Attacks on the United States (1900–1945)

| Attacks on the United States |

|---|

| 1776–1899, 1900–1945, 1946–1999, 2000–present |

The United States has been attacked several times throughout its history including attacks on its states and territories, embassies and consulates, and on its military. Attacks against the United States include invasions, military offensives, raids, bombardment and airstrikes on it's military, terrorist bombings and shootings, and any other deliberate act of violence against the United States government or military.

Between 1900–1945 the United States was attacked numerous times during World War I and World War II, six times along the Mexico–United States border from various conflicts in Mexico, and once each in Nicaragua and in Iran.

Mexican Border War / Bandit War (November 1910–June 1919)

First Battle of Agua Prieta

The First Battle of Agua Prieta was fought on August 13–14, 1911, between the supporters of Francisco Madero and federal troops of Porfirio Díaz during the Mexican Revolution at the Mexico–United States border town of Agua Prieta, Mexico. During the course of the battle, U.S. troops stationed in the Douglas, Arizona right across border were fired upon by federal troops under Díaz.[1] As a result of being attacked, the Americans responded by intervening in the battle, which allowed the rebels to briefly take control of the town.[2][3] One American was killed and 13 other Americans were injured during the battle's spill-over into Douglas.[4]

Ojo de Agua Raid

Battle of Nogales

Raid on Glenn Springs

Occupation of Nicaragua (August 1912–1916)

The Battle of Masaya on September 19, 1912, was an engagement during the first U.S. occupation of Nicaragua, fought between U.S. Marines and sailors, led by General Smedley Butler and Nicaraguan rebels, led by Benjamín Zeledón. The United States government sent an expedition of 400 U.S. Marines and sailors, plus "a pair of Colts and 3-inch guns, to seize the city of Granada, Nicaragua from rebel forced. Traveling by train, Butler's forces reached the outskirts of Masaya, where they were threatened by rebels atop the hills of Coyotepe and Barranca. The Americans negotiated with Zeledón for safe passage past the two imposing hills. On September 19, the Americans continued their journey into the city of Masaya, with Butler, "legs dangling," sitting at the front of the train on a flatcar placed in front of the engine. The train had nearly gotten through the town, when, at Nindiri Station, the Americans were confronted by two mounted Nicaraguans. These two men, possibly drunk, opened fire with pistols, striking Corporal J. J. Bourne, who was next to Butler, in the finger. Butler had the train stopped, so a corpsman could be summoned to aid Bourne. Before long, snipers in the houses on both sides of the railroad track and 150 "armed horsemen" began shooting at the American forces. The American forces then returned fire. The most intense period of fighting lasted five minutes, "then [the firing] gradually died out." During the battle, six Americans were wounded and three others were captured by the rebels.[7][8]

World War I (April 1915–November 1918)

Bombing of the SS Cushing

On April 29, 1915, the SS Cushing, an American commercial steamship belonging to Standard Oil, was attacked by naval aviators of the German Empire. At the time of the attack, the Cushing was carrying a shipment of petroleum from New York City to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. German naval bombers dropped three bombs at the Cushing, with one hitting the ship causing damage. This was the first time the United States was attacked during World War I.[9][10]

Sinking of the SS Gulflight

The sinking of the SS Gulflight occurred on May 1, 1915, during World War I. The Gulflight, an American oil tanker owned by the Gulf Refining Company, left Port Arthur, Texas on April 10 carrying a cargo of gasoline in the ship's tanks and barrels of lubricating oil to Rouen, France.[11][12] At a point 22 nautical miles (41 km) west of the Bishop Rock lighthouse, Isles of Scilly, at 11 a.m. on 1 May, Gulflight was challenged by two British patrol vessels, HMS Iago and HMS Filey, which queried her destination. The patrol ships had been searching for a submarine which had been sinking ships in the area over the last couple of days. The patrol vessels were not satisfied with Gulflight's papers and suspected her of refuelling the U-boat, so ordered the tanker to accompany them into port.[13] The patrol ships took up station one on either side of Gulflight, Iago close on the starboard side and Filey further ahead on the port. At 12:50 p.m., on May 1, 1915, while off the Isles of Scilly in the North Atlantic, the German U-boat U-30 fired a torpedo at the Gulflight, which was flying an American flag. The torpedo struck Gulflight, causing it to sink. The crew abandoned ship, and were taken on board by the patrol ship Iago which turned towards St Mary's island. While abandoning the ship, two crew members died while jumping into the water. At about 2:30 a.m., Captain Gunter from Gulflight was taken ill and died around 3:40 a.m. from a heart attack.[14]

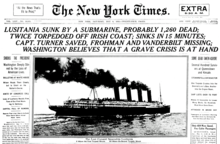

Sinking of the RMS Lusitania

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania occurred on May 7, 1915, during World War I, when the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-20 off the southern coast of Ireland near the Old Head of Kinsale. The Lusitania, operated by the Cunard Line, was on a transatlantic voyage from New York City to Liverpool, carrying 1,959 passengers and crew, including men, women, and children from various countries. The ship was struck by a single torpedo on its starboard side, causing a secondary explosion believed to be from munitions stored in the cargo hold. This devastating blast caused the Lusitania to sink in just 18 minutes, plunging the majority of the vessel beneath the waves before many lifeboats could be launched. Of the 1,959 people on board, 1,198 died, including 128 Americans.

The German Empire had declared the waters around the British Isles a war zone and issued warnings that ships sailing through the area could be attacked. Despite these warnings, the Lusitania continued its route, relying on its speed and the belief that passenger liners would not be targeted. The incident caused a global outcry, particularly in Britain and the United States, where public opinion turned sharply against Germany. The sinking became a powerful propaganda tool for the Allies, portraying the Germans as ruthless aggressors. Although the U.S. did not immediately enter the war, the loss of American lives strained diplomatic relations and intensified calls for action. The sinking of the RMS Lusitania remains one of the deadliest maritime tragedies in history and is often cited as a key event that ultimately led the United States to declare war on Germany in April 1917, marking a turning point in World War I. The ship's sinking continues to be a subject of historical investigation, with debates about whether it was a legitimate military target due to its cargo of munitions and whether the British government used the incident to draw the United States into the war.[16][17][18]

United States Capitol bomb attack

On July 2, 1915, Eric Muenter, a German-American political terrorist and professor at Harvard University working for the German Empire, began a campaign against the United States, by hiding a package containing three sticks of dynamite with a timing mechanism set for nearly midnight under a telephone switchboard in the Senate reception room in the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.. The bomb exploded at approximately 11:40 pm, resulting in no casualties. Muenter wrote a letter to The Washington Star under a pseudonym R. Pearce, explaining his actions, which were published after the bombing. He said he hoped the explosion would "make enough noise to be heard above the voices that clamor for war. This explosion is an exclamation point in my appeal for peace."[19][20][21]

Black Tom explosion

On July 30, 1916, during World War I, a series of explosions destroyed over two million pounds of munitions at a depot on Black Tom Island in Jersey City, New Jersey. The attack, carried out by agents of the German Empire, targeted ammunition shipments to Allied forces in Europe. The explosion injured hundreds, killed between four and seven people, and caused an estimated $20 million in damages (equivalent to over $500 million today). The incident marked one of the largest acts of sabotage on U.S. soil.[22]

January 1917 German Crown Council meeting

On January 9, 1917, the German Crown Council had a meeting, presided over by German Emperor Wilhelm II, which decided on the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by the Imperial German Navy during World War I. Immediately following the announcement of unrestricted submarine warfare, which was made public on January 31, the United States public opinion was immediately in favor of joining the war against the German Empire. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked a special joint session of the United States Congress for a declaration of war against the German Empire. Congress responded with the declaration on April 6. Between January 9–April 6, 1917, the German Empire sank ten American merchant ships.[23][24]

Sinking of the SS Santa Maria

On February 25, 1918, while traveling in convoy HH42, the SS Santa Maria, a tanker owned by Sun Co., Inc. was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-19 while off the coast of Lough Swilly, County Donegal, United Kingdom. The crew successfully abandoned ship and survived the attack.[25]

Sinking of the SS Carolina

On June 2, 1918, the 380-foot-long (120 m) passenger liner SS Carolina was sunk by the German submarine U-151 while traveling from San Juan to New York. The sinking ultimately resulted in 13 deaths when a motor dory carrying survivors capsized—representing the first civilian casualties of U-boat activity on the US Atlantic seaboard. The attack represented one of six U.S. vessels that sunk on June 2, resulting in the day being deemed "Black Sunday".[26][27]

Attack on Orleans

On July 21, 1918, German submarine U-156 fired on a tugboat convoy 3 miles (5 km) off the coast of Orleans, Massachusetts. During the hour-long battle, the submarine damaged the tugboat Perth Amboy and sank several barges towed by it, while American Curtiss HS seaplanes unsuccessfully attempted to bomb the U-boat. The U.S. Coast Guard rescued all 32 sailors, and there were no casualties. The submarine escaped after firing 147 shells.[28][29][30]

Some shells landed on Nauset Beach, making Orleans the only place in the contiguous United States to receive enemy fire during World War I. It was also the first time that the United States was shelled by artillery of an external power since the Siege of Fort Texas in 1846.[31]

Battle of Columbus (March 1916)

The Battle of Columbus took place on March 9, 1916, when Mexican revolutionary leader Francisco "Pancho" Villa led an early-morning raid against the small U.S. border town of Columbus, New Mexico. Villa's forces, numbering 484, hoped to secure supplies and strike at American soldiers stationed nearby. However, the U.S. 13th Cavalry Regiment quickly rallied and drove the attackers back, inflicting heavy casualties. Although the raid was brief, it had far-reaching consequences, prompting American President Woodrow Wilson to launch the Punitive Expedition into Mexico under General John J. Pershing in a largely unsuccessful effort to capture Villa and stabilize the border region. During the battle, "Pancho" Villa captured and executed 19 American soldiers and another 38 died from wounds during the battle.[32][33][34]

Murder of Robert Whitney Imbrie (July 1924)

An angry mob led by members of the Muslim clergy and including many members of the Iranian Army beat Consul Robert W. Imbrie to death. The mob blamed the United States for poisoning a well.[35]

Bombing of Naco, Arizona (April 1929)

During the 1929 Escobar Rebellion, the town of Naco in Arizona was accidentally bombed by Mexican Federales. While rebel forces were battling the Federales for control of the neighboring town of Naco, Sonora, the Irish-American mercenary and pilot Patrick Murphy was hired to bombard the government forces with improvised explosives dropped from his biplane. During the ensuing fighting, Murphy mistakenly dropped bombs on the American side of the international border on three occasions, causing significant damage to both private and government-owned property, as well as slight injuries to several American spectators watching the battle from across the border. The bombing, although unintentional, is noted for being the first aerial bombardment of the continental United States by a foreign power in history.[36][37][38]

World War II (December 1941–September 1945)

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii, the United States, on Sunday, December 7, 1941. At the time of the attack, the United States was a neutral country in World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor started at 7:48 a.m. Hawaiian time (6:18 p.m. GMT). The base was attacked by 353 Imperial Japanese aircraft (including fighters, level and dive bombers, and torpedo bombers) in two waves, launched from six aircraft carriers. Of the eight United States Navy battleships present, all were damaged and four were sunk. All but the USS Arizona were later raised, and six were returned to service and went on to fight in the war. The Japanese also sank or damaged three cruisers, three destroyers, an anti-aircraft training ship, and one minelayer. More than 180 US aircraft were destroyed. A total of 2,393 Americans were killed and 1,178 others were wounded, making it the deadliest event ever recorded in Hawaii.[39] It was also the deadliest foreign attack against the United States in its history until the September 11 attacks of 2001.[40] Important base installations, such as the power station, dry dock, shipyard, maintenance, and fuel and torpedo storage facilities, as well as the submarine piers and headquarters building (also home of the intelligence section) were not attacked. Japanese losses during the attack were light: 29 aircraft and five midget submarines were lost, and 129 servicemen killed. Kazuo Sakamaki, the commanding officer of one of the submarines, was captured.

Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire later that day (December 8 in Tokyo), but the declarations were not delivered until the following day. The British government declared war on Japan immediately after learning that their territory had also been attacked, while the following day (December 8), the United States Congress declared war on Japan. On December 11, though they had no formal obligation to do so under the Tripartite Pact with Japan, Germany and Italy each declared war on the United States, which responded with a declaration of war against Germany and Italy.

While there were historical precedents for the unannounced military action by Japan, the lack of any formal warning, as required by the Hague Convention of 1907, and the perception that the attack had been unprovoked, led then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the opening line of his speech to a joint session of Congress the following day, to famously label December 7, 1941, "a date which will live in infamy".

Japanese first attack on Midway

On December 7, 1941, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Empire of Japan launched a bombardment of Sand Island in the Midway Atoll, a territory and military base of the United States. Two Japanese destroyers, the IJN Ushio and the IJN Sazanami, which had just finished attacking Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, shelled the American island. The engagement began at 09:31 and lasted 54 minutes, with damage occurring to the American command, communications and power plant building. Battery "H" commander—First Lieutenant George H. Cannon—was hit and killed by shrapnel while inside the command building. Lieutenant Cannon refused medical attention until he was assured that the communications were restored to the post and the wounded marines around him were evacuated. By the time Cannon received aid from a medic, it was too late and he died due to blood loss. For Cannon's "distinguished conduct in the line of his profession, extraordinary courage, and disregard of his own condition", he received the first Medal of Honor issued to a U.S. Marine for actions in the Second World War. Several other buildings on the island were struck during the bombardment, which led to the deaths of four Americans, with ten others being injured. The IJN Ushio fired 109 rounds and the IJN Sazanami fired 193 rounds at Sand Island.[41][42]

Japanese invasion of the Philippines

On December 8, 1941, the Empire of Japan, launched an invasion of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, a territory of the United States.[43][44] The Japanese launched the invasion by sea from Taiwan, over 200 miles (320 km) north of the Philippines, and from Palau to the east, starting with the invasion of Batan Island. The defending forces outnumbered the Japanese by a ratio of 3:2 but were a mixed force of non-combat-experienced regular, national guard, constabulary and newly created Commonwealth units. The Japanese used first-line troops at the outset of the campaign, and by concentrating their forces, they swiftly overran most of Luzon during the first month.

The Japanese high command, believing that they had won the campaign, made a strategic decision to advance by a month their timetable of operations in Borneo and Indonesia and to withdraw their best division and the bulk of their airpower in early January 1942.[45] That, coupled with the defenders' decision to withdraw into a defensive holding position in the Bataan Peninsula and also the defeat of three Japanese battalions at the Battle of the Points and Battle of the Pockets, enabled the Americans and Filipinos to hold out for four more months. After the Japanese failure to penetrate the Bataan defensive perimeter in February, the Japanese conducted a 40-day siege. The crucial large natural harbor and port facilities of Manila Bay were denied to the Japanese until May 1942. Japan's conquest of the Philippines is often considered the worst military defeat in U.S. history.[46] About 23,000 American military personnel and about 100,000 Filipino soldiers were killed or captured.[47]

Japanese invasion of Wake Island

On December 8, simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7 Hawaii time), the Empire of Japan began an attack and invasion of Wake Island, a territory of the United States. The invasion started with a surprise bombing raid on December 8, 1941, within hours of Pearl Harbor, and the air raids continued almost every day for the duration of the battle. There were two amphibious assaults, one on December 11, 1941 (which was rebuffed) and another on December 23, that led to the Japanese capture of the atoll. In addition, there were several air battles above and around Wake and an encounter between two naval vessels. The U.S. lost control of the island and 12 fighter aircraft; in addition to the garrison being taken as prisoners of war, nearly 1200 civilian contractors were also captured by the Japanese. The Japanese lost about two dozen aircraft of different types, four surface vessels, and two submarines as part of the operation, in addition to at least 600 armed forces. It is typically noted that 98 civilian POWs captured in this battle were used for slave labor and then executed on Wake Island in October 1943. The other POWs were deported and sent to prisoner of war camps in Asia, with five executed on the sea voyage.

The island was held by the Japanese for the duration of the Pacific War theater of World War II; the remaining Japanese garrison on the island surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines on 4 September 1945, after the earlier surrender on 2 September 1945 on the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay to General Douglas MacArthur.[48]

Japanese invasion of Guam

On December 8, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched an invasion of the island of Guam in the Mariana Islands, a territory of the United States.[49] At the time of the Japanese invasion, Guam had a population of 23,394, most of whom lived in or within 10 miles (16 km) of the island's capital of Agana, along with an American military garrison consisting of 547 Marines and sailors, along with the USS Gold Star, a U.S. navy freighter, the USS Penguin, a minesweeper, and two wooden-hulled patrol boats (USS YP-16 and USS YP-17). Approximately four hours after learning about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese land-based aircraft began bombing the American garrison on the island. During several bombing attacks on December 8, several buildings on the island had been damaged or destroyed and the USS Penguin had been sunk after it shot down a Japanese aircraft. The Japanese continued bombing missions on December 9. During the day on December 9, a Japanese invasion fleet of four heavy cruisers, four destroyers, two gunboats, six submarine chasers, two minesweepers, two destroyer tenders, and ten transports left Saipan for Guam. A mistake in their intelligence gathering had caused the Japanese to overcommit resources and attack Guam with disproportionate force.

During the early morning hours on December 10, approximately 400 Japanese troops landed at Dungcas Beach, north of Agana. Fighting between the American garrison and the Japanese invasion forces took place for a few hours. At 06:00, George J. McMillin, the American commanding officer formally surrendered to the Japanese forces. A few skirmishes took place all over the island before news of the surrender spread and the rest of the island forces laid down their arms. YP-16 was scuttled by means of fire, and YP-17 was captured by Japanese naval forces. An American freighter was damaged by the Japanese. During the Japanese landings near the American garrison, the Japanese South Seas Detachment (about 5,500 men) under the command of Major General Tomitarō Horii made separate landings at Tumon Bay in the north, on the southwest coast near Merizo, and on the eastern shore of the island at Talofofo Bay. During the invasion, 17 Americans were killed, which included the deaths of 13 civilians, 35 were wounded, and 406 were captured.[50][51] Following their capture of the island, the Japanese began an occupation of Guam.[52]

Bombing of Darwin, Australia

On February 19, 1942, the Empire of Japan conducted a bombing mission on the strategic Allied city of Darwin and Darwin Harbour, northern Australia.[53][54] The Japanese had captured Ambon, Borneo, and Celebes between December 1941 and early-February 1942. Landings on Timor were scheduled for 20 February, and an invasion of Java was planned to take place shortly afterwards. On 10 February a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft overflew the town, and identified an American aircraft carrier (actually the seaplane tender USS Langley), five destroyers, and 21 merchant ships in Darwin Harbour, as well as 30 aircraft at the town's two airfields.[55] In order to protect these landings from Allied (particularly American) interference, the Japanese military command decided to conduct a major air raid on Darwin.[56][55] A total of 65 Allied warships and merchant vessels were in Darwin Harbour at the time of the raids, including several American ships.[57] During the attack, the USS Peary, a destroyer, was sunk and the USS William B. Preston, a seaplane tender was damaged. During the attack, the USAT Meigs and the USAT Mauna Loa were also sunk, the SS Portmar was beached, and the SS Admiral Halstead, was damaged.[58]

Bombardment of Ellwood / "Battle of Los Angeles"

On February 23, 1942, Japanese submarine I-17 under the command of Kozo Nishino, opened fire on the Ellwood Oil Field in California, marking the first shelling of the North American mainland during World War II. At the time of the attack, I-17 had an armament of a 14-cm deck gun, six 20 in (510 mm) torpedo tubes and 17 torpedoes. The Japanese government was concerned about a radio speech scheduled by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt for February 23, 1942, which prompted the order for a Japanese submarine to shell the California coast on that day.[59] At around 7:00 pm, the I-17 came to a stop opposite the Ellwood field on the Gaviota Coast. Nishino ordered the deck gun readied for action. Its crew took aim at a Richfield aviation fuel tank just beyond the beach and opened fire about 15 minutes later with the first rounds landing near a storage facility. The oil field's workmen had mostly left for the day, but a skeleton crew on duty heard the rounds hit. They took it to be an internal explosion until one man spotted the I-17 off the coast. An oiler named G. Brown later told reporters that the enemy submarine looked so big to him he thought it must be a cruiser or a destroyer until he realized that only one gun was firing. Nishino soon ordered his men to aim at the second storage tank. Brown and the others called the police, as the Japanese shells continued to fall around them.

Firing in the dark from a submarine buffeted by waves, it was inevitable that rounds would miss their target. One round passed over Wheeler's Inn, whose owner Laurence Wheeler promptly called the Santa Barbara County Sheriff's Office. A deputy sheriff assured him that warplanes were already on their way, but none arrived. The Japanese shells destroyed a derrick and a pump house, while the Ellwood Pier and a catwalk suffered minor damage. After 20 minutes, the gunners ceased fire and the submarine sailed away. Estimates of the number of explosive shells fired ranged from 12 to 25.[60] Although he caused only light damage, Nishino had achieved his purpose, which was to spread fear along the American west coast.[61][62] A day later, reports of enemy aircraft led to the "Battle of Los Angeles", in which American artillery was discharged over Los Angeles for several hours due to the mistaken belief that the Japanese were invading.[63]

Sinking of the USS Langley

On February 27, 1942, the American aircraft carrier USS Langley was attacked by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, marking the first American aircraft carrier to be attacked during World War II. During the early hours on February 27, the American aircraft carrier USS Langley, rendezvoused with the destroyers USS Whipple and USS Edsall, which had been sent from Tjilatjap, Indonesia to be escorts. Later in the morning, a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft located the formation.

At 11:40, about 75 nautical miles (139 km; 86 mi) south of Tjilatjap, the three ships were attacked by sixteen Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service's Takao Kōkūtai, led by Lieutenant Jiro Adachi, flying out of Denpasar airfield on Bali, and escorted by fifteen A6M2 Reisen fighters. Rather than dropping all their bombs at once, the Japanese bombers attacked releasing partial salvos. Since they were level bombing from medium altitude, the Langley was able to alter helm when the bombs were released and evade the first and second bombing passes, but the bombers changed their tactics on the third pass and bracketed all the directions the Langley could turn. As a result, the USS Langley took five hits from a mix of 60-and-250-kilogram (130 and 550 lb) bombs as well as three near misses, with 16 crewmen killed. The topside burst into flames, steering was impaired, and the Langley developed a 10° list to port. The USS Langley went dead in the water as her engine room flooded. At 13:32, the order to abandon ship was given. After taking off the surviving crew and passengers (Whipple rescued 308 men and Edsall 177) at 13:58, the escorting destroyers stood off and began firing nine 4-inch (100 mm) shells and two torpedoes into Langley's hull at 14:29 to prevent her from falling into enemy hands, scuttling her. A total of 319 from the USS Langley were killed during the Japanese attack.[64][65][66]

Battle of Dutch Harbor

Between June 3–4, 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched two aircraft carrier raids on the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base and U.S. Army Fort Mears at Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island, Alaska, beginning the Aleutian Islands campaign during World War II.[67] In June 1942, a Japanese carrier strike force, under the command of Rear Admiral Kakuji Kakuta, comprising the carriers IJN Ryūjō and the IJN Jun'yō plus escort ships, sailed to 180 mi (160 nmi; 290 km) southwest of Dutch Harbor. Shortly before dawn at 02:58, Admiral Kakuta ordered his aircraft carriers to launch their strike which was made up of 12 A6M Zero fighters, 10 B5N Kate high-level bombers, and 12 D3A Val dive bombers which took off from the two small carriers in the freezing weather to strike at Dutch Harbor. One B5N was lost on takeoff from the IJN Ryujo. Arriving at 04:07, the Japanese planes bombed the radio station and oil tanks, awakening the 206th with explosions and gunfire. Despite being on alert, there was no specific warning for the attack, leaving the American gun crews to improvise. They quickly manned their 3-inch, 37 mm, and .50-caliber guns—and one American even resorted to throwing a wrench. Some reported seeing the aviators' faces on repeated runs. The day's heaviest losses came when bombs struck two barracks, killing 25 servicemen.

During the evening of June 3–4, the American forces moved guns down off the mountain tops surrounding the harbor down into the city of Unalaska and into harbor facilities. This was partially as a deception and partially to defend against an expected land invasion. Civilian contractors filled sandbags to protect the new gun positions. On June 4, the Japanese launched a second attack on Dutch Harbor, which included nine fighters, 11 dive bombers, and six level bombers. Targets during the attack included some grounded aircraft, an army barracks, oil storage tanks, aircraft hangar, and a few merchant ships in the port. One wing of the military hospital at the base was destroyed. After hitting the fuel tanks, the bombers concentrated on the ships in the harbor, particularly the U.S. Army hospital ship USAHS Fillmore and the destroyer USS Gillis. During intense anti-aircraft fire, the Japanese succeeded in destroying the steamship Northwestern which, because of its large size, was mistakenly believed to be a warship. During the battle, an American anti-aircraft gun was blown up, resulting in four U.S. Navy deaths. Two Japanese dive bombers and one fighter, damaged by anti-aircraft fire, failed to return to their carriers. On the way back, the Japanese planes encountered an air patrol of six Curtiss P-40 fighters over Otter Point. A short aerial battle ensued which resulted in the loss of one Japanese fighter and two more dive bombers. Two out of the six U.S. fighters were lost as well.[68][69] During the attack, 43 Americans were killed and 50 others were injured.[70] One Japanese Zero was damaged by ground fire and crash-landed on Akutan Island. Although the pilot was killed, the plane was not seriously damaged. This Zero—known as the "Akutan Zero"—was recovered by American forces, inspected, and repaired. The recovery was an important technical intelligence gain for the U.S., as it showed the strengths and weaknesses of the Zero's design.[71]

Japanese invasion and occupation of Kiska

On June 6, 1942, the Empire of Japan launched an invasion of the island of Kiska in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, a territory of the United States.[72] Initially, the only American military presence on Kiska was a 12-man United States Navy weather station—two of whom were not present during the invasion—and a dog named Explosion. Over 500 soliders of the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces stormed the island and weather station, killing two Americans and capturing seven others. After realizing that Chief Petty Officer William C. House had escaped, a search was launched by the occupying forces. The search ended in vain, with House surrendering some 50 days after the initial seizure of the weather station, having been unable to cope with the freezing conditions and starvation. After 50 days of eating only plants and worms, he weighed just 80 pounds.[73] Between June 1942–July 1943, the Japanese occupied the island, using it as a forward military base. During the occupation, between 5,183–5,400 Japanese civilians and Japanese soldiers occupied the island and newly established military base.[74] After learning of the Japanese invasion of Kiska, American and Allied forces waged a continuous air bombardment campaign against the Japanese forces on Kiska. Also, US Navy warships blockaded and periodically bombarded the island. Several Japanese warships, transport ships, and submarines attempting to travel to Kiska or Attu were sunk or damaged by the blockading forces.

On July 29, 1943, the Imperial Japanese Navy, under the command of Rear Admiral Kimura Masatomi, who commanded two light cruisers and ten destroyers, slipped through the American blockade under the cover of fog, and successfully evacuated the island of Kiska, fearing an American invasion, which subsequently ended the Japanese presence in the Aleutian Islands. Not completely sure that the Japanese were gone, the Americans and Canadians executed an unopposed landing on Kiska on August 15, securing the island and ending the Aleutian Islands campaign. After the landing, the soldiers were greeted by a group of dogs which had been left behind. Among them was Explosion, who had been cared for by the Japanese. Even though the island was unoccupied, the Allied forces still suffered casualties. There was a thick fog which was in part responsible for friendly fire incidents, which killed 24 soldiers. Four more were killed by booby traps the Japanese had left behind. The destroyer USS Abner Read also struck a naval mine which killed 71.[75]

Japanese invasion and occupation of Attu

On June 7, 1942, Empire of Japan launched an invasion of the island of Attu in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, a territory of the United States. This invasion came one day after the capture of the nearby island of Kiska. During the day Japanese naval forces under the command of Admiral Boshirō Hosogaya landed troops without resistance on Attu. Then, 1,140 troops under the command of Major Matsutoshi Hosumi took control of the island and captured Attu's population, which consisted of 45 Aleuts and two white Americans, Charles Foster Jones, an amateur radio operator and weather reporter, originally from St. Paris, Ohio, and his wife Etta, a teacher and nurse, originally from Vineland, New Jersey.[76] The village consisted of several houses around Chichagof Harbor on the northeast side of the island. The 42 Aleut inhabitants who survived the Japanese invasion were taken to a prison camp, where sixteen of them would die while imprisoned. Charles Jones was killed by the Japanese forces immediately after the invasion because he refused to fix the radio that he destroyed to prevent the occupying troops from using it. His wife was subsequently taken prisoner as well. After landing, the soldiers began constructing an airbase and fortifications. Throughout the occupation, which lasted from June 1942–May 1943, American air and naval forces bombarded the island. Initially the Japanese intended to hold the Aleutians only until the winter of 1942; however, the occupation continued into 1943 in order to deny the Americans use of the islands. In August 1942, the garrison at Attu was moved to Kiska to help repel a suspected American attack. From August to October 1942, Attu was unoccupied until a 2,900-man force under Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki arrived. The new garrison continued constructing the airfield and fortifications.

On May 11, 1943, Major General Albert E. Brown's 7th U.S. Infantry Division made amphibious landings on Attu to retake the island. On May 12, I-31 was forced to surface five miles northeast of Chichagof Harbor, she was then sunk in a surface engagement with USS Edwards. Allied forces under General John L. DeWitt retook control of the island on May 30, 1943 after the remaining Japanese troops conducted a massive banzai charge. During the battle, 549 Americans were killed and 1,148 were wounded, with another 2,100 evacuated because of weather-related injuries. During the battle all but 29 men of the Japanese garrison were killed.[77]

Bombardment of Fort Stevens, Oregon

On June 21, 1942, the Imperial Japanese submarine I-25 fired on Fort Stevens, an American military base which defended the Oregon side of the Columbia River's Pacific entrance. The IJN submarine I-25 had been assigned to sink enemy shipping and attack the enemy on land with its 14 cm deck gun. On June 21, the I-25 had entered U.S. coastal waters, following fishing boats to avoid the mine fields in the area. During the evening, Tagami ordered his crew to surface his submarine at the mouth of the Columbia River, to target Fort Stevens, which was armed with Endicott era artillery, including 12 in (305 mm) mortars and several 10 in (254 mm) and 6 in (152 mm) disappearing guns. Once the submarine surfaced, Tagami ordered the deck gun crew to open fire on Fort Stevens. During the bombardment, the IJN I-25 fired a total of seventeen explosive shells towards Fort Stevens, causing no damage to the fort except one shell which damaged several telephone lines, in part because the fort's commander ordered an immediate blackout. The commander also refused to permit his men to return fire, which would have revealed their position. United States Army Air Forces planes on a training mission spotted the IJN I-25 and called in her location for an A-29 Hudson bomber to attack. The bomber found the target, but the IJN I-25 successfully dodged the falling bombs and submerged undamaged.[78][61]

Lookout Air Raids

On September 9, 1942, a Japanese Yokosuka E14Y Glen floatplane dropped two incendiary bombs with the intention of starting a forest fire. However, with the efforts of a patrol of fire lookouts and weather conditions not amenable to a fire, the damage done by the attack was minor. During the morning of September 9, the Japanese submarine I-25, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Akiji Tagami, surfaced west of Cape Blanco. The submarine launched a "Glen" Yokosuka E14Y floatplane, flown by Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita and Petty Officer Okuda Shoji, with a load of two incendiary bombs of 76 kilograms (168 lb) each. Howard "Razz" Gardner spotted and reported the incoming "Glen" from his fire lookout tower on Mount Emily in the Siskiyou National Forest. Although Razz did not see the bombing, he saw the smoke plume and reported the fire to the dispatch office. He was instructed to hike to the fire to see what suppression he could do. Dispatch also sent USFS Fire Lookout Keith V. Johnson from the nearby Bear Wallow Lookout Tower. Fujita dropped two bombs, one on Wheeler Ridge on Mount Emily in Oregon, which created a 1-foot deep crater. The location of the other bomb is unknown. The Wheeler Ridge bomb started a small fire 16 km (9.9 mi) due east of Brookings. The two men proceeded to the location and were able to keep the fire under control. Only a few small, scattered fires were started because the bombs were not dropped from the correct height. The men stayed on scene and worked through the night keeping the fires contained. In the morning, a fire crew arrived to help. A recent rainstorm had kept the area wet, which helped the fire lookouts contain the blaze. According to the Japanese records, both bombs were dropped, however, no trace has yet been found of the second bomb. On September 29, 1942, Fujita and his observer made a second bombing run, causing only negligible damage.[79][80]

Japanese bombing of Bly, Oregon

On May 5, 1945, a Japanese Fu-Go balloon bomb, which consisted of a hydrogen-filled paper balloon 33 feet (10 m) in diameter, with a payload of four 11-pound (5.0 kg) incendiary devices and one 33-pound (15 kg) high-explosive anti-personnel bomb, was discovered in the Fremont National Forest near the town of Bly, Oregon. Reverend Archie Mitchell and his pregnant wife Elsie (age 26) drove up Gearhart Mountain that day with five of their Sunday school students for a picnic. While Archie was parking the car, Elsie and the children discovered a balloon and carriage, loaded with an anti-personnel bomb, on the ground. A large explosion occurred; the four boys (Edward Engen, 13; Jay Gifford, 13; Dick Patzke, 14; and Sherman Shoemaker, 11) were killed instantly, while Elsie and Joan Patzke (13) died from their wounds shortly afterwards. An Army investigation concluded that the bomb had likely been kicked or dropped, and that it had lain undisturbed for about one month before the incident. Between November 1944 and April 1945, the Imperial Japanese Army launched about 9,300 balloons from sites on coastal Honshu, of which about 300 were found or observed in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The balloon near Bly, Oregon marked the only fatalities in the contiguous United States during all of World War II. The Fu-Go balloon bomb was the first weapon system with intercontinental range, predating the intercontinental ballistic missile.[81][82][83][84]

References

- ^ "MEXICANS DISTRUST US.; Incident at Agua Prieta Makes the International Situation Serious". The New York Times. 40 (19, 439). April 15, 1911. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ Hayostek, Cindy (2009). Douglas. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7065-5.

- ^ McLynn, Frank (2000). Villa and Zapata: A Biography of the Mexican Revolution. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9780224050517.

- ^ Bacinsk, Anthony. "Bordertown Blitz: Agua Prieta, Sonora/Douglas, Arizona, 1911" (PDF). Border Hub|Centro Fronterizo. University of Arizona. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ Harris, Charles H.; Louis R. Sadler (2007). The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution: The Bloodiest Decade, 1910–1920. The Internet Archive. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3484-8.

- ^ Investigation of Mexican Affairs. Hearing before a subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate. The Internet Archive. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1919.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Musicant, Ivan (August 1990). The Banana Wars: A History of United States Military Intervention in Latin America from the Spanish–American War to the Invasion of Panama. New York City: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-02-588210-2.

- ^ Clark, George B. (March 6, 2001). With the Old Corps in Nicaragua. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. p. 12.

- ^ "The Cushing was Hit by Airman's Bomb; Van Dyke Reports Attack on American Ship – To Make Representation to Germany". The New York Times. 64 (20, 917). Washington, D.C. May 2, 1915. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Falaba, Cushing, Gulflight". The New York Times Current History of the European War. 2 (3). University of California Press: 433–436. 1915. JSTOR 45322198. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Ramsay, David (2001). Lusitania, Saga and Myth. London: Chatham publishing. ISBN 1-86176-170-8.

- ^ Newspaper report including personal account of the first officer "Gulflight attack as officially told". The New York Times. May 15, 1915. p. 4. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- ^ Simpson, Colin (1972). Lusitania. Book club associates.

- ^ "Today in history: German submarine fires on SS Gulflight". The Gaston Gazette. Gastonia, North Carolina: Associated Press. May 1, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ "Lusitania Sunk by a Submarine, Probably 1,260 Dead". The New York Times. May 8, 1915. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Blackwood, Alan W. (April 3, 2015). "RMS Lusitania: It Wasn't & it Didn't". The Mariner's Mirror. 101 (2). Society for Nautical Research: 242–243. doi:10.1080/00253359.2015.1025522. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ Doyle, E. (2017). The Lusitania Tragedy: Crime or Conspiracy?. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 9781315099088.

- ^ Moore, Cameron (2022). "RMS Lusitania". Maritime Operations Law in Practice. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 151–167. doi:10.4324/9781003307013-17. ISBN 9781003307013.

- ^ Neiberg, Michael (September 2, 2015). "Dark Invasion, 1915: Germany's secret war and the hunt for the first terrorist cell in America". First World War Studies. 6 (3): 294–295. doi:10.1080/19475020.2015.1124537. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Thompson, Helen (July 8, 2015). "In 1915 a Former Harvard Professor Tried to Blow Up the U.S. Capitol". Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ "Bomb Rocks Capitol". United States Senate. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ "Black Tom 1916 Bombing". Famous Cases and Criminals. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney. "The Attacks on U. S. Shipping that Precipitated American Entry into World War I"(PDF). Northern Mariner Vol 17. p. 61.

- ^ Doenecke, Justus D. (2011). Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry Into World War I. Studies in Conflict, Diplomacy and Peace Series. University Press of Kentucky. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-8131-3002-6.

- ^ "Santa Maria". Uboat.net. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Scuba Diving – New Jersey & Long Island New York – dive Wreck Valley – Dive Sites – "Black Sunday" Shipwrecks – Victims of U-151". njscuba.net. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/germansubmarinea00unitrich#page/38/mode/2up German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic coast of the United States and Canada, Office of Naval Records and Library: Historical Section, Washington Government Printing Office, 1920. (pp. 36–38)

- ^ Hodos, Paul N. (2018). The Kaiser's lost Kreuzer: a history of U-156 and Germany's long-range submarine campaign against North America, 1918. Jefferson (N. J.): McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-7162-8.

- ^ Larzelere, Alex R. (2003). The Coast Guard in World War I: an untold story. Annapolis, Md: Naval Inst. Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-476-0.

- ^ Biggers, W. Watts (1985). "The Germans are Coming! The Germans are Coming!". Proceedings. 111 (6). United States Naval Institute: 38–43.

- ^ Larzelere, Alex (2003). Coast Guard in World War One. Naval Institute Press, p. 135. ISBN 1-55750-476-8

- ^ Smyser, Craig (1983). "The Columbus Raid". Southwest Review. 68 (1). Southern Methodist University: 78–84. JSTOR 43469529. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ "Francisco "Pancho" Villa's attack on Columbus". Historic Village Of Columbus. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ Harris, Larry A. (2013). Pancho Villa and the Columbus Raid. Literary Licensing, LLC. pp. 1–104. ISBN 9781494004989.

- ^ Zirinsky, Michael (August 1986). "Blood, Power, and Hypocrisy: The Murder of Robert Imbrie and American Relations with Pahlavi Iran, 1924". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 18 (3). Cambridge University Press: 275–292. doi:10.1017/S0020743800030488. S2CID 145403501. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ Price, Ethel Jackson (2003). Sierra Vista: Young City with a Past. Arcadia. ISBN 0738524344.

- ^ Ellis, Dolan; Sam Lowe (2014). Arizona Lens, Lyrics and Lore. Inkwell Productions. ISBN 978-1939625601.

- ^ "Border Reporter: 'The Bombing of Naco' by Michel Marizco (2011-09-11)". Border Reporter. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "The deadliest disaster to ever happen in each state". MSN. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Robertson, Albert. "Attacks on American Soil: Pearl Harbor and September 11". Digital Public Library of America. DPLA.

- ^ "1941: December 7: Japanese Attack on Midway Island". National Museum of the United States Navy. United States Navy. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Haskew, Michael E. (December 2021). "Epic Stand at Midway". Warfare History Network. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Young, Donald J. (March 30, 2015). The Fall of the Philippines: The Desperate Struggle Against the Japanese Invasion, 1941–1942. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0786498208.

- ^ Agdamag Jr., Jose Villanueva; Agdamag, Vicente Mendoza (January 1, 2003). 150 Days of Hell (Japanese Invasion of the Philippines 8 Dec 1941 – 6 May 1942). Makati: FRVN Business House. ISBN 978-9719320005.

- ^ Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area – Reports of General MacArthur Volume II Archived May 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, p. 104.

- ^ "War in the Pacific: The First Year", https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extContent/wapa/guides/first/sec2.htm. Retrieved May 4, 2016

- ^ "American Prisoners of War in the Philippines," Office of the Provost Marshal, November 19, 1945, http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/philippines/pows_in_pi-OPMG_report.html. Retrieved May 4, 2016

- ^ "War in the Pacific NHP: Liberation – Guam Remembers". nps.gov. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ "Seizure of Guam". National Park Service. October 24, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Chronology of the Dutch East Indies, December 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015.

- ^ Mansell, Roger (1999–2000). "The death of Private Kauffman, USMC Sumay Barracks, Guam Island, December 10th, 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 194–1942. Archived from the original on April 11, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ War in the Pacific: Outbreak of the War Archived May 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alford, Bob; Laurier, Jim (February 23, 2017). Darwin 1942: The Japanese Attack on Australia. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472816887.

- ^ Bowden, Brett (February 2016). "The Bombing of Darwin". Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy. 4 (1). University of Western Sydney. doi:10.18080/jtde.v4n1.44.

- ^ a b Grose, Peter (2009). An Awkward Truth: The Bombing of Darwin, February 1942 (paperback ed.). Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-607-3.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark (2001), p. 204

- ^ Lewis, Tom; Ingman, Peter (2013). Carrier Attack. Darwin 1942 : the complete guide to Australia's own Pearl Harbor. Avonmore Books: Avonmore Books. ISBN 978-0-9871519-3-3. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Lockwood, Douglas (November 2022). Australia Under Attack: The Bombing of Darwin 1942. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781742574042.

- ^ Hamilton, Nigel (2015). The Mantle of Command: FDR at War, 1941–1942. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 216. ISBN 978-0544227842.

- ^ "The Bombardment of Ellwood in 1942". Edhat. February 23, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Clark G. (1964). "Submarine Attacks on the Pacific Coast, 1942". Pacific Historical Review. 33 (2). American Historical Association: 183–193. doi:10.2307/3636595. JSTOR 3636595. Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ Andrews, Evan (August 30, 2018). "5 Attacks on U.S. Soil During World War II". HISTORY. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Leonard, Kevin Allen (2006). The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4047-4.

- ^ Messimer, Dwight R. (1983). Pawns of War: The Loss of the USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9780870215155.

- ^ Winkler, David F. (2024). America's First Aircraft Carrier: USS Langley and the Dawn of U.S. Naval Aviation (1st ed.). La Vergne: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781682475102.

- ^ https://www.naval-history.net/WW2UScasaaDB-USNBPbyDate1941-42.htm Archived 25 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 25 August 2023

- ^ Office of Naval Intelligence (March 1, 1945). "Chapter 1: The Attack on Dutch Harbor June 1942". Washington, D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on January 18, 2025.

- ^ "Dutch Harbor Bombing, June 1942". National Park Service. August 5, 2024.

- ^ National Park Service (June 7, 2017). "Fighting the Forgotten War: The Attack on Dutch Harbor" (Video). YouTube. United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Page 63/183

- ^ O'Leary, Michael. United States Naval Fighters of World War II in Action. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1980, pp 67–74. ISBN 0-7137-0956-1.

- ^ Funk, Caroline; Corbett, Debra; Harmsen, Hans; Goranson, Steve (2020). "Japan's World War II on Kiska Island: Previously Undocumented Features on the Vega Bay Coastline". Arctic Anthropology. 57 (2). University of Wisconsin Press: 149–166. doi:10.3368/aa.57.2.149. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ http://www.pacificwrecks.com/provinces/alaska_kiska [dead link]

- ^ PacificWrecks.com. "Pacific Wrecks". Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 3, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Mary Breu (2009) Last Letters from Attu, Alaska Northwest Books, ISBN 0882408100

- ^ Mitchell, Robert J.; Urwin, Gregory J. W.; Tyng, Sewell T.; Drummond Jr., Nelson L. (April 2000). The Capture of Attu: a World War II battle as told by the men who fought there. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803295575.

- ^ Gifford, Laura Jane (2015). "Shared Narratives: The Story of the 1942 Attack on Fort Stevens". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 116 (3). Oregon Historical Society: 376–383. doi:10.1353/ohq.2015.0007. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ Nobleman, Marc Tyler; Iwai, Melissa (2018). Thirty minutes over Oregon: a Japanese pilot's World War II story. Boston ; New York: Clarion Books and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-0544430761.

- ^ Hoff, Derek (1999). "Igniting Memory: Commemoration of the 1942 Japanese Bombing of Southern Oregon, 1962–1998". The Public Historian. 21 (2). National Council on Public History: 65–82. doi:10.2307/3379292. JSTOR 3379292. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ Uenuma, Francine (May 22, 2019). "In 1945, a Japanese Balloon Bomb Killed Six Americans, Five of Them Children, in Oregon". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ August, Melissa (May 5, 2023). "The Forgotten History of the Japanese Balloon Bomb That Killed Americans in World War II". TIME Magazine. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ Coen, Ross Allen (2014). Fu-go: the curious history of Japan's balloon bomb attack on America. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803249660.

- ^ Tanglen, Larry (2002). "Terror: Floated over Montana: Japanese World War II Balloon Bombs, 1944–1945". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 52 (4). Montana Historical Society: 76–79. JSTOR 4520467. Retrieved January 19, 2025.