Funj Sultanate

Funj Sultanate السلطنة الزرقاء (in Arabic) As-Saltana az-Zarqa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1504–1821 | |||||||||

Funj branding mark (al-wasm) | |||||||||

The Funj Sultanate at its peak in around 1700 | |||||||||

| Status | Confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal emirates under Sennar's suzerainty [1] | ||||||||

| Capital | Sennar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (official language, lingua franca and language of Islam, increasingly spoken language)[2] Nubian languages (native tongue, increasingly replaced by Arabic)[3] | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam,[4] Coptic Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Islamic Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1504–1533/4 | Amara Dunqas (first) | ||||||||

• 1805–1821 | Badi VII (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council Shura[5] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Established | 1504 | ||||||||

| 14 June 1821 | |||||||||

• Annexed to Egypt Province, Ottoman Empire[a] | 13 February 1841 | ||||||||

| Currency | barter[c] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Eritrea Ethiopia | ||||||||

^ a. Muhammad Ali of Egypt was granted the non-hereditary governorship of Sudan by an 1841 Ottoman firman.[6]

^ b. Estimate for entire area covered by modern Sudan.[7] ^ c. The Funj mostly did not mint coins and the markets rarely used coinage as a form of exchange.[8] Coinage didn't become widespread in cities until the 18th century. French surgeon J. C. Poncet, who visited Sennar in 1699, mentions the use of foreign coins such as Spanish reals.[9] | |||||||||

The Funj Sultanate, also known as Funjistan, Sultanate of Sennar (after its capital Sennar) or Blue Sultanate (due to the traditional Sudanese convention of referring to black people as blue)[10] (Arabic: السلطنة الزرقاء, romanized: al-Sulṭanah al-Zarqāʼ),[11] was a monarchy in what is now Sudan, northwestern Eritrea and western Ethiopia. Founded in 1504 by the Funj people, it quickly converted to Islam, although this conversion was only nominal. Until a more orthodox form of Islam took hold in the 18th century, the state remained an "African empire with a Muslim façade".[12] It reached its peak in the late 17th century, but declined and eventually fell apart in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1821, the last sultan, greatly reduced in power, surrendered to the Ottoman Egyptian invasion without a fight.[13]

History

Origins

Christian Nubia, represented by the two medieval kingdoms of Makuria and Alodia, began to decline from the 12th century.[14] By 1365 Makuria had virtually collapsed and was reduced to a rump state restricted to Lower Nubia, until finally disappearing c. 150 years later.[15] The fate of Alodia is less clear.[14] It has been suggested that it had collapsed as early as the 12th century or shortly after, as archaeology suggests that in this period, Soba ceased to be used as its capital.[16] By the 13th century central Sudan seemed to have disintegrated into various petty states.[17] Between the 14th and 15th centuries Sudan was overrun by Bedouin tribes.[18] In the 15th century one of these Bedouins, whom Sudanese traditions refer to as Abdallah Jammah, is recorded to have created a tribal federation and to have subsequently destroyed what was left of Alodia. In the early 16th century Abdallah's federation came under attack from an invader to the south, the Funj.[19]

The ethnic affiliation of the Funj is still disputed. The first and second of the three most prominent theories suggest that they were either Nubians or Shilluk, while, according to the third theory, the Funj were not an ethnic group, but a social class.[citation needed]

In the 14th century a Muslim Funj trader named al-Hajj Faraj al-Funi was involved in the Red Sea trade.[20] According to oral traditions the Dinka, who migrated upstream the White and Blue Nile since the 13th-century disintegration of Alodia, came in conflict with the Funj, who the Dinka defeated.[21] In the late 15th/early 16th century the Shilluk arrived at the junction of the Sobat and the White Nile, where they encountered a sedentary people Shilluk traditions refer to as Apfuny, Obwongo and/or Dongo, a people now equated with the Funj. Said to be more sophisticated than the Shilluk, they were defeated in a series of brutal wars[22] and either assimilated or pushed north.[23] Anti-Funj propaganda from the later period of the kingdom referred to the Funj as "pagans from the White Nile" and "barbarians" who had originated from the "primitive southern swamps".[24]

In 1504 the Funj defeated Abdallah Jammah and founded the Funj Sultanate.[25]

Ottoman threat and revolt of Ajib

In 1523 the kingdom was visited by Jewish traveller David Reubeni, who disguised himself as a Sharif.[26] Sultan Amara Dunqas, Reubeni wrote, was continuously travelling through his kingdom. He, who "ruled over black people and white"[27] between the region south of the Nile confluence to as far north as Dongola,[26] owned large herds of various types of animals and commanded many captains on horseback.[27] Two years later, Ottoman admiral Selman Reis mentioned Amara Dunqas and his kingdom, calling it weak and easily conquerable. He also stated that Amara paid an annual tribute of 9,000 camels to the Ethiopian Empire.[28] One year later the Ottomans occupied Sawakin,[29] which beforehand was associated with Sennar.[30] It seems that to counter the Ottoman expansion in the Red Sea region, the Funj engaged in an alliance with Ethiopia. Besides camels the Funj are known to have exported horses to Ethiopia, which were then used in war against the Adal Sultanate.[31] The borders of Funj were raided by Ahmed Gurey during the war taking many slaves before stopping near the Taka mountain range near modern-day Kassala. [32][33]

Before the Ottomans gained a foothold in Ethiopia, in 1555, Özdemir Pasha was appointed Beylerbey of the (yet to be conquered) Habesh Eyalet. He attempted to march upstream along the Nile to conquer the Funj, but his troops revolted when they approached the first cataract of the Nile.[34] Until 1570, however, the Ottomans had established themselves in Qasr Ibrim in Lower Nubia, most likely a preemptive move to secure Upper Egypt from Funj aggression.[35] Fourteen years later they had pushed as far south as the third cataract of the Nile and subsequently attempted to conquer Dongola, but, in 1585, were crushed by the Funj at the battle of Hannik.[36] Afterwards, the battlefield, which was located just south of the third Nile cataract, would mark the border between the two kingdoms.[37] In the late 16th century the Funj pushed towards the Habesh Eyalet, conquering north-western Eritrea.[38] Failing to make progress against both the Funj Sultanate and Ethiopia, the Ottomans abandoned their policy of expansion.[39] Thus, from the 1590s onwards, the Ottoman threat vanished, rendering the Funj-Ethiopian alliance unnecessary, and relations between the two states were about to turn into open hostility.[40] As late as 1597, however, the relations were still described as friendly, with trade flourishing.[41]

In the meantime, the rule of sultan Dakin (1568–1585) saw the rise of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. When Dakin returned from a failed campaign in the Ethiopian–Sudanese borderlands Ajib had acquired enough power to demand and receive greater political autonomy. A few years later he forced sultan Tayyib to marry his daughter, effectively making Tayyib and his offspring and successor, Unsa, his vassals. Unsa was eventually deposed in 1603/1604 by Abd al-Qadir II, triggering Ajib to invade the Funj heartland. His armies pushed the Funj king to the south-east. Thus, Ajib effectively ruled over an empire reaching from Dongola to Ethiopia. Abd el-Qadir II, eventually deposed in December 1606, fled to Ethiopia and submitted to emperor Susenyos,[42] providing Susenyos with an opportunity to intervene in the sultanate's affairs.[43] However, the new Funj sultan, Adlan I, managed to turn the tide of war against Ajib,[44] eventually killing him in 1611 or 1612.[45] While chasing the remnants of Ajib's army to the north, Adlan II himself was deposed and succeeded by a son of the former sultan Abd al-Qadir II, Badi I. He issued a peace treaty with the sons of Ajib, agreeing to factually split the Funj state. The successors of Ajib, the Abdallab, would receive everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Nile, which they would rule as vassal kings of Sennar. Therefore, the Funj lost direct control over much of their kingdom.[46]

In 1618-1619 Bahr Negash Gebre Mariam, ruler of the Medri Bahri, helped Emperor Susneyos in a military campaign against the Sennar Sultanate. Emperor Susneyos sent Bahr Gebre to attack Mandara whose queen, Fatima, controlled a strategic caravan road from Suakin. The Bahr Negash was successful in capturing Queen Fatima, which he sent back to Emperor Susenyos' palace in Danqaz (Gorgora) and she renewed submission to the Ethiopian Empire.[47]

17th century peak

The submission of Abd al-Qadir II to the Ethiopian emperor and the possibility of a consequential invasion remained a problem for the Funj sultans. Adlan I had apparently been too weak to do something against this situation, but Badi I was able to take matters into his own hands.[49] A rich present by Susenyos, which he perhaps sent in the belief that the successors of Abd al-Qadir II would honour the submission of the latter, was rudely answered with two lame horses and first raids of Ethiopian posts.[43] Susenyos, occupied elsewhere, would not respond to that act of aggression until 1617 when he raided several Funj provinces. This mutual raiding finally escalated into a full-fledged war in 1618 and 1619, resulting in the devastation of many of the Funj eastern provinces.[50] A pitched battle was also fought, claimed by the Ethiopian sources to have been a victory, albeit this is posed doubtful by the fact that the Ethiopian troops retreated immediately afterwards. After the war, the two countries remained at peace for over a century.[51]

The Funj sultan who ruled during the war, Rabat I, was the first in a series of three monarchs under whom the sultanate entered a period of prosperity, expansion and increased contacts with the outside world, but was also confronted with several new problems.[52]

In the 17th century, the Shilluk and Sennar were forced into an uneasy alliance to combat the growing might of the Dinka. After the alliance had run its cause, in 1650, Sultan Badi II occupied the northern half of the Shilluk Kingdom.[53] Under his rule the Funj defeated the Kingdom of Taqali to the west and made its ruler his vassal.[citation needed]

Decline

Sennar was at its peak at the end of the 17th century, but during the 18th century, it began to decline as the power of the monarchy was eroded. The greatest challenge to the authority of the king were the merchant funded Ulama who insisted it was rightfully their duty to mete out justice.[citation needed]

In about 1718 the previous dynasty, the Unsab, was overthrown in a coup and replaced by Nul, who, although related to the previous Sultan, effectively founded a dynasty on his own.[54]

In 1741 and 1743 the young Ethiopian emperor Iyasu II conducted raids westwards, attempting to acquire quick military fame. In March 1744 he assembled an army of 30,000–100,000 men for a new expedition, which was initially intended as yet another raid, but soon turned into a war of conquest.[55] On the banks of the Dinder river the two states fought a pitched battle, which went in favour of Sennar.[56] Traveller James Bruce noted that Iyasu II, plundered his way back to Ethiopia, allowing him to display his campaign as a success.[57] Meanwhile, Badi IV's repulsion of the Ethiopian invasion made him a national hero.[54] Hostilities between the two states continued until the end of Iyasu II's reign in 1755, tensions caused by this war were still recorded in 1773.[58] Trade, however, soon resumed after the conflict, although on reduced scale.[59]

It has been suggested that it was Badi's victory over the Ethiopians that strengthened his power;[60] in 1743/1744 he is known to have had his vizier executed and to have taken the reins.[61] He attempted to create a new power base by purging the previous ruling clan, stripping the nobility of their land and instead empowering clients from the western and southern periphery of his realm. One of these clients was Muhammad Abu Likaylik, a Hamaj (a generic Sudannese term applied to the pre-Funj, non-Arabic or semi-Arabized people of the Gezira and Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands)[62] from east of Fazughli who was granted land immediately south of Sennar in 1747/1748.[63] He was a cavalry commander tasked to pacify Kordofan, which had become a battlefield between the Funj and the Musabb’at, refugees from the Sultanate of Darfur.[64] The Fur had the upper hand until 1755, when Abu Likayik finally managed to overrun Kordofan and turn it into his new powerbase.[65] In the meantime, Sultan Badi grew increasingly unpopular due to his repressive measures. Eventually, Abu Likayik was convinced by disaffected Funj noblemen, many of them residing in Kordofan, to march on the capital. In 1760/1761 he reached Alays at the White Nile, where a council was held in which Badi was formally deposed.[66] Afterwards, he besieged Sennar, which he entered on 27 March 1762.[67] Badi fled to Ethiopia but was murdered in 1763.[68] Thus began the Hamaj Regency, where the Funj monarchs became puppets of the Hamaj.[69]

Abu Likayik installed another member of the royal family as his puppet sultan and ruled as regent. This began a long conflict between the Funj sultans attempting to reassert their independence and authority and the Hamaj regents attempting to maintain control of the true power of the state. These internal divisions greatly weakened the state and in the late 18th century Mek Adlan II, son of Mek Taifara, took power during a turbulent time at which a Turkish presence was being established in the Funj kingdom. The Turkish ruler, Al-Tahir Agha, married Khadeeja, daughter of Mek Adlan II. This paved the way for the assimilation of the Funj into the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed]

The later 18th century saw a rapid disintegration of the Funj state. In 1785/1786 the Fur Sultanate conquered Kordofan which it managed to hold until the Egyptian invasion of 1821.[70] In the second half of the 18th century Sennar lost the Tigre in what is now Eritrea to the rising naib ("deputy") of Massawa,[71] while after 1791 Taka around the Sudanese Mareb River made itself independent.[72] The Shukriya became the new dominant power in the Butana.[citation needed] The long isolated province of Dongola finally fell to the Shaiqiya in around 1782, who installed a loyal puppet dynasty.[73][74] After 1802, the authority of the sultanate was limited to the Gezira for good.[75] In the early years of the 19th century the kingdom was plagued by excessive civil wars. Regent Muhammad Adlan, who rose to power in 1808 and whose father had been assassinated by a warlord of that period, was able to put an end to these wars and managed to stabilize the kingdom for another 13 years.[76]

In 1820, Ismail bin Muhammad Ali, the general and son of the nominally Ottoman vassal Muhammad Ali Pasha, began the conquest of Sudan. Realizing that the Turks were about to conquer his domain, Muhammad Adlan prepared to resist and ordered to muster the army at the Nile confluence, but he fell to a plot near Sennar in early 1821. One of the murderers, a man named Daf'Allah, rode back to the capital to prepare Sultan Badi VII's submission ceremony to the Turks.[77] The Turks reached the Nile confluence in May 1821. Afterwards, they travelled upstream the Blue Nile until reaching Sennar.[78] They were disappointed to learn that Sennar, once enjoying a reputation of wealth and splendour, was now reduced to a heap of ruins.[79] On 14 June they received the official submission of Badi VII.[13]

Government

Administration

The sultans of Sennar were powerful, but not absolutely so, as a council of 20 elders also had a say in state decisions. Below the king stood the chief minister, the amin, and the jundi, who supervised the market and acted as commander of the state police and intelligence service. Another high court official was the sid al-qum, a royal bodyguard and executioner. Only he was allowed to shed royal blood, as he was tasked to kill all brothers of a freshly elected king to prevent civil wars.[80]

The state was divided into several provinces governed by a manjil. Each of these province was again divided into sub-provinces governed by a makk, each of them subordinated to their respective manjil. The most important manjil was the one of the Abdallabs, followed by Alays at the White Nile, the kings of the Blue Nile region and finally the rest. The king of Sennar exercised his influence among the manjils forcing them to marry a woman from the royal clan, which acted as royal spies. A member of the royal clan also always sat at their side, observing their behaviour. Furthermore, the manjils had to travel to Sennar every year to pay tribute and account for their deeds.[81]

It was under king Badi II when Sennar became the fixed capital of the state and when written documents concerning administrative matters appeared, with the oldest known one dating to 1654.[82]

Military

The army of Sennar was feudal. Each noble house could field a military unit measured in its power by its horsemen. The population, although generally armed, was only rarely called to war, in cases of uttermost need. Most Funj warriors were slaves traditionally captured in annual slave raids called salatiya,[83] targeting the stateless non-Muslims in the Nuba mountains pejoratively referred to as Fartit.[84] The army was divided into infantry, represented by an official called muqaddam al-qawawid, and cavalry, represented by the muqaddam al-khayl.[85] The Sultan rarely led armies into battle and instead appointed a commander for the duration of the campaign, called amin jaysh al-sultan.[86] At its peak the Funj Sultanate was probably able to field about 5,000 horsemen, while in 1772 James Bruce estimated that lightly armed slave warriors fighting as infantry amounted to about 14,000 men.[87] Nomadic warriors fighting for the Funj had an own appointed leader, the aqid or qa’id.[88] Shilluk and Dinka mercenaries were also utilizied.[89]

The weaponry of the Funj warriors consisted of thrusting lances, throwing knives, javelins, hide shields and, most importantly, long broadswords which could be wielded with two hands. Body armour consisted of leather or quilts and additionally mail, while the hands were protected by leather gloves. On the heads iron or copper helmets were worn. The horses were also armoured, wearing thick quilts, copper headgear and breast plates. While armour was also manufactured locally, it was at times imported as well.[90] In the late 17th century Sultan Badi III attempted to modernize the army by importing firearms and even cannons, but they were quickly disregarded after his death not only because the import was expensive and unreliable, but also because the traditionally armed elites feared for their power.[91] James Bruce remarked that the Sultan had "not one musket in his whole army".[92] 40 years later Johann Ludwig Burckhardt noted that Mek Nimr, the now independent lord of Shendi, maintained a small force of slaves armed with muskets bought or stolen from Egyptian merchants. While they were in bad shape their mere display was enough to cause terror among Nimr's enemies.[93] In 1820 the Shaiqiya were said to have a few pistols and guns, although the overwhelming majority still used traditional weapons.[94]

Culture

Religion

Islam

By the time of the visit by David Reubeni in 1523, the Funj, originally Pagans or syncretic Christians, had converted to Islam. They probably converted to ease their rule over their Muslim subjects and to facilitate trade with neighbouring countries like Egypt.[95] Their embracement of Islam was only nominal and, in fact, the Funj effectively even delayed the Islamization of Nubia, as they temporarily strengthened African sacral traditions instead.[12] The monarchy they established was divine, similar to that of many other African states:[96] The Funj Sultan had hundreds of wives[97] and spent most of his reign within the palace, secluded from his subjects[98] and maintaining contact only with a handful of officials.[99] He was not allowed to be seen eating. On the rare occasion he appeared in public he did so only with a veil and accompanied by much pomp.[100] The Sultan was judged regularly and, if found wanting, could be executed.[101] All Funj, but especially the Sultan, were believed to be able to detect sorcery. Islamic talismans written in Sennar were believed to have special powers due to the proximity to the Sultan.[102] Among the populace even the basics of Islamic faith were not widely known.[103] Pork and beer were consumed as staple food throughout much of the kingdom,[96] the death of an important individual would be mourned by "communal dancing, self-mutilation and rolling in the ashes of the feast-fire".[104] At least in some regions, elderly, crippled and others who believed to be a burden for their relatives and friends were expected to request to be buried alive or otherwise disposed.[101] As late as the late 17th century the Funj Sultanate was still recorded to not follow the "laws of the Turks”, i. e. Islam.[105] Thus, until the 18th century Islam was not much more than a facade.[12]

Despite this, the Funj acted as sponsors of Islam from the very beginning, encouraging the settlement of Muslim holy men in their domain. In the later period civil wars forced the peasants to look to the holy men for protection; the sultans lost the peasant population to the Ulama.[citation needed]

Christianity

The collapse of the Christian Nubian states went hand in hand with the collapse of the Christian institutions.[107] The Christian faith, however, would continue to exist, although gradually declining.[a] By the sixteenth century large portions of Nubia's population would still have been Christian. Dongola, the former capital and Christian center of the Makurian kingdom,[111] was recorded to have been largely Islamized by the turn of the 16th century,[b] although a Franciscan letter confirms the existence of a community immediately south of Dongola practicing a "debased Christianity" as late as 1742.[114] According to the 1699 account of Poncet, Muslims reacted to meeting Christians in the streets of Sennar by reciting the Shahada.[115] The Fazughli region seems to have been Christian at least for one generation after its conquest in 1685; a Christian principality was mentioned in the region as late as 1773.[116] The Tigre in north-western Eritrea, who were part of the Beni Amer confederation,[117] remained Christians until the 19th century.[118] Rituals stemming from Christian traditions outlived the conversion to Islam[119] and were still practiced as late as the 20th century.[c]

From the 17th century foreign Christian groups, mostly merchants, were present in Sennar, including Copts, Ethiopians, Greeks, Armenians and Portuguese.[125] The sultanate also served as interstation for Ethiopian Christians travelling to Egypt and the Holy Land as well as European missionaries travelling to Ethiopia.[126]

Languages

In the Christian period, Nubian languages had been spoken between the region from Aswan in the north to an undetermined point south of the confluence of the Blue and White Nile.[127] They remained important during the Funj period, but were gradually superseded by Arabic.[3] This process was largely accomplished in central Sudan by the 19th century,[128] although even then there were limited reports of Nubian still being spoken as far south as the 5th cataract, if not Shendi.[129]

After the Funj conversion to Islam, Arabic grew to become the lingua franca of administration and trade while also being employed as language of religion. While the royal court would continue to speak their pre-Arabic language for some time[130] by c. 1700, the language of communication at the court had become Arabic.[131] In the 18th century, Arabic became the written language of state administration. As late as 1821, when the kingdom fell, some provincial noblemen were still not capable of speaking Arabic.[130] Evliya Çelebi (17th century) and Joseph Russegger (mid 19th century) described a pre-Arabic language in the Funj heartland.[132] Çelebi provided a listing of numerals as well as a poem, both written in Arabic script; the numerals are clearly Kanuri, while the language used for the poem remains unidentified.[133] Russegger stated that a Fungi language, sounding similar to Nubian and having absorbed many Arabic words, was spoken as far north as Khartoum, albeit already reduced to a secondary role compared to Arabic.[134] In Kordofan, Nubian was still spoken as primary or at least secondary language as late as the 1820s and 1830s.[135]

Trade

During the reign of sultan Badi III in the late 17th and early 18th century the prosperous and cosmopolitan capital of Sennar was described as "close to being the greatest trading city" in all Africa.[136] The wealth and power of the sultans had long rested on the control of the economy. All caravans were controlled by the monarch, as was the gold supply that functioned as the state's main currency. Important revenues came from customs dues levied on the caravan routers leading to Egypt and the Red Sea ports and on the pilgrimage traffic from the Western Sudan. In the late 17th century the Funj had opened up trading with the Ottoman Empire. In the late 17th century with the introduction of coinage, an unregulated market system took hold, and the sultans lost control of the market to a new merchant middle class. Foreign currencies became widely used by merchants breaking the power of the monarch to closely control the economy. The thriving trade created a wealthy class of educated and literate merchants, who read widely about Islam and became much concerned about the lack of orthodoxy in the kingdom.[137] The Sultanate also did their best to monopolize the slave trade to Egypt, most notably through the annual caravan of up to one thousand slaves. This monopoly was most successful in the seventeenth century, although it still worked to some extent in the eighteenth.[138]

Rulers

The rulers of Sennar held the title of Mek (sultan). Their regnal numbers vary from source to source.[139][140]

- Amara Dunqas 1503 – 1533/1534 (AH 940)

- Nayil 1533/1534 (AH 940) – 1550/1551 (AH 957)

- Abd al-Qadir I 1550/1551 (AH 957) – 1557/1558 (AH 965)

- Abu Sakikin 1557/1558 (AH 965) – 1568

- Dakin 1568 – 1585/1586 (AH 994)

- Dawra 1585/1586 (AH 994) – 1587/1588 (AH 996)

- Tayyib 1587/1588 (AH 996) – 1591

- Unsa I 1591 – 1603/1604 (AH 1012)

- Abd al-Qadir II 1603/1604 (AH 1012) – 1606

- Adlan I 1606 – 1611/1612 (AH 1020)

- Badi I 1611/1612 (AH 1020) – 1616/7 (AH 1025)

- Rabat I 1616/1617 (AH 1025) – 1644/1645

- Badi II 1644/1645 – 1681

- Unsa II 1681 – 1692

- Badi III 1692 – 1716

- Unsa III 1719 – 1720

- Nul 1720 – 1724

- Badi IV 1724 – 1762

- Nasir 1762 – 1769

- Isma'il 1768 – 1776

- Adlan II 1776 – 1789

- Awkal 1787 – 1788

- Tayyib II 1788 – 1790

- Badi V 1790

- Nawwar 1790 – 1791

- Badi VI 1791 – 1798

- Ranfi 1798 – 1804

- Agban 1804 – 1805

- Badi VII 1805 – 1821

Hamaj regents

- Muhammad Abu Likayik 1769 – 1775/6

- Badi walad Rajab 1775/1776 – 1780

- Rajab 1780 – 1786/1787

- Nasir 1786/1787 – 1798

- Idris wad Abu Likaylik 1798 – 1803

- Adlan wad Abu Likayik 1803

- Wad Rajab 1804 – 1806

Maps

- Map by Stefano Bonsignori (1579). The Funj ("Fuingi") are located at the top

- Map by Guillaume Delisle (1707)

- Map by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1749)

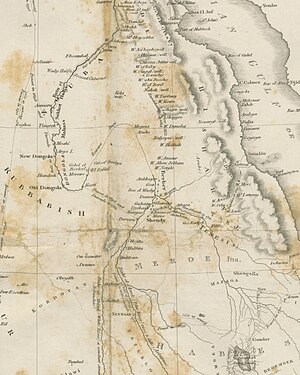

- Map by traveller James Bruce, who traversed the country in the early 1770s

- Map by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1819)

See also

Annotations

- ^ "It is astounding how long the Christian faith managed to maintain itself beyond the collapse of the Christian realms, even though gradually weakened and drained."[108] Already in 1500 a traveller who visited Nubia stated that the Nubians regarded themselves as Christians, but were so lacking in Christian instruction they had no knowledge of the faith.[109] In 1520 Nubian ambassadors reached Ethiopia and petitioned the emperor for priests. They claimed that no more priests could reach Nubia because of the wars between Muslims, leading to a decline of Christianity in their land.[110]

- ^ "The story of the Ethiopian monk Takla Alfa, who died in Dongola in 1596 (...) clearly shows that there were virtually no Christians left in Dongola."[112] Theodor Krump claims that the people of Dongola, where he was detained in February 1701, told him that just 100 years ago their ancestors were still Christians.[113]

- ^ In 1918 it has been recorded that several practices clearly of Christian origin were "common, though of course not universal, in Omdurman, the Gezira and Kordofan". These practices involved the marking of crosses on foreheads of newborns or on stomachs of sick boys as well as putting straw crosses on bowls of milk.[120] In 1927 it is written that along the White Nile, crosses were pointed on bowls filled with wheat.[121] In 1930 it was not only recorded that youths in the Gezira would be painted with crosses, but also that coins with crosses were worn in order to provide assistance against illnesses.[122] A very similar custom was known from Lower Nubia, where women wore such coins on special holidays. It seems likely that this was a living memory of the Jizya tax, which was enforced on Christians who refused to convert to Islam.[123] Customs of Christian origin were also extensively practiced in the Dongola region as well as the Nuba mountains.[124]

References

- ^ Ofcansky, Thomas (June 1991). Helen Chapin Metz (ed.). Sudan: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. The Funj. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009.

- ^ McHugh 1994, p. 9, "The spread of Arabic flowed not only from the dispersion of Arabs but from the unification of the Nile by a government, the Funj sultanate, that utilized Arabic as an official means of communication, and from the use of Arabic as a trade language."

- ^ a b James 2008, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer (1996). "Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa, till the 19th century". The Last Great Muslim Empires. History of the Muslim World, 3. Abbreviated and adapted by F. R. C. Bagley (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-55876-112-4.

The date when the Funj rulers adopted Islam is not known, but must have been fairly soon after the foundation of Sennār, because they then entered into relations with Muslim groups over a wide area.

- ^ Welch, Galbraith (1949). North African Prelude: The First Seven Thousand Years (snippet view). New York: W. Morrow. p. 463. OCLC 413248. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

The government was semirepublican; when a sultan died the great council picked a successor from among the royal children. Then—presumably to keep the peace—they killed all the rest.

- ^ "Text Viewer" فرمان سلطاني إلى محمد علي بتقليده حكم السودان بغير حق التوارث [Sultanic Firman to Muhammad Ali Appointing Him Ruler of the Sudan Without Hereditary Rights] (in Arabic). Bibliotheca Alexandrina: Memory of Modern Egypt Digital Archive. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ Avakov, Alexander V. (2010). Two Thousand Years of Economic Statistics: World Population, GDP, and PPP. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87586-750-2.

- ^ Anderson, Julie R. (2008). "A Mamluk Coin from Kulubnarti, Sudan" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (10): 68. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

Much further to the south, the Funj Sultanate based in Sennar (1504/5–1820), rarely minted coins and the markets did not normally use coinage as a form of exchange. Foreign coins themselves were commodities and frequently kept for jewellery. Units of items such as gold, grain, iron, cloth and salt had specific values and were used for trade, particularly on a local level.

- ^ Pinkerton, John (1814). "Poncet's Journey to Abyssinia". A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World. Vol. 15. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. p. 71. OCLC 1397394.

- ^ Bender, M. Lionel (1983). "Color Term Encoding in a Special Lexical Domain: Sudanese Arabic Skin Colors". Anthropological Linguistics. 25 (1): 19–27. JSTOR 30027653. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Ogot 1999, p. 91

- ^ a b c Loimeier 2013, p. 141.

- ^ a b Alan Moorehead, The Blue Nile, revised edition (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), p. 215

- ^ a b Grajetzki 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Grajetzki 2009, p. 123.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 19.

- ^ Hasan 1967, p. 176.

- ^ Loimeier 2013, pp. 140–141.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Beswick 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Beswick 2014, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Beswick 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 210.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 23.

- ^ a b Crawford 1951, p. 136.

- ^ Peacock 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Peacock 2012, p. 98.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 26.

- ^ Peacock 2012, pp. 98–101.

- ^ Burton, Richard. First Footsteps in East Africa. p. 179.

- ^ Pal Ruhela, Satya; Farah Aidid, Mohammed (1994). Somalia: From The Dawn of Civilization To The Modern Times. Vikas Pub. House. ISBN 9780706980042.

- ^ Ménage 1988, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Ménage 1988, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Peacock 2012, pp. 96–97.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 35.

- ^ Smidt 2010, p. 665.

- ^ Peacock 2012, p. 97.

- ^ Peacock 2012, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Aregay & Selassie 1971, p. 64.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 60.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 38.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 36.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 38–40.

- ^ James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, vol. 2.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 361.

- ^ Aregay & Selassie 1971, p. 65.

- ^ Aregay & Selassie 1971, pp. 65–66.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 61.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 57.

- ^ Beswick 2014, p. 115.

- ^ a b Spaulding 1985, p. 213.

- ^ Kropp 1996, pp. 116–118, note 21.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 91.

- ^ Kropp 1996, p. 125.

- ^ Aregay & Selassie 1971, p. 68.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, pp. 371–372.

- ^ McHugh 1994, p. 53.

- ^ McHugh 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Etefa 2006, pp. 17–18.

- ^ McHugh 1994, pp. 53–54.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 93.

- ^ Spaulding 1998, pp. 53–54.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 94.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 313.

- ^ Kropp 1996, p. 128.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Miran 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 383.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 101.

- ^ Beška 2020, p. 320.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 382.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 440–442.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 449–451.

- ^ McGregor 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 106.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 43–46.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Spaulding & Abu Salim 1989, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Insoll 2003, p. 123.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 70.

- ^ Paul 1954, p. 24–25.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 54.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 63.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 53–54.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Bruce 1790, p. 481.

- ^ Burckhardt 1819, p. 286.

- ^ Waddington & Hanbury 1822, p. 98.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b Spaulding 1985, p. 124.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 29.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 41.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 130.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Spaulding 1985, p. 129.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 125.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 189.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, xvii.

- ^ Zurawski 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 156.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 174.

- ^ Hasan 1967, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 150.

- ^ Zurawski 2014, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Zurawski 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 154.

- ^ Zurawski 2012, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Natsoulas 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Spaulding 1974, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 507.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 177.

- ^ Crowfoot 1918, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Chataway 1930, p. 256.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 178.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 177–184.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 68.

- ^ Aregay & Selassie 1971, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Werner 2013, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 260.

- ^ Gerhards 2023, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 33.

- ^ Loimeier 2013, p. 144.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 29.

- ^ Hammarström 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Russegger 1844, p. 769.

- ^ Spaulding 2006, pp. 395–396.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 4.

- ^ Lapidus

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul (2012). Transformations in Slavery: a History of Slavery in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

- ^ MacMichael, H. A. (1922). "Appendix I: The Chronology of the Fung Kings". A History of the Arabs in the Sudan and Some Account of the People Who Preceded Them and of the Tribes Inhabiting Dárfūr. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. OCLC 264942362.

- ^ Holt, Peter Malcolm (1999). "Genealogical Tables and King-Lists". The Sudan of the Three Niles: The Funj Chronicle 910–1288 / 1504–1871. Islamic History and Civilization, 26. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 182–186. ISBN 978-90-04-11256-8.

Bibliography

- Aregay, Merid Wolde; Selassie, Sergew Hable (1971). "Sudanese-Ethiopian Relations Before the 19th Century". In Yusuf Fadl Hasan (ed.). Sudan in Africa. Khartoum University. pp. 62–72. OCLC 248684619.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. ISBN 978-1580462310.

- Beška, Emanuel (2020). "Swan song in the Nile Valley. The Mamluk Statelet in Dongola (1812–1820)". African and Asian Studies. 29 (2): 315–329.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2014). "The Role of Slavery in the Rise and Fall of the Shilluk Kingdom". In Souad T. Ali; et al. (eds.). The Road to the Two Sudans. Cambridge Scholars. pp. 108–142. ISBN 9781443856324.

- Bruce, James (1790). Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile. Vol. IV. J. Ruthven.

- Burckhardt, John Lewis (1819). Travels in Nubia. John Murray.

- Chataway, J. D. P. (1930). "Notes on the history of the Fung" (PDF). Sudan Notes and Records. 13: 247–258.

- Connel, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. The Scarecrow. ISBN 9780810875050.

- Crawford, O. G. S. (1951). The Fung Kingdom of Sennar. John Bellows LTD. OCLC 253111091.

- Crowfoot, J. W. (1918). "The sign of the cross" (PDF). Sudan Notes and Records. 1: 55–56, 216.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36987-9.

- Etefa, Tsega Endalew (2006). Inter-ethnic Relations on a Frontier: Mätakkäl (Ethiopia), 1898-1991. Harassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05442-3.

- Gerhards, Gabriel (2023). "Präarabische Sprachen der Ja'aliyin und Ababde in der europäischen Literatur des 19. Jahrhunderts". Der Antike Sudan (in German). 34. Sudanarchäologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V: 135–152.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). "Das Ende der christlich-nubischen Reiche" (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie. X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Hammarström, Harald (2018). "A survey of African languages". The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1–57. ISBN 9783110421668.

- Hasan, Yusuf Fadl (1967). The Arabs and the Sudan. From the seventh to the early sixteenth century. Edinburgh University. OCLC 33206034.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (1975). "Chapter 1: Egypt, the Funj and Darfur". In Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland (eds.). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 4: from c. 1600 to c. 1790. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

- Insoll, Timothy (2003). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0521651714.

- James, Wendy (2008). "Sudan: Majorities, Minorities, and Language Interactions". In Andrew Simpson (ed.). Language and National Identity in Africa. Oxford University. pp. 61–78. ISBN 978-0199286744.

- Kropp, Manfred (1996). "Äthiopisch–sudanesische Kriege im 18. Jhdt.". Der Sudan in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (in German). Peter Lang. pp. 111–131. ISBN 3631480911.

- Loimeier, Roman (2013). Muslim Societies in Africa: A Historical Anthropology. Indiana University.

- McGregor, Andrew James (2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Praeger. ISBN 0275986012.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. Northwestern University. ISBN 0810110695.

- Ménage, V. L. (1988). "The Ottomans and Nubia in the Sixteenth Century". Annales Islamoloiques. 24. Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire: 137–153.

- Miran, Jonathan (2010). "Constructing and deconstructing the Tigre frontier space in the long nineteenth century". In Gianfrancesco Lusini (ed.). History and Language of the Tigre-Speaking Peoples. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Naples, February 7-8, 2008. Università di Napoli. pp. 33–50. ISBN 9788895044682.

- Nassr, Ahmed Hamid (2016). "Sennar Capital of Islamic Culture 2017 Project. Preliminary results of archaeological surveys in Sennar East and Sabaloka East (Archaeology Department of Al-Neelain University concessions)". Sudan & Nubia. 20. The Sudan Archaeological Research Society: 146–152.

- Natsoulas, Theodore (2003). "Charles Poncet's Travels to Ethiopia, 1698 to 1703". In Glenn Joseph Ames; Ronald S. Love (eds.). Distant Lands and Diverse Cultures: The French Experience in Asia, 1600–1700. Praeger. pp. 71–96. ISBN 0313308640.

- O'Fahey, R.S.; Spaulding, J.L (1974). Kingdoms of the Sudan. Studies of African History Vol. 9. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-77450-4.

- Ogot, B. A., ed. (1999). "Chapter 7: The Sudan, 1500–1800". General History of Africa. Vol. V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 89–103. ISBN 978-0-520-06700-4.

- Oliver, Roland; Atmore, Anthony (2001). Medieval Africa, 1250-1800. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-79024-6.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea. ISBN 0932415199.

- Paul, A. (1954). "Some aspects of the Fung Sultanate". Sudan Notes and Records. 35, 2: 17–31.

- Peacock, A.C.S. (2012). "The Ottomans and the Funj sultanate in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 75 (1). University of London: 87–111. doi:10.1017/S0041977X11000838.

- Russegger, Joseph (1844). Reise in Egypten, Nubien und Ost-Sudan. Vol. 2, Part 2. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagshandlung.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2010). "Sinnar". In Siegbert Uhlig, Alessandro Bausi (ed.). Encyclopedia Aethiopica. Vol. 4. Harrassowitz. pp. 665–667. ISBN 9783447062466.

- Spaulding, Jay (1972). "The Funj: A Reconsideration". The Journal of African History. 13 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000256. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 161129633.

- Spaulding, Jay (1974). "The Fate of Alodia" (PDF). Meroitic Newsletter. 15: 12–30. ISSN 1266-1635.

- Spaulding, Jay (1985). The Heroic Age in Sennar. Red Sea. ISBN 978-1569022603.

- Spaulding, Jay (1998). "Early Kordofan". In Endre Stiansen and Michael Kevane (ed.). Kordofan Invaded: Peripheral Incorporation in Islamic Africa. Brill. pp. 46–59. ISBN 978-9004110496.

- Spaulding, Jay (2006). "Pastoralism, Slavery, Commerce, Culture and the Fate of the Nubians of Northern and Central Kordofan Under Dar Fur Rule, ca. 1750-ca. 1850". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 39 (3). Boston University African Studies Center. ISSN 0361-7882.

- Spaulding, Jay; Abu Salim, Muhammad Ibrahim (1989). Public Documents from Sinnar. Michigan State University. ISBN 0870132806.

- Waddington, George; Hanbury, Barnard (1822). Journal of a Visit to some Parts of Ethiopia. William Clowes.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche ["Christianity in Nubia. History and shape of an African church"] (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12196-7.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2012). Banganarti on the Nile. An archaeological guide (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.

Further reading

- Robinson, Arthur E. "Some Notes on the Regalia of the Fung Sultans of Sennar", Journal of the Royal African Society, 30 (1931), pp. 361–376

- Lobban, Richard A. (1983). "A Genealogical and Historical Study of the Mahas of the "Three Towns," Sudan". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 16 (2): 231–262. doi:10.2307/217787. JSTOR 217787.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1975). "Ethiopia's economic and cultural ties with the Sudan from the middle ages to the mid-nineteenth century". Sudan Notes and Records. 56. University of Khartoum: 53–94. ISSN 0375-2984.

- Spaulding, Jay (2018). "The Art of the Memory and Chancery in Sinnar". In William H. Worger; Charles Ambler; Nwando Achebe (eds.). A Companion to African History. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 421–430. ISBN 978-1-119-06350-6.