Boshin War

| Boshin War 戊辰戦争 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Meiji Restoration | |||||||

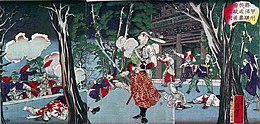

The Battle of Ueno, Yoshimori Utagawa, 1869 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| 1868 |

1868 | ||||||

|

1869 |

1869 | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

1868–1869

|

1868 1869 | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120,000 | 150,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,125+ killed and wounded | 4,550+ killed, wounded and captured | ||||||

| Total: 8,200 killed and 5,000+ wounded[2] | |||||||

The Boshin War (戊辰戦争, Boshin Sensō), sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a coalition seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperial Court.

The war stemmed from dissatisfaction among many nobles and young samurai with the shogunate's handling of foreigners following the opening of Japan during the prior decade. Increasing Western influence in the economy led to a decline similar to that of other Asian countries at the time. An alliance of western samurai, particularly the domains of Chōshū, Satsuma, and Tosa, and court officials secured control of the Imperial Court and influenced the young Emperor Meiji. Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the sitting shōgun, realizing the futility of his situation, abdicated and handed over political power to the emperor. Yoshinobu had hoped that by doing this the House of Tokugawa could be preserved and participate in the future government.

However, military movements by imperial forces, partisan violence in Edo, and an imperial decree promoted by Satsuma and Chōshū abolishing the House of Tokugawa led Yoshinobu to launch a military campaign to seize the emperor's court in Kyoto. The military tide rapidly turned in favour of the smaller but relatively modernized Imperial faction, and, after a series of battles culminating in the surrender of Edo, Yoshinobu personally surrendered. Those loyal to the Tokugawa shōgun retreated to northern Honshū and later to Hokkaidō, where they founded the Republic of Ezo. The defeat at the Battle of Hakodate broke this last holdout and left the Emperor as the de facto supreme ruler throughout the whole of Japan, completing the military phase of the Meiji Restoration.

Around 69,000 men were mobilized during the conflict, and of these about 8,200 were killed. In the end, the victorious Imperial faction abandoned its objective of expelling foreigners from Japan and instead adopted a policy of continued modernization with an eye to the eventual renegotiation of the unequal treaties with the Western powers. Due to the persistence of Saigō Takamori, a prominent leader of the Imperial faction, the Tokugawa loyalists were shown clemency, and many former shogunate leaders and samurai were later given positions of responsibility under the new government.

When the Boshin War began, Japan was already modernizing, following the same course of advancement as that of the industrialized Western nations. Since Western nations, especially the United Kingdom and France, were deeply involved in the country's politics, the installation of Imperial power added more turbulence to the conflict. Over time, the war was romanticized as a "bloodless revolution", as the number of casualties was small relative to the size of Japan's population. However, conflicts soon emerged between the western samurai and the modernists in the Imperial faction, which led to the bloodier Satsuma Rebellion nine years later.

Etymology

Boshin (戊辰) is the designation for the fifth year of a sexagenary cycle in traditional East Asian calendars.[3] Although the war lasted for over a year, Boshin refers to the year that the war started in. The characters 戊辰 can also be read as tsuchinoe-tatsu in Japanese, literally "Elder Brother of Earth-Dragon".[3] In Chinese, it translates as "Yang Earth Dragon", which is associated with that particular year in the sexagenary cycle. The war started in the fourth year of the Keiō era,[4] which also became the first year of the Meiji era in October of that year, and ended in the second year of the Meiji era.[5]

Political background

Early discontent against the shogunate

For the two centuries prior to 1854, Japan had a strict policy of isolationism, restricting all interactions with foreign powers, with the notable exceptions of Korea via Tsushima, Qing China via the Ryukyu Islands, and the Dutch through the trading post of Dejima.[a] In 1854, the United States Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry's expedition opened Japan to global commerce through the implied threat of force, thus initiating rapid development of foreign trade and Westernization. In large part due to the humiliating terms of the unequal treaties, as agreements like those negotiated by Perry are called, the Tokugawa shogunate soon faced internal dissent, which coalesced into a radical movement, the sonnō jōi (meaning "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians").[10]

Emperor Kōmei agreed with such sentiments and, breaking with centuries of Imperial tradition, began to take an active role in matters of state: as opportunities arose, he vehemently protested against the treaties and attempted to interfere in the shogunal succession. His efforts culminated in March 1863 with his "order to expel barbarians". Although the shogunate had no intention of enforcing it, the order nevertheless inspired attacks against the shogunate itself and against foreigners in Japan: the most famous incident was that of the English trader Charles Lennox Richardson, for whose death the Tokugawa government had to pay an indemnity of one hundred thousand British pounds.[11] Other attacks included the shelling of foreign shipping in the port of Shimonoseki.[12]

During 1864, these actions were successfully countered by armed retaliations by foreign powers, such as the British bombardment of Kagoshima and the multinational Shimonoseki campaign. At the same time, the forces of Chōshū Domain, together with rōnin, raised the Hamaguri rebellion trying to seize the city of Kyoto, where the Emperor's court was, but were repelled by shogunate forces under the future shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu. The shogunate further ordered a punitive expedition against Chōshū, the First Chōshū expedition, and obtained Chōshū's submission without actual fighting. At this point the initial resistance among the leadership in Chōshū and the Imperial Court subsided, but over the next year the Tokugawa proved unable to reassert full control over the country as most daimyōs began to ignore orders and questions from the Tokugawa seat of power in Edo.[13]

Foreign military assistance

The Shogun had sought French assistance for training and weaponry since 1865. Léon Roches, French consul to Japan, supported the Shogunal military reform efforts to promote French influence, hoping to make Japan into a dependent client state. This caused the British to send their own military mission to compete with the French.[14]

Despite the bombardment of Kagoshima, the Satsuma Domain had become closer to the British and was pursuing the modernization of its army and navy with their support.[10][12] The Scottish merchant Thomas Blake Glover sold quantities of warships and guns to the southern domains.[b] American and British military experts, usually former officers, may have been directly involved in this military effort.[c] The British ambassador, Harry Smith Parkes, supported the anti-shogunate forces in a drive to establish a legitimate, unified Imperial rule in Japan, and to counter French influence with the shogunate. During that period, southern Japanese leaders such as Saigō Takamori of Satsuma, or Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru of Chōshū cultivated personal connections with British diplomats, notably Ernest Mason Satow.[d] Satsuma domain received British assistance for their naval modernisation, and they became the second largest purchaser of western ships after the Shogunate itself, of which nearly all were British-built. As Satsuma samurai became dominant in the Imperial navy after the war, the navy frequently sought assistance from the British.[19]

In preparation for future conflict, the shogunate also modernized its forces. In line with Parkes's strategy, the British, previously the shogunate's primary foreign partner, proved reluctant to provide assistance.[e] The Tokugawa thus came to rely mainly on French expertise, comforted by the military prestige of Napoleon III at that time, acquired through his successes in the Crimean War and the Second Italian War of Independence.[f]

The shogunate took major steps towards the construction of a modern and powerful military: a navy with a core of eight steam warships had been built over several years and was already the strongest in Asia.[g] In 1865, Japan's first modern naval arsenal was built in Yokosuka by the French engineer Léonce Verny. In January 1867, a French military mission arrived to reorganize the shogunate army and create the Denshūtai elite force, and an order was placed with the US to buy the French-built ironclad warship CSS Stonewall,[22] which had been built for the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Due to the Western powers' declared neutrality, the US refused to release the ship, but once neutrality was lifted, the imperial faction obtained the vessel and employed it in engagements in Hakodate under the name Kōtetsu ("Ironclad").[23]

Coups d'état

Following a coup d'état within Chōshū which returned to power the extremist factions opposed to the shogunate, the shogunate announced its intention to lead a Second Chōshū expedition to punish the renegade domain. This, in turn, prompted Chōshū to form a secret alliance with Satsuma. In the summer of 1866, the shogunate was defeated by Chōshū, leading to a considerable loss of authority. In late 1866, however, first shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi and then Emperor Kōmei died, succeeded by Tokugawa Yoshinobu and Emperor Meiji respectively. These events, in the words of historian Marius Jansen, "made a truce inevitable".[24]

On November 9, 1867, a secret order was created by Satsuma and Chōshū in the name of Emperor Meiji commanding the "slaughtering of the traitorous subject Yoshinobu".[h] Just prior to this, however—and following a proposal from the daimyō of the Tosa Domain—Yoshinobu resigned his post and authority to the emperor, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders.[26] This ended the Tokugawa shogunate.[27][28]

While Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the shogunate government, the Tokugawa family in particular, remained a prominent force in the evolving political order and retained many executive powers.[29][30] Satow speculated that Yoshinobu had agreed to an assembly of daimyōs on the hope that such a body would restore him,[31] a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.[32] Events came to a head on January 3, 1868, when these elements seized the imperial palace in Kyoto, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old Emperor Meiji declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly representing all the domains was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the imperial court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa (under the concept of "just government" (公議政体, kōgiseitai)), Saigō Takamori threatened the assembly into abolishing the title "shōgun" and ordering the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands.[i]

Although he initially agreed to these demands, on January 17, 1868, Yoshinobu declared that he would not be bound by the Restoration proclamation and called for its repeal.[35] On January 24, he decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, which was occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of arsons in Edo, starting with the burning of the outer works of Edo Castle, the main Tokugawa residence. This was blamed on Satsuma rōnin, who on that day attacked a government office. The next day shogunate forces responded by attacking the Edo residence of the daimyō of Satsuma, where many opponents of the shogunate, under Saigo's direction, had been hiding and creating trouble. The residence was burned down, and many opponents killed or later executed.[36]

Weapons and uniforms

The forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were fully modernized with Armstrong Guns, Minié rifles and one Gatling gun.[37][38] The shogunate forces had been slightly lagging in terms of equipment, although the French military mission had recently trained a core elite force.[37] The shōgun also relied on troops supplied by allied domains, which were not necessarily as advanced in terms of military equipment and methods, composing an army that had both modern and outdated elements.[37][39]

Individual guns

Numerous types of more or less modern smoothbore muskets and rifles were imported, from countries as varied as France, Germany, the Netherlands, Britain, and the United States, and coexisted with traditional types such as the tanegashima matchlock.[38] Most shogunate troops used smoothbore muskets, about 200,000 of which had been imported or domestically produced over the years since around 1600.[38]

The first modern firearms were initially imported about 1840 from the Netherlands by the pro-Western reformist Takashima Shūhan.[38][40] The daimyō of Nagaoka Domain, however, an ally of the shōgun, possessed two Gatling guns and several thousand modern rifles.[41][42] The shogunate is known to have placed an order for 30,000 modern Dreyse needle guns in 1866.[43] Napoleon III provided Yoshinobu with 2,000 state-of-the-art Chassepot rifles, which he used to equip his personal guard. Antiquated tanegashima matchlocks are also known to have been used by the shogunate, however.[44]

Imperial troops mainly used Minié rifles, which were much more accurate, lethal, and had a much longer range than the imported smoothbore muskets, although, being also muzzle-loading, they were similarly limited to two shots per minute. Improved breech-loading mechanisms, such as the Snider, developing a rate of about ten shots a minute, are known to have been used by Chōshū troops against the shogunate's Shōgitai regiment at the Battle of Ueno in July 1868. In the second half of the conflict, in the northeast theater, Tosa troops are known to have used American-made Spencer repeating rifles.[44] American-made handguns were also popular, such as the 1863 Smith & Wesson Army No 2, which was imported to Japan by Glover and used by Satsuma forces.[44]

Artillery

For artillery, wooden cannons, only able to fire 3 or 4 shots before bursting, coexisted with state-of-the-art Armstrong guns using explosive shells. Armstrong guns were efficiently used by Satsuma and Saga troops throughout the war. The Shogunate as well as the Imperial side also used native Japanese cannons, with Japan making cannons domestically as far back as 1575.[45]

Warships

In the area of warships also, some of the most recent ironclads such as the Kōtetsu coexisted with older types of steamboats and even traditional sailboats.[21][23] The shogunate initially had the edge in warships, and it had the vision to buy the Kōtetsu. The ship was blocked from delivery by foreign powers on grounds of neutrality once the conflict had started, and was ultimately delivered to the Imperial faction shortly after the Battle of Toba–Fushimi.[23]

Uniforms

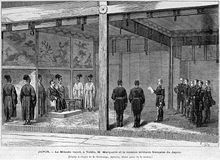

Uniforms were Western-style for modernized troops (usually dark, with variations in the shape of the helmet: tall conical for Satsuma, flat conical for Chōshū, rounded for the shogunate).[46] Officers of the shogunate often wore French and British uniforms. Traditional troops however retained their samurai clothes.[46] Some of the Imperial troops wore peculiar headgear, involving the use of long, colored, "bear" hair. The "red bear" (赤熊, shaguma) wigs indicated officers from Tosa, the "white bear" (白熊, haguma) wigs officers from Chōshū, and the "black bear" (黒熊, koguma) wigs officers from Satsuma.[47]

Status of combatants

Shogunate forces

Sampeitai

The Sampeitai formed a more extensive attempt at modernisation with it being introduced in 1862 by graduates of 2 Samurai academies. The attempt called for the raising of a standing army from the Shogun's personal lands (Tenryo) and the Daimyo under their feudal obligations to provide troops to the Shogun. The army known as the Sampeitai or alternatively the Shinei jobigun was supposed to number 13,625 men with 8,300 infantry (2,000 with rifles) 1,068 cavalry (900 with rifles) 4,890 artillerymen with 48 8 lb field guns and 52 16 lb siege guns and 1,406 officers. The force was to contain half seishi (richer samurai) and half Kashi (poorer Samurai). The recruitment was to be men between 17 and 45 with service terms of 5 years with battalions of 600 companies of 120 and platoons of 40. The daimyo were allowed to substitute manpower with money to purchase firearms and rice to feed the soldiers something the Shoguate desperately needed both of. However, the plan immediately ran into issues as resistance to providing men and money to purchase firearms was met by the shogun. Ironically, the largest provider of men under the new system was the Satsuma domain providing 4,800 infantry, 100 cavalry and 8 guns with 100 men. In 1863 the Shogun allowed the recruitment of commoners but by 1867 this force had only reached 5,900 infantry. In order to augment this force the Shogun raised 5 battalions of Yugekitai. The Shogun also disbanded the city and legation guard units and added them to the Sampeitai adding at least 1,500 men to the army.[48]

Other forces

The Shogunate, aiming to modernise its forces, hired 17 French officers in 1867. These 17 officers trained 900 men who formed the elite Denshutai. The French officers brought with them 3,000 Chassepot rifles and 12 artillery pieces. Three separate military schools were constructed for the infantry, artillery and cavalry with limited engineer instruction, they also introduced carbine and lance cavalry to the force. It was intended for the 900 men of the Denshutai to be dispersed amongst the myriad of Shogunate armies to train and re-organise them though this did not occur due to the outbreak of hostilities.[49]

The Shogun additionally possessed 302 Shinsengumi police forces who were intensely loyal to the Shogunate. The Shogunate navy also contained 3,000 sailors who acted as infantry on Hokkaido towards the end of the war.[49]

Imperial forces

Satsuma

The Satsuma domain in 1840 contained 25,000 samurai and being more open to the world at large underwent a more rapid process of modernisation than the Shogunate. In 1854 a foundry was already founded for firearms production, soon joined by an artillery foundry and three ammunition plants. The Anglo-Satsuma war of 1863 gave the Satsuma officials a further incentive for more extensive military reforms due to the poor military performance of its forces. The Daimyo therefore hired several French officers and began enrolling peasants into the military.[50]

Choshu

The Choshu domain in 1840 contained 11,000 samurai and was also more amenable to reform, and more ambitious than Satsuma in reform and the recruitment of peasantry with the formation of the 300 strong Kihetai, a mixed formation of samurai, townsmen, and peasants, with ronin officers with tough discipline and western uniforms. A second and third company was raised increasing its strength to 900 men. The usage of gunboat diplomacy brought in many volunteers and another 980 men were formed in several shotai or auxiliary militia, with 60 units in total by 1865. These shotai were added to the Choshu military and given modern weaponry by 1868.[50]

By 1868 there were 150 shotai and they were regularised and when added to the regular domain army contained a total of 36 infantry battalions amounting to 14,400 men which formed the core of the Pro-Imperial Army when war broke out.[51]

Imperial military

In April 1868 Emperor Meiji himself called for the dispatch of 60 men per 10,000 koku (150 kg of rice, the amount needed for a man for one year) produced in his domain, of the 60 man drafts one-sixth were to be sent to Kyoto to form an Imperial army and the remaining 50 to garrison the Daimyo's domain.[51]

Opening conflicts

On January 27, 1868, shogunate forces attacked the forces of Chōshū and Satsuma, clashing near Toba and Fushimi, at the southern entrance to Kyoto in the Battle of Toba–Fushimi. Some parts of the 15,000-strong shogunate forces had been trained by French military advisers. Among their numbers during this battle were the noted Shinsengumi.[52][44] The forces of Chōshū and Satsuma were outnumbered 3:1 but fully modernized with Armstrong howitzers, Minié rifles and a few Gatling guns.[44]

After an inconclusive start,[j] an Imperial banner was presented to the defending troops on the second day, and a relative of the Emperor, Ninnajinomiya Yoshiaki, was named nominal commander in chief, making the forces officially an imperial army (官軍, kangun).[k] Moreover, convinced by courtiers, several local daimyōs, up to this point faithful to the shōgun, started to defect to the side of the Imperial Court. These included the daimyōs of Yodo and Tsu in February, tilting the military balance in favour of the Imperial side.[34]

After the defections, Yoshinobu, apparently distressed by the imperial approval given to the actions of Satsuma and Chōshū, fled Osaka aboard the Japanese battleship Kaiyō Maru, withdrawing to Edo. Demoralized by his flight and by the betrayal by Yodo and Tsu, shogunate forces retreated, resulting in an Imperial victory, although it is often considered the shogunate forces should have won the encounter.[l] Osaka Castle was soon invested on March 1 (February 8 in the Tenpō calendar), putting an end to the battle.[56]

The day after the battle of Toba–Fushimi commenced, the naval Battle of Awa took place between the shogunate and elements of the Satsuma navy in Awa Bay near Osaka. This was Japan's second engagement between two modern navies.[17] The battle, although small in scale, ended with a victory for the shogunate.[57]

On the diplomatic front, the ministers of foreign nations, gathered in the open harbour of Hyōgo (present day Kobe) in early February, issued a declaration according to which the shogunate was still considered the only rightful government in Japan, giving hope to Tokugawa Yoshinobu that foreign nations (especially France) might consider an intervention in his favour. A few days later however an Imperial delegation visited the ministers declaring that the shogunate was abolished, that harbours would be open in accordance with International treaties, and that foreigners would be protected. The ministers finally decided to recognize the new government.[58]

The rise of anti-foreign sentiment nonetheless led to several attacks on foreigners in the following months. Eleven French sailors from the corvette Dupleix were killed by samurai of Tosa in the Sakai incident on March 8, 1868. Fifteen days later, Sir Harry Parkes, the British ambassador, was attacked by a group of samurai in a street of Kyoto.[59]

Surrender of Edo

Beginning in February, with the help of the French ambassador Léon Roches, a plan was formulated to stop the Imperial Court's advance at Odawara, the last strategic entry point to Edo, but Yoshinobu decided against the plan. Shocked, Léon Roches resigned from his position. In early March, under the influence of the British minister Harry Parkes, foreign nations signed a strict neutrality agreement, according to which they could not intervene or provide military supplies to either side until the resolution of the conflict.[60]

Saigō Takamori led the victorious imperial forces north and east through Japan, winning the Battle of Kōshū-Katsunuma. He eventually surrounded Edo in May 1868, leading to its unconditional defeat after Katsu Kaishū, the shōgun's Army Minister, negotiated the surrender.[61] Some groups continued to resist after this surrender but were defeated in the Battle of Ueno on July 4, 1868.[39][62]

Meanwhile, the leader of the shōgun's navy, Enomoto Takeaki, refused to surrender all his ships. He remitted just four ships, among them the Fujiyama, but he then escaped north with the remnants of the shōgun's navy (eight steam warships: Kaiten, Banryū, Chiyodagata, Chōgei, Kaiyō Maru, Kanrin Maru, Mikaho and Shinsoku), and 2,000 personnel, in the hope of staging a counter-attack together with the northern daimyōs. He was accompanied by a handful of French military advisers, notably Jules Brunet, who had formally resigned from the French Army to accompany the rebels.[16]

Resistance of the Northern Coalition

After Yoshinobu's surrender, he was placed under house arrest, and stripped of all titles, land and power. He was later released, when he demonstrated no further interest and ambition in national affairs. He retired to Shizuoka, the place to which his ancestor Tokugawa Ieyasu had also retired. Most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule, but a core of domains in the North, supporting the Aizu clan, continued the resistance.[63][64] In May, several northern daimyōs formed an Alliance to fight Imperial troops, the coalition of northern domains composed primarily of forces from the domains of Sendai, Yonezawa, Aizu, Shōnai and Nagaoka Domain, with a total of 50,000 troops.[65] Apart from those core domains, most of the northern domains were part of the alliance.[65]

In May 1868, the daimyō of Nagaoka inflicted high losses on the Imperial troops in the Battle of Hokuetsu, but his castle ultimately fell on May 19. Imperial troops continued to progress north, defeating the Shinsengumi at the Battle of Bonari Pass, which opened the way for their attack on the castle of Aizuwakamatsu in the Battle of Aizu in October 1868, thus making the position in Sendai untenable.[66]

Enomoto's fleet reached Sendai harbour on August 26. Although the Northern Coalition was numerous, it was poorly equipped, and relied on traditional fighting methods. Modern armament was scarce, and last-minute efforts were made to build cannons made of wood and reinforced with roping, firing stone projectiles. Such cannons, installed on defensive structures, could only fire four or five projectiles before bursting.[m] On the other hand, the daimyō of Nagaoka managed to procure two of the three Gatling guns in Japan and 2,000 modern French rifles from the German weapons dealer Henry Schnell.[41]

The coalition crumbled, and on October 12, 1868, the fleet left Sendai for Hokkaidō, after having acquired two more ships (Oe and Hōō, previously borrowed by Sendai from the shogunate), and about 1,000 more troops: remaining shogunate troops under Ōtori Keisuke, Shinsengumi troops under Hijikata Toshizō, the guerilla corps (yugekitai) under Hitomi Katsutarō, as well as several more French advisers (Fortant, Garde, Marlin, Bouffier).[16]

On October 26, Edo was renamed Tokyo, and the Meiji period officially started. Aizu was besieged starting that month, leading to the mass suicide of the Byakkotai (White Tiger Corps) young warriors.[68] After a protracted month-long battle, Aizu finally admitted defeat on November 6.[69]

Hokkaidō campaign

Creation of the Ezo Republic

Following defeat on Honshū, Enomoto Takeaki fled to Hokkaidō with the remnants of the navy and his handful of French advisers. Together they organized a government, with the objective of establishing an independent island nation dedicated to the development of Hokkaidō. They formally established the Republic of Ezo on the American model, Japan's only ever republic, and Enomoto was elected as president, with a large majority. The republic tried to reach out to foreign legations present in Hakodate, such as the Americans, French, and Russians, but was not able to garner any international recognition or support. Enomoto offered to confer the territory to the Tokugawa shōgun under Imperial rule, but his proposal was declined by the Imperial Governing Council.[n]

During the winter, they fortified their defenses around the southern peninsula of Hakodate, with the new fortress of Goryōkaku at the center. The troops were organized under a Franco-Japanese command, the commander-in-chief Ōtori Keisuke being seconded by the French captain Jules Brunet, and divided between four brigades. Each of these was commanded by a French non-commissioned officer (Fortant, Marlin, Cazeneuve, Bouffier), and were themselves divided into eight half-brigades, each under Japanese command.[71]

Final losses and surrender

The Imperial Navy reached the harbour of Miyako on March 20, but anticipating the arrival of the Imperial ships, the Ezo rebels organized a daring plan to seize the Kōtetsu. Led by Shinsengumi commander Hijikata Toshizō, three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. The battle ended in failure for the Tokugawa side, owing to bad weather, engine trouble and the decisive use of a Gatling gun by Imperial troops against samurai boarding parties.[o]

Imperial forces soon consolidated their hold on mainland Japan, and, in April 1869, dispatched a fleet and an infantry force of 7,000 to Ezo, starting the Battle of Hakodate. The Imperial forces progressed swiftly and won the naval engagement at Hakodate Bay, Japan's first large-scale naval battle between modern navies, and the fortress of Goryōkaku was surrounded. Seeing the situation had become desperate, the French advisers escaped to a French ship stationed in Hakodate Bay – Coëtlogon, under the command of Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars – from where they were shipped back to Yokohama and then France. The Japanese requested that the French advisers be given judgement in France; however, due to popular support in France for their actions, the former French advisers were not punished for their actions.[72]

Invited to surrender, Enomoto at first refused, and sent the Naval Codes he had brought back from Holland to the general of the Imperial troops, Kuroda Kiyotaka, to prevent their loss. Ōtori Keisuke convinced him to surrender, telling him that deciding to live through defeat is the truly courageous way: "Dying is easy; you can do that anytime."[73] Enomoto surrendered on June 27, 1869, accepting Emperor Meiji's rule, and the Ezo Republic ceased to exist.[74]

Aftermath

Of the approximately 120,000 men mobilized over the course of the conflict, about 8,200 were killed and more than 5,000 were wounded.[2] Following victory, the new government proceeded with unifying the country under a single, legitimate and powerful rule by the Imperial Court. The emperor's residence was effectively transferred from Kyoto to Edo at the end of 1868, and the city renamed to Tokyo. The military and political power of the domains was progressively eliminated, and the domains themselves were transformed in 1871 into prefectures, whose governors were appointed by the emperor.[75][p]

A major reform was the effective expropriation and abolition of the samurai class, allowing many samurai to change into administrative or entrepreneurial positions, but forcing many others into poverty.[q] The southern domains of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa, having played a decisive role in the victory, occupied most of the key posts in government for several decades following the conflict, a situation sometimes called the "Meiji oligarchy" and formalized with the institution of the genrō.[r] In 1869, the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo was built in honor of the victims of the Boshin War.[77]

Some leading partisans of the former shōgun were imprisoned, but narrowly escaped execution. This clemency derives from the insistence of Saigō Takamori and Iwakura Tomomi, although much weight was placed on the advice of Parkes, the British envoy. He had urged Saigō, in the words of Ernest Satow, "that severity towards Keiki [Yoshinobu] or his supporters, especially in the way of personal punishment, would injure the reputation of the new government in the opinion of European Powers".[78] After two or three years of imprisonment, most of them were called to serve the new government, and several pursued brilliant careers. Enomoto Takeaki, for instance, would later serve as an envoy to Russia and China and as the education minister.[16][79][80][81]

The Imperial side did not pursue its objective of expelling foreign interests from Japan, but instead shifted to a more progressive policy aiming at the continued modernization of the country and the renegotiation of unequal treaties with foreign powers, later under the "rich country, strong army" (富国強兵, fukoku kyōhei) motto.[82]

The shift in stance towards foreigners came during the early days of the civil war: on April 8, 1868, new signboards were erected in Kyoto (and later throughout the country) that specifically repudiated violence against foreigners.[83] During the course of the conflict, Emperor Meiji personally received European envoys, first in Kyoto, then later in Osaka and Tokyo.[84] Also unprecedented was Emperor Meiji's reception of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in Tokyo, "as his equal in point of blood".[85]

Although the early Meiji era witnessed a warming of relations between the Imperial Court and foreign powers, relations with France temporarily soured due to the initial support by France for the shōgun. Soon, however, a second military mission was invited to Japan in 1874, and a third one in 1884. A high level of interaction resumed around 1886, when France helped build the Imperial Japanese Navy's first large-scale modern fleet, under the direction of naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin.[86] The modernization of the country had started during the last years of the shogunate, and the Meiji government ultimately adopted the same policy.[87][88]

Upon his coronation, Meiji issued his Charter Oath, calling for deliberative assemblies, promising increased opportunities for the common people, abolishing the "evil customs of the past", and seeking knowledge throughout the world "to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule".[89][s] The reforms culminated in the 1889 issuance of the Meiji Constitution. However, despite the support given to the Imperial Court by samurai, many of the early Meiji reforms were seen as detrimental to their interests. The creation of a conscript army made of commoners, as well as the loss of hereditary prestige and stipends, antagonized many former samurai.[92] Tensions ran particularly high in the south, leading to the 1874 Saga Rebellion, and a rebellion in Chōshū in 1876. Former samurai in Satsuma, led by Saigō Takamori, who had left government over foreign policy differences, started the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877. Fighting for the maintenance of the samurai class and a more virtuous government, their slogan was "new government, high morality" (新政厚徳, shinsei kōtoku). It ended with a heroic but total defeat at the Battle of Shiroyama.[93][t]

The Japan that followed

On the eve of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), those in the political and military leadership were individuals who had fought in the Boshin War. Well aware of what happened to Matsudaira Katamori—in other words, the fate that awaits a defeated nation—they were considering peace negotiations even before the war began. They chose U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt as a mediator between Japan and Russia and sent Kaneko Kentaro to the United States.[95] On the other hand, the politicians and military leaders on the eve of World War II (1939–45) were individuals with no knowledge of the Boshin War (except for Saionji Kinmochi). When faced with the Hull note, they believed war was inevitable and launched the attack on Pearl Harbor without considering the long-term consequences, ultimately leading to a devastating defeat. The difference in caliber between leaders in the Meiji and Showa eras is often mentioned in the novels of Ryōtarō Shiba.[96]

Later depictions

In modern summaries, the Meiji Restoration is often described as a "bloodless revolution" leading to the sudden modernization of Japan. The facts of the Boshin War, however, clearly show that the conflict was quite violent: about 120,000 troops were mobilized altogether with roughly 3,500 known casualties during open hostilities but much more during terrorist attacks.[97] Although traditional weapons and techniques were used, both sides employed some of the most modern armaments and fighting techniques of the period, including the ironclad warship, Gatling guns, and fighting techniques learned from Western military advisers.

Such Japanese depictions include numerous dramatizations, spanning many genres. Notably, Jirō Asada wrote a four-volume novel of the account, Mibu Gishi-den.[98] A film adaptation of Asada's work, directed by Yōjirō Takita, is known as When the Last Sword Is Drawn.[98] A ten-hour 2002 television jidaigeki based on the same novel starred Ken Watanabe.[99] A Japanese Manga Series, Rurouni Kenshin, by Nobuhiro Watsuki, notably sets place in the war, and the aftermath.

Western interpretations include the 2003 American film The Last Samurai directed by Edward Zwick, which combines into a single narrative historical situations belonging both to the Boshin War, the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion, and other similar uprisings of ex-samurai during the early Meiji period.[100] The elements of the movie pertaining to the early modernization of Japan's military forces as well as the direct involvement of foreign (mostly French) forces relate to the Boshin War and the few years leading to it.[100] However, the suicidal stand of traditionalist samurai forces led by Saigō Takamori against the modernized Imperial army relate to the much later Satsuma Rebellion.[101]

The main campaign in the 2012 expansion to Creative Assembly's game Total War: Shogun 2: Fall of the Samurai depicts the Boshin War.[102] Players can choose from various historical clans, such as the Imperial Satsuma or the shogunate Aizu.[102]

See also

Notes

- ^ Thanks to the interaction with the Dutch, the study of Western science continued during this period under the name of rangaku, allowing Japan to study and follow most of the steps of the Scientific and Industrial Revolution. Jansen discusses the vibrancy of Edo period rangaku,[6] and notes the competition in the early Meiji period for foreign experts and rangaku scholars.[7] Timon Screech discusses this in two of his papers.[8][9]

- ^ As early as 1865, Thomas Blake Glover sold 7,500 Minié rifles to the Chōshū clan, allowing it to become totally modernized. Nakaoka Shintaro a few months later remarked that "in every way the forces of the han have been renewed; only companies of rifle and cannon exist, and the rifles are Minies, the cannon breech loaders using shells."[15]

- ^ This is a claim made by Jules Brunet in a letter to Napoleon III: "I must signal to the Emperor the presence of numerous American and British officers, retired or on leave, in this party [of the southern daimyōs] which is hostile to French interests. The presence of Western leaders among our enemies may jeopardize my success from a political standpoint, but nobody can stop me from reporting from this campaign information Your Majesty will without a doubt find interesting." Original quotation (French): "Je dois signaler à l'Empereur la présence de nombreux officers américains et anglais, hors cadre et en congé, dans ce parti hostile aux intérêts français. La présence de ces chefs occidentaux chez nos adversaires peut m'empêcher peut-être de réussir au point de vue politique, mais nul ne pourra m'empêcher de rapporter de cette campagne des renseignements que Votre Majesté trouvera sans doute intéressants."[16] As an example, the English Lieutenant Horse is known to have been a gunnery instructor for the Saga domain during the Bakumatsu period.[17]

- ^ These encounters are described in Satow's 1869 A Diplomat in Japan, where he describes Saigō as a man with "an eye that sparkled like a big black diamond".[18]

- ^ For example, An 1864 request to Sir Rutherford Alcock to supply British military experts from the 1,500 men stationed at Yokohama went unanswered, and when Takenaka Shibata visited the United Kingdom and France, in September 1865, requesting assistance, only the latter was forthcoming.[20]

- ^ Following the deal with France, the French ambassador in Japan Leon Roches, trying not to alienate the United Kingdom, arranged for the shōgun to ask for a British navy mission which arrived sometime after the French military mission of 1867.[20]

- ^ There is debate as to the authenticity of the order, due to its violent language and the fact that, despite using the imperial pronoun (朕, chin), it did not bear Meiji's signature.[25]

- ^ During a recess, Saigō, who had his troops outside, "remarked that it would take only one short sword to settle the discussion".[33] Original quotation Japanese was "短刀一本あればかたづくことだ".[34] The specific word used for "dagger" was "tantō".[34]

- ^ Saigō, while excited at the beginning of combat, had planned for the evacuation of the emperor from Kyoto if the situation demanded it.[53]

- ^ The red and white pennant had been conceived and designed by Okubo Toshimichi and Iwakura Tomomi, among others. It was in effect a forgery, as was the imperial order to deploy it among the defending troops. Prince Yoshiaki, was also given a special sword and appointed "great general, conqueror of the east", and the shogunal forces opposing Yoshiaki were branded "enemies of the court".[54]

- ^ "Militarily, the Tokugawa were vastly superior. They had between three to five times more soldiers and held Osaka Castle as a base, they could count on the forces from Edo modernized by the French, and they had the most powerful fleet of East Asia at hand in Osaka Bay. In a regular fight, the Imperial side had to lose. Saigō Takamori too, anticipating defeat had planned to move the Emperor to the Chūgoku mountains and was preparing for guerilla warfare."[55]

- ^ A detailed presentation of artifacts from that phase of the war is visible at the Sendai City Museum, in Sendai, Japan.[67]

- ^ In a letter of Enomoto to the Imperial Governing Council: "We pray that this portion of the Empire may be conferred upon our late lord, Tokugawa Kamenosuke; and in that case, we shall repay your beneficence by our faithful guardianship of the northern gate."[70]

- ^ Collache was on board one of the ships that participated to the attack. He had to wreck his ship and flee overland, until he surrendered with his colleagues and was transferred to a prison in Tokyo. He ultimately returned to France safely to tell his story.[72]

- ^ Many daimyōs were appointed as the first governors, and subsequently given peerages and large pensions. Over the following years, the three hundred domains were reduced to fifty prefectures.[76]

- ^ Most legal distinctions between samurai and ordinary subjects were soon abolished, and the traditional rice stipends paid to samurai were first converted into cash stipends, and these were later converted at a steep discount to government bonds.[75]

- ^ For example Saigō Takamori, Okubo Toshimichi, and Tōgō Heihachirō all came from Satsuma.[17]

- ^ Jansen discusses political developments during and relating to the course of the war.[90] Keene discusses the Charter Oath and signboard decrees.[91]

- ^ Saigō himself professed continued loyalty to Meiji and wore his Imperial Army uniform throughout the conflict. He committed suicide before the final charge of the rebellion, and was posthumously pardoned by the emperor in subsequent years.[94]

- ^ The shogunate leaders are labeled from left to right, Enomoto (Kinjirō) Takeaki, Ōtori Keisuke, Matsudaira Tarō. The samurai in yellow garment is Hijikata Toshizō.

- ^ The "Red bear" (赤熊, Shaguma) wigs indicate soldiers from Tosa, the "White bear" (白熊, Haguma) wigs for Chōshū, and the "Black bear" (黒熊, Koguma) wigs for Satsuma.[47]

References

- ^ Cortazzi (1985)

- ^ a b Huffman (1997).

- ^ a b 戊辰(ぼしん) の意味 [Boshin (Boshin) definition] (in Japanese). NTT Resonant, Inc. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Nussbaum, p. 505.

- ^ Nussbaum, p. 624.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 210–215.

- ^ Jansen, p. 346.

- ^ Screech (1998).

- ^ Screech (2006).

- ^ a b Hagiwara, p. 34.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 314–315.

- ^ a b Hagiwara, p. 35.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 303–305.

- ^ Mark Ravina (2017). To Stand with the Nations of the World: Japan's Meiji Restoration in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 9780195327717.

- ^ Brown (1993).

- ^ a b c d Polak, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Togo (1993).

- ^ Satow, p. 181.

- ^ Henny, et al, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Polak, pp. 53–55.

- ^ "CSS Stonewall (1865)". Naval Historical Center. 9 February 2003. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Keene, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Jansen, p. 307.

- ^ Keene, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Satow, p. 282.

- ^ Keene, p. 116.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Keene, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Satow, p. 283.

- ^ Satow, p. 285.

- ^ Satow, p. 286.

- ^ Keene, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Hagiwara, p. 42.

- ^ Keene, p. 124.

- ^ Keene, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Esposito, pp. 23–34.

- ^ a b c d Esposito, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Ravina (2005), pp. 149–160.

- ^ Jansen, p. 288.

- ^ a b Vaporis, p. 35.

- ^ Esposito, p. 10.

- ^ Feuss, Harald (2020). The Meiji Restoration. Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 9781108478052.

- ^ a b c d e Ryozen Museum of History exhibit.[clarification needed]

- ^ Perrin, p. 19.

- ^ a b Esposito, pp. 17–23.

- ^ a b Gonick, p. 25.

- ^ Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868–1877 : the Boshin War & Satsuma Rebellion. Giuseppe Rava. Oxford. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-1-4728-3706-6. OCLC 1130012340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868-1877 : the Boshin War & Satsuma Rebellion. Giuseppe Rava. Oxford. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-1-4728-3706-6. OCLC 1130012340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868-1877 : the Boshin War & Satsuma Rebellion. Giuseppe Rava. Oxford. pp. 46–50. ISBN 978-1-4728-3706-6. OCLC 1130012340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868–1877 : the Boshin War & Satsuma Rebellion. Giuseppe Rava. Oxford. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-1-4728-3706-6. OCLC 1130012340.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vaporis, p. 33.

- ^ Keene, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Keene, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Hagiwara, p. 43. Translation from the Japanese original.

- ^ Hagiwara, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Tucker, p. 274.

- ^ Polak, p. 75.

- ^ "Sommaire". Le Monde illustré (in French). No. 583. 13 June 1868. p. 1. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Polak, p. 77.

- ^ Hagiwara, p. 46.

- ^ Perez, p. 32.

- ^ Bolitho, p. 246.

- ^ Black, p. 214.

- ^ a b Polak, pp. 79–91.

- ^ Turnbull, pp. 153–58.

- ^ 「旬の常設展2020夏」のご案内 [Up-to-date Permanent Exhibits Summer 2020 Information] (in Japanese). Sendai City Museum. Retrieved 20 August 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Watanabe, Minako (October 2002). "The Byakkotai and the Boshin War". Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Turnbull, p. 11.

- ^ Black, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Polak, pp. 85–89.

- ^ a b Collache (1874).

- ^ Perez, p. 84.

- ^ Onodera, p. 196.

- ^ a b Gordon, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 348–349.

- ^ "Koizumi shrine visit stokes anger". BBC News. 15 August 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Keene, p. 143.

- ^ 歴代文部科学大臣 [Historical list of Ministers of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology] (in Japanese). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Iguro, p. 559.

- ^ Keene, pp. 204, 399, 434.

- ^ Keene, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Keene, p. 142.

- ^ Keene, pp. 143–144, 165.

- ^ Parkes, quoted in Keene, pp. 183–187. Emphasis in the original.

- ^ Evans and Peattie, p. 15.

- ^ Takada (1990).

- ^ Furukawa (1995).

- ^ Jansen, p. 338.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 337–343.

- ^ Keene, pp. 138–142.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 367–368.

- ^ Hagiwara, pp. 94–120.

- ^ Jansen, pp. 369–370.

- ^ "伊藤博文は、金子にルーズベルトとの旧交を温めさせ、日露戦争を早期に終わらせるよう斡旋してくれることを、ルーズベルトに依頼する任務を託した". President. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "司馬遼太郎氏の歴史観は、明治期の戦争を肯定的に、昭和期の戦争を否定的に捉えているのがその特徴". The Matsushita Institute of Government and Management. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Hagiwara, p. 50.

- ^ a b Galloway (2012).

- ^ 時代劇☆壬生義士伝 [Jidaigeki: Mibu Gishiden] (in Japanese). TV Tokyo. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b Mclaughlin, William (11 November 2016). "The Last Samurai: The True History Behind The Film". War History Online. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Ravina (2010).

- ^ a b Senior, Tom (16 March 2012). "Shogun 2: Fall of the Samurai review". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

Works cited

- Banno, Junji (2014). Japan's Modern History, 1857–1937: A New Political Narrative. Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies. London/New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138775176.

- Bolitho, Harold (1974). Treasures among Men: The Fudai Daimyo in Tokugawa Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-01655-0. OCLC 185685588.

- Black, John R. (1881). Young Japan: Yokohama and Yedo, Vol. II. London: Trubner & Co.

- Brown, Sidney DeVere (Summer 1993). "Nagasaki in the Meiji Restoration: Choshu loyalists and British arms merchants". Crossroads: A Journal of Nagasaki History and Culture (1): 1–18. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- Collache, Eugène (1874). "Une aventure au Japon". Le Tour du Monde (in French). No. 77. pp. 49–64.

- Cortazzi, Hugh (1985). Dr. Willis in Japan, 1862–1877: A British Medical Pioneer (1st ed.). London: Athlone Press. ISBN 9780485112641.

- Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868–1877: The Boshin War and Satsuma Rebellion. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-3708-0.

- Evans, David; Mark Peattie (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Furukawa, Hisao (December 1995). "Meiji Japan's Encounter with Modernization" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 33 (3). Kyoto, Japan: Center for Southeast Asian Studies: 497–518.

- Galloway, Patrick (2012). Berra, John (ed.). Directory of World Cinema: Japan 2. Bristol, England: Intellect Books. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1841505510.

- Gonick, Gloria (2002). Matsuri! Japanese Festival Arts. University of California Museum. ISBN 0930741919.

- Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-511060-9.

- Hagiwara, Kōichi (2004). 図説 西郷隆盛と大久保利通 [Illustrated life of Saigō Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi] (in Japanese). Kawade Shobō Shinsha. ISBN 4-309-76041-4.

- Henny, Sue; Lehmann, Jean-Pierre (2013). Themes and Theories in Modern Japanese History: Essays in Memory of Richard Storry. A&C Black. ISBN 9781780939711.

- Huffman, James L. (1997). Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 9780815325253.

- Iguro, Yatarō (1968). 榎本武揚伝 [The Biography of Enomoto Takeaki] (in Japanese). ゆまに書房.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard. ISBN 978-0-674-00334-7. OCLC 44090600.

- Keene, Donald (2005). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. Columbia. ISBN 0-231-12340-X. OCLC 46731178.

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Belknap Press / Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674017536.

- Okada, Shin'ichi; Tanaka, Akira; Polak, Christian; Konno, Tetsuya; Tsunabuchi, Kenjō (1988). 函館の幕末・維新 [End of the Bakufu and Restoration in Hakodate] (in Japanese). 中央公論社. ISBN 4-12-001699-4.

- Onodera, Eikō (December 2004). 戊辰南北戦争と東北政権 [The Boshin Civil War and Tōhoko Political Power] (in Japanese). Kitanosha. ISBN 978-4907726256.

- Perez, Louis G., ed. (2013). Japan at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-741-3. LCCN 2012030062.

- Polak, Christian (2001). 絹と光: 知られざる日仏交流100年の歴史 (江戶時代-1950年代) [Silk and Light: 100-year history of unconscious French-Japanese cultural exchange (Edo Period – 1950)] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Hachette / Fujin Gahōsha. ISBN 4-573-06210-6. OCLC 50875162.

- Ravina, Mark (2005). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-70537-3.

- Ravina, Mark J. (August 2010). "The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigō Takamori: Samurai, "Seppuku", and the Politics of Legend". The Journal of Asian Studies. 69 (3): 691–721. doi:10.1017/S0021911810001518. JSTOR 40929189. S2CID 155001706.

- Satow, Ernest (1968) [1921]. A Diplomat in Japan. Tokyo: Oxford.

- Screech, Timon (1998). 江戸の思想空間 [The Intellectual World of Edo] (in Japanese). Translated by Murayama, Kazuhiro. Seidosha. ISBN 4-7917-5690-8.

- Screech, Timon (2006). "The Technology of Edo". In Suzuki, Kazuyoshi (ed.). 見て楽しむ江戸のテクノロジー [The Enjoyable Observance of Edo Technology] (in Japanese). Suken Shuppan. ISBN 4-410-13886-3.

- Takada, Makoto (1990). "The development of Japanese society and the modernization of Japanese during the Meiji Restoration". In Coulmas, Florian (ed.). Language Adaptation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 104–115. ISBN 0521362555.

- Togo, Heihachirō (March 1993). 図説東郷平八郎、目で見る明治の海軍 [Togo Heihachirō in Images: Illustrated Meiji Navy] (in Japanese). 東郷神社・東郷会. JPNO 94056122.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2017). The Roots and Consequences of Civil Wars and Revolutions: Conflicts that Changed World History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-4294-8.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2008). The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War. Clarendon, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4805309568.

- Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (2019). Samurai: An Encyclopedia of Japan's Cultured Warriors. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1440842702.

Further reading

- Jansen, Marius B. (1999). "Chapter 5: The Meiji Restoration". The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-65728-8.

External links

Media related to Boshin War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Boshin War at Wikimedia Commons- The Boshin War (in Japanese)

- The Battle of Ezo (in Japanese)

- National Archives of Japan: Boshinshoyo Kinki oyobi Gunki Shinzu, precise reproduction of Imperial Standard and the colors used by Government Army during Boshin War (1868)