Battle of Colonia del Sacramento (1826)

| Battle of Colonia del Sacramento | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cisplatine War | |||||||

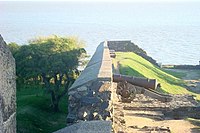

The old walls of Colonia del Sacramento | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Besieged forces:[3] Unknown, at least 24 |

Besieging troops:[5][6] +110 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

84:[9][10] 32 killed 52 wounded 1 brig sunk |

1 brig sunk 3 gunboats captured | ||||||

Location within Uruguay | |||||||

The battle of Colonia del Sacramento (or Colônia do Sacramento) consisted of a series of failed attempts made by admiral William Brown of capturing the town of Colonia del Sacramento, which was under Brazilian control and being sieged on land by insurgent Uruguayan forces, in the context of the Cisplatine War between the Empire of Brazil and the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. The confrontations began in the morning of 26 February 1826 and ended on 14 March 1826.

Background

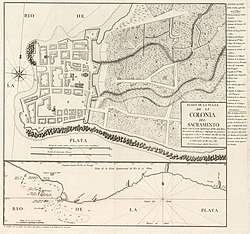

The walled town of Colonia del Sacramento was a strategic point for the Brazilians due to its proximity to the city of Buenos Aires, capital of the United Provinces, which was suffering a naval blockade by the Imperial Brazilian Navy. The Brazilians used its port as a hub for resupplying ships in the Río de la Plata and thus continue on blockading the port of Buenos Aires. For this reason, the town was defended by a local garrison in the fort and batteries, and 4 small vessels: the brig Real Pedro, the brigantine Pará and the schooners Liberdade do Sul and Conceição.[4]

On 22 February 1826, days after the battle of Punta Colares, admiral William Brown was informed by captain José Murature, who had just returned from Montevideo in the cutter Luisa, that the Brazilian fleet was anchored parallel to Punta del Indio and that the Brazilian corvette Itaparica was undergoing repairs for the damage it had suffered in the action of Punta Colares. Brown then decided to launch a surprise attack on the Brazilian fleet, setting sail at noon that day.[12] Brown's naval squadron consisted of the frigate 25 de Mayo, the barque Congreso, the brigs Republica, Belgrano and Balcarce and the schooner Sarandí.[13]

The initial plan was to attack the Brazilian fleet at night, but due to an error, the Argentines lost the surprise and the Brazilians, perceiving the enemy approach, quickly sailed away. Brown decided not to chase them and instead went north for a combined attack on Colonia del Sacramento, which was being sieged on land by a 400 men detachment of Juan Antonio Lavalleja's army, commanded by Ramón Cáceres.[5][14]

- The gate and bastions of São Miguel (or San Miguel) and São Pedro (or San Pedro) in Colonia del Sacramento

Previous actions

Brown reached Colonia del Sacramento on the evening of 25 February 1826, anchoring his ships out of the reach of the town's fortress cannons, and sent an envoy with a request calling on for the Brazilian commander, brigadier Manuel Jorge Rodrigues, a veteran of the Peninsular War, to surrender.[5][14]

The request read:[14]

"On board the frigate 25 de Mayo, 25 February 1826.

The General in Chief of the squadron of the Argentine Republic, on behalf of his Government, orders the Governor of Colonia del Sacramento to surrender it with the maritime forces stationed in its port, within a peremptory period of 24 hours, warning its Governor, that in the affirmative case, all existing properties in the town will be respected, and neither the population nor the boats will be set on fire.

The undersigned expects that the Governor, out of humanity, and in order to avoid any bloodshed, will accede to this request, based on the superiority of its forces in the Río de la Plata.

For no other reason, greets the Governor with all consideration.

William Brown.

Your excellency Mr. Governor of Colonia del Sacramento".

| Commanders |

|---|

|

To which Rodrigues replied:[15]

"Colonia del Sacramento, 25 February 1826.

The Brigadier of the National and Imperial armies and Governor of this town, responds on his behalf and on behalf of the entire garrison that he has the honor to reply to the request of the General in Chief of the Squadron of the Argentine Republic, that only the fate of the weapons decides the fate of the towns.

Greetings to Mr. General in Chief with all consideration.

Manuel Jorge Rodrigues.

Your excellency Mr. General in Chief of the Squadron of the Argentine Republic".

Frigate captain Frederico Mariath, the commander of the Brazilian ships in Colonia del Sacramento, had convened a council to decide how the defence of the town should be carried out. Mariath suggested that his four ships be anchored under the protection of the bastions of Carmen and Santa Rita, with their sides facing the port, as to provide fire support. This proposal was accepted by Jorge Rodrigues. Eight of the ships' cannons were disembarked to form two batteries on land: one was placed at the Tambor bastion, in order to protect the ships and to prevent the Argentines from disembarking on the town's mole, and the other was placed between the bastions of São Pedro and São Miguel.[16] Four hours after having sent his envoy and upon receiving the answer, admiral Brown ordered his men to begin the attack on Colonia del Sacramento.[15]

Battle

Initial attack

At dawn on 26 February the Brazilians were already in position for the upcoming attack: Frederico Mariath was with Manuel Jorge Rodrigues in Tambor; the batteries of Santa Rita and São Pedro were commanded by lieutenants Antônio Leocádio do Couto and José Inácio de Santa Rita, respectively; the then young lieutenant Joaquim José Inácio was aboard one of the Brazilian ships.[5]

The Argentine squadron began the approach from the southeast,[a] exchanging heavy fire with the São Pedro bastion on land for more than two hours, during which the brig Belgrano broke away from its formation after crossing the islet of San Gabriel, running aground on the islet's east bank, dangerously close to the enemy batteries, which focused their fire on it.[5][17] Despite the efforts to lift the Belgrano and the other vessels sent on its rescue, the ship was abandoned by its crew after a shot from Santa Rita killed its captain and put 17 of its men out of combat.[b][5] At night admiral Brown signaled to stop the hostilities in order to gain some time and to send another envoy carrying a message to Jorge Rodrigues, in which Brown declared:[18]

"I believe that the time has come to fulfill the offer that I made yesterday to you the Governor. As such, I hope that you decide immediately on such a just intimation, because otherwise, you will suffer all the rigor that your tenacity deserves, whom may God protects for many years".

W. Brown.

26 February 1826.

Manuel Jorge Rodrigues replied:[19][20][21]

"Tell the General in Chief, that what has been said has been said".

The hostilities resumed and continued on for the rest of the night. Admiral Brown, convinced his larger ships were inappropriate to invest against Colonia del Sacramento for fear they could run aground, decided to leave, sailing away from the Brazilian batteries and anchoring his ships between the Hornos islands in order to wait for the arrival of the reinforcement of 6 gunboats, which were small enough to carry out a landing on Colonia del Sacramento.[19][20]

That night, Mariath ordered the schooner Conceição to leave the port in order to set the Belgrano on fire, as he feared the high tide could make it float again. The schooner did not succeed in setting the Belgrano on fire, being chased by the Argentines, but still managed to escape and sail to Montevideo where it delivered news of the Argentine attack on Colonia del Sacramento to admiral Rodrigo Ferreira Lobo, commander of the Brazilian naval forces in the Río de la Plata.[19]

| Order of battle[5][22] | ||

|---|---|---|

| United Provinces | Empire of Brazil | |

|

| |

Second attack

On the night of 1 March 1826, admiral Brown once again attacked Colonia del Sacramento, this time in a coordinated effort with Juan Antonio Lavalleja.[19] The Argentines hoped the attack on land by the besieging forces would divide the Brazilians and make Brown's landing easier.[23] A few days earlier, on 27 February 1826, Brown's fleet had been reinforced by the 6 gunboats he had requested and also a hospital ship: Pepa. Each gunboat had a crew of 30 men and was armed with a single cannon.[24] Brown's goal was to set all the Brazilian ships on fire, with the exception of the Real Pedro, which he planned to capture in order to replace the Belgrano. From 28 February to 1 March, 200 of Brown's men were selected and armed to disembark on Colonia del Sacramento. The men were divided into groups and given incendiary bottles and grog.[25]

At 22:30 the 6 gunboats, together with two auxiliary boats, silently sailed towards the town. They were divided into two groups, departing from the sides of the frigate 25 de Mayo: one group from the right and one from the left, commanded by Tomás Espora and Leonardo Rosales respectively. At 23:45, however, the Brazilians noticed the Argentine approach towards the mole and opened fire from the batteries. The crew of the Brazilian ships, upon hearing the shots, also opened fire against the Argentines.[26]

Espora and Rosales attacked them, but the remaining 4 gunboats were dragged close to the town's fort by the wind and the current, coming under fire by the bastions of Carmen and Tambor and also the Brazilians entrenched on the mole and its surroundings, which resulted in many casualties. The Argentines managed to board the brig Real Pedro and set it on fire, lighting up the night scene with a glare, but had to help the gunboats that ran aground near the mole, being subject to intense enemy fire. Jorge Rodrigues, knowing the control of the mole was crucial, personally marched on it commanding the Brazilians.[27]

The attack on land by the besieging forces commanded by Ramón Cáceres did not happen. Cáceres was ready and in position to attack the town, but received orders from Lavalleja at 21:00 not to attack it. Cáceres imagined Lavalleja had warned Brown about this order.[23]

Before dawn, the Argentines gave up the attack and withdrew, abandoning the gunboats 4, 6 and 7, which were captured by the Brazilians. The Argentines suffered dozens of casualties, with some 40 soldiers and officers killed and 80 wounded.[28] The attack cost the Brazilians 19 dead and 10 wounded and the loss of the Real Pedro, which was burned and destroyed.[7]

Final actions

After the attack on 1 March, in order to save ammunition and hoping for the aid of Lavalleja's troops, Brown ordered his ships only to fire 6 shots each during daytime and to practice assaults on the port at night, as to keep the Brazilians in a constant state of alert.[29] Lavalleja finally arrived on 11 March and presented himself aboard Brown's flagship, excusing himself for his previous lack of initiative and telling Brown he could count on his help with 1,700 men and 12 cannons to attack Colonia del Sacramento. However, concerned with Lavalleja's indecisiveness, Brown told him he had received orders on 8 March to abandon the attack.[30]

Aftermath

Admiral Rodrigo Ferreira Lobo was replaced by Rodrigo Pinto Guedes, who reached Montevideo on 12 March, but only assumed command of the Brazilian fleet in the Río de la Plata on 12 May. Ferreira Lobo had earned the distrust and anger of both the Brazilian sailors in the theater of operations and the court in Rio de Janeiro due to his excessive passiveness and lack of initiative in dealing with the Argentines.[9]

On 14 March,[c] two days, therefore, after Pinto Guedes arrived in Montevideo, admiral Brown, fearing that the new Brazilian admiral would be more aggressive than his predecessor, decided to abandon the attack on Colonia del Sacramento, sailing back to Buenos Aires that same day.[9] A Brazilian squadron consisting of 18 ships was stationed near the San Gabriel islet waiting for Brown in order to attack him, but he managed to sail past it, safely reaching Buenos Aires.[11]

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Serviço de Doumentação da Marinha 2006, p. 91.

- ^ a b Carranza 1916, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carneiro 1946, p. 184.

- ^ Carranza 1916, p. 68.

- ^ a b Donato 1987, p. 269.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 55–56, 61, 68.

- ^ a b c d Carneiro 1946, p. 186.

- ^ Garcia 2012, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Carranza 1916, p. 70.

- ^ Carranza 1916, p. 55.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c Carranza 1916, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Carranza 1916, p. 58.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Carranza 1916, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Carneiro 1946, p. 185.

- ^ a b Carranza 1916, p. 60.

- ^ Barroso 2019, p. 136.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 55–57, 61–62, 68.

- ^ a b Carranza 1916, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Carranza 1916, p. 60-61.

- ^ Carranza 1916, p. 61.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Carranza 1916, p. 69.

- ^ Carranza 1916, pp. 69–70.

Bibliography

- Barroso, Gustavo (2019). História Militar do Brasil (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brasilia: Senado Federal. ISBN 978-85-7018-495-5.

- Carneiro, David (1946). História da Guerra Cisplatina (PDF) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

- Carranza, Angel Justiniano (1916). Campañas navales de la Republica Argentina: Tomo IV (in Spanish). Buenos Aires.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Donato, Hernâni (1987). Dicionário das Batalhas Brasileiras (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Editora Ibrasa.

- Garcia, Rodolfo (2012). Obras do Barão do Rio Branco VI: efemérides brasileiras (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brasília: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão. ISBN 978-85-7631-357-1.

- Serviço de Doumentação da Marinha (2006). Introdução à História Marítima Brasileira (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Serviço de Doumentação da Marinha. ISBN 85-7047-076-2.