Battle of Pandu

| Battle of Pandu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indo-Pakistani war of 1947-1948 and Kashmir conflict | |||||||||

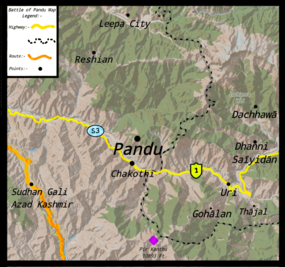

Pandu in Azad Kashmir (Pakistan) on a map | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Tribal commander: |

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 100 Killed[1] |

309 Killed[1] 1 aircraft shot down[11] | ||||||||

The Battle of Pandu,[12] also known as Operation Pandu,[note 2] was a pivotal engagement in the Indo-Pakistani war of 1947-1948. Fought in the Pandu massif along the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad road in Kashmir, the battle centered on control of the strategically important high ground. The Pakistani forces at Chakothi faced a disadvantage to Indian troops on the dominating peaks,[14] The Indian force planned an offensive towards Muzaffarabad through Pandu.[15] Having earlier lost key positions in Pandu to an Indian offensive, Pakistan launched a counter-operation to retake the area, ultimately led to the capture of the Pandu area.[16]

After the unsuccessful summer offensive towards Muzaffarabad from Pandu, the Indian forces launched preparations for a new offensive originating from Jammu. This operation aimed to push westward and northward to relieve Poonch and other areas from Pakistani control.[17] Lieutenant General Bajwa of the Indian Army acknowledged the Pakistani forces for holding their positions. These posts, currently under Pakistani control, offer a strategically advantageous view of the Uri valley in Indian-administered Kashmir, south of the Jhelum River.[18]

Background

Geography

The Jhelum River plunged 3,000 feet to the Indian troop's right, while a carved road snaked along the opposite bank, nestled against hills that rose between 7,000 and 8,000 feet. Turning left, Nanga Tek, a towering peak reaching 10,000 feet, dominated the view. Further along, Rosi Kuta stood at 11,500 feet, with Sing, a slightly closer peak at 10,500 feet. Finally, directly ahead, a long mountain range paralleled the river. Within its folds lay the village of Pandu, often shrouded in mist or rain clouds. This enigmatic presence added to the imposing character of the surrounding mountain stronghold.[19][20] Point 6873 and Pandu peak (9,178 feet), also known as the Pandu feature, on the eastern side are the two notable features. Below the peak the Pandu village resides in a saddle formation. Chhota Kazinag and Chinal Dori and the Pandu saddle is connected via a ridge. Towards the Jhelum River southern slopes drop sharply at 6,000 feet with dense pine forests blanket the massif.[21]

Military situation

In August 1947, tensions rose in Jammu and Kashmir. The region, with a Muslim-majority population, was ruled by a Hindu Maharaja.[note 3] The Maharaja's delay in choosing to accede to either Pakistan or India sparked unrest.[23][24] The conflict escalated with the arrival of armed groups from the North-West Frontier Province. These groups took control of the western parts of the state. On 27 October India intervened militarily in Kashmir, reportedly in response to a request from the Maharaja.[25] The irregular independence fighters were no match for a professional army, and the Indian force's quickly gained major territory. As they moved into Muzaffarabad in May 1948, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan's government directed the Pakistan Army to counter the Indian offensive, which constituted a direct threat to Pakistan.[26]

Prelude

In the latter part of 1947, estimates suggested that the Indian military presence in Kashmir had grown significantly, potentially reaching 90,000 troops.[27] In a summer offensive, Indian forces launched a two-pronged attack on Muzaffarabad via the Jhelum and Kishenganga (Neelum) River Valleys. The Indian 19th Division in Srinagar, consisting of three brigades, was tasked with capturing the town. Following the capture of Tithwal, the 163rd Brigade stationed at Handwara was to advance along the Kishenganga River.[28] The 77th Parachute Brigade at Mahura aimed to secure the high ground north of the Jhelum River, while the 161st Brigade planned to push along the Uri-Muzaffarabad route on the river's left bank. Up to this point, the Pakistan Army's involvement had been limited to supporting independence fighters. However, perceiving a direct threat posed by the Indian advance, General Sir Douglas Gracey, Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army, advocated for military engagement.[29]

Douglas Gracey quoted:-

An easy victory of the Indian Army, particularly in the Muzaffarabad area, is almost certain to arouse the anger of tribesmen against Pakistan for its failure to render them more direct assistance and might well cause them to turn against Pakistan[30]

— (Security Council S/P.V. 464, p. 29, 8 Feb. 1950).

The control of Muzaffarabad hinged on the forces stationed at Chakothi. This position, in turn, was vulnerable to attack from the heights of Pandu and Chhota Kazinag to the north and the forward spurs of Pir Kanthi to the south. On 24 May the Indian 77th Parachute Brigade captured Chhota Kazinag.[31] The same day, a Baloch patrol scouting Pandu detected an opposing force's presence. Reacting swiftly, they secured Point 6873 at the western edge of the massif. However, heavy fighting erupted on 29 May as Indian forces attempted to take control of Point 6873 from the Baloch regiment.[32] Following their occupation of the Pandu massif, Indian forces gained a direct view of Chakothi, where Lieutenant Colonel Bashir Ahmad's 1/13th FF Rifles regiment had established defensive positions.[33] Indian forces launched determined attacks on Chakothi, supported by artillery and airstrikes but they were unable to dislodge the defenders.[34] Unable to make a breakthrough on the frontal approach, Indian forces attempted to outflank Chakothi from the north. This maneuver was met with resistance from the 2nd (Muzaffarabad) Battalion, the 4th FF Rifles, and the Azad Battalion (now known as the 2nd AK Battalion).[32][35]

In response to the tense situation, the brigade commander employed a strategy of flanking and rear attacks to disrupt Indian forces. A company from the Baluch regiment, led by Captain Mohammad Akram, along with a platoon commanded by Subedar Kala Khan, and elements of the 4th Azad Battalion, executed successful operations against the Indian force's left flank. Additionally, irregular forces increased their activity behind enemy lines, leading to the dispersal of the Indian forces.[36] Early June saw the Khyber Rifles establish a presence within the Kandar Kuzi Forest. Operating from this position, they conducted ambushes that hampered the movement of opposing forces and facilitated intelligence gathering. An engagement occurred near Khatir Nar on 19 June, involving the Khyber Rifles and a contingent from the Baluch regiment, against a group from the Indian forces. The encounter resulted in 15 casualties. By the end of June, the summer military campaign was winded down.[37] Forces opposed to Indian control launched a final maneuver to encircle Chakothi from the south.[38] This flanking maneuver required the redeployment of two battalions from the Indian 77th Parachute Brigade, consequently weakening their defenses in the Pandu area. On 29 June, Indian forces captured Pir Kanthi, which threatened both Chakothi and Bagh.[39] In response, Brigadier Akbar Khan decided to capture Pandu.

Plan

To capture Pandu

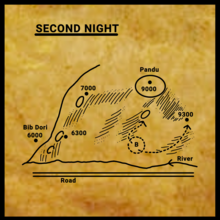

The capture of Pandu presented a significant obstacle. Brigadier Akbar Khan recognized the importance of achieving surprise for a successful outcome. Recognizing a frontal assault would be ineffective, Lieutenant Colonel Harvey-Kelly, Commanding Officer of the 4th Baluch Regiment, devised a well-conceived plan for taking Pandu.[40] The attack plan involved two columns of Baluchi troops advancing from the south, a challenging but potentially surprising approach. The right column, led by Major A.H. Afridi, comprised Delta Company of the 4th Baluch Regiment and Charlie Company of the 17th Baluch Regiment (now known as the 19th Baloch Regiment) under Captain Said Ghaffar Khan. Their objective was to capture Pandu Peak. The remaining forces of the battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Harvey-Kelly, would focus on capturing Pandu itself. To further isolate the Indian 2 Bihar regiment and prevent reinforcements from other Indian units in the area, a two-pronged infiltration operation was planned behind enemy lines. Captain Khalid Khan's Mahsud lashkar from Bib Dori would secure Point 6873, effectively cutting off the Indian forces stationed there from rejoining their battalion at Pandu. Simultaneously, a combined force consisting of one company from the 2nd Azad Battalion and tribesmen led by Captain Qudrat Ullah from Nanga Tak would capture Chham, establishing a blocking position between Khatir Nar and Sing.

The second prong of the infiltration operation involved a larger force under Major Karamat Ullah of the Khyber Rifles from Nardajian. This group comprised two companies from the 2nd Azad Battalion, two platoons from the Khyber Rifles, and two lashkars. Their objective was to reach Sufaida Forest and isolate the 2nd Bihar regiment from the 2nd Dogra regiment.[41] This complex operation demanded meticulous planning and coordination. However, on 17 July 1948 the British government recalled all British officers serving in Kashmir. This decision followed the death of Major A.M. Sloan in the Tithwal Sector on 10 July. Lieutenant Colonel Harvey-Kelly, who had devised the plan for capturing Pandu, was reassigned away from the Pakistani General Headquarters and subsequently withdrew all British officers from Kashmir in accordance with the orders, albeit with reservations.[42][41] Lieutenant Colonel Malik Sher Bahadur assumed command of the battalion in his place.

Reconnaissance mission

Pandu's defenses consisted of approximately half a battalion. Major Akbar Khan of the Pakistani forces estimated that a force of one and a half battalions would be necessary to secure Pandu. However, he was only able to assemble one and a half battalions for the assault. Due to the need for a reserve force, only one battalion would be directly involved in the attack, giving the defenders a two-to-one advantage.[43] The Pakistani forces spent several days preparing for the attack. This included transporting additional ammunition and supplies across the Jhelum River using a rope line erected by sapper. The rope system could ferry either two soldiers or up to 300 pounds of supplies in a single basket.[44]

Once across the river, additional manpower was required to transport supplies. Roughly 2,000 porters were recruited to assist with this logistical challenge. The Pakistani artillery was also repositioned closer to its intended targets. However, the Indian forces possessed a significant advantage in terms of artillery firepower, with an estimated 3,000 shells available to them compared to the Pakistani forces' 900.[44] Three hundred Mahsud tribesmen were available to participate in the operation. These men were organized into three lashkars, each with at least one hundred members. The first lashkar was assigned harassing duties, while the third, designated L3, would be responsible for pursuing the enemy in the event of a successful push. To facilitate movement across the stream near Bib-Dori, a wooden bridge was constructed and completed on the final night. By 17 July the Pakistani forces were prepared to execute their plan.[45]

Battle

1st day

Following nightfall the next day, 18 July,[note 4] a Pakistani battalion discreetly entered the Indian sector, when they went across the stream. The unpreventable sounds were masked by the rain, but also set back further progress.[34] The Pakistani troops established their concealed forward position and Communication was maintained with the headquarters as the troops advanced with the use of telephone lines with addition to wireless communication sets, however they were to be used in urgent situation.

2nd day

On the second day of the operation the Pakistani troops next advance was planned for the evening hours. To maintain radio silence, Pakistani artillery remained silent, avoiding any indication of imminent activity and took cover within their base until twilight.[47] Meanwhile at multiple locations at that morning, Scouts, Azad forces, and tribesmen were deployed by Brigadier Akbar Khan to carry out small harassing raids. Due to cloudy skies and rain throughout the day, Indian aircraft were absent from the area.[34] These operations were intended to be low-key and not arouse suspicion.[48] The harassing parties would successfully engage with the Indian troops without complications, with only one near miss.[47]

However a mishap occurred, when the Pakistani forces local guide slipped in the mud and was captured by Indian troops. The Pakistani troops quickly withdrew from the area.[47] The guide was taken to the Indian headquarters in Pandu, he was interrogated extensively but revealed no information. While tensions ran high, the Indian forces eventually stood down by evening. Meanwhile, the Pakistani forces prepared to execute their next move that night.[47]

3rd day

At dawn the following day, the right column successfully secured their objective, a 9,300-foot mountain overlooking Pandu Lake. The Indian forces responded quickly with a counter-attack, but it was unsuccessful.[49] By afternoon, the right column had advanced to within 500 yards of Pandu, awaiting the left column's progress. The operation unfolded according to plan, exceeding Brigadier Khan's expectations. With the right column in position, the scene was set for the assault on Pandu.[50]

The left column's advance was delayed. The path proved to be extremely challenging, and their telephone wire drums had rolled down the slope in the darkness, severing communication after midnight. Subsequently, they suffered thirty casualties after inadvertently entering an Indian position called Kewa and engaging in a close-quarters battle at night.[51] The Pakistani command remained unaware of the setbacks they had encountered.[52] By daybreak, they were still a considerable distance from their objective and faced heavy shelling as their movements were no longer concealed. Despite these difficulties, they continued their arduous advance until they were further disrupted by a group of fleeing Indian soldiers who ran through their midst.[53]

The Left Column encountered difficulties during its advance, leading to a breakdown in unit cohesion during the night. Discouraged and fatigued, soldiers lost contact with their officers.[54] Despite attempts to halt it, the entire Left Column disengaged around midnight and returned to their starting position near Bib-Dori by 4:00 am. Individual soldiers began to withdraw without orders, and this grew into a larger unauthorized retreat. Observing the Left Column's withdrawal at dawn, the harassing parties, Azads, Scouts, and tribesmen, also retreated, assuming the operation had been called off.[55]

4th day

On the morning of the fourth day, the right-most column, almost half a battalion, remained the only Pakistani force in the forward position. Who were isolated on a 9,300-foot peak within indian territory, faced hostile artillery and aircraft attacks. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, Major Akbar Khan began reevaluating his strategy.[56] The harassing parties resumed their original missions with the aim to disrupt Indian forces and maintain uncertainty amongst the Indian forces until the following day.[56]

5th day

On the morning of the fifth day, reinforcements arrived and joined the right-most column.[57] An imminent military operation was planned near Pandu. The objective involved encountering a reduced Indian force stationed there, with only half a battalion present. This strategy aimed to exploit a temporary numerical advantage by deploying a full battalion from the opposing side, creating a potential two-to-one advantage at a crucial point in the conflict. However, this plan ultimately went unrealized. As a result, the Pakistani forces no longer held the anticipated numerical advantage over the Indian defenders.[58]

Indian troops withdrew from their positions and reinforced the garrison at Pandu, which gave them a numerical advantage over the Pakistani forces. Recognizing the disparity in strength, the Right Column Commander anticipated the attack being called off.[58] Determined to act, Akbar khan ordered a bayonet charge led by officers on (Dehli)[note 5] to leave no room for doubt or hesitation, he based this decision on his belief that the Indian forces were now confused, a state of mind unknown to him at the time.[59]

During earlier operations, harassing parties advancing under the cover of darkness mistakenly believed Indian forces were retreating. One tribal lashkar engaged in a nighttime skirmish after mistakenly entering Pandu itself. The resulting gunfire prompted another lashkar to approach from the opposite direction, leading to another clash.[59] These minor skirmishes, however, appeared to be interpreted by the Indian forces as full-scale attacks. Anticipating the right column's attack the following day, Pakistani troops disregarded usual caution and lit fires for warmth within the jungle. These fires were soon spotted by Indian troops, who perceived them as a surrounding ring. According to a local witness, the Indian forces, believing themselves encircled, spent a tense night and decided to withdraw at daybreak, seeing it as their only option.[60]

Major Akbar Khan believed they had instilled fear in the Indian forces by minor skrimishes. Despite their numerical superiority, equipment, and air support, the Indian forces opted to withdraw.[61] The indian forces launched a sustained and heavy shelling barrage to obscure their movement as they abandoned Pandu and retreated into the dense jungle. When the right column advanced for the assault, Indian troops had already gone.

Fall of Pandu

Upon hearing that the Indian force had given up, Akbar Khan dispatched another lashkar in pursuit across the Indian force's who retreated. Other tribesmen in the vicinity of Pandu also joined the chase.[62] The Indian troops had been routed in confusion and fled down the slopes into the dense jungle. The tribesmen pursued them for twenty-four hours, primarily engaging in close-quarter combat with daggers. The Indian forces suffered significant casualties, estimated at three hundred. When the tribesmen returned, many were clad in captured Indian uniforms and carrying a substantial amount of enemy weapons, ammunition, and other equipment.[63]

The Pakistani forces captured a significant amount of Indian supplies, including approximately 130 rifles and their ammunition.[64] Additionally, they seized stockpiles containing roughly half a million rounds of ammunition, two large mortars, fourteen mortars of various sizes, a machine gun, and around one thousand mortar and artillery shells. A large ration depot was also secured. With the capture of Pandu, a critical strategic point, the remaining Indian defenses crumbled rapidly.[65] As Pakistani forces advanced towards the remaining two companies defending Sing (10,500 feet), those forces also withdrew from the position. Scouts and Azads operating in the area pursued them. A general advance then commenced, and after twelve hours, Pakistani troops reached a position just 200 yards from Chota Kazi Nag (10,000 feet), the final and highest peak in this range. This peak overlooks the Indian communication lines between Baramula and Uri (General Headquarters), at this point, Pakistani forces received orders to halt their advance.[65]

Action of 3 October 1948

In early July 1948, Pakistani forces in Chinari received their first two 40 mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns. These guns fired lightweight shells and had a limited effective range, along with a restricted field of view. Consequently, Indian aircraft initially enjoyed a significant advantage in the airspace. However, the effectiveness of these anti-aircraft guns in engaging aircraft is not well documented.[66] General Akbar Khan would prepare a trap for the Indian aircraft to be shot down.[67]

Khan directed the deployment of the anti-aircraft guns in locations that would maximize their range against Indian aircraft. A medium gun, firing 90-pound shells, was positioned furthest forward under the Chakoti ridge.[67] Additionally, twelve machine guns and sixteen Bren light machine guns were placed on the highest points, around 9,000 feet, to provide supporting fire. An artillery officer was stationed on the peak of the Pandu feature, at an elevation of 9,300 feet, offering a clear view of the Uri camp to monitor weather conditions to assess potential Indian aircraft activity and to signal the presence of aircraft to the troops.[68]

The Indian force's aircraft flew overhead but remained beyond the effective range of the Pakistani anti-aircraft defenses. On the following day, 3 October, three aircraft appeared in the area, seemingly intent on attacking Pandu, Pakistani troops began shelling the camp.[11] As they approached, the aircraft maneuvered by diving and circling. One aircraft sustained damage from machine gun fire and crashed. The pilot ejected safely using a parachute and was subsequently rescued by Indian forces.[69]

Aftermath

Conclusion of the battle

The Indian Air Force played a significant role in the conflict, due in part to the lack of a comparable air force and anti-aircraft defenses by Pakistani forces for a substantial period. This imbalance granted the Indian Air Force dominance in the airspace, impacting logistical operations and potentially influencing other activities across Kashmir.[66] The Indian forces suffered around 309 casualties during the battle, while Pakistani losses were approximately 100. The capture of Pandu marked a significant victory for Pakistan, which effectively eliminated the immediate Indian threat to Muzaffarabad. However, clashes continued in other areas.[1] Following the unsuccessful summer offensive towards Muzaffarabad, Indian forces launched preparations for a new offensive originating from Jammu. This operation aimed to push westward and northward to relieve Poonch and other areas from Pakistani control.[17][70]

The loss of Pandu was a serious setback. Coming as it did after the loss of the positions across the Kishanganga in Tithwal area, it showed the dangers of self-complacency. The temper of the enemy was unmistakable. He was becoming more and more aggressive Two major victories in quick succession helped to raise his morale considerably.[71]

— S.N Prasad, History of Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947-48, Pg: 206

The Indian force's then Planned the following operations:-

- Operation Duck and Bison (To capture Kargil and link-up with Leh)[72]

- Operation Easy (Link up Poonch from Rajauri)[72]

- Operation Camel (To capture Haji-pir pass and link-up with Poonch from south)[72]

In late December 1948, heavy snowfall in the Uri Sector caused significant logistical challenges for the Indian Army. After consulting with General Thimayya, Brigadier Henderson Brooks made the decision to withdraw troops from the Pir Kanthi and Ledi Galli and surrounding areas on 28 December.[18] This cautious move aimed to preserve troop strength. However, on 30 December the 3rd Battalion (3 AK Battalion) recaptured strategically important villages in the Neja Galli area of the Pir Panjal Heights, which had been previously captured by Indian forces. When Indian troops returned to the area by the evening of 1 January, they faced heavy gunfire and found the Pakistani flag raised there. This territory, which provides a strategic view of the Uri Valley from the south bank of the Jhelum River, has remained under Pakistani control.[18][73]

Awards and trials

India

Following the withdrawal of 2 Bihar Battalion from Pandu, Lieutenant Colonel Tur, the Indian unit commander, was arrested by Brigadier Henderson Brooks and subsequently court-martialed. General Thimmaya held Lieutenant Colonel Tur accountable for the loss of Pandu to Pakistani forces.[74]

Pakistan

Major A.H. Afridi was termed the Victor of Pandu along with his subordinates Captain Ghaffar Khan and Lieutenant Khan Zaman by the official Pakistani history, but they received no recognition or award for their great contribution. Generals like Rafiuddin Ahmed recognized their role in the war, expressing shock over it.

General Rafiuddin Ahmed wrote in his book:-

For unknown reasons the two gallant company commanders do not seemed to have received their well deserved recognition[8]

— Rafiuddin Ahmed, History of the Baloch Regiment: 1939-1956

His company was only 50 yards away from the fortified enemy position as the Indian Army's soldiers begin mortar shelling his positions, and received orders to lead the attack on the left side of the bunker where the shelling took place.[75] Moving towards the new position, his passage was jammed due to barbed wire and he decided to advance to cut the wire, taking six men with him.[75] During the firefight, Sarwar used a bolt cutter to cut the wire, and took a bullet from machine gun fire.[75] On 27 July 1948, Captain Sarwar was killed while clearing the passage from the wires.[6] Captain Sarwar Khan of Pakistan was then awarded the Nishan-e-Haider which is the highest military award of Pakistan.[76]

Popular culture

The Pakistani forces used the term "Pandu" to refer to the entire region generally. They assigned the code name "Delhi" to Pandu and later learned from Indian documents that the Indian forces had nicknamed it "Karachi." This highlighted the strategic significance both sides placed on Pandu's local tactical importance. The area also held high value for the local population. Local legend recounts how a Mughal emperor's army was stalled here centuries ago, forcing the Mughals to retreat over the Pir Panjal Pass. This tradition instilled a superstitious belief among the locals that Pandu was unconquerable.[77]

See also

- Operation Datta Khel

- Siege of Skardu

- Battle of Muzaffarabad

- Operation Bison and Duck

- Battle of Chunj

Sources

Footnotes

- ^ Major General Akbar khan had disguised himself under the name General Tariq during the war and took over the command after Khurshid Anwar was injured.[4]

- ^ Battle of Pandu's codename was Pandu operation.[13]

- ^ In India, a Hindu prince who is ranked higher than a raja is known as a maharaja or maharajah. When the term "maharaja" was used throughout history, it referred solely to the head of one of India's major native states. Maharani is the feminine form (maharanee).[22]

- ^ The Author in his book states they executed the plan next day after mentioning they were done gathering equipments for the battle on 17 July, making it clear that the operation on begun 18 July.[46]

- ^ The word (Dehli) was set as codename by Pakistani troops to refer Pandu and on the other side (Karachi) was the Indian codename to refer Pandu. See Popular Culture for Further info.

Citations

- ^ a b c d Javaid 2023, p. 15.

- ^ a b Singh 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Sinha 1977, pp. 83–84 : Praval 1976, p. 185 : Khan 1975, pp. 138–142 : Singh 2010, p. 185

- ^ "General Tariq and the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case - II". The Friday Times. 2021-01-08. Archived from the original on 2024-03-19. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ Gulati 2000, p. 339.

- ^ a b Singh 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Ahmed 1998, p. 221.

- ^ a b Ahmed 1998, p. 295.

- ^ Prasad 1987, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Singh 2010, p. 181.

- ^ a b Singh 2010, p. 189.

- ^ Qadri, Colonel Azam (2024-03-04). "They Led from the Front". hilal.gov. Archived from the original on 2024-03-01.

- ^ Khan, Babar (2023-08-17). "Second in command". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2024-03-17. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 126–127 :

- ^ Prasad 1987, pp. 180–183 : Sinha 1977, pp. 31–33 : Sinha 1977, p. 87

- ^ Sinha 1977, pp. 83–84 : Praval 1976, p. 185

- ^ a b Khan 1975, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Bajwa, Lt Gen JS. Indian Defence Review (Oct-Dec 2018) Vol 33.4. Lancer Publishers LLC. ISBN 978-1-940988-41-2.

- ^ Ahmed 1998, p. 217.

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Javaid 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (2024-03-16). "Maharaja | Indian Ruler, Royalty & Monarch | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2024-02-05. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ Prasad 1987, p. 12

- ^ "643 Christopher Snedden, The forgotten Poonch uprising of 1947". www.india-seminar.com. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ^ "Maharaja Hari Singh's Letter to Mountbatten". www.jammu-kashmir.com. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Javaid 2023, p. 10.

- ^ Lamb 1997, p. 197 : Sinha 1977, p. xiv

- ^ Sinha 1977, p. 70.

- ^ Javaid 2023, p. 10 : Khan 1975, pp. 100–101

- ^ Nations, United (1950). "Security Council official records, 5th year :: 464th meeting 8 February 1950, New York". Security Council Official Records, 5th Year :: 464th Meeting 8 February 1950, New York: 29 – via digitallibrary.

- ^ Sinha 1977, pp. 72–74 : Singh 2010, p. 180

- ^ a b Lt Col Rifat Nadeem Ahmad, History of the Baloch Regiment (Abbottabad: Baloch Regimental Centre, 2017), p. 147.

- ^ Sinha 1977, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Sinha 1977, p. 75.

- ^ Javaid 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Sinha 1977, p. 77.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 118.

- ^ Prasad (1987), p. 188

- ^ Lamb 1997, pp. 241–243

- ^ a b Javaid 2023, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Ahmed 1998, p. 217

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 129.

- ^ a b Khan 1975, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 130.

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c d Khan 1975, p. 132.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 132

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 134

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 134.

- ^ Javaid 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 134

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 135 : Javaid 2023, p. 14

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 135.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 135 : Prasad 1987, p. 205 : Javaid 2023, p. 14

- ^ a b Khan 1975, pp. 135–136

- ^ Ahmed 1998, p. 222

- ^ a b Khan 1975, pp. 137–139.

- ^ a b Praval 1976, p. 185.

- ^ Praval 1976, pp. 182–185 :

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Khan 1975, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Praval 1976, p. 185 : Prasad 1987, p. 206

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 140.

- ^ a b Prasad 1987, p. 206.

- ^ a b Khan 1975, p. 143.

- ^ a b Khan 1975, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 144.

- ^ Singh 2010, p. 189 : Khan 1975, pp. 143–145

- ^ Sinha 1977, pp. 80–102.

- ^ Prasad (1987), p. 206

- ^ a b c Sinha 1977, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Singh Ahlawat 2013, p. 76.

- ^ Prasad 1987, pp. 212–213

- ^ a b c Mirza 1947, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Captain Sarwar Shaheed, Pakistan's first ever Nishan-e-Haider award recipient remembered Pakistan Today (newspaper), Published 27 July 2016, Retrieved 4 November 2018

- ^ Khan 1975, p. 127

Works Cited

- Ahmed, Rafiuddin (1998). History of the Baloch Regiment: 1939-1956. Baloch Regimental Centre. Archived from the original on 2009-12-09.

- Gulati, M. N. (2000). Military Plight of Pakistan (Hardcover). Manas Publications. ISBN 9788170491231.

- Khan, Akbar (1975). Raiders in Kashmir. National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- Lamb, Alastair (1997). Incomplete Partition The Genesis of the Kashmir Dispute 1947-1948 (Paperback). Roxford. ISBN 9780907129080.

- Prasad, Sri Nandan (1987). History of Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947-48. History Division, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2017-01-17.

- Praval, K. C. (1976). Valour Triumphs A History of the Kumaon Regiment. Thomson Press (India). Archived from the original on 2023-06-03.

- Sinha, S.K. (1977). Operation Rescue Military Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947-49. Vision Books. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20.

- Singh, Brig Jasbir (2010). Combat Diary (Hardcover). Amber Books Limited. ISBN 9781935501183.

- Singh Ahlawat, Sube (2013). An Infantry Battalion in Combat A Critical Appraisal of Battle Situations Encountered by an Infantry Battalion (Hardcover). Lancer. ISBN 9781935501367.

- Javaid, Hassan, ed. (2023). "9-Bugle-Trumpet-Summer-2023.pdf". 9-Bugle-Trumpet-Summer-2023.PDF. v (summer 2023). Archived from the original on 2024-02-22 – via Aimh.gov (Army Website).

- Mirza, Yaqub (1947). The golden jubilee celebrations of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Karachi, Sin. Pakistan: National Book Foundation. ISBN 9789693701784.

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (2015) [first published 1979 by Ferozsons], Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2, Mirpur: National Institute Kashmir Studies, archived from the original on 2021-03-29