Battle of the Trebia

| Battle of the Trebia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

Matthäus Merian the Elder, "Battle of Trebbia" (1625) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rome | Carthage | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sempronius Longus | Hannibal | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Approximate location of the battle, shown on a map of modern north Italy | |||||||

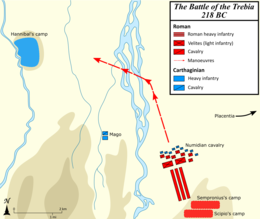

The Battle of the Trebia (or Trebbia) was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Sempronius Longus on 22 or 23 December 218 BC. Each army had a strength of about 40,000 men; the Carthaginians were stronger in cavalry, the Romans in infantry. The battle took place on the flood plain of the west bank of the lower Trebia River, not far from the settlement of Placentia (modern Piacenza), and resulted in a heavy defeat for the Romans.

War broke out between Carthage and Rome in 218 BC. The leading Carthaginian general, Hannibal, responded by leading a large army out of Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal), through Gaul, across the Alps and into Cisalpine Gaul (in northern Italy). The Romans went on the attack against the reduced force which had survived the rigours of the march, and Publius Scipio personally led the cavalry and light infantry of the army he commanded against the Carthaginian cavalry at the Battle of Ticinus. The Romans were soundly beaten and Scipio was wounded. The Romans retreated to near Placentia, fortified their camp and awaited reinforcement. The Roman army in Sicily under Sempronius was redeployed to the north and joined with Scipio's force. After a day of heavy skirmishing in which the Romans gained the upper hand, Sempronius was eager for a battle.

Hannibal used his Numidian cavalry to lure the Romans out of their camp and onto ground of his choosing. Fresh Carthaginian cavalry routed the outnumbered Roman cavalry and Carthaginian light infantry outflanked the Roman infantry. A previously hidden Carthaginian force attacked the Roman infantry in the rear. Most of the Roman units then collapsed and most Romans were killed or captured by the Carthaginians, but 10,000 under Sempronius maintained formation and fought their way out to the safety of Placentia. Recognising the Carthaginians as the dominant force in Cisalpine Gaul, Gallic recruits flocked to them, and Hannibal's army grew to 60,000. The following spring, it moved south into Roman Italy and gained another victory at the Battle of Lake Trasimene. In 216 BC Hannibal marched to southern Italy and inflicted the disastrous defeat of the Battle of Cannae on the Romans, the last of what modern historians describe as the three great military calamities suffered by the Romans in the first three years of the war.

Background

Pre-war

The First Punic War was fought from 264 to 241 BC between Carthage and Rome: these two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC struggled for supremacy primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters and in North Africa.[1] The war lasted for 23 years until the Carthaginians were defeated.[2][3] Five years later an army commanded by the leading Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca landed in Carthaginian Iberia (modern south-east Spain) which he greatly expanded and turned into a quasi-monarchical, autonomous territory ruled by his family, the Barcids.[4] This expansion gained Carthage silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards and territorial depth, which encouraged it to resist future Roman demands.[5]

Hamilcar ruled Carthaginian Iberia autonomously until his death in 228 BC. He was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal and in 221 BC by his son Hannibal.[6] In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty established the Ebro River as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence in Iberia.[7] A little later Rome made a separate treaty of association with the independent city of Saguntum (modern Sagunto), well south of the Ebro.[8] In 219 BC a Carthaginian army under Hannibal besieged, captured and sacked Saguntum,[9][10] which led Rome to declare war on Carthage.[11]

War in Cisalpine Gaul

It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year as senior magistrates, known as consuls, who in time of war would each lead an army.[12][13] In 218 BC the Romans raised an army to campaign in Iberia under the consul Publius Scipio, who was accompanied by his brother Gnaeus. The major Gallic tribes in the area of north Italy either side of the River Po known as Cisalpine Gaul were antagonised by the settling of Roman colonists at Piacentia (modern Piacenza) and Cremona earlier that year on traditionally Gallic territory. They rose and attacked the Romans, capturing several towns. They repeatedly ambushed a Roman relief force and blockaded it in Tannetum.[14] The Roman Senate detached one Roman and one allied legion from the force intended for Iberia to send to the region. The Scipios had to raise fresh troops to replace these and thus could not set out for Iberia until September.[15]

Carthage invades Italy

Meanwhile, Hannibal assembled a Carthaginian army in the Iberian city of New Carthage (modern Cartagena) in late 219 and early 218 BC. This marched north in May 218 BC, entering Gaul to the east of the Pyrenees, then taking an inland route to avoid Roman allies along the coast.[16][17] Hannibal left his brother Hasdrubal Barca in charge of Carthaginian interests in Iberia. The Roman fleet carrying the Scipio brothers' army landed at Rome's ally Massalia (modern Marseille) at the mouth of the River Rhone in September, at about the same time as Hannibal was fighting his way across the river against a force of local Allobroges at the Battle of Rhone Crossing.[18][19][17] A Roman cavalry patrol scattered a force of Carthaginian cavalry, but Hannibal's main army evaded the Romans and Gnaeus Scipio continued to Iberia with the Roman force;[20][21] Publius returned to Italy.[21] The Carthaginians crossed the Alps with 38,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry[16] in October, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain[16] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes.[22]

Hannibal arrived with 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and about 30 war elephants from the force with which he had left Iberia[23][24][25] in what is now Piedmont, northern Italy. The Romans had already withdrawn to their winter quarters and were astonished by Hannibal's appearance.[26] The Carthaginians needed to obtain supplies of food, as they had exhausted theirs during their journey. They also wanted to obtain allies among the north-Italian Gallic tribes from which they could recruit, to build up their army to a size which would enable it to effectively take on the Romans. The local tribe, the Taurini, were unwelcoming, so Hannibal promptly besieged their capital (near the site of modern Turin), stormed it, massacred the population and seized the supplies there.[27][28] With these brutal actions Hannibal was sending out a clear message to the other Gallic tribes as to the likely consequences of non-cooperation.[29]

Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, Hannibal assumed the Roman army in Massalia, which he had believed en route to Iberia, had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north.[note 1] Believing that he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral.[31][30] Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.[32]

First contact

After camping at Placentia the Romans constructed a pontoon bridge across the lower River Ticinus and continued west. With his scouts reporting the nearby presence of Carthaginians, Scipio ordered his army to encamp. The Carthaginians did the same.[33] Next day each commander led out a strong force to personally reconnoitre the size and make-up of the opposing army, things of which they would have been almost completely ignorant.[34][35] Scipio mixed a large force of velites (javelin-armed light infantry) with his main cavalry force, anticipating a large-scale skirmish.[34][36][37][38] Hannibal put his close-order cavalry in the centre of his line, with his light Numidian cavalry on the wings.[36][39]

On sighting the Roman infantry the Carthaginian centre immediately charged and the javelin-men fled back through the ranks of their cavalry.[40] A large mêlée ensued, with many cavalry dismounting to fight on foot[note 2] and many of the Roman javelin-men reinforcing the fighting line.[43][44] This continued indecisively until the Numidian cavalry swept round both ends of the line of battle and attacked the still disorganised velites, the small Roman cavalry reserve to which Scipio had attached himself, and the rear of the already engaged Roman cavalry, throwing them all into confusion and panic.[40][34] The Romans broke and fled, with heavy casualties.[45][36] Scipio was wounded and only saved from death or capture by his 16-year-old son, also named Publius Cornelius Scipio.[40] That night Scipio broke camp and retreated over the Ticinus; the Carthaginians captured 600 of his rearguard the next day.[43]

The Romans withdrew as far as Placentia. Two days after this clash the Carthaginians crossed the River Po and marched towards Placentia. They formed up outside the Roman camp and offered battle, which Scipio refused. The Carthaginians set up their own camp some 8 kilometres (5 mi) away.[46] That night 2,200 Gallic troops serving with the Roman army attacked the Romans closest to them in their tents and deserted to the Carthaginians, taking the Romans' heads with them as a sign of good faith.[46][47] Hannibal rewarded them and sent them back to their homes to enrol more recruits. Hannibal also made his first formal treaty with a Gallic tribe and supplies and recruits started to come in.[46] The Romans abandoned their camp and withdrew under cover of night. The next morning the Carthaginian cavalry bungled their pursuit and the Romans were able to set up camp on an area of high ground by the River Trebia at what is now Rivergaro, a little south west of Placentia. Even so, they had to abandon much of their baggage and heavier gear and many stragglers were killed or captured.[48][49] Scipio waited for reinforcements while Hannibal camped at a distance on the plain on the other side of the river, gathering supplies and training the Gauls now flocking to his standard.[50]

Prelude

Rome's other consul, Sempronius Longus, had been assembling an army in western Sicily, with which it was planned to invade Africa the following year.[26] Shocked by Hannibal's arrival and Scipio's setback, the Senate ordered this army to move north to assist Scipio. It probably covered part of the distance by sea as it arrived at Ariminum (modern Rimini) only 40 days later.[50] Sempronius's army then marched to join Scipio's on the Trebia and set up camp alongside it. As Scipio was still partly incapacitated by his wounds Sempronius took overall command. Meanwhile, Hannibal bribed a force of Roman allies from Brundisium (modern Brindisi) garrisoning a large grain depot at Clastidium (modern Casteggio), 40 kilometres (25 mi) to the west, into surrendering the place. This resolved any remaining Carthaginian logistical difficulties.[51]

During the Punic Wars formal battles were usually preceded by the two armies camping two to twelve kilometres (1–8 miles) apart for days or weeks; sometimes forming up in battle order each day. During these periods when armies were encamped in close proximity it was common for their light forces to skirmish with each other, attempting to gather information on each other's forces and achieve minor, morale-raising victories. These were typically fluid affairs and viewed as preliminaries to any subsequent battle.[34][37] In such circumstances either commander could prevent a battle from occurring; unless both commanders were to at least some degree willing to give battle, either side might march off without engaging.[52][53] Forming up in battle order was a complicated and premeditated affair, which took several hours. Infantry were usually positioned in the centre of the battle line, with light infantry skirmishers to their front and cavalry on each flank.[54] Many battles were decided when one side's infantry force was partially or wholly enveloped and attacked in the flank or rear.[55][56] In 218 BC the two armies established camps about 8 kilometres (5 mi) from each other on opposite sides of the River Trebia. The Romans' was on an easily defended low hill to the east of the Trebia and the Carthaginians' was on high ground to the west.[57]

While waiting to see what Sempronius would do, Hannibal came to believe some of the Gauls in the immediate area were communicating with the Romans. He sent a force of 3,000 men, partly composed of Gauls, to devastate the area and plunder their settlements. Sempronius sent a force of cavalry – large, but of unknown size – supported by 1,000 velites to challenge them. As they were dispersed between a large number of settlements and many were burdened with plunder and looted food, the Carthaginians were easily routed and fled back to their camp. The Romans pursued, but were in turn thrown back by the Carthaginian reserve force on duty at the camp. Roman reinforcements were called in, eventually amounting to all 4,000 of their cavalry and 6,000 light infantry. How many Carthaginians were involved is unclear, but a large, fast-moving conflict sprawled across the plain. Hannibal was concerned that it would develop into a full-scale battle in a manner which he would not be able to control, so he recalled his troops and took personal command of reforming them immediately outside his camp. This brought the fighting to an end, as the Romans were unwilling to attack uphill against an enemy who would be supported by missile fire from within their camp. The Romans withdrew, claiming the victory: they had inflicted more casualties and the Carthaginians had abandoned the field of battle to them.[58][59]

Hannibal had deliberately brought the battle to a close, but Sempronius interpreted events as the Roman cavalry having dominated the Carthaginians. Sempronius was eager for a full-scale battle: he wished it to take place before Scipio fully recovered and so would be able to share the glory of an anticipated victory. He was also aware that he would be superseded in his position in less than three months, when the new consuls would take up their positions. Hannibal was also ready for a set-piece battle: he wished his new Gallic allies to participate in a victory before boredom and winter weather provoked desertions; and was possibly concerned by the recent suspected Gallic treachery in the immediate area. He also preferred to fight a battle on the flat and open floodplain of the Trebia, where the manoeuvrability of his cavalry could be used to greatest effect, to the hillier ground away from the river where the Roman heavy infantry would have found it easier to dominate. From the enthusiastic way in which Sempronius had reinforced his cavalry, Hannibal felt confident that he could provoke a battle at a time and place of his choosing.[60][61]

Opposing forces

Roman

Most male Roman citizens were liable for military service and would serve as infantry, with a better-off minority providing a cavalry component. Traditionally, when at war the Romans would raise two legions, each of 4,200 infantry[note 3] and 300 cavalry. Approximately 1,200 of the infantry – poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary – served as javelin-armed skirmishers known as velites; they each carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, a short sword and a 90-centimetre (3 ft) circular shield.[64] The balance were equipped as heavy infantry, with body armour, a large shield and short thrusting swords. They were divided into three ranks, of which the front rank, known as hastati, also carried two javelins. The second rank, known as principes, were very similarly equipped but wore better armour and consisted of older, more experienced men. The third rank consisted of the triarii, the veterans of the army, equipped with a thrusting spear instead. Both legionary sub-units and individual legionaries fought in relatively open order.[65]

A consular army was usually formed by combining a Roman legion with a similarly sized and equipped legion provided by their Latin allies; allied legions usually had a larger attached complement of cavalry than Roman ones.[12][13] In 218 BC each consul was leading a larger army of four legions, two Roman and two provided by its allies, for a total of approximately 20,000 men.[66]

The combined force which Sempronius led into battle included four Roman legions. At full strength these should have mustered 16,800 men, including 4,800 velites; at least one of the legions is known to have been significantly understrength. The near-contemporary Greek historian Polybius gives a total of 16,000 Romans, the Roman historian Livy, writing 200 years later, gives 18,000. In addition there were approximately 20,000 allied infantry, comprising four Latin allied legions and a strong force of Gauls. Mention is made of 6,000 light infantry and it is unclear whether these are included in the 36,000, or 38,000, infantry or in addition to them. As the nominal total number of velites from eight legions is 9,600, and it is known that many were lost at the Battle of the Ticinus, most modern historians assume that the 6,000 are included within the total number of infantry given. There were also 4,000 cavalry, a mixture of Romans, Latin allies and Gauls.[67]

Carthaginian

Carthaginian citizens only served in their army if there was a direct threat to the city of Carthage.[68][69] In most circumstances Carthage recruited foreigners to make up its army.[note 4] Many were from North Africa and these were frequently referred to as "Libyans". The region provided several types of fighters, including: close-order infantry equipped with large shields, helmets, short swords and long thrusting spears; javelin-armed light infantry skirmishers; close-order shock cavalry[note 5] (also known as "heavy cavalry") carrying spears; and light cavalry skirmishers who threw javelins from a distance and avoided close combat; the latter were usually Numidians.[72][73] The close-order African infantry fought in a tightly packed formation known as a phalanx.[74] On occasion some of the infantry would wear captured Roman armour, especially among Hannibal's troops.[75]

In addition both Iberia and Gaul provided many experienced infantry and cavalry. The close-order or "heavy" infantry from these areas were unarmoured troops who would charge ferociously, but had a reputation for breaking off if a combat was protracted.[72][76] The Gallic cavalry, and possibly some of the Iberians, wore armour and fought as close-order troops; most or all of the mounted Iberians were light cavalry.[77] Slingers were frequently recruited from the Balearic Islands.[78][79] The Carthaginians also employed war elephants; North Africa had indigenous elephants at the time.[note 6][76][81] The sources are not clear as to whether they carried towers containing fighting men.[82]

Hannibal had arrived in Italy with 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry.[23][83] At Trebia this had grown to 29,000 infantry – 21,000 close-order and 8,000 light infantry – and 11,000 cavalry. In each case they would be a combination of Africans, Iberians and Gauls; the proportions are not known, other than that 8,000 of the close-order infantry were Gauls. In addition there were about 30 elephants, the survivors of the 37 with which he had left Iberia.[84][25]

Battle

Early stages

The terrain between the Carthaginian camp and the Trebia was an unwooded flood plain, where it was apparently impossible to stage an ambush.[39] Hannibal, however, had his younger brother Mago take 1,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry during the night to the south of where he intended to fight the battle and secrete themselves in an old watercourse full of brush.[85]

The next morning, either 22 or 23 December, was cold and snowy. Shortly before daybreak Hannibal sent his Numidian cavalry across the river to force back the Roman pickets and provoke a fight. Meanwhile, the rest of his army ate an early breakfast and prepared for battle. When the Numidians appeared Sempronius ordered out all of his cavalry to chase them off. Polybius writes "the Numidians easily scattered and retreated, but afterwards wheeled round and attacked with great daring—these being their peculiar tactics."[86] The confrontation broke down into a wheeling mass of cavalry, but with the Numidians refusing to withdraw, Sempronius promptly ordered out first his 6,000 velites and then his whole army; he was so eager to give battle that few, if any, of the Romans had eaten breakfast. The Numidians withdrew slowly and Sempronius pushed his whole army after them, in three columns, each 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) long, through the icy waters of the Trebia, which was running chest-high. The Romans were met by the Carthaginian light infantry; behind them the entire Carthaginian army was forming up for battle. The Romans also organised themselves in battle formation and advanced.[87][88]

The cavalry of both sides fell back to their positions on the wings. The large number of light infantry in each army – entirely javelin-men for the Romans, a mixture of javelin-men and slingers from the Balearics for the Carthaginians – skirmished between the main armies. The Roman velites had used many of their javelins against the Carthaginian cavalry, while the Carthaginian skirmishers were fully supplied, and the slingers among the Carthaginians outranged the velites by some distance. As opposed to their opponents, the velites were unfed, and also tired and cold from having forded the Trebia. For these reasons the Carthaginians got the better of the initial skirmishing and drove the velites back through the gaps in their supporting heavy infantry. The Carthaginian light infantry then moved towards the flanks of their army and harassed the Roman cavalry with their missiles, before finally falling back behind their own cavalry as the gap between the armies closed.[67][89]

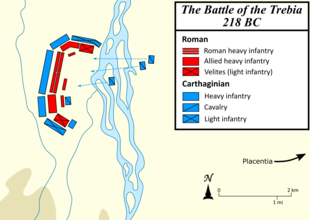

Formations

The Carthaginian army formed up symmetrically: the 8,000 Gallic infantry were in the centre; on each side of them was a formation of 6,000 African and Iberian veteran infantry; on the far side of each of these were half of the surviving elephants; and on each wing were 5,000 cavalry. The Romans too formed up symmetrically: the Roman heavy infantry were in the centre, perhaps 13,000 strong; on each side of them were part of their allied force, some 17,000 in total – this included a force of still-loyal Cisalpine Gauls, but the sources are unclear as to how many or where they were positioned. The survivors of the 6,000 velites were regrouping to their rear. Like the Carthaginians, the Romans divided their 4,000 cavalry between their wings.[57]

Engagement

The Romans had a total of approximately 30,000 heavy infantry to the Carthaginians' 20,000 and could expect sooner or later to overwhelm their opponents by weight of numbers. The Carthaginian line was also in danger of being outflanked by the stronger Roman force; to guard against this Hannibal thinned the Carthaginian line, especially that of the Gauls in the centre, to be able to lengthen it to match the Romans'. Also, with tactical forethought typical of him, he had positioned the elephants on either side of the infantry, which discouraged the Roman infantry from approaching their flanks too closely.[90]

On each wing 5,000 Carthaginian and 2,000 Roman cavalry charged each other. The Roman cavalry were not only outnumbered, but their horses were tired from chasing the Numidian cavalry and many had been wounded by the missiles of the Carthaginian light infantry.[57] Both encounters ended rapidly, with the Romans fleeing back over the Trebia and most of the Carthaginian cavalry pursuing them. Goldsworthy describes the fight put up by the Roman cavalry as "feeble",[91] while the military historian Philip Sabin says that the two contests were "speedily decided".[56] The Carthaginian light infantry, who had withdrawn to the wings behind the cavalry, moved forward and round the now exposed Roman flanks. The Roman light infantry, who had withdrawn to the rear of Roman heavy infantry, turned to face this developing Carthaginian threat.[91] Many of the Roman allied heavy infantry on each flank also turned to their flanks to face this new threat, which inevitably took much of the impetus out of their parent formation's push against the African and Iberian infantry to their fronts.[92]

At the same time, unnoticed in the heat of battle, Mago's force of 2,000 had been making its way down the watercourse, onto the plain and into a position where they could attack the Romans' left rear. While all this was happening, the fighting between the two heavy infantry contingents had continued fiercely, with the more numerous and better armoured Romans getting the better of it; despite being weakened by many of their component units having to turn to the flank or rear.[92] Mago's force charged into the velites who were already fending off the Carthaginian light infantry, but their formation held. Some of the rear rank of the legions, the triarii, turned to assist the velites. Increasing numbers of Carthaginian cavalry broke off their pursuit, returned and attacked the Roman rear. Eventually the strain told and the units of Latin allies and Gauls on the flanks and the velites to the rear started to break up.[90][93]

Meanwhile, the Roman infantry in the centre routed the 8,000 Gauls facing them, as well as a unit of African heavy infantry, and broke clean through the centre of the Carthaginian army. By the time they halted their pursuit and reorganised it was clear the rest of their army behind them had dissolved and that the battle was lost. Sempronius, who was fighting with the Roman infantry, ordered them away from the site of the battle and, maintaining their formation, 10,000 of them re-crossed the Trebia and reached the nearby Roman-held settlement of Placentia without interference from the Carthaginians. The Carthaginians concentrated on pursuing and cutting down the partially surrounded balance of the Roman army.[94]

Casualties

There is debate among modern historians as to the Roman losses. Dexter Hoyos states that the only Roman survivors were the infantry who broke through the Carthaginian centre.[95] Richard Miles says that "many" not in this group were killed;[96] Nigel Bagnall writes that only a minority of the Roman cavalry survived.[97] Goldsworthy states that the Romans "suffered heavily", but that "numbers of soldiers" straggled into Placentia or one of their camps in addition to the formed group of 10,000,[98] while John Lazenby argues that outside of the 12,500, "few" infantry escaped, although "most" of the cavalry did,[99] as does Leonard Cottrell.[100] According to Paul Erdkamp, the Romans lost 20,000 killed during the battle, half of their force; this excludes those captured.[101]

Carthaginian losses are generally agreed to have been several thousand of the Gallic infantry in the centre, a smaller number of their other infantry and of their cavalry; and several elephants.[99][97][95] Many of the African infantry were re-equipped with captured Roman armour and weapons.[102]

Aftermath

As was usual at the time, the Romans had left a strong guard at their camps. On hearing the news of the defeat the wounded Scipio gathered them together and marched to Placentia, where he joined Sempronius.[99] When news of the defeat reached Rome it initially caused panic. But this calmed once Sempronius arrived, to preside over the consular elections in the usual manner. Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius were selected and Sempronius then returned to Placentia to see out his term to 15 March.[103] The Carthaginian cavalry isolated both Placentia and Cremona, but these could be supplied by boat up the Po. The consuls-elect recruited further legions, both Roman and from Rome's Latin allies; reinforced Sardinia and Sicily against the possibility of Carthaginian raids or invasion; placed garrisons at Tarentum and other places for similar reasons; built a fleet of 60 quinqueremes (large galleys); and established supply depots at Ariminum and Arretium (modern Arezzo) in Etruria in preparation for marching north later in the year.[103] Two armies – of four legions each, two Roman and two allied, but with stronger than usual cavalry contingents[104] – were formed. One was stationed at Arretium and one on the Adriatic coast; they would be able to block Hannibal's possible advance into central Italy and be well positioned to move north to operate in Cisalpine Gaul.[105]

According to Polybius, the Carthaginians were now recognised as the dominant force in Cisalpine Gaul and most of the Gallic tribes sent plentiful supplies and recruits to Hannibal's camp. Livy, however, claims the Carthaginians suffered from a shortage of food throughout the winter.[106] In Polybius's account there were only minor operations during the winter and most of the surviving Romans were evacuated down the Po and assigned to one of the two new armies being formed,[104] while the flow of Gallic support for the Carthaginians became a flood and their army grew to 60,000.[107] Livy retails dramatic accounts of winter confrontations, but Goldsworthy describes these as "probably an invention".[104]

Subsequent campaigns

In spring 217 BC, probably early May,[108] the Carthaginians crossed the Apennine Mountains unopposed, taking a difficult but unguarded route.[109] Hannibal attempted without success to draw the main Roman army under Gaius Flaminius into a pitched battle by devastating the area.[110] The Carthaginians then flanked Flaminius, cutting his supply line to Rome, which provoked him into a hasty pursuit without proper reconnaissance.[111] That the Carthaginians continued to lay waste to farms and villages on their line of march probably spurred Flaminius and his men in their pursuit.[112] Hannibal set an ambush[111] and in the Battle of Lake Trasimene surprised and completely defeated the Romans, killing Flaminius[111] and another 15,000 Romans and taking 15,000 prisoner. A cavalry force of 4,000 from the other Roman army was also engaged and wiped out.[113]

Roman prisoners were treated badly, but captured Roman allies were treated well. Many were soon freed and sent back to their cities, in the hope that they would speak well of Carthaginian martial prowess and of their treatment.[96][114] Hannibal hoped some of these allies could be persuaded to defect and marched south in the hope of winning over some of the ethnic Greek and Italic city states.[105][115] There, the following year, Hannibal won a victory at Cannae which Richard Miles describes as "Rome's greatest military disaster".[116] The historian Toni Ñaco del Hoyo describes the Trebia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae as the three "great military calamities" suffered by the Romans in the first three years of the war.[117] Subsequently the Carthaginians campaigned in southern Italy for a further 13 years.[113]

In 204 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of the Scipio who had been wounded at Ticinus, invaded the Carthaginian homeland and defeated the Carthaginians in two major battles and won the allegiance of the Numidian kingdoms of North Africa. Hannibal and the remnants of his army were recalled from Italy to confront him.[118] They met at the Battle of Zama in October 202 BC[119] where Hannibal was decisively defeated.[119] As a consequence Carthage agreed a peace treaty which stripped it of most of its territory and power.[120]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- ^ The Roman army in Massalia had, in fact, continued to Iberia under Publius's brother, Gnaeus; only Publius had returned.[30]

- ^ The stirrup had not been invented at the time, and Archer Jones believes its absence meant cavalrymen had a "feeble seat" and were liable to come off their horses if a sword swing missed its target.[41] Sabin states that cavalry dismounted to gain a more solid base to fight from than a horse without stirrups.[38] Goldsworthy argues that the cavalry saddles of the time "provide[d] an admirably firm seat" and that dismounting was an appropriate response to an extended cavalry versus cavalry mêlée. He does not suggest why this habit ceased once stirrups were introduced.[42] Nigel Bagnall doubts that the cavalrymen dismounted at all, and suggests that the accounts of them doing so reflect the additional men carried by the Gallic cavalry dismounting and that the velites joining the fight gave the impression of a largely dismounted combat.[36]

- ^ This could be increased to 5,000 in some circumstances,[62] or, rarely, even more.[63]

- ^ Roman and Greek sources refer to these foreign fighters derogatively as "mercenaries", but the modern historian Adrian Goldsworthy describes this as "a gross oversimplification". They served under a variety of arrangements; for example, some were the regular troops of allied cities or kingdoms seconded to Carthage as part of formal treaties, some were from allied states fighting under their own leaders, many were volunteers from areas under Carthaginian control who were not Carthaginian citizens. (Which was largely reserved for inhabitants of the city of Carthage.)[70]

- ^ "Shock" troops are those trained and used to close rapidly with an opponent, with the intention of breaking them before, or immediately upon, contact.[71]

- ^ These elephants were typically about 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) high at the shoulder and were distinct from the larger African bush elephant.[80]

Citations

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 157.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 220.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 219–220, 225.

- ^ Miles 2011, pp. 222, 225.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, pp. 22–25.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Zimmermann 2015, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Mahaney 2008, p. 221.

- ^ a b Briscoe 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Fronda 2015, p. 252.

- ^ Zimmermann 2015, p. 291.

- ^ a b Edwell 2015, p. 321.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Erdkamp 2015, p. 71.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, pp. 100, 107.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2001, p. 33.

- ^ a b Zimmermann 2015, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Hoyos 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 266.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 52.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 169.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c d Goldsworthy 2006, p. 170.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d Bagnall 1999, p. 172.

- ^ a b Koon 2015, p. 83.

- ^ a b Sabin 1996, p. 69.

- ^ a b Fronda 2015, p. 243.

- ^ a b c Lazenby 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Jones 1987, pp. 9, 103.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Koon 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Bagnall 1999, p. 173.

- ^ Rawlings 1996, p. 88.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 114.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 173.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 174.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 64.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Koon 2015, p. 80.

- ^ a b Sabin 1996, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy 2006, p. 175.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 55.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 175.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 287.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 50, 227.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Scullard 2006, p. 494.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Jones 1987, p. 1.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Koon 2015, pp. 79–87.

- ^ Koon 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Rawlings 2015, p. 305.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Bagnall 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 240.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 70, n. 76.

- ^ Hoyos 2015, p. 107.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Koon 2015, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 53.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 179.

- ^ a b Jones 1987, p. 29.

- ^ Carey 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 57.

- ^ a b Hoyos 2005, p. 114.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 270.

- ^ a b Bagnall 1999, p. 176.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Lazenby 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Cottrell 1961, p. 98.

- ^ Erdkamp 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 74.

- ^ a b Lazenby 1996, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy 2006, p. 181.

- ^ a b Zimmermann 2015, p. 285.

- ^ Erdkamp 2015, p. 72.

- ^ Zimmermann 2015, p. 284.

- ^ Lazenby 1996, p. 60.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Liddell Hart 1967, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Fronda 2015, p. 244.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy 2006, p. 190.

- ^ Lomas 2015, p. 243.

- ^ Lazenby 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 279.

- ^ Ñaco del Hoyo 2015, p. 377.

- ^ Miles 2011, p. 310.

- ^ a b Miles 2011, p. 315.

- ^ Goldsworthy 2006, p. 222.

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Briscoe, John (2006) [1989]. "The Second Punic War". In Astin, A. E.; Walbank, F. W.; Frederiksen, M. W.; Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. Vol. VIII (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–80. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Carey, Brian Todd (2007). Hannibal's Last Battle: Zama & the Fall of Carthage. Barnslet, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-635-1.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Cottrell, Leonard (1961). Hannibal: Enemy of Rome. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. OCLC 1176315261.

- Edwell, Peter (2015) [2011]. "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2015) [2011]. "Manpower and Food Supply in the First and Second Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2015) [2011]. "Hannibal: Tactics, Strategy, and Geostrategy". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 242–259. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2001). Cannae. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35714-7.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006) [2000]. The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2005). Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247–183 BC. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35958-0.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Jones, Archer (1987). The Art of War in the Western World. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01380-5.

- Koon, Sam (2015) [2011]. "Phalanx and Legion: the 'Face' of Punic War Battle". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 77–94. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Lazenby, John (1998). Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War. Warminster, Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-080-9.

- Liddell Hart, Basil (1967). Strategy: The Indirect Approach. London: Penguin. OCLC 470715409.

- Lomas, Kathryn (2015) [2011]. "Rome, Latins, and Italians in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 339–356. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Mahaney, W. C. (2008). Hannibal's Odyssey: Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Ñaco del Hoyo, Toni (2015) [2011]. "Roman Economy, Finance, and Politics in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 376–392. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Rawlings, Louis (1996). "Celts, Spaniards, and Samnites: Warriors in a Soldiers' War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement (67): 81–95. JSTOR 43767904.

- Rawlings, Louis (2015) [2011]. "The War in Italy, 218–203". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Sabin, Philip (1996). "The Mechanics of Battle in the Second Punic War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement (67): 59–79. JSTOR 43767903.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History (part 2). Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2015) [2011]. "Roman Strategy and Aims in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 280–298. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

External links

Works related to From the Founding of the City at Wikisource

Works related to From the Founding of the City at Wikisource Media related to Battle of Trebia (218 BC) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Trebia (218 BC) at Wikimedia Commons