Battle of Front Royal

| Battle of Front Royal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Union Army under Banks entering the town, by Edwin Forbes | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Reese Kenly | Thomas J, "Stonewall" Jackson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,063[1] | 3,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 773 | 36 | ||||||

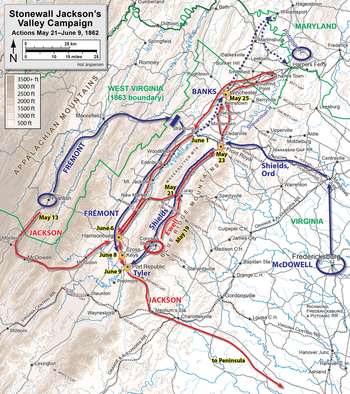

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought on May 23, 1862, during the American Civil War, as part of Jackson's Valley campaign. Confederate forces commanded by Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson were trying to keep Union forces engaged in the Shenandoah Valley to prevent them from joining the Peninsula campaign. After defeating Major General John C. Frémont's force in the Battle of McDowell, Jackson turned against the forces of Major General Nathaniel Banks.

Banks had most of his force at Strasburg, Virginia, with smaller detachments at Winchester and Front Royal. Jackson attacked the position at Front Royal on May 23, surprising the Union defenders, who were led by Colonel John Reese Kenly. Kenly's men made a stand on Richardson's Hill and used artillery fire to hold off the Confederates, before their line of escape over the South Fork and North Fork of the Shenandoah River was threatened. The Union troops then withdrew across both forks to Guard Hill, where they made a stand until Confederate troops were able to get across the North Fork. Kenly made one last stand at Cedarville, but an attack by 250 Confederate cavalrymen shattered the Union position. Many of the Union soldiers were captured, but Banks was able to withdraw his main force to Winchester. Two days later, Jackson then drove Banks out of Winchester, and won two further victories in June. Jackson's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley had tied down 60,000 Union troops from joining the Peninsula campaign, and his men were able to join Robert E. Lee's Confederate force in time for the Seven Days battles.

Background

In March 1862, during the American Civil War, Union forces led by Major General George B. McClellan began the Peninsula campaign on the Virginia Peninsula. To the west, in the Shenandoah Valley, Union Major General Nathaniel Banks pushed the Confederate troops of Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson to the south. Jackson had orders to try to distract Union troops in the Valley so that they would not be available for McClellan. By March 21, Union high command decided that much of Banks's force was not necessary for the security of the Shenandoah Valley,[2] and much of it was sent to Washington, D.C., leaving only about 9,000 of Banks's 35,000 men left in the Valley. On March 23, Jackson attacked the Union forces in the Valley in the First Battle of Kernstown. The Confederate attack was repulsed,[1] but it still was considered concerning enough to return the rest of Banks's command to the Valley and to hold another corps at Manassas, Virginia, depriving McClellan's campaign of about 60,000 men.[3]

After Kernstown, Jackson withdrew south in the valley, where he joined forces with Major General Richard Ewell. Leaving Ewell and his men to face Banks,[1] Jackson took his troops southwest towards McDowell, Virginia, in early May to confront a Union force commanded by Major General John C. Frémont. Part of Frémont's command led by Brigadier General Robert H. Milroy attacked Jackson's men on May 8 in the Battle of McDowell. The Confederates were victorious, and Frémont withdrew his force.[4] Jackson then moved his men back north to face Banks. By then, part of Banks's force had again been transferred out of the Valley,[1] and on May 12, the division of Brigadier General James Shields was ordered east. Banks then withdrew his remaining force to Strasburg.[5]

Jackson's approach

Meanwhile, Ewell had received an order on May 17 dated May 13 from General Joseph E. Johnston to take his force from the Valley to support Johnston's army against McClellan. Jackson sent a message to Johnston that same day requesting that Ewell be allowed to remain with his command so that a blow could be struck against Banks, and on May 18 Jackson and Ewell decided that Ewell should remain under Jackson's authority until the reply from Johnston was received. As it took several days for communications to travel between Jackson and Johnston, Jackson did not receive a reply on May 20, when another set of orders for Ewell to move east were received. Jackson then contacted General Robert E. Lee, an advisor to Confederate President Jefferson Davis requesting the continued use of Ewell's men, but another message from Johnston arrived later that day giving Jackson discretionary use of Ewell's command.[6]

Between Jackson and Ewell's forces, the Confederates nominally had 17,000 men,[1] although historian Gary Ecelbarger estimates that due to desertion and straggling the true number of effective was closer to 12,000 or 14,000.[7] The Confederates resumed moving north to strike Banks.[1] The Union forces at Strasburg had built fortifications facing south, but Jackson decided to move to the east and destroy the Union outpost at Front Royal. By taking Front Royal, Jackson could sever Banks's communications to the east and then get into the rear of the Strasburg position, either capturing it or forcing its abandonment. The Confederates began their march on May 21,[8] crossing Massanutten Mountain and entering the Page Valley to approach Front Royal.[1] At the time of the Confederate approach, Banks had about 6,500 men in Strasburg,[9] about 1,000 in Front Royal,[10][11] and 1,000 in Winchester.[9] Jackson did not know the exact Union strengths, but was aware that the force at Front Royal was weaker than that at Strasburg.[12] Front Royal and Strasburg were separated by about 12 miles (19 km) on the more direct railroad route, although longer paths existed on roads.[13]

Battle

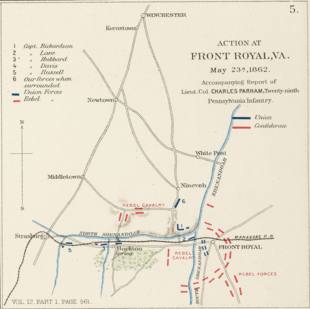

Initial Confederate attack

Jackson prepared his attack on the morning of May 23. Colonel[a] Turner Ashby's cavalry was sent between Front Royal and Strasburg to cut telegraph lines and the railroad to prevent Union forces from moving between the two towns. Unaware that he greatly outnumbered the Union force in Front Royal, Jackson decided against attacking from the direct route, the Luray Road. Instead, Ewell's men were to take the Gooney Manor Road in a flanking attack. The Stonewall Brigade and some artillery were to remain at Asbury's Chapel, which was 4.5 miles (7.2 km) from Front Royal. Any Union forces withdrawing from Front Royal would have to cross both the South Fork and the North Fork of the Shenandoah River.[16] Ecelbarger suggests that the decision to concentrate on a single road would also prevent Union escapees from Front Royal from providing Banks with an accurate estimate of the size of Jackson's command.[17]

The Confederates learned from captured pickets that the Union force in Front Royal was the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment, so Jackson ordered the Confederate 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment to the front of the Confederate column. The Confederate Maryland regiment had recently had an incident with mutiny, but Colonel Bradley T. Johnson made a patriotic speech that energized the unit. At about 2:00 pm, the Confederate attack began, with the Marylanders in front and Major Roberdeau Wheat's notoriously unruly battalion of Louisiana Tigers behind, with the rest of Brigadier General Richard Taylor's Louisiana brigade in reserve.[18] The Maryland regiment and Wheat's men totaled about 450 men.[19] Belle Boyd rode from the town to give Jackson information about the Union force, although historian James I. Robertson Jr. notes that Boyd's significance at Front Royal has been greatly exaggerated[20] and historian Peter Cozzens states that Boyd "told [Jackson] little or nothing about the Yankee force that he did not already know".[21]

The Union troops were caught by surprise, unaware that the Confederates had infantry in the area.[22] Banks had not stationed any cavalry at Front Royal, and the lack of cavalry in the morning prevented Union forces from learning of the Confederate advance earlier.[23] The Confederate attack quickly drove the Union forces from Front Royal and their camp, and the Union commander, Colonel John Reese Kenly, withdrew what remained of his force onto Richardson's Hill,[24] a height between Front Royal and the South Fork,[25] and deployed two 10-pounder Parrott rifles.[26] Some of Kenly's men were captured within the town,[24] and a Union supply train was captured as well.[27] Not much organized resistance was met within the town; one Confederate soldier referred to the town stage of the battle as "more like a police riot than a fight between soldiers".[28] In front of the new Union position was an open meadow, which would have to be crossed to frontally attack Kenly's position.[29] Kenly had about 700 infantrymen remaining in line at this point.[30] The two Parrott guns fired effectively on the Confederates.[22]

Union withdrawal to Richardson's and Guard Hills

With the two Union cannon battering his lines, Jackson had his chief of artillery, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, bring up artillery to counter the Union fire, but the first battery that reported was armed only with guns of too short of range to reach the Union position. Crutchfield was eventually able to locate three cannons with long enough ranges,[24] and a fifteen-minute artillery duel followed. Kenly tried to make his line seem stronger than it was. A small detachment of the 29th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment guarded the area between the two forks of the river,[31] and 100 men from two companies of the 5th New York Cavalry Regiment, which Banks had sent from Strasburg that morning despite being unaware of the battle,[32] arrived and sortied against the skirmishers of the Confederate 1st Maryland.[31] Meanwhile, Johnson's Marylanders attacked from the center, the 6th Louisiana Infantry Regiment attacked the Union left, and more of Taylor's men fought with the Union right. Some of the Confederate cavalry to the west,[24] the 2nd Virginia Cavalry Regiment and the 6th Virginia Cavalry Regiment under Colonel Thomas Flournoy, also raced for the bridge over the North Fork, as Confederate control of that bridge would cut off the last Union line of retreat.[24] These cavalrymen had cut railroad and telegraph lines earlier in the day before heading for the fighting at Front Royal.[33]

The arrival of Flournoy's cavalry convinced Kenly to withdraw at around 4:30 pm. The Union troops withdrew across the bridges over the South Fork and the North Fork, and lit the bridges on fire,[34] and burned some of their supplies to prevent them from falling into Confederate hands.[35] The Confederates were able to put out the fires on the South Fork bridge, and Jackson sent aides to bring up the artillery and Stonewall Brigade left at Asbury's Chapel. While the commander of the Stonewall Brigade, Brigadier General Charles Sidney Winder, had put his men and the artillery in march behind the rest of the Confederate troops, they were still too far to the rear to be available for the fighting at Front Royal.[36] Kenly reformed his command on Guard Hill across the North Fork, while many of the Confederates became disorganized and plundered the abandoned Union camp.[37] With the addition of about 100 men from the detachment of the 29th Pennsylvania, Kenly defended Guard Hill with about 800 men.[38] News did not reach Banks of the fighting at Front Royal until about 5:45 pm, when a single messenger reached his headquarters.[39]

Flournoy's pursuit

At around 6:00 pm, a few of Flournoy's men were able to cross at a ford, and part of the 8th Louisiana Infantry Regiment was able to swim across. They were able douse the fire on the North Fork bridge.[40] While a portion of the bridge collapsed, enough of the span remained that men could cross single file.[41] With the Guard Hill position untenable with Confederates across the river, Kenly withdrew his men to the hamlet of Cedarville, Virginia.[40] Jackson ordered Flournoy to push 250 cavalrymen across the charred bridge and pursue the Union troops; Jackson himself followed behind Flournoy's men.[42] Making a stand about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of Cedarville,[43] Kenly deployed his artillery, and ordered the New York cavalrymen to charge. Instead, the cavalry's commander lost his nerve and ordered his men to flee the field. The remaining Union troops formed a line at Fairview, the house of local man Thomas McKay.[44] Flournoy's men charged the position twice,[10] undeterred by a volley from the Union troops[45] that cut apart Company B of the 6th Virginia.[46] The Union line broke into confusion in the melee.[10] Kenly suffered multiple wounds during the melee and was captured, as were most of the Union troops.[47]

While Jackson had fought at Front Royal, Ashby had encountered Union troops during his mission. At about 2:00 pm, his men attacked Buckton Station on the Manassas Gap Railroad.[48] The position was defended by elements of the 3rd Wisconsin Infantry Regiment and the 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment,[49] a force of about 150 men.[50] An attack made by 300 Confederates was repulsed with the loss of two promising officers, and a second charge fared little better. Withdrawing down the railroad, Ashby had the railroad line and the telegraph wires cut, accomplishing his purpose of isolating Front Royal from Banks. Cozzens describes the needless fighting at Buckton Station as "a waste of lives".[51]

Aftermath

Cozzens places Jackson's losses (excluding Ashby's action) at 36 men killed and wounded, while stating that Kenly's force suffered 773 casualties, of which 691 were as prisoners.[52] Robertson estimates the Union prisoners at 700, and places Jackson's losses at less than 100.[10] The National Park Service gives Union losses as 904 and Confederate losses at 56.[1] Historian Robert G. Tanner says the Union lost about 900 men, and the Confederates a little over 100.[53] Ecelbarger estimates Union losses at about 900.[54] The Confederates also captured both Parrott rifles, a number of wagons, and about $300,000 worth of supplies. Ashby's expedition netted the capture of two locomotives.[10] A Union soldier, William Taylor, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1897 for his actions in the bridge-burning at Front Royal and in the later Battle of Weldon Railroad.[55] To prevent being cut off from Winchester,[56] Banks responded to the fall of Front Royal by rapidly withdrawing from Strasburg. Jackson attacked part of the withdrawing force at Middletown the next day, and then defeated Banks in the First Battle of Winchester on May 25.[1]

After defeating Banks at Winchester, Jackson advanced his force towards Harpers Ferry. Meanwhile, Frémont and Shields moved their forces towards Strasburg to concentrate against Jackson. Ashby was killed during a skirmish on June 6. Ewell was tasked with fighting Frémont, and defeated his force at the Battle of Cross Keys on June 8. While leaving the field at Cross Keys to rejoin Jackson, Ewell's men burned a bridge to prevent Frémont from joining forces with Shields.[57] On June 9, Jackson defeated Shields in the Battle of Port Republic. With Shields and Frémont withdrawing, Jackson was able to take his force from the Shenandoah Valley and join Lee's army for the Seven Days battles. Jackson's Valley Campaign had successfully prevented Union forces from joining McClellan.[1]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Stonewall Jackson's 1862 Campaign in the Valley". National Park Service. July 1, 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Lewis 1998, pp. 74, 76.

- ^ Lewis 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Tanner 1998, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 278.

- ^ Robertson 1997, pp. 386–389.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Robertson 1997, pp. 390–392.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson 1997, p. 398.

- ^ Tanner 1976, p. 206.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Warner 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 425.

- ^ Robertson 1997, p. 393.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 295–298.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Robertson 1997, p. 395.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 300.

- ^ a b Gwynne 2014, p. 280.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e Robertson 1997, p. 396.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Tanner 1976, p. 213.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 299.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 57.

- ^ a b Cozzens 2008, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 62.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 74.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 302.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Robertson 1997, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 302–303.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, pp. 76, 78.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 81.

- ^ a b Cozzens 2008, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Tanner 1976, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Robertson 1997, p. 397.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 304–305.

- ^ Gwynne 2014, p. 281.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 305, 307.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 296.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 68.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, pp. 307–309.

- ^ Cozzens 2008, p. 307.

- ^ Tanner 1976, p. 215.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, p. 88.

- ^ "William Taylor". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Ecelbarger 2008, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Pfanz 1998, pp. 82–84.

Sources

- Cozzens, Peter (2008). Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Ecelbarger, Gary L. (2008). Three Days in the Shenandoah: Stonewall Jackson at Front Royal and Winchester. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806138862.

- Gwynne, S. C. (2014). Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4516-7328-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Lewis, Thomas A. (1998). "First Kernstown, Virginia". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Pfanz, Donald C. (1998). "Cross Keys, Virginia". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 82–84. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Robertson, James I. (1997). Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-864685-1.

- Tanner, Robert G. (1976). Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign Spring 1862. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- Tanner, Robert G. (1998). "McDowell, Virginia". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Warner, Ezra J. (2006) [1959]. Generals in Gray (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3150-3.

Further reading

- Clark, Champ (1984). Decoying the Yankees: Jackson's Valley Campaign. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-4724-X.

- Martin, David G. (1994). Jackson's Valley Campaign: November 1861 – June 1862 (Revised ed.). Philadelphia: Combined Books. ISBN 0-938289-40-3.

External links

Media related to Battle of Front Royal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Front Royal at Wikimedia Commons