Battle of White Sulphur Springs

| Battle of White Sulphur Springs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Greenbrier County, West Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 1,300 | ~ 2,300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 218 (26 killed, 125 wounded, 67 captured) | 162 (20 killed, 129 wounded, 13 missing) | ||||||

The Battle of White Sulphur Springs, also known as the Battle of Rocky Gap or the Battle of Dry Creek, occurred in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, on August 26 and 27, 1863, during the American Civil War. A Confederate Army force commanded by Colonel George S. Patton defeated a Union brigade commanded by Brigadier General William W. Averell. West Virginia had been a state for only a few months, and its citizens along the state's southern border were divided in loyalty to the Union and Confederate causes. Many of the fighters on both sides were West Virginians, and some were from the counties close to the site of the battle.

The battle was a turning point for the first of three mounted expeditions into Confederate-held territory led by Averell in the latter half of 1863. The expedition had multiple targets, including a saltpeter works, a Confederate cavalry force in Pocahontas County, West Virginia, and the law books from the law library of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals in Lewisburg, West Virginia. Confederate leaders feared Averell's mission was to destroy sections of a railroad—either the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad or the Virginia Central Railroad. Both railroads were important to the Confederacy for moving materials and men, and one served a lead mine used for the army's bullets. Defending against Averell was a force of four Virginia regiments and an artillery battery at Lewisburg, temporarily commanded by Patton in the absence of Brigadier General John Echols, who was over 200 miles (320 km) away in Richmond.

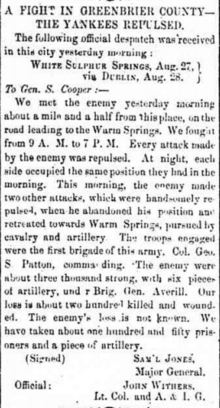

Patton's Confederate force stopped Averell's Union brigade near White Sulphur Springs—about 10 miles (16 km) east of Lewisburg. Both sides made numerous charges in the battle, but neither gained much ground. The Union force was prevented from reaching its objective in Lewisburg, and was forced to make a difficult retreat north while being pursued by Confederate forces. The Confederate victory proved that Patton could ably command a large force of over 2,000 men, and (unknown to the Confederacy) saved the law library in Lewisburg. Confederate leaders mistakenly believed they had saved the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad and a lead mine. Averell achieved the first two of his three objectives, and his newly-mounted men also gained valuable experience in cavalry tactics in the mountains of West Virginia. The books from the law library were never captured, and they were eventually moved to Richmond, Virginia. As of 2011, the battlefield has not been preserved. Three small monuments are side by side near a fast food restaurant, and across the street on the other side of a small creek is a historical marker that calls the clash the "Dry Creek Battle".

Background and plans

West Virginia

Between December 20, 1860, and February 1, 1861, seven southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America.[Note 1] Fighting began on April 12, 1861, when American troops were attacked at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, and this is considered the beginning of the American Civil War. Four additional states, including Virginia, seceded during the next three months.[2] On April 17, 1861, representatives of the Commonwealth of Virginia held the Virginia Secession Convention, and passed an Ordinance of Secession that declared secession from the United States. The ordinance was ratified by popular referendum on May 23, and Virginia later joined the Confederate States of America.[3] In June of that year, residents of the northwest part of the state who remained loyal to the United States met at the Second Wheeling Convention. On June 19, they approved a plan to establish an alternative loyal state government that would be located in Wheeling.[3] Virginians loyal to the United States declared their own statehood on October 24, 1861, and it officially became the state of West Virginia on June 20, 1863.[4]

The new state had rugged terrain, few good roads, few settlements, and far fewer financial resources than neighboring states.[5] Although Union Major General George B. McClellan occupied much of northwestern Virginia in 1861 in the Western Virginia campaign, Union troops in West Virginia were reduced in 1862 when many were sent east.[6] This enabled Confederate Major General William W. Loring to drive Union troops in the Kanawha Valley and Charleston back to the Ohio River.[7] After the Battle of Charleston, Confederate occupation of the town did not last long, but regular Confederate Army soldiers still operated within the state of West Virginia in 1863. Not all residents were loyal to the Union; bushwhackers and Partisan rangers practiced guerrilla warfare tactics to gain control of the state.[8] Many of the people from the mountains were pro-Union, while the majority in the large valleys were pro-Confederate.[9] Approximately twenty to twenty-two thousand West Virginians fought on each side of the conflict.[10] Lewisburg, located in West Virginia near the border with Virginia, supported the Confederacy.[Note 2]

Railroads

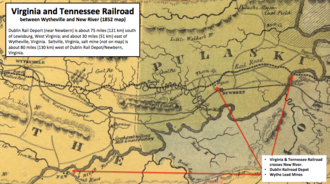

About 20 percent of the Confederacy's railroad network was in Virginia, where the Confederate capital city of Richmond had railroads entering and exiting from the north, east, south, and west.[12] Among Virginia's railroads, the 200-mile (320 km) Virginia Central Railroad ran from Richmond deep into the western side of the upper Shenandoah Valley. It was used to shuttle troops and bring raw materials from the Valley to eastern population centers such as Richmond.[13] Another important railway was the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, which was located close to West Virginia's southern border. This railroad was used by the Confederacy for moving troops and supplies between those states, and connected to more railroads at Lynchburg, Virginia and Bristol, Tennessee. It had telegraph wires along its line, and important salt and lead mines were located along its route near Wytheville, Virginia.[14] The lead mine was the source for an estimated one third of the lead used by the Confederacy to produce bullets for its armies.[15] A mid-July 1863 raid by Union cavalry and mounted infantry, known as the Wytheville Raid or Toland's Raid, failed to inflict permanent damage to the railroad and did not reach the mines.[16]

William W. Averell

Brigadier General William W. Averell was a West Point graduate, excellent horseman, and had experience fighting in the New Mexico Territory during the 1850s.[17] Early in the American Civil War, he trained the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment as its colonel. His men considered him an excellent drillmaster, and at least one historian believed the regiment was "one of the best–trained and best–disciplined" volunteer cavalry regiments.[18][19] On September 26, 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general in the Army of the Potomac. On March 17, 1863, he performed well at the Battle of Kelly's Ford, a first for Union cavalry against Confederate cavalry in the east.[20] A few months later, Major General Joseph Hooker was unhappy with Averell's performance in Major General George Stoneman's 1863 railroad raid at Gordonsville, Virginia, and Averell was relieved of command of the 2nd Division of the Cavalry Corps, effective May 2.[20]

On May 10, 1863, Averell was assigned command of the Fourth Separate Brigade, VIII Corps in West Virginia. Historians debate on if Averell was sent to West Virginia as a punishment, or because he could train Union Army units in cavalry tactics.[20] The Union Army in West Virginia needed more mobility in order to be effective against Confederate cavalry and bushwhackers.[20] The mobility problem became apparent in spring 1863 with the Confederate cavalry success in western Virginia during the Jones–Imboden Raid.[21] Averell took command on May 23, and converted the 2nd, 3rd, and 8th West Virginia infantry regiments to mounted infantry. All three regiments were sent to a camp for instruction as Averell attempted to procure necessary equipment.[22] He needed horseshoes, horseshoe nails, clothing, and ammunition.[23] The only full cavalry regiment in his command, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was formed less than one year earlier with a colonel that was only 20 years old at the time.[24][Note 3]

Kelley's orders

Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelley was commander of the Union Army's Department of West Virginia. Kelley's orders for Averell, dated August 12, 1863, sent the brigade into West Virginia. At the time, Averell was near Moorefield, West Virginia with part of his command. His orders were to go to Huntersville, West Virginia, and drive the Confederate force commanded by Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson out of Pocahontas County. Another target on his mission was a saltpeter and gunpowder works in Pendleton County, West Virginia, which Averell could attack on his way to Huntersville. Finally, he was to go Lewisburg, West Virginia, and eliminate any enemy force stationed there. While there, he should seize the law books from the law library of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals located in the town, and bring the books to the Union fortification in Beverly, West Virginia.[28] Kelley stated that the "law library at Lewisburg was purchased for the western part of the State, and of course rightfully belongs to the new State of West Virginia. Our judges need it very much."[29][Note 4]

Two regiments from Averell's command that were detached, the 2nd and 10th West Virginia infantries, were instructed to meet Averell at Huntersville. The 2nd West Virginia Infantry was mounted.[32] Averell was told that, if possible, Brigadier General Eliakim P. Scammon would send a force from the Charleston area to assist at Lewisburg. No more than 10 days of rations could travel with Averell's Brigade, so it would be necessary to forage off the land.[29][32] Averell was also notified that although some supplies were being sent, no horses were available for Ewing's Battery. This meant that he would have to seize horses from landowners and issue receipts.[33]

Opposing forces

With the exception of the Union cavalry, the Battle of White Sulphur Springs was fought in West Virginia by West Virginia and Virginia units.[34] Some of the men from one of the Confederate units were from Greenbrier County, West Virginia, where the battle occurred.[35][36] Others were from adjacent counties such as Monroe and Mercer. Company G from 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Edgar's Battalion) came from White Sulphur Springs, and was known as the White Sulphur Rifles.[37]

Union army

As commander of the Department of West Virginia, Benjamin Kelly was headquartered in Cumberland, Maryland.[28] He did not participate in the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, but had responsibility for the territory and was Averell's direct superior officer. Averell's 4th Separate Brigade was split into several units stationed in multiple places. His force on August 26, en route to White Sulphur Springs, consisted of the 2nd, 3rd, and 8th West Virginia mounted infantry regiments. His command also included the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, Gibson's Cavalry Battalion (consisting of six companies), and the six guns of Ewing's Battery.[38] The 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry did not depart from Winchester as Averell did on August 5. Instead, it met Averell in Huntersville on August 23 after departing from Buckhannon on August 20.[39] It was slightly better supplied than the remaining portion of Averell's brigade, and had enough extra ammunition that it distributed some to the 3rd West Virginia.[40] Weapons used by the brigade were typically breech-loading carbines that used a cartridge.[41] At the battle, Averell commanded about 1,300 men.[42]

Confederate army

In August 1863, the Confederate Army controlled much of the Greenbrier Valley in West Virginia.[43] Confederate Major General Sam Jones commanded the Department of Western Virginia, and his headquarters were about 75 miles (121 km) south of Lewisburg at the Dublin Rail Depot for the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in Virginia.[Note 5] Although Jones did not participate directly in the battle, the men and territory were his responsibility.[45] Brigadier General John Echols commanded a brigade that was headquartered in Lewisburg, and Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson had a small cavalry brigade headquartered near Huntersville.[46][47] Jackson skirmished with Averell a week before the battle, and was involved in the pursuit of Averell after the battle—but did not participate in the battle at White Sulphur Springs. Most of the fighting at White Sulphur Springs was done by Echols' Brigade. At the time, Echols was in Richmond serving in a court of inquiry.[48] Colonel George S. Patton commanded the brigade in the absence of Echols.[42][Note 6] Key units for Patton at the beginning of the battle were the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment, the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion, the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment, and Chapman's Artillery.[50] At the battle, Patton commanded about 2,300 men.[42][Note 7] Further east, Brigadier General John D. Imboden, a native of Staunton, Virginia, commanded the Shenandoah Valley District.[52] Imboden's cavalry brigade did not fight at the battle, but was involved in the pursuit of Averell before and after the battle.[53]

Initial movements

During July 1863, most of Averell's 4th Separate Brigade was involved with small attacks on General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia as it retreated from the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. The 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry Regiment was detached during that month and into August, and was split with companies in West Virginia near Beverly, Cheat Mountain Summit, and Buckhannon.[54] After a few skirmishes in late July, Averell's brigade moved to Winchester, Virginia, on July 30.[55]

Hardy County

On August 5, 1863, Averell left Winchester and moved 28 miles (45 km) west across North Mountain to Wardensville in West Virginia's Hardy County.[23] They continued moving west by a similar distance on the next day, and arrived at Moorefield that evening. During those two days, Averell's scouts skirmished a few times with small groups of Confederates that belonged to Imboden's Cavalry Brigade. After a few days of rest, the brigade moved a short distance to Petersburg.[56][Note 8] Most of the citizens on the east side of Hardy County, such as those in Moorefield or Wardensville, were pro-Confederate, while the people on the west side of the county, including Petersburg, were more loyal to the Union.[57] Averell needed supplies, and decided to wait for them in Petersburg. While there, he received Kelley's orders dated August 12 concerning the gunpowder works, Huntersville, and Lewisburg.[28] He also received two sets of orders from Kelley dated August 14 that stated some supplies would arrive soon. This did not include horses for Ewing's Battery, forcing Averell to secure horses from property owners in the countryside.[58] During this time, Averell's force was often harassed by local bushwhackers, who used hit-and-run tactics to weaken the Union force while avoiding the risk of direct confrontation. Bushwhackers killed two and wounded four men from the cavalry, forcing Averell's men to always be alert. A local pro-Union home guard organization that consisted of about 50 men, known as the Swamp Dragons, provided assistance in driving off the Confederate guerrillas.[39]

Pendleton County

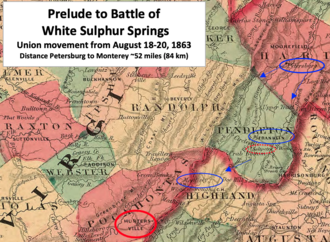

Averell received some supplies on August 17, but they included no small arms ammunition. However, he believed that further delay would dangerous and began his mission. The next day, he sent the 8th West Virginia, commanded by Colonel John H. Oley, south toward Franklin via the North Fork of the South Branch of the Potomac River. Gibson's Cavalry Battalion was sent to Franklin using a different route—the South Fork of the South Branch of the Potomac River.[23] On the morning of August 19, Averell moved close to Franklin with the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, and Ewing's Battery. From there, two squadrons destroyed the saltpeter works that were about five miles (8.0 km) further south. On the next day Averell moved southwest up the South Branch toward Monterey. He was joined by the 8th West Virginia and Gibson's Battalion.[23]

Highland County

Because of the irregular shape of the Virginia-West Virginia border, the trip from Franklin in West Virginia's Pendleton County to Huntersville was through Virginia's Highland County. The command was constantly harassed by bushwhackers, and the 14th Pennsylvania skirmished with them from sunrise to sunset. Averell stopped at Monterey for the evening of August 20, and rescued one of his scouts that had been caught wearing a Confederate uniform.[59] Averell also discovered that Confederate generals Imboden and Sam Jones had been in town on the previous day discussing a plan to attack Averell at Petersburg. The Union brigade departed early on August 21, moving southwest in the direction of Huntersville.[23]

By now, Confederate leaders had been monitoring Averell for at least ten days. Originally, Confederate leadership believed Averell was planning an attack on Staunton, Virginia, which was also a stop for the Virginia Central Railroad. Robert E. Lee's opinion differed, and he correctly believed Averell's targets were Huntersville and Lewisburg.[60] On August 21, Jones adjusted his troop locations in anticipation of Averell going eastward from Monterey to Staunton. He also asked Lee to send troops to Staunton.[61]

Huntersville

Averell moved on the road from Monterey toward Huntersville in Pocahontas County, West Virginia. He approached from the northeast, and his vanguard got within five miles (8.0 km) of Huntersville before stopping for the evening near Gibson's Store.[23] For this segment of the excursion, bushwhackers again used hit-and-run tactics against the Union brigade. Averell's wagon train was attacked by Confederate soldiers, and his vanguard drove back about 300 of Mudwall Jackson's men in front of the command.[55] Averell's after action report listed casualties for the day of four men wounded and six horses killed or disabled.[62] Another source adds that three wagons were destroyed and one of Averell's men was mortally wounded.[63]

During the night of August 21, Averell learned that Confederate soldiers were waiting in a ravine about three miles (4.8 km) from Huntersville. The next day, Averell sent Gibson's Battalion on what he called a "false advance", while the main portion of his force took a different road and reached Huntersville without any resistance.[62] Understanding that he had been outflanked and making sure he was not cut off from Warm Springs, Jackson moved east on the Warm Springs Road.[64] Averell sent Oley after Jackson, with the 8th West Virginia and a squadron of the 3rd West Virginia. Oley captured Jackson's Camp Northwest, burning buildings, wagons, supplies, and weapons. Some items, such as canteens, stretchers, and hospital supplies, were kept and added to the Union supplies. August 23 was spent waiting at Huntersville for the arrival the 2nd and 10th West Virginia infantry regiments, who arrived that day with a section from Keeper's Battery. The 2nd West Virginia had only nine companies, and Averell reported that it totaled to about 350 men. During the day, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Polsley led the 8th West Virginia on a reconnaissance mission toward Warm Springs and skirmished with Confederate soldiers.[62]

Warm Springs and Callaghan's

On August 24, Averell's brigade moved toward Warm Springs, Virginia, in Bath County. They arrived in Warm Springs not long after dark, and traveled a distance of 25 miles (40 km) from Huntersville.[39] Averell's strategy was to make Confederate leadership believe his targets were Confederate depots near Staunton, which was a stop for the Virginia Central Railroad. Jackson was chased back to Millboro, which is over the mountains east of Warm Springs in Bath County.[62] During this movement Averell's front was attacked by bushwhackers, but he captured over 100 bridles and saddles, which were burned.[39] At this time, Averell determined that he could not catch Jackson, and sent the 10th West Virginia back to Huntersville.[62] Still unclear on Jackson's fate, Confederate leadership now feared a raid on the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, and took steps to protect it.[45][65]

On August 25, Averell hurried his force 25 miles (40 km) to Callaghan's in Alleghany County, Virginia. On the way, they destroyed a saltpeter works on the Jackson River. After arriving at Callaghan's, reconnoitering parties were sent toward Covington, Virginia and Sweet Springs, West Virginia. Confederate wagons were captured near Covington, and a nearby saltpeter works was destroyed.[62] On the same day, Jones sent Patton's Brigade north, hoping to catch Averell between Patton and Jackson. Later in the day, Jones thought Averell was heading toward Staunton, and adjusted Patton's route.[66] At 10:00 pm Jones learned that Averell was moving from Warm Springs to Callaghan, so he again changed Patton's destination. Patton received Jones' message at 2:00 am August 26, and began hurrying back to Lewisburg.[67] Jones began a race against Averell to an intersection near White Sulphur Springs that was east of Lewisburg.[68] Patton would be approaching the intersection from the northeast, while Averell would be approaching from the southeast. If Averell got past the intersection first, there would be no significant force of Confederate Army regulars between Averell and the railroad.[68]

Battle

Edgar starts the battle

Patton's brigade marched for nearly 24 consecutive hours trying to find Averell. His advance, consisting of the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion, reached the junction of Anthony's Creek Road with the James River and Kanawha Turnpike on the morning of August 26 slightly ahead of Averell.[Note 9] The 26th Virginia was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George M. Edgar, and is often called Edgar's Battalion. Edgar's men quickly made a crude barricade on the road to Callaghan's by tearing down nearby fences.[69] The battalion had eight companies, which were split evenly on each side of the road at the intersection. Company B, commanded by Captain Edmund S. Read, was subsequently moved forward on the left.[70] Read's men occupied a house along the road owned by Henry Miller, and they began the battle by firing upon Averell's advance around 9:30 pm.[71][72]

Edgar's immediate task was to block the road until more of Patton's men arrived.[69] Edgar believed his battalion was facing a large Union force of at least 4,000 men, which was much larger than Averell's actual size of about 1,300 men.[73] He felt less apprehensive when Chapman's Battery, located on a hill behind Edgar, began firing at the Union soldiers. The artillery fire combined with Edgar's initial volleys to drive back Averell's vanguard.[74] It also held back Averell's brigade long enough for Patton to form his men in a line of battle.[75]

Averell's brigade had moved west from Callaghan's about 12 miles (19 km) when Averell received a message from his vanguard requesting reinforcements. The vanguard, led by Captain Paul von Köenig of Averell's staff, consisted of two companies each from the 2nd and 8th West Virginia mounted infantries.[62] Averell sent more men forward and began moving up the rest of his command through a narrow gorge. His column was four miles (6.4 km) long. Part of Ewing's Battery was brought forward and immediately engaged.[76]

Line of battle formed

Patton deployed the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment on his right, and the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment on his left. The 45th Virginia, commanded by Colonel William H. Browne, used 100 men led by Captain William H. Thompson to extend the battle line west and occupy a small hill.[77] Averell deployed the main body of the 8th West Virginia, commanded by Colonel Oley, on his left (Patton's right). The 2nd West Virginia took the right side of the road.[76] As the day progressed, Averell had Gibson's Cavalry Battalion, the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, the 2nd West Virginia, and three companies of the 3rd West Virginia on the right side of the road. On his left, he had the remaining portion of the 3rd West Virginia and the 8th West Virginia.[78]

Along the road, Ewing had two guns that were not strongly protected until the 3rd West Virginia and 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry arrived. Ewing used canister to defend against Edgar's Battalion. While he was reconnoitering for better positions for his guns, Ewing was severely wounded. Lieutenant Howard Morton, who brought up the other four guns, eventually assumed command when Ewing lost consciousness.[79] An artillery duel between Morton and the Confederates lasted for over 2 hours.[80] The leader of the Confederate artillery, Captain George Beirne Chapman, had a four–piece battery consisting of two 3-inch rifled guns, one 12-pounder howitzer, and one 24-pounder howitzer. One of the rifled guns was hit twice by Union artillery, and three of the four pieces were eventually withdrawn for repairs.[81] For the day and a small portion of the next day, Ewing's Battery lost one gun, used up all of its ammunition, and had 16 casualties.[9][61] Ewing's wound was serious enough that he could not be moved, and he was among those left with the enemy.[82]

Incessant fire

Averell brought the 2nd West Virginia and 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry to the right side of the road. Patten added the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Clarence Derrick, around 10:00 am.[83] With Derrick were 200 men from the 37th Virginia Infantry Battalion. Gibson's Cavalry Battalion was also sent to the right. A soldier from the 3rd West Virginia wrote that for the next four or five hours, an "almost incessant fire" of artillery and muskets took place as neither side gained the advantage.[84]

Averell tried attacking on all sides. On the right side of the road, the 2nd West Virginia unsuccessfully attacked the 22nd Virginia and two companies of the 23rd Virginia. Many of the attackers were wounded within 15 steps of the Confederate line.[85] The leader of the attacking force was Major Francis P. McNally, and he was mortally wounded and captured. At that time, the 2nd West Virginia was caught in an exposed position, so Averell had a portion of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry make a mounted charge on the road.[Note 10] Although they reached the Confederate barricades, they were surprised by an enfilading fire from enemy troops hidden in a cornfield.[82] The fighting at the barricades was hand-to-hand, with Confederates using musket and bayonet while the Union cavalry used sabers.[88] Captain John Bird, the leader of the charging 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry squadron, was wounded, captured, and eventually taken to Libby Prison.[89] Over 100 men from the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry were killed, wounded, or captured in the battle—nearly half of all Union casualties.[61] Colonel Schoonmaker's horse was killed, but he escaped on the horse of a nearby dead officer.[90] During the cavalry struggle, the 2nd West Virginia was able to retreat to a safer position on a ridge in their rear. Morton's artillery eventually swept the cornfield with canister.[91]

On Averell's left, the 3rd West Virginia was led by Lieutenant Colonel Francis W. Thompson, who led seven charges by the regiment.[78] Further to the left, Oley's dismounted 8th West Virginia applied pressure to Captain Thompson's force of 100 men from the 45th Virginia that occupied a small hill. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin H. Harman reinforced Thompson with an additional company and took command. The Confederate force repulsed Oley's attackers and placed a company forward about 110 yards beyond the Confederate left wing and perpendicular to the line. Colonel Browne and the remainder of the regiment joined Harman's force on the small hill, and continued repulsing Union attacks.[92] Browne later reported that he "repulsed eight separate and distinct charges" (including one on August 27) in addition to "frequent engagements" with skirmishers.[93] During many of the charges, Union soldiers came as close as 20 steps from the Confederate line.[93] Oley had two company commanders killed while charging the Confederate position.[94] Another officer, Captain William Parker, was mortally wounded.[61] Captain von Köenig, who was "Averell's most daring scout", was killed around 5:00 pm while on horseback searching for Oley.[95][Note 11]

After the fighting from the cavalry charges died down, Averell received reports that ammunition was in short supply. Based on the slackening of Confederate fire, he believed that the Confederates were also low on ammunition. The fighting stopped at nightfall, and all remaining ammunition was distributed. Averell concluded that he could not get to Lewisburg unless he was aided by troops from General Scammon. He decided to wait until morning to retreat in case Scammon's troops arrived or Patton retreated.[86] Every man was brought up to the front, and they slept on their weapons in line of battle. The Confederates unsuccessfully attempted to surprise the sleeping soldiers at least once.[98] Colonel James M. Corns and the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment arrived at the site of the battle around 2:00 am on August 27. Patton had three of Corns' companies moved to the front line while the remainder of the regiment was held in reserve.[99]

Morning retreat

The battle resumed around daybreak on the morning of August 27, and the Union force could not break the Confederate line.[100] At dawn the 45th Virginia repulsed another attack by Averell's men.[93] Around 9:00 pm the fiercest fighting shifted from the Union right to the left, and troops were shifted accordingly.[98] A Confederate bayonet charge drove the Union forces back from the main field of battle.[101] During the fighting, Averell prepared to withdraw by loading wagons and ambulances. Trees were partially chopped so they could easily fall across the road after the troops and wagons passed.[86] At 10:30 am, Averell gave the order to retreat, and force was moving toward Callaghan's 45 minutes later.[102]

As Averell's troops were withdrawn, trees were knocked across the road forming a barrier between the two armies. Morton's Battery G waited with double-shotted canister—the last of their ammunition. When Patton's men came forward the road with their Rebel yell, the battery fired at them and then left on fresh horses moving at a trot. More trees were added to the road, and then Averell's rear guard fired a volley at the Confederates from behind the trees.[100] The rear guard included, at various times, the 8th West Virginia, a company of the 2nd West Virginia, and cavalry.[Note 12]

Retreat and pursuit

Patton ordered Colonel Corns and the 8th Virginia Cavalry to pursue Averell's retreating brigade. He used a rifled artillery piece to dislodge the first of Averell's blockades. Further down the road, Corns discovered that the blockade was too difficult to remove quickly, and cavalry could not go around it. Averell's brigade reached Callaghan's about 5:00 pm on August 27, and had a short rest and meal. After dark, fires were left burning to deceive the enemy while the Union brigade departed on the road to Warm Springs.[102] They bypassed Warm Springs, leaving the main road and taking an obscure road to the Jackson River Valley, and then moved to the main road between Warm Springs and Huntersville.[105] From there they moved west to the point where the road intersects with the Back River—a place called Gatewood's where they arrived at sunrise on August 28.[102] His pursuer from the battle site, Corns, restarted the chase at 5:00 am on August 28.[106]

Averell had departed from Gatewood's at 9:00 am August 28, heading toward Huntersville.[102] Although he was far from Corns, he had not yet escaped from other pursuing forces. Colonel William Arnett and the 20th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, from Jackson's command, fired on Averell's rear guard and pursued them on the road to Huntersville.[107] Despite considerable harassment by guerrillas, Averell's brigade arrived at Marling's Bottom (six miles (9.7 km) northwest of Huntersville) in the evening, where Colonel Thomas Harris and the 10th West Virginia Infantry were posted with Keeper's Battery.[102] Corns arrived at Gatewood's before 10:00 pm that evening.[107] He believed that he could have caught Averell if Jackson would have blocked the road leading from the Warm Springs turnpike to Gatewood's.[106] On the next day, Corns arrived north of Huntersville at Marling's Bottom, and discovered he missed Averell's rear guard by two hours. At that time, with horses exhausted, he called off the pursuit. From his point of view, Jackson had done little to help.[106]

Averell's brigade moved north to Big Spring in Pocahontas County, and continued north at 2:00 am on August 30.[102] They cut through a blockade on August 30, and arrived at Beverly on August 31.[108] Averell's report devoted about half of a page to a retreat that lasted between three and four days, suggesting his retreat was orderly and deliberate.[102] However, abandoning wounded, night marches, road blockades, and fires left burning to deceive the enemy, are signs of concern about the safety of the brigade.[109] A soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Infantry described the retreat as "a hard, trying march, and we were mercilessly bushwhacked".[108]

Aftermath

Casualties from the battle

The road from Callagan's, from the Miller House to where it intersects with Anthony Creek Road, was "strewn with dead and wounded soldiers".[110] The two houses on the side of the road by the intersection, one known as the Dixon house and other a log house, were used as hospitals for both sides. Amputations were made at the log house, and arms and legs were piled as high as the window sills.[111]

Averell listed 26 officers and enlisted men killed, 125 wounded, and 67 captured or missing for a total of 218 casualties. The 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry had 102 of the casualties. Averell also reported that 2 officers (McNally and Parker) and 55 wounded men were left with the Confederates because of the severity of their wounds.[61] Patton reported that 117 Union soldiers were captured, including a major and three captains.[112]

Patton listed 20 officers and enlisted men killed, 129 wounded, and 13 missing for a total of 162 casualties. This total excludes any casualties for the 8th Virginia Cavalry, who did not report and did not fight on the first day. The 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment had the most casualties, with a total of 79.[99] Averell reported capturing 266 prisoners during the whole excursion.[102]

Performance and impact

Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Edgar wrote, "Of all the battles of the Civil War, fought in the Department of Western Virginia, none were more prolonged, more stubbornly fought, more creditable of the commanding officer and his subordinate officers of all arms, or to the rank and file, or more interesting in their details than that of White Sulphur Springs, Dry Creek, or Rocky Gap, as it has been variously called."[113][Note 13] A Confederate historian wrote that the "Battle of Dry Creek was one of the hottest, for the numbers engaged, of the war" and "its effect was to turn back Averell's army and preserve for many months a large scope of valuable territory from the devastations of Yankee invasion".[116]

With his Confederate victory, George Patton proved he could handle an independent command of an entire brigade, effectively meeting all attacks and efficiently using his artillery.[117] His defeat of Averell also meant that Sam Jones could shift his troops to Eastern Tennessee to help counter a threat of a Union army commanded by Major General Ambrose Burnside, who was approaching from the west.[118] John Imboden and William Jackson were not at the battle, and they were unable to catch Averell before or afterwards. In a letter to Imboden, Robert E. Lee implied that an opportunity had been missed, and that he hoped Imboden would be more successful in the future.[53]

William W. Averell was unable to get by Patton's Confederate forces, and the lawbooks were never captured. Shortly after the battle, the Lewisburg law library was sent to Richmond.[119] Averell achieved an objective of destroying the saltpeter works in Pendleton County. He also destroyed the Confederate Camp Northwest, including buildings, wagons, supplies, and weapons. A second saltpeter works was destroyed in Virginia. The fact that his brigade escaped from deep in Confederate territory is a testament to his ability.[120] This excursion was the beginning of Averell's transformation of the Union Army in West Virginia. His brigade began mostly as a group of loyal infantries that knew little of discipline or regimental maneuvers, and had little mobility. He trained them in cavalry tactics and three infantry regiments eventually became cavalry regiments. A major from the 6th West Virginia Cavalry Regiment (originally 3rd West Virginia Infantry) wrote that Averell's brigade became "noted as a terror to the enemy".[121]

Battlefield

As of 2011, little remains of the battlefield. The valley portion of the battlefield is a strip mall, and Interstate 64 runs through another portion. Three small monuments are located near a fast food restaurant at the intersection of West Virginia Route 92 and US Route 60. One, with a heading of "Dry Creek Battle" commemorates the battle.[122] Next to it is a small monument to Baron Paul von Köenig, who led some of the Union charges and was killed in the battle. The von Köenig monument was dedicated on November 9, 1914, by Colonel James M. Schoonmaker, who commanded the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry in the battle.[123] During the 1990s, the Civil War re-enactors known as the White Sulphur Rifles placed a third monument next to the original two.[122] On the other side of an adjacent creek, near a gas station across from a bank, is a historical marker erected by the West Virginia Historic Commission in 1963 titled "Dry Creek Battle".[124]

See also

- List of West Virginia Civil War Confederate units

- List of West Virginia Civil War Union units

- West Virginia in the Civil War

- Battle of Droop Mountain

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ The major issues that caused the American Civil War were slavery and the rights of states. In the north, abolitionists believed slavery was immoral and should not exist. The southern slaveholder states believed that the northern abolitionists were interfering with states' rights.[1]

- ^ A soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment called Lewisburg a "hot rebel town", and described its inhabitants cheering Confederate soldiers in a May 1862 battle.[11]

- ^ James M. Schoonmaker was 20 years old when he was made the original commander of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and the youngest regiment commander in the Union Army. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton objected to his commission because of his age, but Pennsylvania governor Andrew G. Curtain issued the commission.[25] On January 1, 1864, Schoonmaker became a brigade commander.[26] He received the Medal of Honor for actions in the Third Battle of Winchester.[27]

- ^ Virginia state law in Chapter 19, Section 19, of the Code of Virginia 1849, said that Virginia will have two libraries. One library in Lewisburg, and the other at the state capitol.[30] The purpose of the law library in Lewisburg was to serve the increasing number of citizens of Virginia located west of the mountains.[31]

- ^ Later in 1863, Jones called his command the Department of Western Virginia and East Tennessee.[44]

- ^ Colonel George S. Patton is the grandfather of the future World War II tank commander also named George S. Patton.[49]

- ^ Snell uses a count of the Confederate force of about 1,900.[51]

- ^ At the time, Petersburg was part of Hardy County. In 1866, a western portion of Hardy County was split into a new county named Grant, and Petersburg became the county seat of Grant County.[57]

- ^ Locally, the road to Huntersville was called Anthony's Creek Road. The James River and Kanawha Turnpike connected Callaghan's with White Sulphur Springs and Lewisburg.[68]

- ^ Averell described this as a 4:00 pm charge of a squadron of the 14th Pennsylvania, led by Captain Bird, that was "another effort to carry the position" and caused "about 300 of the enemy to run away".[86] Wittenberg describes a cavalry charge of 100 men led by Bird followed by a second charge consisting of the remainder of the cavalry.[87] A soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Infantry wrote that the charging force was "nearly all killed, wounded or captured".[82]

- ^ Sources conflict on the death of von Koenig. Wittenberg describes von Köenig being shot in the back by a Confederate sharpshooter while leading an attack with a detachment of the 14th Pennsylvania.[96] A source published in 1897 says von Köenig was killed by his own men in revenge for earlier mistreatment.[97] A newspaper article said von Köenig was shot by the enemy near the 3rd West Virginia while under the influence of alcohol.[78]

- ^ Wittenberg wrote that "Averell ordered the 8th West Virginia to cover the retreat".[103] The historian for the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry wrote that the cavalry "brought up the rear and skirmished with the advancing enemy day and night for thirty-five miles" (56.3 km).[104] A soldier from the 2nd West Virginia Mounted Infantry wrote that "Company C formed part of the rear guard", and discussed a small ambush on the morning of August 28 that put the company two miles (3.2 km) behind the main force.[100]

- ^ One historian wrote that Union veterans tended to call the battle "the Battle of Rocky Gap", while Confederate veterans usually referred to it as "the Battle of Dry Creek". He also wrote that other names used are "the Battle of Howard's Creek" and "the Battle of the Law Books".[114] A former governor of West Virginia wrote in 1916 that although the battle was "commonly known as the Battle of Dry Creek, this engagement should be named rather the Battle of the White Sulphur."[115] Modern discussions of the battle tend to call it the Battle of White Sulphur Springs.[114]

Citations

- ^ Stampp 1991, p. 19

- ^ "Civil War Facts". Civil War Trust. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ^ a b Snell 2011, Ch. 1 of e-book

- ^ "West Virginia History - Statehood for West Virginia: An Illegal Act?". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ Starr 1981, pp. 154–156

- ^ "Northwestern Virginia In 1861: The First Campaign". Rich Mountain Battlefield Foundation. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- ^ "Timeline of West Virginia: Civil War and Statehood September 6-16, 1862". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- ^ "Civil Neighbors to Violent Foes: Guerrilla Warfare in Western Virginia during the Civil War". Marshall University. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ a b MacCorkle 1916, p. 271

- ^ Snell 2011, Ch. 2 of e-book

- ^ Sutton 2001, p. 53

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 155

- ^ Whisonant 2015, pp. 156–157

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- ^ "Geology and the Civil War in Southwest Virginia: The Wythe County Mines" (PDF). Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Mineral Resources (May 1996). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Virginia Center for Civil War Studies - Wytheville". Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 8

- ^ Rawle 1905, p. 27

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 20

- ^ a b c d Lowry 1996, p. 10

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 25

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f Scott 1890, p. 33

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 21

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 32

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 18

- ^ "James Martinus Schoonmaker". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ^ a b c Scott 1890, pp. 38–39

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 40

- ^ "West Virginia Judiciary - WV State Law Library - Law Library History". West Virginia Court System - Supreme Court of Appeals. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ^ Kester, C. Doyle (West Virginia Antiquities Commission) (1970). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Greenbrier County Library and Museum" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (Maryland Historical Trust). Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ a b Wittenberg 2011, p. 39

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 40

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 106

- ^ Cole & Cole 1917, p. 165

- ^ Cole & Cole 1917, p. 91

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 60

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 34–35

- ^ a b c d Reader 1890, p. 203

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 48

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 34

- ^ a b c Wittenberg 2011, Appendix A

- ^ "The Civil War in West Virginia". West Virginia Archives and History. West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 525

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 42

- ^ "Rantings of a Civil War Historian - Brig. Gen. William L. "Mudwall" Jackson". Rantings of a Civil War Historian - Bringing Obscurity into Focus. Eric J. Wittenberg. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 47–48

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 57

- ^ "Patton Family at VMI". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 74

- ^ Snell 2011, Ch. 6 of e-book

- ^ Lowry 1996, p. 75

- ^ a b Wittenberg 2011, p. 132

- ^ Reader 1890, p. 201

- ^ a b Reader 1890, p. 202

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 37

- ^ a b "CCAWV - Grant County". County Commissioners' Association of West Virginia. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ Scott 1890, pp. 39–40

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 43

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e Scott 1890, p. 41

- ^ a b c d e f g Scott 1890, p. 34

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 44

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 47

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 65

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 66

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 67

- ^ a b c MacCorkle 1916, p. 264

- ^ a b MacCorkle 1916, p. 266

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 60

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 74–75

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 61

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 73–74

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 75

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 77

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 35

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 77–78

- ^ a b c "Gen. Averell's Brigade—March and Battle at White Sulpher Springs [sic]". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1863-09-09. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 81–82

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 53

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 65

- ^ a b c Reader 1890, p. 205

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 59

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 79

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 54

- ^ a b c Scott 1890, p. 36

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 93–94

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 269

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 54

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 91

- ^ Reader 1890, pp. 205–206

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 62

- ^ a b c Scott 1890, p. 63

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 80

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 229

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 96

- ^ Maxwell & Swisher 1897, p. 216

- ^ a b Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 92

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 56

- ^ a b c Reader 1890, p. 206

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 270

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scott 1890, p. 37

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 110

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 93

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 117

- ^ a b c Scott 1890, p. 57

- ^ a b Scott 1890, p. 51

- ^ a b Reader 1890, p. 207

- ^ Starr 1981, p. 160

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 268

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, pp. 270–271

- ^ Scott 1890, p. 55

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 128

- ^ a b Wittenberg 2011, p. 10

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 272

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 129

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 131

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, pp. 131–132

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 134

- ^ Wittenberg 2011, p. 139

- ^ Lang 1895, p. 109

- ^ a b Wittenberg 2011, p. 137

- ^ Slease & Gancas 1999, p. 231

- ^ "West Virginia Memory Project - West Virginia Highway Markers Database (scroll down to Dry Creek Battle)". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

References

- Cole, John Rufus; Cole, Joseph R. (1917). History of Greenbrier County. Lewisburg, West Virginia: J.R. Cole. OCLC 33146733.

- Lang, Joseph J. (1895). Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865 : With an Introductory Chapter on the Status of Virginia for Thirty Years Prior to the War. Baltimore, MD: Deutsch Publishing Co. OCLC 779093.

- Lowry, Terry (1996). Last Sleep: The Battle of Droop Mountain, November 6, 1863. Charleston, West Virginia: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-024-1. OCLC 36488613.

- MacCorkle, William Alexander (1916). The White Sulphur springs; the Traditions, History, and Social Life of the Greenbriar White Sulphur Springs. Charleston, West Virginia: W.A. MacCorkle. OCLC 11083303. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- Maxwell, Hu; Swisher, Howard Lleyellyn (1897). History of Hampshire County, West Virginia: from its Earliest Settlement to the Present. Morgantown, West Virginia: A.B. Boughner. OCLC 1052674504. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- Rawle, William Brooke (1905). History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, Sixtieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, in the American Civil War, 1861-1865. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Franklin Printing Company. OCLC 1683643. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- Reader, Frank S. (1890). History of the Fifth West Virginia Cavalry, Formerly the Second Virginia Infantry, and of Battery G, First West Virginia Light Artillery. New Brighton, Pennsylvania: Daily News, Frank S. Reader, Editor and Proprietor. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1890). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXIX Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Slease, William Davis; Gancas, Ron (1999) [1915]. The Fourteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War: A History of the Fourteenth Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry from its Organization until the Close of the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Soldiers' & Sailors' Memorial Hall and Military Museum. ISBN 978-0-96449-529-6. OCLC 44503009.

- Snell, Mark A. (2011). West Virginia and the Civil War : Mountaineers are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-390-9. OCLC 829025932.

- Stampp, Kenneth (1991). The Causes of the Civil War: Revised Edition. New York: Touchtone. ISBN 978-0-6717-5155-5.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1981). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy: How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2011). The Battle of White Sulphur Springs: Averell Fails to Secure West Virginia. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-326-8. OCLC 795566215.