BERT (language model)

| Original author(s) | Google AI |

|---|---|

| Initial release | October 31, 2018 |

| Repository | github |

| Type | |

| License | Apache 2.0 |

| Website | arxiv |

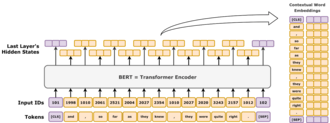

Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) is a language model introduced in October 2018 by researchers at Google.[1][2] It learns to represent text as a sequence of vectors using self-supervised learning. It uses the encoder-only transformer architecture. It is notable for its dramatic improvement over previous state-of-the-art models, and as an early example of a large language model. As of 2020, BERT is a ubiquitous baseline in natural language processing (NLP) experiments.[3]

BERT is trained by masked token prediction and next sentence prediction. As a result of this training process, BERT learns contextual, latent representations of tokens in their context, similar to ELMo and GPT-2.[4] It found applications for many natural language processing tasks, such as coreference resolution and polysemy resolution.[5] It is an evolutionary step over ELMo, and spawned the study of "BERTology", which attempts to interpret what is learned by BERT.[3]

BERT was originally implemented in the English language at two model sizes, BERTBASE (110 million parameters) and BERTLARGE (340 million parameters). Both were trained on the Toronto BookCorpus[6] (800M words) and English Wikipedia (2,500M words). The weights were released on GitHub.[7] On March 11, 2020, 24 smaller models were released, the smallest being BERTTINY with just 4 million parameters.[7]

Architecture

BERT is an "encoder-only" transformer architecture. At a high level, BERT consists of 4 modules:

- Tokenizer: This module converts a piece of English text into a sequence of integers ("tokens").

- Embedding: This module converts the sequence of tokens into an array of real-valued vectors representing the tokens. It represents the conversion of discrete token types into a lower-dimensional Euclidean space.

- Encoder: a stack of Transformer blocks with self-attention, but without causal masking.

- Task head: This module converts the final representation vectors into one-hot encoded tokens again by producing a predicted probability distribution over the token types. It can be viewed as a simple decoder, decoding the latent representation into token types, or as an "un-embedding layer".

The task head is necessary for pre-training, but it is often unnecessary for so-called "downstream tasks," such as question answering or sentiment classification. Instead, one removes the task head and replaces it with a newly initialized module suited for the task, and finetune the new module. The latent vector representation of the model is directly fed into this new module, allowing for sample-efficient transfer learning.[1][8]

Embedding

This section describes the embedding used by BERTBASE. The other one, BERTLARGE, is similar, just larger.

The tokenizer of BERT is WordPiece, which is a sub-word strategy like byte pair encoding. Its vocabulary size is 30,000, and any token not appearing in its vocabulary is replaced by [UNK] ("unknown").

The first layer is the embedding layer, which contains three components: token type embeddings, position embeddings, and segment type embeddings.

- Token type: The token type is a standard embedding layer, translating a one-hot vector into a dense vector based on its token type.

- Position: The position embeddings are based on a token's position in the sequence. BERT uses absolute position embeddings, where each position in sequence is mapped to a real-valued vector. Each dimension of the vector consists of a sinusoidal function that takes the position in the sequence as input.

- Segment type: Using a vocabulary of just 0 or 1, this embedding layer produces a dense vector based on whether the token belongs to the first or second text segment in that input. In other words, type-1 tokens are all tokens that appear after the

[SEP]special token. All prior tokens are type-0.

The three embedding vectors are added together representing the initial token representation as a function of these three pieces of information. After embedding, the vector representation is normalized using a LayerNorm operation, outputting a 768-dimensional vector for each input token. After this, the representation vectors are passed forward through 12 Transformer encoder blocks, and are decoded back to 30,000-dimensional vocabulary space using a basic affine transformation layer.

Architectural family

The encoder stack of BERT has 2 free parameters: , the number of layers, and , the hidden size. There are always self-attention heads, and the feed-forward/filter size is always . By varying these two numbers, one obtains an entire family of BERT models.[9]

For BERT

- the feed-forward size and filter size are synonymous. Both of them denote the number of dimensions in the middle layer of the feed-forward network.

- the hidden size and embedding size are synonymous. Both of them denote the number of real numbers used to represent a token.

The notation for encoder stack is written as L/H. For example, BERTBASE is written as 12L/768H, BERTLARGE as 24L/1024H, and BERTTINY as 2L/128H.

Training

Pre-training

BERT was pre-trained simultaneously on two tasks.[10]

Masked language modeling

In masked language modeling, 15% of tokens would be randomly selected for masked-prediction task, and the training objective was to predict the masked token given its context. In more detail, the selected token is

- replaced with a

[MASK]token with probability 80%, - replaced with a random word token with probability 10%,

- not replaced with probability 10%.

The reason not all selected tokens are masked is to avoid the dataset shift problem. The dataset shift problem arises when the distribution of inputs seen during training differs significantly from the distribution encountered during inference. A trained BERT model might be applied to word representation (like Word2Vec), where it would be run over sentences not containing any [MASK] tokens. It is later found that more diverse training objectives are generally better.[11]

As an illustrative example, consider the sentence "my dog is cute". It would first be divided into tokens like "my1 dog2 is3 cute4". Then a random token in the sentence would be picked. Let it be the 4th one "cute4". Next, there would be three possibilities:

- with probability 80%, the chosen token is masked, resulting in "my1 dog2 is3

[MASK]4"; - with probability 10%, the chosen token is replaced by a uniformly sampled random token, such as "happy", resulting in "my1 dog2 is3 happy4";

- with probability 10%, nothing is done, resulting in "my1 dog2 is3 cute4".

After processing the input text, the model's 4th output vector is passed to its decoder layer, which outputs a probability distribution over its 30,000-dimensional vocabulary space.

Next sentence prediction

Given two spans of text, the model predicts if these two spans appeared sequentially in the training corpus, outputting either [IsNext] or [NotNext]. The first span starts with a special token [CLS] (for "classify"). The two spans are separated by a special token [SEP] (for "separate"). After processing the two spans, the 1-st output vector (the vector coding for [CLS]) is passed to a separate neural network for the binary classification into [IsNext] and [NotNext].

- For example, given "

[CLS]my dog is cute[SEP]he likes playing" the model should output token[IsNext]. - Given "

[CLS]my dog is cute[SEP]how do magnets work" the model should output token[NotNext].

Fine-tuning

- Sentiment classification

- Sentence classification

- Answering multiple-choice questions

BERT is meant as a general pretrained model for various applications in natural language processing. That is, after pre-training, BERT can be fine-tuned with fewer resources on smaller datasets to optimize its performance on specific tasks such as natural language inference and text classification, and sequence-to-sequence-based language generation tasks such as question answering and conversational response generation.[12]

The original BERT paper published results demonstrating that a small amount of finetuning (for BERTLARGE, 1 hour on 1 Cloud TPU) allowed it to achieved state-of-the-art performance on a number of natural language understanding tasks:[1]

- GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation) task set (consisting of 9 tasks);

- SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset[13]) v1.1 and v2.0;

- SWAG (Situations With Adversarial Generations[14]).

In the original paper, all parameters of BERT are finetuned, and recommended that, for downstream applications that are text classifications, the output token at the [CLS] input token is fed into a linear-softmax layer to produce the label outputs.[1]

The original code base defined the final linear layer as a "pooler layer", in analogy with global pooling in computer vision, even though it simply discards all output tokens except the one corresponding to [CLS] .[15]

Cost

BERT was trained on the BookCorpus (800M words) and a filtered version of English Wikipedia (2,500M words) without lists, tables, and headers.[16]

Training BERTBASE on 4 cloud TPU (16 TPU chips total) took 4 days, at an estimated cost of 500 USD.[7] Training BERTLARGE on 16 cloud TPU (64 TPU chips total) took 4 days.[1]

Interpretation

Language models like ELMo, GPT-2, and BERT, spawned the study of "BERTology", which attempts to interpret what is learned by these models. Their performance on these natural language understanding tasks are not yet well understood.[3][17][18] Several research publications in 2018 and 2019 focused on investigating the relationship behind BERT's output as a result of carefully chosen input sequences,[19][20] analysis of internal vector representations through probing classifiers,[21][22] and the relationships represented by attention weights.[17][18]

The high performance of the BERT model could also be attributed[citation needed] to the fact that it is bidirectionally trained. This means that BERT, based on the Transformer model architecture, applies its self-attention mechanism to learn information from a text from the left and right side during training, and consequently gains a deep understanding of the context. For example, the word fine can have two different meanings depending on the context (I feel fine today, She has fine blond hair). BERT considers the words surrounding the target word fine from the left and right side.

However it comes at a cost: due to encoder-only architecture lacking a decoder, BERT can't be prompted and can't generate text, while bidirectional models in general do not work effectively without the right side, thus being difficult to prompt. As an illustrative example, if one wishes to use BERT to continue a sentence fragment "Today, I went to", then naively one would mask out all the tokens as "Today, I went to [MASK] [MASK] [MASK] ... [MASK] ." where the number of [MASK] is the length of the sentence one wishes to extend to. However, this constitutes a dataset shift, as during training, BERT has never seen sentences with that many tokens masked out. Consequently, its performance degrades. More sophisticated techniques allow text generation, but at a high computational cost.[23]

History

BERT was originally published by Google researchers Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. The design has its origins from pre-training contextual representations, including semi-supervised sequence learning,[24] generative pre-training, ELMo,[25] and ULMFit.[26] Unlike previous models, BERT is a deeply bidirectional, unsupervised language representation, pre-trained using only a plain text corpus. Context-free models such as word2vec or GloVe generate a single word embedding representation for each word in the vocabulary, whereas BERT takes into account the context for each occurrence of a given word. For instance, whereas the vector for "running" will have the same word2vec vector representation for both of its occurrences in the sentences "He is running a company" and "He is running a marathon", BERT will provide a contextualized embedding that will be different according to the sentence.[4]

On October 25, 2019, Google announced that they had started applying BERT models for English language search queries within the US.[27] On December 9, 2019, it was reported that BERT had been adopted by Google Search for over 70 languages.[28][29] In October 2020, almost every single English-based query was processed by a BERT model.[30]

Variants

The BERT models were influential and inspired many variants.

RoBERTa (2019)[31] was an engineering improvement. It preserves BERT's architecture (slightly larger, at 355M parameters), but improves its training, changing key hyperparameters, removing the next-sentence prediction task, and using much larger mini-batch sizes.

DistilBERT (2019) distills BERTBASE to a model with just 60% of its parameters (66M), while preserving 95% of its benchmark scores.[32][33] Similarly, TinyBERT (2019)[34] is a distilled model with just 28% of its parameters.

ALBERT (2019)[35] used shared-parameter across layers, and experimented with independently varying the hidden size and the word-embedding layer's output size as two hyperparameters. They also replaced the next sentence prediction task with the sentence-order prediction (SOP) task, where the model must distinguish the correct order of two consecutive text segments from their reversed order.

ELECTRA (2020)[36] applied the idea of generative adversarial networks to the MLM task. Instead of masking out tokens, a small language model generates random plausible plausible substitutions, and a larger network identify these replaced tokens. The small model aims to fool the large model.

DeBERTa

DeBERTa (2020)[37] is a significant architectural variant, with disentangled attention. Its key idea is to treat the positional and token encodings separately throughout the attention mechanism. Instead of combining the positional encoding () and token encoding () into a single input vector (), DeBERTa keeps them separate as a tuple: (). Then, at each self-attention layer, DeBERTa computes three distinct attention matrices, rather than the single attention matrix used in BERT:[note 1]

| Attention type | Query type | Key type | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content-to-content | Token | Token | "European"; "Union", "continent" |

| Content-to-position | Token | Position | [adjective]; +1, +2, +3 |

| Position-to-content | Position | Token | -1; "not", "very" |

The three attention matrices are added together element-wise, then passed through a softmax layer and multiplied by a projection matrix.

Absolute position encoding is included in the final self-attention layer as additional input.

Notes

- ^ The position-to-position type was omitted by the authors for being useless.

References

- ^ a b c d e Devlin, Jacob; Chang, Ming-Wei; Lee, Kenton; Toutanova, Kristina (October 11, 2018). "BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding". arXiv:1810.04805v2 [cs.CL].

- ^ "Open Sourcing BERT: State-of-the-Art Pre-training for Natural Language Processing". Google AI Blog. November 2, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Anna; Kovaleva, Olga; Rumshisky, Anna (2020). "A Primer in BERTology: What We Know About How BERT Works". Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 8: 842–866. arXiv:2002.12327. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00349. S2CID 211532403.

- ^ a b Ethayarajh, Kawin (September 1, 2019), How Contextual are Contextualized Word Representations? Comparing the Geometry of BERT, ELMo, and GPT-2 Embeddings, arXiv:1909.00512

- ^ Anderson, Dawn (November 5, 2019). "A deep dive into BERT: How BERT launched a rocket into natural language understanding". Search Engine Land. Retrieved August 6, 2024.

- ^ name="bookcorpus"Zhu, Yukun; Kiros, Ryan; Zemel, Rich; Salakhutdinov, Ruslan; Urtasun, Raquel; Torralba, Antonio; Fidler, Sanja (2015). "Aligning Books and Movies: Towards Story-Like Visual Explanations by Watching Movies and Reading Books". pp. 19–27. arXiv:1506.06724 [cs.CV].

- ^ a b c "BERT". GitHub. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Zhang, Tianyi; Wu, Felix; Katiyar, Arzoo; Weinberger, Kilian Q.; Artzi, Yoav (March 11, 2021), Revisiting Few-sample BERT Fine-tuning, arXiv:2006.05987

- ^ Turc, Iulia; Chang, Ming-Wei; Lee, Kenton; Toutanova, Kristina (September 25, 2019), Well-Read Students Learn Better: On the Importance of Pre-training Compact Models, arXiv:1908.08962

- ^ "Summary of the models — transformers 3.4.0 documentation". huggingface.co. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Tay, Yi; Dehghani, Mostafa; Tran, Vinh Q.; Garcia, Xavier; Wei, Jason; Wang, Xuezhi; Chung, Hyung Won; Shakeri, Siamak; Bahri, Dara (February 28, 2023), UL2: Unifying Language Learning Paradigms, arXiv:2205.05131

- ^ a b Zhang, Aston; Lipton, Zachary; Li, Mu; Smola, Alexander J. (2024). "11.9. Large-Scale Pretraining with Transformers". Dive into deep learning. Cambridge New York Port Melbourne New Delhi Singapore: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-38943-3.

- ^ Rajpurkar, Pranav; Zhang, Jian; Lopyrev, Konstantin; Liang, Percy (October 10, 2016). "SQuAD: 100,000+ Questions for Machine Comprehension of Text". arXiv:1606.05250 [cs.CL].

- ^ Zellers, Rowan; Bisk, Yonatan; Schwartz, Roy; Choi, Yejin (August 15, 2018). "SWAG: A Large-Scale Adversarial Dataset for Grounded Commonsense Inference". arXiv:1808.05326 [cs.CL].

- ^ "bert/modeling.py at master · google-research/bert". GitHub. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

bookcorpuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Kovaleva, Olga; Romanov, Alexey; Rogers, Anna; Rumshisky, Anna (November 2019). "Revealing the Dark Secrets of BERT". Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). pp. 4364–4373. doi:10.18653/v1/D19-1445. S2CID 201645145.

- ^ a b Clark, Kevin; Khandelwal, Urvashi; Levy, Omer; Manning, Christopher D. (2019). "What Does BERT Look at? An Analysis of BERT's Attention". Proceedings of the 2019 ACL Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics: 276–286. arXiv:1906.04341. doi:10.18653/v1/w19-4828.

- ^ Khandelwal, Urvashi; He, He; Qi, Peng; Jurafsky, Dan (2018). "Sharp Nearby, Fuzzy Far Away: How Neural Language Models Use Context". Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics: 284–294. arXiv:1805.04623. doi:10.18653/v1/p18-1027. S2CID 21700944.

- ^ Gulordava, Kristina; Bojanowski, Piotr; Grave, Edouard; Linzen, Tal; Baroni, Marco (2018). "Colorless Green Recurrent Networks Dream Hierarchically". Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers). Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. pp. 1195–1205. arXiv:1803.11138. doi:10.18653/v1/n18-1108. S2CID 4460159.

- ^ Giulianelli, Mario; Harding, Jack; Mohnert, Florian; Hupkes, Dieuwke; Zuidema, Willem (2018). "Under the Hood: Using Diagnostic Classifiers to Investigate and Improve how Language Models Track Agreement Information". Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics: 240–248. arXiv:1808.08079. doi:10.18653/v1/w18-5426. S2CID 52090220.

- ^ Zhang, Kelly; Bowman, Samuel (2018). "Language Modeling Teaches You More than Translation Does: Lessons Learned Through Auxiliary Syntactic Task Analysis". Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics: 359–361. doi:10.18653/v1/w18-5448.

- ^ Patel, Ajay; Li, Bryan; Mohammad Sadegh Rasooli; Constant, Noah; Raffel, Colin; Callison-Burch, Chris (2022). "Bidirectional Language Models Are Also Few-shot Learners". arXiv:2209.14500 [cs.LG].

- ^ Dai, Andrew; Le, Quoc (November 4, 2015). "Semi-supervised Sequence Learning". arXiv:1511.01432 [cs.LG].

- ^ Peters, Matthew; Neumann, Mark; Iyyer, Mohit; Gardner, Matt; Clark, Christopher; Lee, Kenton; Luke, Zettlemoyer (February 15, 2018). "Deep contextualized word representations". arXiv:1802.05365v2 [cs.CL].

- ^ Howard, Jeremy; Ruder, Sebastian (January 18, 2018). "Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification". arXiv:1801.06146v5 [cs.CL].

- ^ Nayak, Pandu (October 25, 2019). "Understanding searches better than ever before". Google Blog. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "Understanding searches better than ever before". Google. October 25, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2024.

- ^ Montti, Roger (December 10, 2019). "Google's BERT Rolls Out Worldwide". Search Engine Journal. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "Google: BERT now used on almost every English query". Search Engine Land. October 15, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Liu, Yinhan; Ott, Myle; Goyal, Naman; Du, Jingfei; Joshi, Mandar; Chen, Danqi; Levy, Omer; Lewis, Mike; Zettlemoyer, Luke; Stoyanov, Veselin (2019). "RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach". arXiv:1907.11692 [cs.CL].

- ^ Sanh, Victor; Debut, Lysandre; Chaumond, Julien; Wolf, Thomas (February 29, 2020), DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter, arXiv:1910.01108

- ^ "DistilBERT". huggingface.co. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- ^ Jiao, Xiaoqi; Yin, Yichun; Shang, Lifeng; Jiang, Xin; Chen, Xiao; Li, Linlin; Wang, Fang; Liu, Qun (October 15, 2020), TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for Natural Language Understanding, arXiv:1909.10351

- ^ Lan, Zhenzhong; Chen, Mingda; Goodman, Sebastian; Gimpel, Kevin; Sharma, Piyush; Soricut, Radu (February 8, 2020), ALBERT: A Lite BERT for Self-supervised Learning of Language Representations, arXiv:1909.11942

- ^ Clark, Kevin; Luong, Minh-Thang; Le, Quoc V.; Manning, Christopher D. (March 23, 2020), ELECTRA: Pre-training Text Encoders as Discriminators Rather Than Generators, arXiv:2003.10555

- ^ He, Pengcheng; Liu, Xiaodong; Gao, Jianfeng; Chen, Weizhu (October 6, 2021), DeBERTa: Decoding-enhanced BERT with Disentangled Attention, arXiv:2006.03654

Further reading

- Rogers, Anna; Kovaleva, Olga; Rumshisky, Anna (2020). "A Primer in BERTology: What we know about how BERT works". arXiv:2002.12327 [cs.CL].