Battle of Hernani

The Battle of Hernani is the name given to the controversy and heckling that surrounded the 1830 performances of Victor Hugo's Romantic drama Hernani.

Heir to a long series of conflicts over theatrical aesthetics, the Battle of Hernani, which was at least as politically motivated as it was aesthetically, remains famous for having been the battleground between the "classics", partisans of a strict hierarchy of theatrical genres, and the new generation of "romantics" aspiring to a revolution in the dramatic art and grouped around Victor Hugo. The form in which it is generally known today, however, depends on the accounts given by witnesses of the time (Théophile Gautier in particular, who wore a provocative red vest to the Première on 25 February 1830), blending truth and legend in an epic reconstruction intended to make it the founding act of Romanticism in France.

A century and a half of fighting for the theater

Breaking out of the classical straitjacket: towards romantic drama

Criticism of classicism in theater under the Ancien Régime

The battle against the aesthetic dogmas of classicism, with its strict rules and rigid hierarchy of theatrical genres, began as early as the 17th century, when Corneille's prefaces attacked the restrictive codifications established by the doctrines of Aristotle, or with the "great comedy" invented by Molière with his plays in five acts and in verse (i.e., in the usual form of tragedy), which added moral criticism to the comic dimension (Tartuffe, The Misanthrope, The School for Wives...).[1]

In the following century, Marivaux accentuated this strong subversion of genres by grafting a sentimental dimension onto the farcical structure of his plays.[2] But it was with Diderot that the idea of a fusion of genres in a new type of play emerged, an idea he was to develop in his Entretiens sur "le Fils naturel" (1757) and his Discours sur la poésie dramatique (1758): considering that classical tragedy and comedy no longer had anything essential to offer contemporary audiences, the philosopher called for the creation of an intermediate genre: drama, which would submit contemporary subjects of reflection to the public.[3] As for Beaumarchais, he explained in his Essai sur le genre dramatique sérieux (1767) that bourgeois tragedy offered contemporary audiences a morality both more direct and more profound than the old tragedy.[4]

A new level was reached by Louis-Sébastien Mercier in two essays: Du théâtre ou Nouvel essai sur l'art dramatique (1773) and Nouvel examen de la tragédie française (1778). For Mercier, drama had to choose its subjects from contemporary history, do away with unities of time and place, and above all not confine itself to the private sphere: the usefulness of drama shifted from the realm of individual morality to that of political morality.[5]

Criticism also existed on the other side of the Rhine, notably in Lessing's essay Dramaturgie de Hambourg (1767–1769, translated into French in 1785). For the German theorist, who had translated and adapted Diderot's play Le père de famille,[4] French dramaturgy, with its famous three-unit rule, although it claimed to be inspired by the ancient code, only succeeded in rendering artificial and ill-adapted to contemporary reality rules that flowed naturally from the theatrical practice of their time, and in particular from the presence of the chorus, which, representing the people, "could neither depart from its dwellings, nor be absent from them as much as one can usually do by simple curiosity".[6]

Romantic theorists

After the French Revolution, criticism again came from Germany, with Madame de Staël's book titled De l'Allemagne (1810). In it, she established the existence of two theatrical systems in Europe: the French system, dominated by classical tragedy, and the German system (in which she included Shakespeare), dominated by historical tragedy.[7] The French system, she explained, with its choice of subjects drawn from foreign history and mythology, could not fulfill the role of "German" historical tragedy, which strengthened national unity by depicting subjects drawn precisely from national history. What's more, French classical tragedy, which had no interest in the people and in which the people had no interest, was by its very nature an aristocratic art form, which further reinforced the social division by doubling it with a division of theater audiences. But if this social division of theatrical audiences was the logical consequence of the structural social division of monarchical society, the great democratic thrust induced by the Revolution condemned this division to disappear, and at the same time rendered obsolete the aesthetic system that had emanated from it.[8]

Guizot's 1821 essay on Shakespeare and, above all, Stendhal's two-part Racine et Shakespeare (1823 and 1825) defended similar ideas, the latter taking the logic of a national dramaturgy even further: If, for Madame de Staël, the alexandrine should disappear from the new dramatic genre, it's because verse banished from the theater "a host of sentiments" and prohibited "saying that one enters or leaves, sleeps or watches, without having to look for a poetic turn of phrase for it",[9] Stendhal rejected it for its inability to capture the French character: "there is nothing less emphatic and more naïve" than this, he explained. Also, "the emphatic alexandrine suits Protestants, Englishmen, even Romans to a certain extent, but not, certainly, the companions of Henri IV and François I".[10] Moreover, Stendhal protested against the fact that the aesthetics of theater in the nineteenth century remained what they had been in the previous two centuries: "In the memory of any historian, never have people experienced, in their morals and pleasures, a more rapid and total change than that from 1770 to 1823; and they still want to give us the same literature!" He continued.[11]

Moreover, Alexandre Dumas, who prided himself on having won "the Valmy of the literary revolution" with his play Henri III, points out that French actors, caught up in their habits, were incapable of moving from the tragic to the comic, as the new writing of Romantic drama demanded. Their inadequacy was obvious when it came to performing the theater of Hugo, in whom, Dumas explains, "the comic and the tragic touch each other without intermediate nuances, which makes the interpretation of his thought more difficult than if he [...] took the trouble to establish an ascending or descending scale".[12]

The preface to Cromwell

In December 1827,[13] Victor Hugo published a major theoretical text in Paris in support of his play Cromwell, which had been published just a few weeks earlier and would be remembered in literary history as the "Preface to Cromwell". Written at least in part to respond to Stendhal's theses,[14] it proposed a new vision of Romantic drama. Admittedly, Shakespeare was still glorified as the synthesis of the three great geniuses Corneille, Molière and Beaumarchais,[15] while the unity of time and place were seen as incidental (the usefulness of the unity of action, on the other hand, was reaffirmed),[16] Hugo echoing Lessing's argument that the vestibules, peristyles and antechambers in which the action of tragedy took place, paradoxically in the name of verisimilitude, were absurd.[17] As for the theory of the three ages of literature (primitive, antique and modern), it was so unoriginal that it has been described as "a veritable 'cream pie' of the literati of the time".[18] What did make the essay original, however, was the centrality of the aesthetics of the grotesque:[19] its alliance with the sublime made it the distinctive trait of "modern genius, so complex, so varied in its forms, so inexhaustible in its creations",[20] and, since this alliance was not permitted by the strict separation of theatrical genres in the classical hierarchy, which reserved the sublime for tragedy and the grotesque for comedy, this hierarchy, unfit to produce works in keeping with the genius of the age, had to give way to drama, capable of evoking in the same play the sublime of an Ariel and the grotesque of a Caliban.[21] The alliance between the grotesque and the sublime should not, however, be seen as an artificial one, imposed on artists as a new dramatic code: on the contrary, it stemmed from the very nature of things, since Man carries both dimensions within himself. Thus, Cromwell was both a Tiberius and a Dandin.[22]

In contrast to Stendhal, Hugo advocated the use of versification rather than prose for Romantic drama: the latter was seen as the preserve of a militant, didactic historical theater that was undoubtedly intended to be popular, and which reduced art to the purely utilitarian. In other words, bourgeois theatre.[23] Verse, on the contrary, seemed to him the ideal language for a drama envisaged not so much as a mirror of nature as a "mirror of concentration" that amplifies the effect of the objects it reflects, making "a glimmer a light, a light a flame".[24] But this verse, which "communicates its relief to things which, without it, would pass for insignificant and vulgar"[25] was not classical verse: it claimed for itself all the resources and flexibility of prose, "capable of traversing the whole poetic range, going from top to bottom, from the most elevated to the most vulgar ideas, from the most buffoonish to the most serious, from the most exterior to the most abstract". He was not afraid to use "the enjambment that lengthens it", which he preferred to "the inversion that confuses it".[26]

This manifesto of Romantic drama was received differently, depending on the age of its readers: "it irritated his elders, his contemporaries loved it, his younger contemporaries adored it", explains Hugo's biographer Jean-Marc Hovasse.[22] For the latter, the play and its preface were almost like a Bible.[22] In 1872, Théophile Gautier recalled that, for those of his generation, the preface to Cromwell "shone in [their] eyes like the tables of the Law on Sinai, and [that] its arguments [seemed to them] without reply".[22] On the other hand, the aesthetics it advocated "definitively distanced Romanticism from the Société royale des Bonnes-Lettres and, consequently, from the government of Charles X".[27]

Disrupted performances

The heckles surrounding theatrical performances—the most famous incarnation of which would be Hernani—began in 1789, with Marie-Joseph Chénier's Charles IX ou la Saint-Barthélémy. There was talk of banning the play, which provoked virulent exchanges between its supporters and detractors. Initially an internal quarrel among French actors, it soon pitted "the patriots against the 'Court Party', the assembly against the king, the Revolution against the counter-revolution".[28] Already in this conflict, the positions of all parties were over-determined by their political convictions. Chénier himself was aware of the ideological significance of the conflict, and of the strategic place of theater, writing in the "epitre dédicatoire" of his play that, "if the morals of a nation first form the spirit of its dramatic works, soon its dramatic works will form its spirit".[29] The play was finally performed in November 1789, with tragedian François-Joseph Talma in the title role. Attending the premiere, Danton was quoted as saying: "If Figaro killed the nobility, Charles IX will kill royalty".[30] Three years later, in January 1793, the performance of Jean-Louis Laya's L'Ami des lois caused an even greater stir: it was the guns of the Commune that forbade performances.[31] Already at this time, heckling was observed to be the work of groups of spectators who had sometimes organized their demonstration beforehand.

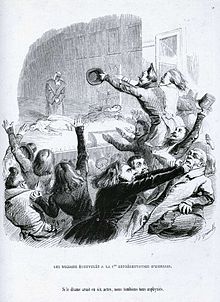

With Christophe Colomb, performed in 1809 at the Théâtre de l'Odéon (then known as the Théâtre de l'Impératrice), playwright Népomucène Lemercier, on the other hand, set out to break away from the unity of time and place, to mix registers (comic and pathetic), and to take liberties with the rules of classical versification: At the play's premiere, the stunned audience didn't react. By the second performance, however, the audience, mostly made up of students hostile to the author's liberties with the classical canons, provoked clashes violent enough for grenadiers to storm the auditorium, bayonets fixed. An audience member was killed, and three hundred students were arrested and forcibly conscripted into the army.[32]

During the Restoration period, the "battles" over theater largely confirmed the victory of the proponents of aesthetic modernity: Victor Ducange and Dinaux's Trente ans ou la vie d'un joueur (1827), which told the story of a man's life through the evocation of three decisive days in his life, was a huge success at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin. For the critic of Le Globe, a liberal newspaper, Trente ans marked the end of classicism in the theater, and he lashed out at the proponents of this aesthetic: "Weep for your beloved unities of time and place: here they are once again vividly violated [...] it's all over with your compassed, cold, flat productions. Melodrama kills them, free and true melodrama, full of life and energy, as M. Ducange does, and as our young authors will do after him.[33] In 1829, Alexandre Dumas triumphed with Henri III et sa cour, a drama in five acts and prose, which he succeeded in imposing on the Comédie-Française.[34] In May 1829, Casimir Delavigne's "semi-romantic" verse tragedy Marino Faliero (inspired by Byron) was a triumphant success, even though in many respects it was no less innovative than Hernani.[35] But it was presented at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, not at the Théâtre-Français, which would be Hugo's fortress to conquer. Finally, if Alfred de Vigny's adaptation of Shakespeare's Othello ou le Maure de Venise was only half a success, it did not cause the uproar that had arisen seven years earlier when a troupe of English actors was forced to perform to the booing and projectiles of the audience (one actress had even been injured).[36] There were, however, a few clashes, mainly linked to the use of a trivial vocabulary deemed incompatible with the use of versification (the word "handkerchief", in particular, was the focus of criticism).[37]

Nevertheless, despite all the battles he had won in the years leading up to 1830, it was up to Victor Hugo to wage a new one, to give pride of place to his own aesthetic, which would bring to the stage of the Théâtre-Français not a work in prose, as Dumas had done, but a drama in verse that would claim for itself the heritage of all the prestiges of tragedy, whether in terms of great style, or the ability of the great classical dramatists to pose the problems of power.[38]

Theaters during the Restoration

A 1791 decree on spectacles authorized any citizen who so wished "to build a public theater and to have plays of all genres performed there".[39] As a result, theatres multiplied in Paris between the Revolution and the Restoration (despite a halt under the Empire). They were divided into two main categories: on the one hand, the Opéra, Théâtre-Français and Odéon, subsidized by the authorities, and on the other, private theaters, which lived solely on their takings.[40] Among the latter, the main venue for disseminating the Romantic aesthetic was the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, where most of Dumas's dramas and several of Hugo's plays would be performed, amid vaudevilles and melodramas.[41]

The most prestigious of official performance venues, the Théâtre-Français, had 1,552 seats (worth between 1.80 and 6.60 francs)[42] and was dedicated to promoting and defending the great dramatic repertoire: Racine, Corneille, Molière, sometimes Marivaux, Voltaire and his neo-classical followers: it was explicitly subsidized for this mission. The subsidy functioned as an auxiliary to censorship: "subsidy is subjection", wrote Victor Hugo in 1872.[43]

Since 1812, the Théâtre-Français had been subject to a special regime: it had no director and was run by a community of members, itself headed by a royal commissioner. In 1830, this commissioner was a man who, as far as possible, supported the new Romantic aesthetic: Baron Isidore Taylor. It was he who enabled Hugo to stage Hernani at the Théâtre-Français.

The Théâtre-Français' main asset was its troupe of actors, who were the best in Paris: they excelled, in particular, in the diction of classical verse.[44] However, when it came to interpreting the new drama, they were no match for the great actors of the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, such as Frédérick Lemaître or Marie Dorval. But, and this would be one of the major problems facing the Romantic playwrights, even if they succeeded in getting their plays accepted by the Théâtre-Français: it would be virtually impossible for them to get their actors admitted at the same time, those who were best able to defend these plays.[45]

Nevertheless, despite the quality of their actors, and despite Baron Taylor's recruitment of the set designer Ciceri, who revolutionized the art of theatrical décor,[46] performances at the Théâtre-Français were staged to near-empty houses, as it was notoriously boring to "listen to pompous declamators methodically reciting long speeches", as an editor of the Globe, a newspaper admittedly unfavorable to the neo-classicals,[47] wrote in 1825. As a consequence of the public's disavowal of a dramatic aesthetic that was no longer in tune with the tastes of the time, the Théâtre-Français' financial situation was calamitous: while a performance cost an average of 1,400 francs, it was not uncommon for receipts to fall below 150 or 200 francs,[48] to be divided into 24 shares, 22 of which went to the actors.[49] As a result, the Théâtre-Français' survival depended directly on the public subsidies it received, unless it was performing romantic plays, which did generate income.[50] Aware of this situation, the Théâtre-Français' main suppliers of new plays, the authors of neo-classical tragedies, petitioned Charles X in January 1829 to forbid the performance of Romantic drama there. The king refused to accede to their request.[51] Hugo could therefore try his luck there.

Victor Hugo in 1830

From Marion de Lorme to Hernani

Marion de Lorme, written in one month in June 1829, had been unanimously accepted by the actors of the Théâtre-Français[52] and was therefore to be the first Romantic drama, in verse as recommended in the preface to Cromwell, to be performed on this prestigious stage. But the censorship board, chaired by Charles Brifaut, decided to ban the play from being performed. Hugo requested, and was granted, a meeting with Viscount of Martignac, Charles X's Minister of the Interior, who had personally intervened to have the play banned.[53] However, despite his reputation as a moderate advocate of the "juste milieu" policy, he refused to overturn the censorship committee's decision: the political situation was delicate, and the staging of a fable that portrayed Louis XIII as a monarch less intelligent than his jester, and dominated by his minister, was likely to inflame the public.[54] All the more so since, since The Marriage of Figaro, it was well known what effect a play could have on the public[55] (Beaumarchais' play had been banned from performance for several years during the Restoration).[56] A meeting with Charles X was no more successful. The play would not be performed. On the other hand, Hugo was offered to triple the amount of the pension he received from the king. He scornfully refused this conciliatory proposal. And so he set to work writing a new play.

Time was of the essence: Dumas' Henri III had already triumphed at the Théâtre-Français, and Vigny was about to stage his adaptation of Othello. The author of the preface to Cromwell could not afford to take a back seat and leave the limelight to playwrights who, although friends of his, were nonetheless rivals threatening Victor Hugo's dominant position from within his own camp.[22]

Hugo then set about writing a new drama, this time set in Spain, but which, despite (or thanks to)[57] this strategic geographical shift, would be even more politically dangerous than Marion de Lorme.[58] It would no longer describe the end of Louis XIII's reign, but the advent of Charles V as emperor: even more than Cromwell, Don Carlos would evoke Napoleon.[58]

Written just as quickly as Marion de Lorme (between 29 August and 24 September 1829),[59] Hernani was read to an audience of some sixty of the author's friends, to great acclaim. Five days later, the Théâtre-Français unanimously accepted the play.[52] But the censorship commission still had to give a favorable opinion, which was all the more uncertain as Martignac's moderate government had been replaced by that of the Prince de Polignac. This new government, representative of the most extreme currents in the monarchy, caused a stir even among the royalists: Chateaubriand was stunned and, in protest, resigned as ambassador to Rome.

However, during the Marion de Lorme censorship affair, the press took up Hugo's cause: banning two of his plays in quick succession could prove politically counter-productive. As a result, the censorship commission, still chaired by Brifaut, confined itself to a few remarks, imposing deletions and minor adjustments, notably to passages in which the monarchy was too obviously treated lightly (the line in which Hernani exclaims: "Do you believe, then, that my kings are sacred to me?" caused a stir within the commission).[58] For the rest, the censorship commission's report indicated that, despite the play's abundance of "improprieties of all kinds", it was wiser to allow it to be performed, so that the public could see "how far astray the human mind, freed from all rules and decorum, can go".[60]

The rehearsals

Hernani was ready to be performed on the stage of the Théâtre-Français, by the best actors in the company. As was customary at the time, the roles were cast without taking into account the relationship between the age of the actors and the supposed age of the characters. Thus, Firmin, aged 46, would play Hernani, who was supposed to be 20. Mademoiselle Mars (51) would be dona Sol (17), while Michelot (46) would play don Carlos (19).[61]

As a rule, since the specific function of stage director did not exist (it would appear in Germany, with Richard Wagner),[62] it was the actors themselves who invented their roles and created their effects. As a result, each actor soon specialized in a particular type of role.[63] Victor Hugo, who showed a much greater interest in the materiality of the performance of his work than his fellow playwrights, was involved in the stage preparation of his plays, choosing the cast himself (when he had the opportunity) and directing rehearsals. This practice, which contrasted with usual practice, caused some tension with the actors at the start of work on Hernani.[64]

Alexandre Dumas gave a truculent account of these rehearsals, and in particular of the quarrel between the author and the actress who found ridiculous the line in which she said to Firmin "Vous êtes mon lion, superbe et généreux", which she wished to replace with "Vous êtes Monseigneur vaillant et généreux".[65] This animal metaphor, while not unheard of in classical theater (it can be found in Racine's Esther and Voltaire's[66] L'Orphelin de la Chine), had in fact taken on a juvenile connotation in the first third of the 19th century, which the actress felt was hardly appropriate for her acting partner.[67] Every day, the actress returned to the charge, and every day, unperturbed, the author defended his verse and refused to change it, until the day of the first performance, when Mademoiselle Mars, against Hugo's advice, pronounced "Monseigneur" instead of "mon lion". In fact, it is likely that the actress had persuaded the playwright to make the change, so as not to invite ridicule: it was "Monseigneur", not "mon lion", that was written on the prompter's manuscript.[68]

The cabal against Hernani

If Hernani's opponents were familiar with the "superb and generous lion", it was because part of it had been leaked to the press and published: it was Brifaut himself who, having kept a copy of the text submitted to the censorship commission, had leaked it. And, so that the public could see "how far Hugo had gone astray", they were shown truncated verses. Thus, for example, the line in which dona Sol exclaims: "Venir ravir de force une femme la nuit!" had become: "Venir prendre d'assaut les femmes par derrière!"[69] Hugo wrote a letter of protest against such an obvious breach of the duty of reserve, without much result.[69]

Hugo's enemies were not only the defenders of Polignac's reactionary government: at the other end of the political spectrum, the liberals distrusted the former "ultra", who had begun to draw closer to them at the end of 1829,[70] while making no secret of his fascination with Napoleon.[71] The main organ of the liberal party, Adolphe Thiers' newspaper Le National, fiercely opposed to Charles X, was one of the play's most virulent critics.[72] Hugo's aesthetic opponents, the neoclassical playwrights, were also liberals,[73] and they worked hard to undermine the actors' motivation.[69]

At the time, many thought the play would never make it past its premiere, and tickets for this one-off performance were snapped up.[74] Hugo, for his part, had dealt in his own way with the problem of the "claque", a group of spectators paid to applaud at strategic points in the play, who greeted the performers as they entered and were eventually responsible for expelling unruly spectators. However, the claque was made up of friends and family of the classical playwrights, their regular customers, and was therefore unlikely to support their enemy's play with the enthusiasm they desired.[75] So Hugo decided to dispense with their services and recruit his own claque.

The romantic army

The Romantic claque was recruited from painting and sculpture studios and their students, along with young writers and musicians. They were the ones who, with their eccentric costumes, shaggy hair and macabre jokes, would create a sensation among the polite Théâtre-Français audience.[76] From among the new generation that made up the "Romantic army" at Hernani's performances would emerge the names Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, Hector Berlioz, Petrus Borel and others.[76] All of these were Hugo supporters, either because they agreed with the theses in the preface to Cromwell, or because Hugo was an author who was the target of government censorship. The generational dimension was superimposed on this political dimension: young revolutionaries were opposed to a gerontocratic government made up of former émigrés who had returned from exile "without having learned anything or forgotten anything", as a saying of the time put it,[77] who wanted to see the loss of a play in which it was an old man who condemned young spouses to death.[78]

This group of several hundred people was later named by Théophile Gautier as the "Romantic Army", in an explicit reference to the Napoleonic epic:[79]

"In the Romantic army, as in the Italian army, everyone was young. Most of the soldiers had not reached the age of majority, and the oldest of the bunch was the general-in-chief, aged twenty-eight. That was the age of Bonaparte and Victor Hugo at the time".

Gautier's politico-military metaphor was neither arbitrary nor unprecedented: the parallel between the theater and the City in their struggle against the systems and constraints of the established order, summed up in 1825 in Le Globe critic Ludovic Vitet's lapidary formula ("le goût en France attend son 14 juillet ")[80] was one of the truisms of a generation of literati and artists who looked to the political revolution as their strategic model,[81] and who readily used military language: "The breach is open, we shall pass",[82] Hugo had said after the success of Dumas's Henri III. Before the first performance of Hernani, the "claque" was assembled. Each member received a nominative invitation ticket (Baron Taylor feared that some of them might be resold)[83] in red, on which was written the word Hierro ("iron", in Spanish), which was to be their rallying cry, just as it was the battle cry of the Almogavares in Les Orientales.[84] Hugo is said to have delivered a speech in which aesthetic, political and military considerations were once again intertwined:[84]

"The battle that's about to begin in Hernani is the battle of ideas, the battle of progress. It's a common struggle. We are going to fight this old crenellated, locked literature [...] This siege is the struggle of the old world and the new world, we are all of the new world".

Florence Naugrette, a specialist in Hugolian literature, has shown that in reality this speech was reinvented in 1864.

The story of the "Battle of Hernani"

25 February 1830: the triumph of the Première

On 25 February, Hugo's supporters (including Théophile Gautier, who, out of "contempt for opinion and ridicule",[85] wore his hair long and a famous red or pink vest) were in front of the Théâtre-Français from 1 pm, lining up at the theater's side door, which the Prefect of Police had ordered to close at 3 pm. The prefecture hoped that scuffles would break out, forcing the crowd of non-conformist young people to disperse.[86] The theater's employees did their part to help the forces of law and order, pelting the Romantics with garbage from the balconies (legend has it that Balzac was hit in the face with a cabbage core).[87] But the latter remained stoic and entered the theater before the doors closed on them. They still had four hours to wait in the dark before the rest of the audience arrived. Hugo, from the actors' hole in the stage curtain, watched his troops without showing his face.[88] When the other spectators entered the dressing rooms, they were not a little surprised by the spectacle offered by the Romantic troupe spread out below. But soon the curtain rose. The set depicted a bedroom.

The audience was thus divided between Victor Hugo's supporters, his opponents, and the curious who had come to witness this premiere, which was advertised everywhere as the last of a play about which so much had been said. On this day, it was the former who triumphed. Don Gomez's long tirade in the gallery of portraits of his ancestors (Act III, scene VI), which had been eagerly awaited, had been cut in half, so that Hugo's opponents, taken by surprise, had no time to switch from murmurs to whistles. The "j'en passe et des meilleurs" with which it was brought to an end became proverbial.[89] Don Carlos's monologue in front of Charlemagne's tomb drew rapturous applause; the sumptuous sets of the fifth act impressed the entire audience. At the end of the play, ovation followed ovation, the actors were cheered, and the playwright was carried home in triumph. Years later, Gautier would write:[90]

"February 25, 1830! This date remains written in the depths of our past in flamboyant characters: the very first performance of Hernani! That evening decided our lives! It was there that we received the impetus which still drives us on after so many years, and which will see us through to the end of our career".

That day, takings at the Théâtre-Français were 5,134 francs, or 14,170 euros in 2022. Phèdre, performed the day before, had only brought in 450 francs.[50] Legend has it that, on the evening of the performance, Victor Hugo sold the rights to publish the play to the publisher Mame for 6,000 francs, and that the contract was signed at a café table. In fact, it was on 2 March that Hugo, after some hesitation as to the choice of publisher, allowed Mame to publish Hernani (whose text was significantly different from the one we know today).[91]

Eventful performances

The next two performances were just as successful: it had to be said that Baron Taylor had asked Hugo to bring back his "claque" (who would no longer have to spend the afternoon in the theater), and that no less than six hundred students formed the troupe of the writer's supporters.[89] But from the fourth performance onwards, the balance of power shifted: only a hundred free seats were distributed. The Romantic troupes went from one against three to one against sixteen.[89] What's more, the audience, especially Hugo's opponents, were more familiar with the text of the play, and knew when to whistle.

This audience was not shocked by Hugo's distortions of the classical alexandrine: the enjambment that moves the adjective "dérobé" to the line following the one containing its noun (the famous "escalier") was not as shocking as Gautier claims.[92] In fact, it would seem that even at this time, the public could no longer hear the rhythmic drive of the lines, which meant they were unable to appreciate Hugo's transgressions of classical versification.[93] What did provoke sarcasm and ridicule, however, was the triviality of the dialogue, and the use of vocabulary that had no place in classical tragedy: the absence of periphrasis in doña Sol's "vous avez froid" in the second scene of Act I provoked hisses; dialogue like "Est-il minuit? -Minuit bientôt" between the king and don Ricardo (Act II, scene 1) dismayed him.[94] Hugolian versification did, however, give the audience the opportunity for a huge laugh, in Act I, scene 4: "Oui, de ta suite, ô roi! de ta suite! – I'm in," murmurs a menacing Hernani. But Firmin, well-versed in the habits of classical verse diction, paused at the hemistiche. The result was: "Oui, de ta suite, ô roi! de ta suite j'en suis!" Hugo was forced to rework the verse.

As the days passed, the climate became increasingly hostile. Words were exchanged in the hall between supporters and opponents. Posterity has remembered those of sculptor Auguste Préault, hurled on 3 March at the balding old men before him. He shouted to these men old enough to remember the Terror: "To the guillotine, on your knees!"[95] On 10 March, the audience came to blows, and the police had to intervene.[95] The actors were tired of the whistles, shouts, laughter and incessant interruptions (it has been calculated that they were interrupted every twelve lines, i.e. almost 150 times per performance),[95] and performed their roles with less and less conviction. Hostile and disconcerted, "most of them don't care what they have to say", Victor Hugo complained in his diary on 7 March.

Outside the theater, Hernani was also the subject of ridicule: "absurd like Hernani" and "monstrous like Hernani" became commonplace comparisons in the reactionary press. But the liberal press was not to be outdone: its leader, Armand Carrel, wrote no less than four articles in Le National denouncing the monstrosity of the Hugolian drama, and above all warning the liberal public against the amalgams spread by the author of Cromwell: no, Romanticism was not the expression of liberalism in art, and artistic freedom had nothing to do with political freedom.[96] What really bothered Carrel was the blurring of genres brought about by Hugo's aesthetics: he himself agreed with the "classics" that there was a major theatrical genre for the elite, tragedy, and, to educate the people, a minor and aesthetically less demanding genre, melodrama. Hugo's idea of creating "an elite art for all", a theater in verse for both the elite and the people, seemed dangerous.[97]

The boulevard theaters, meanwhile, amused Paris with their parodies of Hernani: N, i, Ni ou le Danger des Castilles (a romantic amphigouri in five acts of sublime verse mixed with ridiculous prose), Harnali ou la Contrainte par Cor, or, quite simply, Hernani.[98] Don Gomez was renamed Dégommé, dona Sol Quasifol or Parasol...[99] Four parodic plays and three pamphlets (the ironic tone of one of which, directed against "literary cafarderie", shows that it was actually written in Hugo's entourage)[100] were launched in the months following the first performance of the drama.

Not all manifestations of the Querelle d'Hernani were as pleasant as these parodies: a young man was killed in a duel, defending the colors of Victor Hugo's play.[101]

For four months, all performances of the play were heckled.[102] In June, performances became less frequent. By the end of the following month, the battle had left the theater and taken to the streets: the Trois Glorieuses had begun, a revolution of which the Battle of Hernani could later be said to have been the dress rehearsal.[103]

Record

Although the play was a commercial success (grossing no less than 1,000 Francs per performance),[99] and established Victor Hugo as the leader of the Romantic movement while at the same time making him the most famous victim of the increasingly unpopular regime of Charles X,[104] this scandalous success also marked the beginning of a certain disdain among the learned for Romantic drama in general, and Hugo's theater in particular.[105] Note, however, the opinion of Sainte-Beuve: "The Romantic question is carried, by the mere fact of Hernani, a hundred leagues forward, and all the theories of the contradictors are upset; they have to rebuild others afresh, which Hugo's next play will further destroy".[106]

At the Théâtre-Français, after the interruption caused by the July Revolution, the actors were in no hurry to resume performances of Hernani. Believing that they had interrupted them too soon (the play was halted after thirty-nine performances),[107] Hugo sued them, and withdrew their right to perform Marion de Lorme, whose ban had been lifted by the new regime.[108]

Victor Hugo, however, was not done with censorship, which was officially abolished by the Louis-Philippe government: two years after Hernani, Le Roi s'amuse, after a single performance just as stormy as those of Hernani,[109] was banned by the government, on the grounds that "morals [were] outraged".[110] Here again, the criticisms focused not on the versification, which would have been particularly audacious, but on the ethical and aesthetic bias of Hugol's dramaturgy, which equates the sublime and the trivial, the noble and the popular, demeaning the former and elevating the latter in an attack on the socio-cultural code that was often experienced by aristocratic or bourgeois audiences as an aggression.[111] A reviewer for the legitimist journal La Quotidienne was quick to point this out in 1838, on the occasion of another scandal, this time caused by Ruy Blas:[112]

"Let Mr. Hugo make no mistake, his plays find more opposition to his political system than to his dramatic one; they are less resented for scorning Aristotle than for insulting kings [...] and he will always be more easily forgiven for imitating Shakespeare than Cromwell".

From battle to legend

The creators of myth

The discrepancy between the reality of the events surrounding Hernani's performances and the image that has remained of them is palpable: posterity has remembered Mademoiselle Mars's unpronounceable "lion", Balzac's cabbage core, the blows and insults exchanged between the "classics" and the "romantics", the "stolen staircase" on which the classic verse stumbled, Gautier's red vest, and so on, It's a mixture of truth and fiction, which reduces to the date of 25 February 1830 events that took place over several months, and forgets that the first performance of Hugo's drama was, almost without a fight, a triumph for the leader of the Romantic aesthetic. What's more, the legend that has grown up around Victor Hugo's drama, by glossing over earlier theatrical "battles", ascribes to the events of the first half of 1830 a far greater importance than they actually had.[113] The essential elements of this "myth of a cultural Grand Soir"[114] were established as early as the nineteenth century by direct witnesses to the events: Alexandre Dumas, Adèle Hugo and, above all, Théophile Gautier, a relentless hernianist.

Dumas recalls the battle of Hernani in his Mémoires (1852), which includes the famous anecdote of the "superb and generous lion" that Mademoiselle Mars refused to pronounce. He too had a run-in with the actress,[115] and in March 1830, he too encountered difficulties with his play Christine, which was first censored and then, after modifications, had a stormy first performance.[116] Dumas's intention in his Mémoires was to link the reception of the two plays, to give credence to the idea that there had been a "battle of Christine" at the same time as the battle of Hernani, almost reducing the latter "to a quarrel between the author and the actors".[117] Choosing to recount the uproar caused by Christine, Le More de Venise and Hernani, and making his own play the paradigm of the resistance encountered by the Romantic movement, he tends in his Memoirs to play down the significance of the events surrounding the performances of Hugo's play.[117]

While Alexandre Dumas' romantic anecdotes quickly became part of the legend of the Battle of Hernani, it was with his wife Adèle that the legend truly began to take on the epic tone that would be the main characteristic of Gautier's story. This tone is particularly apparent in the unexpurgated text by the playwright's wife, since the story published in 1863 under the title Victor Hugo raconté par un témoin de sa vie (Victor Hugo recounted by a witness to his life), after re-reading by the Hugo clan, was stripped of it, in favor of a novelistic vein that placed it more in the tradition of Dumas.[117]

But the main source for the legend of the Battle of Hernani was Théophile Gautier's Histoire du romantisme, written in the last months of his life, in 1872. The incipit of this story reads as follows:[118]

"Of those who, answering Hernani's horn, followed him up the rugged mountain of Romanticism and so valiantly defended its defiles against the attacks of the classics, only a small number of veterans survive, disappearing every day like the medallists of St. Helena. We had the honor of being enrolled in those young bands who fought for the ideal, poetry and the freedom of art, with an enthusiasm, bravery and devotion no longer known today".

The military metaphor and the parallel with Bonaparte continued in the rest of the story, which also gave pride of place to the picturesque (an entire chapter of the book is devoted to the "red vest"), and above all condensed into a single memorable evening events borrowed from different representations, in a largely idealized evocation of events that would make a lasting contribution to fixing the date of 25 February 1830 as the founding act of Romanticism in France.[117]

The fixed legend

Contemporary perceptions of the play were quickly conditioned by the legendary battle that surrounded its creation. In 1867, while Victor Hugo was still in exile in Guernsey, Napoleon III lifted censorship on the plays of his most famous opponent, and allowed Hernani to be staged again. The audience, mostly composed of young people who only knew about the heckles of 1830 from hearsay, applauded loudly the lines that had been whistled (or were supposed to have been) in 1830, and expressed their disapproval when they didn't hear the expected lines[117] (the text performed was essentially that of 1830, with the modifications made by Hugo after the first performances).[119]

After François Coppée and his poem "La bataille dHernani" (1882), which "radicalized[d] the constituent elements of the battle",[117] Edmond Rostand contributed to the building of the Hernani legend, with his poem "Un soir à Hernani: 26 février 1902", inspired by the stories of Gautier and Dumas.[117] From then on, the true story of the performances of Victor Hugo's play took a back seat to its hagiographic-epic reconstruction: when the Comédie-Française printed a booklet commemorating its great theatrical creations for its tercentenary, the date of 25 February 1830 was not "Hernani – création", as it had done for other plays, but "bataille dHernani”. This battle was re-enacted by and for high-school students in 2002, during the bicentenary celebrations of Victor Hugo's birth,[117] while a TV film by Jean-Daniel Verhaeghe (based on a screenplay by Claude Allègre and Jean-Claude Carrière), La Bataille d'Hernani,[120] helped to reinvigorate the story inspired by the events surrounding the premiere of Victor Hugo's play one hundred and seventy-two years earlier.

Bibliography

Contemporary stories

- Dumas, Alexandre. Mes Mémoires. 1852.

- Gautier, Théophile (1877). Histoire du romantisme.

- Hugo, Adèle (1863). Victor Hugo raconté par un témoin de sa vie.

Excerpts devoted to the battle of Hernani from these three texts, as well as articles by Gautier, letters and notes by Victor Hugo on the same subject, are available online at the Centre Régional de Documentation Pédagogique de l'Académie de Lille, in a dossier created by Françoise Gomez.

Contemporary analysis

Books

- Blewer, Evelyn (2002). La Campagne d'Hernani. Paris: Eurédit.

- Gaudon, Jean (1985). Hugo et le théâtre. Stratégie et dramaturgie. Paris: Éditions Suger.

- Hovasse, Jean-Marc (2001). Victor Hugo, vol. I: Avant l'exil, 1802–1851. Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-61094-8.

- Naugrette, Florence (2001). Le Théâtre romantique. Paris: Seuil.

- Ubersfeld, Anne (1985). Le Roman d'Hernani. Paris: Le Mercure de France.

- Ubersfeld, Anne (1999). Le Drame romantique. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Ubersfeld, Anne (2001). Le Roi et le bouffon. Essai sur le théâtre de Hugo. Paris: José Corti.

Articles

- Gaudon, Jean (1983). "Sur "Hernani"". Cahiers de l'Association internationale des études françaises. 35 (35).

- Laurent, Franck (1999). "Le drame hugolien: un "monde sans nation"?". Rencontres Nationales de Dramaturgie du Havre. éditions des Quatre-vents.

- Roman, Myriam; Spiquel, Agnès (2006). "Hernani, récits de bataille". Communication au Groupe Hugo de l'université de Paris 7.

- Rosa, Guy (2000). "Hugo et l'alexandrin de théâtre aux années 30:une question secondaire". Cahiers de l'Association des Études Françaises. 52 (52): 307–328. doi:10.3406/caief.2000.1396.

- Thomasseau, Jean-Marie (2006). "Le théâtre et la mise en scène au xixe siècle". Histoire de la France littéraire (3). Quadrige.

- Thomasseau, Jean-Marie (1999). "Le vers noble ou les chiens noirs de la prose, Le Drame romantique". Rencontres Nationales de Dramaturgie du Havre. éditions des Quatre-vents.

- Ubersfeld, Anne (1992). Le moi et l'histoire-Le Théâtre en France. Paris: Le Livre de poche.

- Vielledent, Sylvie (1999). "Les Parodies d'Hernani". Groupe Hugo. l'Université de Paris 7.

Telefilm

La Bataille d'Hernani, 2002.

Other

- Hugo, Victor (1985). Œuvres complètes. théâtre I. Paris: Robert Laffont.

- Souriau, Maurice (1973). La préface de Cromwell: introduction, texte et notes. Geneva: Slatkine.

- Ubersfeld, Annie (1968). Introduction. Cromwell. By Hugo, Victor. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion.

Notes and references

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 22)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 23)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, pp. 23–24)

- ^ a b Naugrette (2001, p. 25)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, pp. 14–15)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, p. 32)

- ^ Laurent (1999, p. 11)

- ^ Laurent (1999, p. 12)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 34)

- ^ Laurent (1999, p. 13)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1968, p. 18)

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1989). Mes Mémoires. Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-04862-7.

- ^ Souriau (1973, p. XI)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 67)

- ^ Hovasse (2001, p. 349)

- ^ Hovasse (2001, p. 349)

- ^ Hugo (1863, p. 81)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, p. 43)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 65)

- ^ Hugo (1863, p. 70)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 67)

- ^ a b c d e Hovasse 2001.

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 69)

- ^ Hugo (1863, p. 90)

- ^ Hugo (1863, p. 95)

- ^ Hugo (1863, p. 95)

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 355.

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 141)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 142)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 141)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 143)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, pp. 144–5)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 154)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, pp. 156–7)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 157)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1985, p. 27)

- ^ Thomasseau (2006, p. 158)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, p. 561)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, p. 535)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1992, p. 535)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 88)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 85)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 49)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, pp. 86–87)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 85)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 45)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 45)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 538)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 85)

- ^ a b Ubersfeld (1999, p. 87)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 560)

- ^ a b Hovasse 2001, p. 414.

- ^ Hugo (1985, p. 1387)

- ^ Hovasse 2001, pp. 403–5.

- ^ Hugo (1863)

- ^ Yon, Jean-Claude; Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Université de (27 November 2016). "Le cadre administratif des théâtres autour de 1830". Acta Fabula (in French). ISSN 2115-8037.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 412.

- ^ a b c Hovasse 2001, p. 412

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, pp. 104–5)

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 416.

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 109)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 95)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 115)

- ^ "Diérèse", Wikipédia (in French), 9 November 2023, retrieved 19 February 2024

- ^ Blewer (2002, p. 138)

- ^ Blewer (2002, p. 139)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 138)

- ^ a b c Hovasse 2001, p. 417.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 435.

- ^ Laurent (1999, p. 2)

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 430.

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 105)

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 422.

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 107)

- ^ a b Hovasse 2001, p. 420

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 108)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 108)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 138)

- ^ Thomasseau (1999, p. 139)

- ^ Thomasseau (1999, p. 138)

- ^ Thomasseau (1999, p. 157)

- ^ Thomasseau (1999, p. 139)

- ^ a b Hovasse 2001, p. 421.

- ^ "Histoire du Romantisme/X – La Légende du gilet rouge – Wikisource". fr.wikisource.org (in French). Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 423.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 424.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 425.

- ^ a b c Hovasse 2001, p. 428

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 426.

- ^ Gaudon, Jean (1983). "Sur « Hernani »". Cahiers de l'AIEF. 35 (1): 101–120. doi:10.3406/caief.1983.2406.

- ^ Roman, Myriam; Spiquel, Agnès. "Myriam Roman et Agnès Spiquel : Hernani, récits de bataille". Université Paris Cité.

- ^ Gaudon, Jean (1983). "Sur « Hernani »". Cahiers de l'AIEF. 35 (1): 101–120. doi:10.3406/caief.1983.2406.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, pp. 429–430.

- ^ a b c Hovasse 2001, p. 429

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 437.

- ^ Naugrette (2001, pp. 144–5)

- ^ Vielledent, Sylvie. "Hernani, ses parodies" (PDF). Université Paris Cité. pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Hovasse 2001, p. 431.

- ^ Vielledent, Sylvie. "Hernani, ses parodies" (PDF). Université Paris Cité. p. 3.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 429.

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 109)

- ^ Vielledent, Sylvie. "Hernani, ses parodies" (PDF). Université Paris Cité. p. 3.

- ^ Hovasse 2001, p. 432.

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 109)

- ^ "Éditions Stock", Wikipédia (in French), 2 December 2023, retrieved 19 February 2024

- ^ Blewer (2002, p. 106)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 114)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, pp. 140–148)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 163)

- ^ Ubersfeld (2001, p. 10)

- ^ Rosa, Guy. "Hugo et l'alexandrin de théâtre aux années 30" (PDF). Université Paris Cité. p. 10.

- ^ Thomasseau (1999, p. 158)

- ^ Blewer (2002, p. 17)

- ^ Ubersfeld (1999, p. 112)

- ^ Naugrette (2001, p. 149)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Roman, Myriam; Spiquel, Agnès. "Myriam Roman et Agnès Spiquel : Hernani, récits de bataille". Université Paris Cité.

- ^ Gautier (1877, p. 1)

- ^ Blewer (2002, pp. 383–400)

- ^ Blewer (2002, p. 19)