Balts

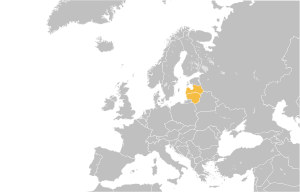

Countries with a predominantly Baltic population | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6.5–7.0 million (including the diaspora)[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,397,418[3] | |

| 1,175,902[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Baltic languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism and Protestantism; minority Eastern Orthodoxy and Baltic neopaganism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Slavs | |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Balts or Baltic peoples (Lithuanian: baltai, Latvian: balti) are a group of peoples inhabiting the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea who speak Baltic languages. Among the Baltic peoples are modern-day Lithuanians (including Samogitians) and Latvians (including Latgalians) — all East Balts — as well as the Old Prussians, Curonians, Sudovians, Skalvians, Yotvingians and Galindians — the West Balts — whose languages and cultures are now extinct.

The Balts are descended from a group of Proto-Indo-European tribes who settled the area between the lower Vistula and southeast shore of the Baltic Sea and upper Daugava and Dnieper rivers, and which over time became differentiated into West and East Balts. In the fifth century CE, parts of the eastern Baltic coast began to be settled by the ancestors of the Western Balts, whereas the East Balts lived in modern-day Belarus, Ukraine and Russia. In the first millennium CE, large migrations of the Balts occurred. By the 13th and 14th centuries, the East Balts shrank to the general area that the present-day Balts and Belarusians inhabit.

Baltic languages belong to the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. One of the features of Baltic languages is the number of conservative or archaic features retained.[5][better source needed]

Etymology

Medieval German chronicler Adam of Bremen in the latter part of the 11th century AD was the first writer to use the term "Baltic" in reference to the sea of that name.[6][7] Before him various ancient places names, such as Balcia,[8] were used in reference to a supposed island in the Baltic Sea.[6]

Adam, a speaker of German, connected Balt- with belt, a word with which he was familiar.

In Germanic languages there was some form of the toponym East Sea until after about the year 1600, when maps in English began to label it as the Baltic Sea. By 1840, German nobles of the Governorate of Livonia adopted the term "Balts" to distinguish themselves from Germans of Germany. They spoke an exclusive dialect, Baltic German, which was regarded by many as the language of the Balts until 1919.[9][10]

In 1845, Georg Heinrich Ferdinand Nesselmann proposed a distinct language group for Latvian, Lithuanian, and Old Prussian, which he termed Baltic.[11] The term became prevalent after Latvia and Lithuania gained independence in 1918. Up until the early 20th century, either "Latvian" or "Lithuanian" could be used to mean the entire language family.[12]

History

Origins

The Balts or Baltic peoples, defined as speakers of one of the Baltic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family, are descended from a group of Indo-European tribes who settled the area between the lower Vistula and southeast shore of the Baltic Sea and upper Daugava and Dnieper rivers. The Baltic languages, especially Lithuanian, retain a number of conservative or archaic features, perhaps because the areas in which they are spoken are geographically consolidated and have low rates of immigration.[13]

Some of the major authorities on Balts, such as Kazimieras Būga, Max Vasmer, Vladimir Toporov and Oleg Trubachyov,[citation needed] in conducting etymological studies of eastern European river names, were able to identify in certain regions names of specifically Baltic provenance, which most likely indicate where the Balts lived in prehistoric times. According to Vladimir Toporov and Oleg Trubachyov, the eastern boundary of the Balts in the prehistoric times were the upper reaches of the Volga, Moskva, and Oka rivers, while the southern border was the Seym river.[14] This information is summarized and synthesized by Marija Gimbutas in The Balts (1963) to obtain a likely proto-Baltic homeland. Its borders are approximately: from a line on the Pomeranian coast eastward to include or nearly include the present-day sites of Berlin, Warsaw, Kyiv, and Kursk, northward through Moscow to the River Berzha, westward in an irregular line to the coast of the Gulf of Riga, north of Riga.[citation needed]

However, other scholars such as Endre Bojt (1999) reject the presumption that there ever was such a thing as a clear, single "Baltic Urheimat":[15]

'The references to the Balts at various Urheimat locations across the centuries are often of doubtful authenticity, those concerning the Balts furthest to the West are the more trustworthy among them. (...) It is wise to group the particulars of Baltic history according to the interests that moved the pens of the authors of our sources.'[15]

Proto-history

The area of Baltic habitation shrank due to assimilation by other groups, and invasions. According to one of the theories which has gained considerable traction over the years, one of the western Baltic tribes, the Galindians, Galindae, or Goliad, migrated to the area around modern-day Moscow, Russia around the fourth century AD.[16]

Over time the Balts became differentiated into West and East Balts. In the fifth century AD parts of the eastern Baltic coast began to be settled by the ancestors of the Western Balts: Brus/Prūsa ("Old Prussians"), Sudovians/Jotvingians, Scalvians, Nadruvians, and Curonians. The East Balts, including the hypothesised Dniepr Balts, were living in modern-day Belarus, Ukraine and Russia.[citation needed]

Germanic peoples lived to the west of the Baltic homelands; by the first century AD, the Goths had stabilized their kingdom from the mouth of the Vistula, south to Dacia. As Roman domination collapsed in the first half of the first millennium CE in Northern and Eastern Europe, large migrations of the Balts occurred — first, the Galindae or Galindians towards the east, and later, East Balts towards the west. In the eighth century, Slavic tribes from the Volga regions appeared.[17][18][19] By the 13th and 14th centuries, they reached the general area that the present-day Balts and Belarusians inhabit. Many other Eastern and Southern Balts either assimilated with other Balts, or Slavs in the fourth–seventh centuries and were gradually slavicized.[20]

Middle Ages

In the 12th and 13th centuries, internal struggles and invasions by Ruthenians and Poles, and later the expansion of the Teutonic Order, resulted in an almost complete annihilation of the Galindians, Curonians, and Yotvingians.[citation needed] Gradually, Old Prussians became Germanized or Lithuanized between the 15th and 17th centuries, especially after the Reformation in Prussia.[citation needed] The cultures of the Lithuanians and Latgalians/Latvians survived and became the ancestors of the populations of the modern-day countries of Latvia and Lithuania.[citation needed]

Old Prussian was closely related to the other extinct Western Baltic languages, Curonian, Galindian and Sudovian. It is more distantly related to the surviving Eastern Baltic languages, Lithuanian and Latvian. Compare the Prussian word seme (zemē),[21] Latvian zeme, the Lithuanian žemė (land in English).[citation needed]

Culture

| Part of a series on |

| Baltic religion |

|---|

|

The Balts originally practiced Baltic religion. They were gradually Christianized as a result of the Northern Crusades of the Middle Ages. Baltic peoples such as the Latvians, Lithuanians and Old Prussians had their distinct mythologies. The Lithuanians have close historic ties to Poland, and many of them are Roman Catholic. The Latvians have close historic ties to Northern Germany and Scandinavia, and many of them are irreligious. In recent times, the Baltic religion has been revived in Baltic neopaganism.[22][23]

Genetics

The Balts are included in the "North European" gene cluster together with the Germanic peoples, some Slavic groups (the Poles and Northern Russians) and Baltic Finnic peoples.[24]

Saag et a. (2017) detected that the eastern Baltic in the Mesolithic was inhabited primarily by Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs).[25] Their paternal haplogroups were mostly types of I2a and R1b, while their maternal haplogroups were mostly types of U5, U4 and U2.[26] These people carried a high frequency of the derived HERC2 allele which codes for light eye color and possess an increased frequency of the derived alleles for SLC45A2 and SLC24A5, coding for lighter skin color.[27]

Baltic hunter-gatherers still displayed a slightly larger amount of WHG ancestry than Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers (SHGs). WHG ancestry in the Baltic was particularly high among hunter-gatherers in Latvia and Lithuania.[27] Unlike other parts of Europe, the hunter-gatherers of the eastern Baltic do not appear to have mixed much with Early European Farmers (EEFs) arriving from Anatolia.[28]

During the Neolithic, increasing admixture from Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) is detected. The paternal haplogroups of EHGs was mostly types of R1a, while their maternal haplogroups appears to have been almost exclusively types of U5, U4, and U2.[citation needed]

The rise of the Corded Ware culture in the eastern Baltic in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age is accompanied by a significant infusion of steppe ancestry and EEF ancestry into the eastern Baltic gene pool.[28][25][29] In the aftermath of the Corded Ware expansion, local hunter-gatherer ancestry experienced a resurgence.[27]

Haplogroup N reached the eastern Baltic only in the Late Bronze Age, probably with the speakers of the Uralic languages.[27]

Modern-day Balts have a lower amount of EEF ancestry, and a higher amount of WHG ancestry, than any other population in Europe.[30][a]

List of Baltic peoples

Modern-day Baltic peoples

- East Baltic peoples[31]

- Latvians

- Lithuanians

- Aukštaitija ("highlanders")

- Samogitians ("lowlanders")

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "Lietuviai Pasaulyje" (PDF), osp.stat.gov.lt

- ^ Latvian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Rodiklių duomenų bazė - Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt.

- ^ "Iedzīvotāji pēc tautības gada sākumā 1935 - 2023". data.stat.gov.lv.

- ^ Bojtár page 18.

- ^ a b Bojtár page 9.

- ^ Adam of Bremen reports that he followed the local use of balticus from baelt ("belt") because the sea stretches to the east "in modum baltei" ("in the manner of a belt"). This is the first reference to "the Baltic or Barbarian Sea, a day's journey from Hamburg. Bojtár cites Bremensis I,60 and IV,10.

- ^ Balcia, Abalcia, Abalus, Basilia, Balisia. However, apart from poor transcription, there are known [sic] linguistic rule whereby these words, including Balcia, might become "Baltia."

- ^ Bojtár page 10.

- ^ Butler, Ralph (1919). The New Eastern Europe. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 3, 21, 22, 2 24.

- ^ Schmalstieg, William R. (Fall 1987). "A. Sabaliauskas. Mes Baltai (We Balts)". Lituanus. 33 (3). Lituanus Foundation Incorporated. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-06. Book review.

- ^ Bojtár page 11.

- ^ PIECHNIK, IWONA. "FACTORS INFLUENCING CONSERVATISM AND PURISM IN LANGUAGES OF NORTHERN EUROPE (NORDIC, BALTIC, FINNIC)". Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis. doi:10.4467/20834624SL.14.022.2729. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (2015-04-29). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. p. 456. ISBN 978-1-134-92186-7.

- ^ a b Bojt, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 81, 113. ISBN 9789639116429. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Tarasov I. The balts in the Migration Period. P. I. Galindians, pp. 96, 100-112.

- ^ Engel, Barbara Alpern; Martin, Janet (2015). Russia in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-023943-5.

Slavic tribes had reached the territories of the Finns and Balts in the eighth century.

- ^ Gleason, Abbott (2014). A Companion to Russian History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-118-73000-3.

moved ... to the Baltic in the eighth-ninth centuries

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1971). The Slavs (Ancient Peoples and Places, Vol. 74). Thames and Hudson. p. 97. ISBN 0500020728.

no finds of Slavic character can be identified before the eighth century

- ^ Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (2000), Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew (ed.), "The Slavs", The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentary Civilization vs. “Barbarian” and Nomad, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 133–149, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-61837-8_8, ISBN 978-1-349-61837-8, retrieved 2024-08-31

- ^ Mikkels Klussis. Bāziscas prûsiskai-laîtawiskas wirdeîns per tālaisin laksikis rekreaciônin Donelaitis.vdu.lt (Lithuanian version of Donelaitis.vdu.lt).

- ^ Hanley, Monika. (2010-10-21). "Baltic diaspora and the rise of Neo-Paganism". The Baltic Times.

- ^ Naylor, Aliide. (May 31, 2019). "Soviet power gone, Baltic countries' historic pagan past re-emerges". Religion News Service.

- ^ Balanovsky & Rootsi 2008, pp. 236–250.

- ^ a b Saag 2017.

- ^ Mathieson 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Mittnik 2018.

- ^ a b Jones 2017.

- ^ Malmström 2019.

- ^ Lazaridis 2014.

- ^ Kessler, P. L. "Kingdoms of Eastern Europe - Lithuania". The History Files. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

Sources

English language

- Jones, Eppie R. (February 20, 2017). "The Neolithic Transition in the Baltic Was Not Driven by Admixture with Early European Farmers". Current Biology. 27 (4). Cell Press: 576–582. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.060. PMC 5321670. PMID 28162894.

- Balanovsky, Oleg; Rootsi, Siiri; et al. (January 2008). "Two sources of the Russian patrilineal heritage in their Eurasian context". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–250. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 789–791.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (September 17, 2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. hdl:11336/30563. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Malmström, Helena (October 9, 2019). "The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 286 (1912). Royal Society: 20191528. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1528. PMC 6790770. PMID 31594508.

- Mathieson, Iain (February 21, 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Mittnik, Alisa (January 30, 2018). "The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region". Nature Communications. 16 (1): 442. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..442M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02825-9. PMC 5789860. PMID 29382937.

- Saag, Lehti (July 24, 2017). "Extensive Farming in Estonia Started through a Sex-Biased Migration from the Steppe". Current Biology. 27 (14). Cell Press: 2185–2193. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.022. PMID 28712569.

Polish language

- "Bałtowie". Encyklopedia Internetowa PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on April 26, 2005. Retrieved May 25, 2005.

- Antoniewicz, Jerzy; Aleksander Gieysztor (1979). Bałtowie zachodni w V w. p. n. e. – V w. n. e. : terytorium, podstawy gospodarcze i społeczne plemion prusko-jaćwieskich i letto-litewskich (in Polish). Olsztyn-Białystok: Pojezierze. ISBN 83-7002-001-1.

- Kosman, Marceli (1981). Zmierzch Perkuna czyli ostatni poganie nad Bałtykiem (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza.

- "Bałtowie". Wielka Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish) (1 ed.). 2001.

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Łucja (1983). Życie codzienne Prusów i Jaćwięgów w wiekach średnich (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Čepienė, Irena (2000). Historia litewskiej kultury etnicznej (in Polish). Kaunas, "Šviesa". ISBN 5-430-02902-5.

Further reading

- (in Lithuanian) E. Jovaiša, Aisčiai. Kilmė (Aestii. The Origin). Lietuvos edukologijos universiteto leidykla, Vilnius; 2013. ISBN 978-9955-20-779-5

- (in Lithuanian) E. Jovaiša, Aisčiai. Raida (Aestii. The Evolution). Lietuvos edukologijos universiteto leidykla, Vilnius; 2014. ISBN 9789955209577

- (in Lithuanian) E. Jovaiša, Aisčiai. Lietuvių ir Lietuvos pradžia (Aestii. The Beginning of Lithuania and Lithuanians). Lietuvos edukologijos universiteto leidykla, Vilnius; 2016. ISBN 9786094710520

- Nowakowski, Wojciech; Bartkiewicz, Katarzyna. "Baltes et proto-Slaves dans l'Antiquité. Textes et archéologie". In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne, vol. 16, n°1, 1990. pp. 359–402. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/dha.1990.1472];[www.persee.fr/doc/dha_0755-7256_1990_num_16_1_1472]

- Matthews, W. K. "Baltic origins." Revue des études slaves 24.1/4 (1948): 48–59.

External links

- Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. London, New York: Thames & Hudson, Gabriella. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-06. E-book of the original.

- Baranauskas, Tomas (2003). "Forum of Lithuanian History". Historija.net. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- Sabaliauskas, Algirdas (1998). "We, the Balts". Postilla 400. Samogitian Cultural Association. Archived from the original on 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- Straižys, Vytautas; Libertas Klimka (1997). "The Cosmology of ancient Balts". www.astro.lt. Retrieved 2008-09-05.