from the north and reinforce the ARBiH positions in Stari Vitez.[198] The HVO took control of several villages around Vitez, but the lack of resources slowed their advance and the plan of linking the Vitez enclave with Kiseljak. The ARBiH was numerically superior and its several hundred soldiers remained in Vitez.[199] The explosives factory located in Vitez remained under HVO control.[200] The siege on Stari Vitez continued from April 1993 to February 1994.[197] On 24 April, mujahideen forces attacked the village of Miletići near Travnik, north of Vitez. Upon taking it they mutilated four captured Croat civilians and took the rest to the Poljanice camp.[157]

Fierce fighting occurred in the Kiseljak area. HVO attacked and gained control of several Bosniak villages in the vicinity by the end of April. Bosniak civilians were detained or forced to leave and the villages sustained significant damage.[199] In Busovača, the ARBiH opened artillery and mortar fire on the town and attacked it on 19 April. Intense combat continued for three days.[201] Bosniaks were expelled from several villages near the town. The HVO also launched attacks on Gornji Vakuf, Prozor and Jablanica, while the ARBiH attacked HVO positions east of Prozor.[199]

HVO HQ said that their losses were 145 soldiers and 270 civilians killed by 24 April, and ARBiH casualties were probably at least as high. In the following period the HVO in central Bosnia assumed a defensive position against the 3rd ARBiH Corps.[199] The HVO overestimated their power and the ability of securing the Croat enclaves, while the ARBiH leaders thought that Bosniak survival depended on seizing territory in central Bosnia rather than in a direct confrontation with the stronger VRS around Sarajevo.[101] Within two months the ARBiH fully controlled Central Bosnia except for Vitez, Kiseljak, and Prozor.[202]

War spreads to Herzegovina

By the end of April the Croat-Bosniak war had fully broken out. On 21 April, Šušak met with Lord Owen in Zagreb, where he expressed his anger at the behavior of Bosniaks and said that two Croat villages in eastern Herzegovina had put themselves into Serb hands rather than risking coming under Bosniak control.[203] Šušak, himself a Bosnian Croat,[146] was one of the chief supporters of Herzeg-Bosnia in the government,[204][90] and according to historian Marko Attila Hoare acted as a "conduit" of Croatian support for Bosnian Croat separatism.[146]

The war had spread to northern Herzegovina, firstly to the Konjic and Jablanica municipalities. The Bosniak forces in the region were organized in three brigades of the 4th Crops and could field around 5,000 soldiers. The HVO had fewer soldiers and a single brigade, headquartered in Konjic. Although there was no conflict in Konjic and Jablanica during the Croat-Bosniak clashes in central Bosnia, the situation was tense with sporadic armed incidents. The conflict started on 14 April with an ARBiH attack on a HVO-held village outside of Konjic. The HVO responded with capturing three villages northeast of Jablanica.[205] On 16 April in the village of Trusina, north of Jablanica, 18 Croat civilians (including two children) and 4 POWs were killed by an ARBiH unit called the Zulfikar upon taking the village.[206] On the following day the HVO attacked the villages of Doljani and Sovići east of Jablanica. After taking control of the villages around 400 Bosniak civilians were detained until 3 May.[207] The HVO and ARBiH fought in the area until May with only several days of truce, with the ARBiH taking full control of both the towns of Konjic and Jablanica and smaller nearby villages.[205]

On 25 April, Izetbegović and Boban signed a joint statement ordering a ceasefire between the ARBiH and the HVO.[208] It declared a joint HVO-ARBiH command was created and to be led by General Halilović and General Petković with headquarters in Travnik. On the same day, however, the HVO and the HDZ BiH adopted a statement in Čitluk claiming Izetbegović was not the legitimate president of Bosnia and Herzegovina, that he represented only Bosniaks, and that the ARBiH was a Bosniak military force.[209]

There were areas of the country where the HVO and ARBiH continued to fight side by side against the VRS. Although the armed confrontation in Herzegovina and central Bosnia strained the relationship between them, it did not result in violence and the Croat-Bosniak alliance held, particularly in places in which both were heavily outmatched by Serb forces. These exceptions were the Bihać pocket, Bosnian Posavina and the Tešanj area. Despite some animosity, an HVO brigade of around 1,500 soldiers also fought along with the ARBiH in Sarajevo.[210][211] In other areas where the alliance collapsed, the VRS, still the strongest force, occasionally cooperated with both the HVO and ARBiH, pursuing a local balancing policy and allying with the weaker side.[212]

Siege of Mostar

Meanwhile, tensions between Croats and Bosniaks increased in Mostar. By mid-April 1993, it had become a divided city with the western part dominated by HVO forces and the eastern part where the ARBiH was largely concentrated. While the ARBiH outnumbered the HVO in central Bosnia, the Croats held the clear military advantage in Herzegovina. The HVO headquarters was in western Mostar.[213] The 4th Corps of the ARBiH was based in eastern Mostar and under the command of Arif Pašalić.[214] The HVO Southeast Herzegovina, which had an estimated 6,000 men in early 1993, was under the command of Miljenko Lasić.[137] The conflict in Mostar started in the early hours of 9 May 1993 when both the east and west side of Mostar came under artillery fire. As in the case of Central Bosnia, there exist competing narratives as to how the conflict broke out in Mostar.[213] Combat mainly took place around the ARBiH headquarters in Vranica building in western Mostar and the HVO-held Tihomir Mišić barracks (Sjeverni logor) in eastern Mostar. After the successful HVO attack on Vranica, 10 Bosniak POWs from the building were later killed.[215] The situation in Mostar calmed down by 21 May and the two sides remained deployed on the frontlines.[216] The HVO expelled the Bosniak population from western Mostar, while thousands of men were taken to improvised prison camps in Dretelj and Heliodrom.[217] The ARBiH held Croat prisoners in detention facilities in the village of Potoci, north of Mostar, and at the Fourth elementary school camp in Mostar.[218]

On 30 June the ARBiH captured the Tihomir Mišić barracks on the east bank of the Neretva, a hydroelectric dam on the river and the main northern approaches to the city. The ARBiH also took control over the Vrapčići neighborhood in northeastern Mostar. Thus they secured the entire eastern part of the city. On 13 July the ARBiH mounted another offensive and captured Buna and Blagaj, south of Mostar. Two days later fierce fighting took place across the frontlines for control over northern and southern approaches to Mostar. The HVO launched a counterattack and recaptured Buna.[214] Both sides settled down and turned to shelling and sniping at each other, though the HVO superior heavy weaponry caused severe damage to eastern Mostar.[217] In the broader Mostar area the Serbs provided military support for the Bosniak side and hired out tanks and heavy artillery to the ARBiH. The VRS artillery shelled HVO positions on the hills overlooking Mostar.[219][185] In July 1993, Bosnian Vice President Ejup Ganić said that the biggest Bosniak mistake was a military alliance with the Croats at the beginning of the war, adding that Bosniaks were culturally closer to the Serbs.[220]

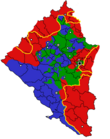

Before the war, the Mostar municipality had a population of 43,037 Croats, 43,856 Bosniaks, 23,846 Serbs and 12,768 Yugoslavs.[221] According to 1997 data, the municipalities of Mostar that in 1991 had a Croat relative majority became all Croat and municipalities that had a Bosniak majority became all Bosniak.[222] Around 60 to 75 percent of buildings in the eastern part of the city were destroyed or very badly damaged, while in the larger western part around 20 percent of buildings had been severely damaged or destroyed.[223]

June–July 1993 Offensives

Contest of Travnik and Kakanj

In central Bosnia, the situation between Bosniaks and Croats remained relatively calm during May. The Sarajevo government used that time to reorganize its army, naming Rasim Delić as Commander of the ARBiH, and to prepare an offensive against the HVO in the Bila Valley, where the city of Travnik was located, and in the Kakanj municipality. By April, the ARBiH in the Travnik area had around 8,000–10,000 men commanded by Mehmed Alagić. The HVO had some 2,500–3,000 soldiers, most of them on the defence lines against the VRS. The HVO had its headquarters in Travnik, but the city was controlled by the ARBiH.[224]

On 4 June the ARBiH attacked HVO positions in Travnik and its surroundings. The HVO units holding the front lines were struck from the rear and the headquarters in Travnik was surrounded. After a few days of street fighting the outnumbered HVO forces were defeated. Thousands of civilians and HVO soldiers fled to nearby Serb-held territory as they were cut off from HVO held positions.[225][226] On 8 June the village of Maline near Travnik was captured by the mujahideen. More than 200 Croat civilians and soldiers were imprisoned. At least 24 Croat civilians and POWs were subsequently killed by mujahideen forces near the village of Bikoši northeast of Travnik.[227] The seizure of Travnik and its surrounding villages triggered a large exodus of Croats from the area.[217] Captured civilians and POWs were detained by the ARBiH in a cellar of the JNA barracks in Travnik.[228]

The ARBiH continued its offensive to the east of the city and secured a corridor from Zenica to Travnik. The HVO was pushed to Novi Travnik and Vitez.[225][226] On 10 June the ARBiH shelled Vitez, during which eight children had been killed in a playground by an artillery shell.[133] Due to the advancement of Bosniak forces, the HVO headquarters in Mostar declared full mobilization on the territory of Herzeg-Bosnia.[229]

In early June a convoy of aid supplies known as the Convoy of Joy was heading for Tuzla. It was stopped on June 10 by Croat refugees from Travnik when around 50 women blocked the road north of Novi Travnik. The convoy was then looted and eight drivers were killed. The following morning the convoy moved on, but incidents continued to happen. In one of them the UNPROFOR escort returned fire and killed two HVO soldiers in the shootout.[230] This incident was extensively reported in the Western media and caused immense bad publicity for the HVO.[217]

The ARBiH moved on towards Kakanj with an attack on villages to the southeast of the city. As the ARBiH approached the city, thousands of Croats began to flee, and the outnumbered HVO directed its forces to protect an escape route to Vareš, east of Kakanj. The key villages on the route were captured on 15 June and on the following day the ARBiH entered Kakanj.[231] The HVO responded with attacks in the Kiseljak area. After taking the village of Tulica south of the town, HVO forces killed 12 Bosniak civilians and POWs and burned several houses. In the Han Ploča and Grahovci villages north of Tulica, 64 people were killed during the attack or in custody.[232]

Tuđman came under intense pressure both from the EC for giving aid to the HVO and from the Herzeg-Bosnia leaders that asked for more military support. The HV eventually assumed control of the entire confrontation line with the VRS in southern Herzegovina, north of Dubrovnik, which enabled the HVO to direct more of its troops against the ARBiH.[233] The HV remained there in defensive positions until the signing of the Dayton agreement.[20] Martin Špegelj, former Minister of Defence, later said that he was asked to help "rescue the situation" in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but refused it. He believed that if the Croatian Army remained in an alliance with the ARBiH then the war against the Serbs would have been concluded by the end of 1992.[234][123]

Battle of Žepče

In the town of Žepče, 45 kilometers northeast of Zenica, Croats and Bosniaks had two parallel governments. The town of 20,000 residents was equally divided and coexistence between Croats and Bosniaks had been retained. The ARBiH and HVO maintained separate headquarters a kilometer apart.[235]

HVO troops in the region numbered 7,000 men, of which 2,000 were in the immediate Žepče area. The ARBiH had two local brigades in Žepče and Zavidovići with around 5,000–6,000 men. The ARBiH also had several brigades in Tešanj and Maglaj, north of Žepče. Both armies were positioned on the frontlines against the VRS, but their cooperation broke down on 24 June, with both sides accusing each other for the conflict outbreak. The ARBiH deployed 12,500 men south of Žepče, advancing in two columns. These units occupied the high ground east, south, and west of Žepče, while bitter street fighting took place in the town between the HVO and local Bosniak forces. Each side controlled about half of Žepče and used artillery for heavy bombardment. An undisguised Croat-Serb alliance existed with the UN confirming that VRS tanks helped the HVO in the Žepče-Zavidovići area. Local VRS forces in Maglaj provided decisive support for the HVO, succeeding where the HVO failed in crippling ARBiH defense. The battle of Žepče lasted until 30 June when the 305th and 319th ARBiH Brigades surrendered. The ARBiH troops secured Zavidovići, but the Bosniak-held area around Tešanj and Maglaj was completely cut off.[235][236]

As a result of VRS assistance the HVO gained the upper hand by early July. The UN confirmed that Maglaj was completely surrounded.[237] Around 4,000–5,000 Bosniak POWs and civilians were detained by the HVO after the end of the battle and held in warehouses for several days until their release. Captured ARBiH soldiers received harsh treatment.[238] The area of Žepče, Maglaj and Tešanj became a three-sided war. In the Žepče-Zavidovići area the VRS assisted the HVO against the ARBiH, Maglaj was surrounded by the HVO on three sides and the VRS on one side, and in Tešanj the HVO and ARBiH cooperated against the VRS.[237]

Battle of Bugojno

In early morning of 18 July the ARBiH attacked HVO forces in and around Bugojno, where an ammunition factory was located. Previously, the two armies' commanders allowed free movement of the troops in the town, but this agreement was shaken by incidents that happened throughout the year.[239] The ARBiH had the upper hand in the battle of Bugojno. The HVO had several hundred soldiers in the town, whereas the ARBiH deployed three times as many soldiers.[233][240][239] The HVO's Eugen Kvaternik brigade, disorganized and surprised, was quickly surrounded in three separate places. After heavy street fighting, the ARBiH captured HVO's barracks on 21 July and by 25 July it seized control of the town,[239] triggering the flight of around 15,000 Croats.[217] HVO soldiers and non-Bosniak civilians were transferred to prison camps, mostly to the Iskra Stadium Camp where they were held for months in deplorable conditions.[241][242] In the fighting several dozens of soldiers died on both sides while 350 HVO soldiers were captured.[239] From July, the HVO's Operative Zone Central Bosnia was completely cut off from HVO Herzegovina and could not receive any significant amounts of military supplies.[243]

Kiseljak enclave

In July, the ARBiH was tightening its grip on Kiseljak and Busovača and pushed closer towards Vitez and Novi Travnik.[244] Due to its location on the outskirts of the besieged Sarajevo, the Kiseljak enclave was an important distribution center of smuggled supplies on the route to Sarajevo.[245] Bosniaks and Croats both wanted control over it. Until the summer, most of the fighting took place in the northern area of the enclave and west of the town of Kiseljak. During the April escalation, the HVO gained control over villages in that area. Another round of fighting started in mid June when the ARBiH attacked HVO-held Kreševo, south of Kiseljak.[246] The attack started from the south of the town and was followed by a strike on villages north and northeast of Kiseljak. The ARBiH deployed parts of its 3rd and 6th Corps, about 6–8,000 soldiers versus around 2,500 HVO soldiers in the enclave.[247] The attack on Kreševo was repelled after heavy fighting and the HVO stabilized its defence lines outside the town. The next target of the ARBiH was Fojnica, a town west of Kiseljak. The attack began on 2 July with artillery and mortar attacks, just days after the UNPROFOR Commander called the town "an island of peace". Fojnica was captured in the following days.[246]

Contest of Gornji Vakuf

Following the successful capture of Bugojno, the ARBiH was preparing an offensive on Gornji Vakuf, where both sides held certain parts of the town. The ARBiH launched its attack on 1 August and won control over most of the town by the following day. The HVO retained control over a Croat neighborhood in the southwest and the ARBiH, lacking necessary reinforcements, could not continue its offensive. The name of the Croat-held part is called Uskoplje (name applies to the entire town historically). The HVO attempted a counterattack from its positions to the southwest of the town on 5 August, but the ARBiH was able to repel the attack. Another attack by the HVO started in September, reinforced with tanks and heavy artillery, but it was also unsuccessful.[248]

Operation Neretva

The standstill of August ended in early September when the ARBiH launched an operation known as Operation Neretva '93 against the HVO on a 200 km front from Gornji Vakuf to south of Mostar, one of its largest of the year. The ARBiH launched coordinated attacks on Croat enclaves in Lašva Valley, particularly in the Vitez area.[249] The village of Zabilje north of Vitez was the first target in order to cut the main road through the Lašva Valley. Repeated attacks followed from northwest and southwest. The HVO launched a counterattack on 8 September against ARBiH positions northwest of Vitez. They seized the high ground on the strategically important Bila hill, but the Bosniak forces soon resumed their offensive.[250][251]

During the night of 8/9 September, the ARBiH attacked the village of Grabovica, near Jablanica. At least 13,[252] and as many as 35,[253] Croat civilians were killed in the Grabovica massacre. The victims included elderly people, women, and a four-year-old child.[252] A few days later the ARBiH mounted an offensive east of Prozor. During this offensive the Uzdol massacre occurred in the village of Uzdol. In the morning of 14 September, 70–100 ARBiH forces infiltrated past the HVO defence lines and reached the village. After capturing the HVO command post the troops went on a killing spree;[254] 29 Croat civilians, including 3 children, were killed by the Prozor Independent Battalion and members of the local police force.[252][254]

On 18 September another ARBiH attack started in the Vitez area in order to split the Croat enclave into two parts.[255] Combat renewed in other areas as well, in Gornji Vakuf, Travnik, Fojnica and Mostar.[251] Fighting shifted to the Busovača area on 23 September where the ARBiH used 120-mm mortar rounds to shell the town. Vitez was again struck on 27 September, when its hospital was hit by ARBiH mortars, killing two people. During a simultaneous attack from the north and south, at one point the ARBiH broke through HVO lines in Vitez, but were ultimately forced back after heavy fighting.[255][249]

In Herzegovina, the main focus of the ARBiH attack was the HVO stronghold in the village of Vrdi, an important location for the control of northern and western approaches to Mostar. The first attack started on 19 September with artillery bombardment of the village. It included the struggle for nearby mountains to the west, but the attack was repelled by the HVO. There was no fixed frontline from Vrdi to Mostar and forces from both sides battled on the hills. In Mostar, there were clashes in the suburbs of the city and mutual artillery shelling until a ceasefire was agreed on 3 October.[256]

Vareš enclave

The town of Vareš held 12,000 residents with a small Croat majority. It had been relatively free of ethnic tensions even after the summer of 1993. In the town leaders of both sides remained moderate and the Bosniak and Croat communities carried on coexisting. Issues first started in mid-June when an ARBiH counteroffensive pushed the Croat population of Kakanj out with around 12,000–15,000 Croat refugees coming to Vareš and nearby villages, effectively doubling Vareš's population. The Croats, having more people than houses, responded by forcing Bosniaks from their homes in three villages outside Kakanj on 23 June and demanded that nearby villages surrender their arms to the HVO, a demand that appeared to be ignored. The HVO had military control of Vareš and was pressured by the ARBiH to resubordinate from the HVO's Central Bosnia Operational Zone to the ARBiH 2nd Corps. The Croats in Vareš attempted to balance their relationship with the Bosniaks and Herzeg-Bosnia.[257]

Ivica Rajić, commander of the HVO Central Bosnia Operational Zone's Second Operational Group, traveling through friendly Serb territory had reached Vareš on or before 20 October and changed the situation greatly. In Vareš he and an armed extremist group carried out a local coup, jailing and replacing the mayor and police chief. The municipality's large Bosniak population was then harassed, robbed, and systemically forced from their houses. Within days the majority of the Bosniak population had relocated south to the village of Dabravina. Rajić established a hardliner government while the ARBiH was preparing to attack Vareš. The ARBiH began with the town of Ratanj between Kakanj and Vareš and moved on to the predominately Croat village of Kopjari where three HVO soldiers were killed and the town's population was forced to flee. The attack infuriated Rajić and ordered that the HVO assault a Bosniak village in retaliation.[257]

On the morning of 23 October 1993, HVO infantry, likely with mortar and artillery support, attacked the village of Stupni Do in Vareš, which was guarded by an ARBiH platoon with 39 soldiers. In the process HVO soldiers destroyed the village, dynamited and looted buildings, and killed any resident that did not manage to flee in time.[258][259] The ICTY determined that the HVO massacred 36 people, including three children, and that three women were raped.[259] The HVO denied the massacre and prevented UN peacekeepers from investigating by planting mines and threatening them with anti-tank weapons. By the time peacekeepers gained access on 26 October the HVO had cleaned up the town, removing and destroying evidence of the massacre.[258]

By the end of October, Vareš was completely cleansed of its Bosniak inhabitants, with its Croat residents looting abandoned Bosniak homes and businesses. On 3 November the ARBiH captured an empty Vareš with no bloodshed and afterwards a number of drunk and disorderly ARBiH soldiers looted what Croats had left behind. Previously ejected Bosniaks returned to their houses while those belonging to Croats were occupied by Bosniaks that were ethnically cleansed from other places of Bosnia due to the Croat-Bosniak war.[257] The HVO had hoped the attack in Stupni Do would provoke an ARBiH counterattack that would push the Croat population out in order for the HDZ leadership to resettle it in "Croat territory" elsewhere.[260] Most of Vareš's Croat population had fled to Kiseljak. Within weeks the demographics of Vareš had gone from being ethnically-mixed, to exclusively Croat, and then to majority Bosniak.[257]

Owen–Stoltenberg plan

In late July 1993 the Owen–Stoltenberg Plan was proposed by U.N. mediators Thorvald Stoltenberg and David Owen, which would organize Bosnia and Herzegovina into a union of three ethnic republics.[261] Serbs would receive 53 percent of territory, Bosniaks would receive 30 percent, and Croats 17 percent. The Croats accepted the proposal, although they had some objections regarding the proposed borders. The Serbs also accepted the proposal, while the Bosniak side rejected the plan, demanding access to the Sava River and territories in eastern and western Bosnia from the Serbs and access to the Adriatic Sea from the Croats. On 28 August, in accordance with the Owen–Stoltenberg peace proposal, the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia was proclaimed in Grude as a "republic of the Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina".[262][125] However, it was not recognised by the Bosnian government.[263]

On 7 September 1993 the Parliament of Croatia recognized Herzeg-Bosnia as a possible form of sovereignty for the Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[264] On 14 September, Tuđman and Izetbegović signed a joint declaration to stop all hostilities between the ARBiH and HVO.[265] A few days after the Tuđman–Izetbegović declaration, Izetbegović and Momčilo Krajišnik agreed to stop all hostilities between the VRS and ARBiH and negotiate their territorial disputes. A provision was included in their declaration that after agreeing on the borders, each republic could organize a referendum on independence.[265] Talks between all three parties continued on 20 September on HMS Invincible.[266] Although Izetbegović was in favour of a peace agreement, the military leaders wanted to continue the war, particularly against the Croats.[267] The September attempt at reconciliation of the Croat and Bosniak sides was thus sunk as the ARBiH leaders thought that they could defeat the Croats in central Bosnia, and fighting in central Bosnia and Mostar continued.[125][268] On 22 October, Tuđman instructed Šušak and Bobetko to continue to support Herzeg-Bosnia, believing that "the future borders of the Croatian state are being resolved there."[35] On 28 November, Tuđman told Boban and Šušak that "if we get borders Novi Travnik, Busovača, Bihać and if we cleanse Baranja, we can give up majority of areas around Sava."[269]

Winter stalemate