Art Gallery of Ontario

Musée des beaux-arts de l'Ontario | |

| |

Dundas Street façade of the AGO in 2023 | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1900 |

|---|---|

| Location | 317 Dundas Street West Toronto, Ontario M5T 1G4 |

| Coordinates | 43°39′13″N 79°23′34″W / 43.65361°N 79.39278°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 321,664 (2021) 1st most visited nationally 93rd most-visited globally[1] |

| Director | Stephan Jost[2] |

| President | Robert J. Harding[3] |

| Curator | Julian Cox (Chief Curator) |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | ago |

The Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO; French: Musée des beaux-arts de l'Ontario) is an art museum in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located in the Grange Park neighbourhood of downtown Toronto, on Dundas Street West. The building complex takes up 45,000 square metres (480,000 sq ft) of physical space, making it one of the largest art museums in North America and the second-largest art museum in Toronto, after the Royal Ontario Museum. In addition to exhibition spaces, the museum also houses an artist-in-residence office and studio, dining facilities, event spaces, gift shop, library and archives, theatre and lecture hall, research centre, and a workshop.

It was established in 1900 as the Art Museum of Toronto and formally incorporated in 1903. The museum was renamed the Art Gallery of Toronto in 1919, before it adopted its present name, the Art Gallery of Ontario, in 1966. The museum acquired the Grange in 1911 and later undertook several expansions to the north and west of the structure. The first series of expansions occurred in 1918, 1924, and 1935, designed by Darling and Pearson. Since 1974, the gallery has undergone four major expansions and renovations. These expansions occurred in 1974 and 1977 by John C. Parkin, and 1993 by Barton Myers and KPMB Architects. From 2004 to 2008, the museum underwent another expansion by Frank Gehry. The museum complex saw further renovations in the 2010s by KPMB and Hariri Pontarini Architects.

The museum's permanent collection includes over 120,000 works spanning the first century to the present day.[4] The museum collection includes a number works from Canadian, First Nations, Inuit, African, European, and Oceanic artists. In addition to exhibits for its collection, the museum has organized and hosted many travelling art exhibitions.

History

The museum was founded in 1900 as the Art Museum of Toronto by a group of private citizens and members of the Toronto Society of Arts.[5][6] The institution's founders included George A. Cox, Lady Eaton, Sir Joseph W. Flavelle, J. W. L. Forster, E. F. B. Johnston, Sir William Mackenzie, Hart A. Massey, Professor James Mavor, F. Nicholls, Sir Edmund Osler, Sir Henry M. Pellatt, George Agnew Reid, Byron Edmund Walker, Mrs. H. D. Warren, E.R. Wood, and Frank P. Wood.[7]

The museum's incorporation was confirmed by the Government of Ontario three years later by legislation,[6] in An Act respecting the Art Museum of Toronto in 1903. The legislation provided the museum with expropriation powers in order to acquire land for the museum.[8] Before the museum moved into a permanent location, it held exhibitions in rented spaces belonging to the Toronto Public Library near the intersection of Brunswick Avenue and College Street.[9]

The museum acquired the property it presently occupies shortly after the death of Harriet Boulton Smith in 1909, when she bequeathed her historic 1817 Georgian manor, The Grange, to the gallery upon her death.[10][11] However, exhibitions continued to be held in the rented spaces at the Toronto Public Library branch until June 1913, when The Grange was formally opened as the art museum.[9] In 1911, ownership of The Grange, and the surrounding property was formally transferred to the museum.[12] Shortly afterwards, the museum signed an agreement with the municipal government of Toronto to maintain the grounds south of The Grange as a municipal park.[12]

In 1916, the museum drafted plans to construct a small portion of a new gallery building designed by Darling and Pearson in the Beaux-Arts style.[9] Excavation of the new facility began in 1916. The first galleries adjacent to The Grange were opened in 1918. In the next year, the museum was renamed the Art Gallery of Toronto, in an effort to avoid confusion with the Royal Ontario Museum, itself also an art museum.[13] In 1920, the museum also allowed the Ontario College of Art to construct a building on the grounds. The museum was expanded again in 1924, with the opening of the museum's sculpture court, its two adjacent galleries, and its main entrance on Dundas Street.[13] The museum was expanded again in 1935 with the construction of two additional galleries.[13] Portions of the 1935 expansions were financed by department store chain Eaton's.[12]

In 1965, the museum saw its collection of European and Canadian artworks expand, with the acquisition of 340 works from the Canadian National Exhibition.[14] During the mid-1960s, the director of the museum, William J. Withrow, pushed to have the museum designated as a provincial museum, in an effort to gain further provincial funding for the institution.[15] In 1966, the museum changed its name to the Art Gallery of Ontario, in order to reflect its new mandate to serve as the provincial art museum.[16]

In the 1970s, the museum embarked on another expansion of its gallery space,[13] with its first phase completed with the opening of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre on October 26, 1974. Although the museum planned on expanding its Canadian exhibits in its second phase of expansions, the creation of a centre dedicated to a non-Canadian artists drew criticism from Canadian Artists' Representation, and threatened to protest the opening of the centre.[17]

The museum was expanded again in 1993, which saw the 9,290.3 square metres (100,000 sq ft) of new space and 17,651.6 square metres (190,000 sq ft) of renovations—usable space, increasing the preexisting floorspace by 30 per cent. The expansion saw the renovation of 20 galleries and the construction of 30 galleries.[18] In 1978, the museum's staff was unionized under the Ontario Public Service Employees Union.[15]

During the 1990s, the museum drafted plans that would have seen the development of a pedestrian mall from University Avenue to the art gallery.[19] However, conflicting developments on adjacent properties, lack of support from the City of Toronto government, and the eventual development of another renovation plan by architect Frank Gehry saw the museum's plans for a pedestrian mall abandoned in the early 2000s.[19]

In 1996, Canadian multi-media artist Jubal Brown vandalized Raoul Dufy's Harbor at le Havre in the Art Gallery of Ontario by deliberately vomiting primary colours on it.[20]

Under the direction of then-CEO Matthew Teitelbaum, the museum embarked on a CA$254 million (later increased to CA$276 million) redevelopment plan by Frank Gehry in 2004, called Transformation AGO. Although Gehry was born in Toronto, the redevelopment of the museum complex would be his first work in Canada. The project initially drew some criticism. As an expansion, rather than a new creation, concerns were raised that the structure would not look like a Gehry signature building,[21] and that the opportunity to build an entirely new gallery, perhaps on Toronto's waterfront, was being squandered. During the course of the redevelopment planning, board member and patron Joey Tanenbaum temporarily resigned his position over concerns about donor recognition, design issues surrounding the new building, as well as the cost of the project. The public rift was subsequently healed.[22]

Kenneth Thomson was a major benefactor of Transformation AGO, donating much of his art collection to the gallery (providing large contributions to the European and Canadian collections), in addition to providing CA$50 million towards the renovation, as well as a CA$20 million endowment.[23] Thomson died in 2006, two years before the project was complete.

In 2015, the Canadian Jewish News reported 46 paintings and sculptures in the museum's possession held "a gap in provenance," with the history of their ownership from the years 1933 and 1945 having disappeared, coinciding with the Third Reich's existence.[24] The museum publishes spoliation research on its public website.[25]

In 2018, the museum formally changed the name of Emily Carr's 1929 The Indian Church painting to Church at Yuquot Village in an effort to remove culturally insensitive language from the title of works in its collection.[26] A note next to the painting provides the original name of the piece and explains Carr's use of the term was in keeping with "the language of her era".[26] The museum has also reviewed the titles of several other works on a case-by-case basis, as items from the Canadian collection are rotated from its exhibit, or from its storage.[27]

In May 2019, the museum revised its admission model, offering free entry to visitors 25 years of age and under and a CA$35 pass for all others, which provides admission to the museum for the entire year.[28]

The painting, Still Life with Flowers by Jan van Kessel the Elder, was restituted to the heirs of Dagobert and Martha David in 2020, after the museum confirmed the item's provenance and that the David family was forced to sell the item during the Second World War. Following its forced sale, the painting was resold to a Canadian, who later donated the piece to the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1995.[29][30][31]

Selected exhibitions since 1994

The Art Gallery of Ontario has hosted and organized a number of temporary and travelling exhibitions in its galleries. A select list of exhibitions since 1994 include:

- From Cézanne to Matisse: Great French Paintings from The Barnes Foundation (1994)

- The OH!Canada Project (1996)

- The Courtauld Collection (1998)

- Treasures from the Hermitage Museum, Russia: Rubens and His Age (2001)

- Voyage into Myth: French Painting from Gauguin to Matisse, from the Hermitage Museum (2002)

- Turner, Whistler, Monet: Impressionist Visions (2004)

- Catherine the Great: Arts for the Empire – Masterpieces from the Hermitage Museum, Russia (2005)

- Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon (2007)

- Drawing Attention: Selected Works on Paper from the Renaissance to Modernism (2009)

- King Tut: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs (2009)

- Rembrandt/Freud: Etchings from Life (2010)

- Julian Schnabel: Art and Film (2010)

- Maharaja: The Splendour of India's Royal Courts (2010)

- Drama and Desire: Artists and the Theatre (2010)

- At Work: Hesse, Goodwin, Martin (2010)

- The Shape of Anxiety: Henry Moore in the 1930s (2010)

- Black Ice: David Blackwood Prints of Newfoundland (2011)

- Abstract Expressionist New York (2011)

- Haute Culture: General Idea (2011)

- Chagall and the Russian Avant-Garde: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2011)

- Jack Chambers: Light, Spirit, Time, Place and Life (2012)

- Iain Baxter&: Works 1958–2011 (2012)

- Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée Picasso Paris (2012)

- Berenice Abbott: Photographs (2012)

- Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics and Painting (2012)

- Francis Bacon and Henry Moore: Terror and Beauty (2014)

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now's The Time (2015)

- J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free (2015)

- Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s (2016)

- The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris (2016)

- Theaster Gates: How to Build a House Museum (2016)

- Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures (2016)

- Mystical Landscapes: Masterpieces from Monet, Van Gogh and More (2016)

- Toronto: Tributes + Tributaries, 1971–1989 (2016)

- Every. Now. Then. Reframing Nationhood (2017)

- Rita Letendre: Fire & Light (2017)

- Free Black North (2017)

- Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters (2017)

- Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors (2018)

- Mitchell/ Riopelle: Nothing in Moderation (2018)

- Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak (2018)

- Mickalene Thomas: Femmes Noires (2018)

- Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental (2018)

- Anthropocene (2018)

- Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory (2019)

- Impressionism in the Age of Industry: Monet, Pissarro and more (2019)

- Brian Jungen Friendship Centre (2019)

- Early Rubens (2019)

- Hito Steyerl: This is the future (2019)

Museum complex

The museum's property was acquired in 1911 when The Grange and the surrounding property south of Dundas Street were bequeathed to the institution by Harriet Boulton Smith. The Grange manor was reopened to serve as the museum's building in 1913. Since its opening, the museum underwent several expansions to the north, and west of The Grange. Expansions to the museum were opened in 1918, 1926, 1935, 1974, 1977, 1993, and 2008.[9]

The museum complex takes up 45,000 square metres (480,000 sq ft) of physical space,[9] and is made up of two buildings, The Grange, and the main building expansion, built to the north, and west of The Grange. After the main building's redevelopment in 2008, the museum complex has 12,000 square metres (129,000 sq ft) of dedicated gallery space.[32]

In addition to the complex, the museum also owns the land directly south of The Grange, Grange Park. The land is maintained as a municipal park in perpetuity by the Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation Division, as a result of an agreement between the museum and the City of Toronto.[33][34]

The Grange

The Grange is a historic manor built in 1817 and is the oldest portion of the museum complex. The building is two-and-a-half storeys tall, and built from stone, brick-on-brick cladding, and wood and glass detailing.[12] Although it was designed in a Neoclassical style, it retains the symmetrical features of Georgian-styled buildings, found in Upper Canada before the War of 1812.[12] The building was initially used as a private residence, with its previous owners having altered the property several times before its re-purposing into an art museum. This includes the addition of a west wing in the 1840s and another wing to the west in 1885.[12] Although the museum expanded the complex in the decades after acquiring the property, The Grange itself saw little work done to it for the next half-century. As a part of its 1967–1973 expansion project, the museum restored The Grange to its 1830s configuration and repurposed the building into a historic house.[12] The Grange was operated as a historic house until it was later repurposed by the museum as an exhibition space and members' lounge.

The building was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1970.[9] The building was later designated by the City of Toronto government as "The Grange and Grange Park" in 1991 under the Ontario Heritage Act.[9] In 2005, the City of Toronto government, and the museum entered a heritage easement agreement,[9] which requires designated interior and exterior elements of The Grange to be retained for perpetuity.[35]

Main building

Situated directly north and west of The Grange, the main building was opened to the public in 1918 and has undergone several expansions and renovations since opening.[36] Plans for the "main building" to the north of The Grange originated in 1912 when the architectural firm Darling and Pearson submitted their expansion plans for the north of The Grange.[37] Due to The Grange's location, and historic value, the expansion plans were limited along the southern portions of the museum's property; as the museum wanted to preserve The Grange's southern façade and the municipal park south of the building.[36]

The expanded plan featured 30 viewing halls, all of which would surround one of three open courtyards, an English landscape garden, an Italian garden, and a sculpture courtyard.[36] The design was largely modelled after another building designed by Darling and Pearson, the Royal Ontario Museum.[36] The designs by Darling and Pearson were intended to be implemented in three phases, although the plans for the final design phase were abandoned by the mid-20th century.[36] Construction for the first phase began in 1916 and was completed in 1918.[9][36] The first phase featured an expansion wing adjacent to The Grange, that had three galleries.[36]

The second phase of the design was opened in 1926. It included half of the sculpture court (later named Walker Court) to the north of the 1918 wing, two additional galleries flanking the sculpture court, and an entrance to the north.[36] The exterior façade of the 1926 expansion was only made of bricks and stucco. No serious designs were planned for the exterior facade of the 1926 expansion, as the museum envisioned that the exterior facade would eventually be enclosed in stone by future expansions.[38] Further expansions to the east and the west of the building was completed in 1935.[38] However, as the third phase of expansion was never embarked on, the "temporary façade" to the north remained the same until the early 1990s.[38]

Late-20th century expansions

Another series of expansion was undertaken by the museum during the 1970s, as a part of a new three-phased expansion plan; with its first two phases designed by John C. Parkin.[38] The first phase of the expansion was completed in 1974, which saw the restoration of the Grange, and the opening of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre,[38] a centre which Moore helped design.[17] Moore choose the dimensions for the centre, the colour of the floor and the walls, and saw the installation of a skylight in the centre, in order to allow more natural light into the gallery.[17] The centre saw little alteration to its design during the museum's expansion in the early 2000s, with the exception of a 7-metre (23 ft) opening, providing access to the Galleria Italia.[39]

The second phase saw the opening of several new galleries adjacent to Beverley Street in 1977.[38] The third phase of expansion planned by the museum was delayed until August 1986, when it announced a competition for Ontario-based architects to design the museum's southwest, and northern extension on Dundas Street to cover the "temporary façade".[38] A seven-member panel eventually selected a design by Barton Myers.[19] The architectural firm KPMB Architects was contracted to complete the expansion, which opened in 1993.[38] The expansion in 1993 saw 9,290.3 square metres (100,000 sq ft) of new space built, and the construction of 30 new galleries.[18] After the expansion and renovations in 1993, the museum complex had approximately 38,400 square metres (413,000 sq ft) of interior space.[9]

2004–2008 redevelopment

From 2004 to 2008, the museum's building underwent a CA$276 million redevelopment, led by Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry. Gehry was commissioned to expand and revitalize the museum, not to design a new building; as such, one of the challenges he faced was to unite the disparate areas of the building that had become "a bit of a hodgepodge" after six previous expansions dating back to the 1920s.[40] The redevelopment plans was the first design by Gehry to not feature a highly contorted structural steel frame for the building's support system.[41]

The exterior fronting on Dundas Street was changed as a part of the redevelopment; with the front entrance moved to the north, aligning with Walker Court, and the installation of a 200-metre (660 ft) glass and wood projecting canopy known as the "Galleria Italia".[42] The roof of Walker's Court was also redeveloped, with steel truss girders installed, and glued laminated timber used to support the glass-panelled roof, which provides 325 square metres (3,500 sq ft) of skylight for the courtyard. The southern portion of the museum building also saw redevelopment, with the construction of a five-storey South Gallery block, and a protruding spiral staircase that connects the fourth and fifth levels of the block.[42] The exterior facade of the South Gallery Block includes glass and custom-made titanium panels, and like the Dundas Street fronting, is supported by glued laminated timber.[42] The new addition required the demolition of the postmodernist wing by Myers and KPMB Architects.

Wood was used extensively during the redevelopment, with woodwork needing to be done for the museum's hardwood floor, information kiosk, ticket booth, security booth, and the stairs inside the building, including a spiral staircase in Walker Court.[42] The facings of the booths, staircases, and the hardwood floor is made from Douglas fir wood.[43]

The redeveloped building opened in November 2008, with the transformation increasing the museum's total floor area by 20 per cent for a total of 45,000 square metres (480,000 sq ft); as well as increasing the art viewing space by 47 per cent.[41][9] An event space called Baillie Court occupies the entirety of the third floor of the south tower block.

Galleria Italia

The Galleria Italia is a 200 metres (660 ft) glass, steel, and wood projecting canopy at the fronting of Dundas Street, also acting as a viewing hall on the second level of the building. The galleria was named in recognition of a $13 million contribution by 26 Italian-Canadian families of Toronto, a funding consortium led by Tony Gagliano, a past President of the museum's Board of Trustees.

Both ends of the glass and wood canopy extend past the building forming "tears", providing the appearance that the building's façade has been pulled off the building. The Galleria Italia is made out of 200 metres (660 ft) glued laminated timber and glass gallery space atop the Dundas Street walkway.[42] Approximately 1,800 glued laminated timber pieces were used on the facade of the Galleria Italia; and 2,500 timber connectors.[44]

The galleria is composed of two layers, with the inner layer formed by 47 vertical radial arches, each of which increases in spacing between one another as it approaches the main entrance.[44] The radials provide lateral support against the wind for the outer layer, a glued laminated timber mullion grid, as it transfers the weight to the floor. Both of these sit on a steel frame, which supports the galleria.[44] The mullion grid itself is attached to sliding bearings that allow its curtain wall to adjust to changes in temperature, without compromising the integrity of the wood.[44] Most of the timber was made of Douglas fir trees, from a manufacturer based in Penticton, British Columbia.[43] Each piece of timber is unique, given that the galleria's design featured slants that increased in width incrementally, and whose curvatures were changing throughout its length.[45]

The galleria uses 128 steel horizontal beams to prevent the radials from contorting.[45] Given that the museum is typically maintained at 50 per cent relative humidity, the steel used to support the glued laminated timber required a galvanized finish to prevent corrosion.[41]

Reception for 2000s redevelopment

The completed expansion received wide acclaim, notably for the restraint of its design. An editorial in The Globe and Mail called it a "restrained masterpiece", noting: "The proof of Mr. Gehry's genius lies in his deft adaptation to unusual circumstances. By his standards, it was to be done on the cheap, for a mere $276 million. The museum's administrators and neighbours were adamant that the architect, who is used to being handed whole city blocks for over-the-top titanium confections, produce a lower-key design, sensitive to its context and the gallery's long history."[46] The Toronto Star's Christopher Hume called it "the easiest, most effortless and relaxed architectural masterpiece this city has seen".[47]

Critics also noted Gehry's ability to reinvigorate older structures, with The Washington Post commenting "Gehry's real accomplishment in Toronto is the reprogramming of a complicated amalgam of old spaces. That's not sexy, like titanium curves, but it's essential to the project."[21] The architecture critic of The New York Times wrote: "Rather than a tumultuous creation, this may be one of Mr. Gehry's most gentle and self-possessed designs. It is not a perfect building, yet its billowing glass facade, which evokes a crystal ship drifting through the city, is a masterly example of how to breathe life into a staid old structure. And its interiors underscore one of the most underrated dimensions of Mr. Gehry's immense talent: a supple feel for context and an ability to balance exuberance with delicious moments of restraint. Instead of tearing apart the old museum, Mr. Gehry carefully threaded new ramps, walkways and stairs through the original."[48]

2010s and 2020s renovations and expansions

The museum opened the Weston Family Learning Centre in October 2011, designed by Hariri Pontarini Architects. The 3,252-square-metre (35,000 sq ft) space is an exploration art centre, featuring a hands-on centre for children, a youth centre, and an art workshop and studio.[49] Several months later, in April 2012, the museum opened the David Milne Study Centre, which was designed by KPMB Architects.[50][51][52] The cost to build the David Milne Study Centre cost the museum approximately C$1 million.[53] The South Entrance and lounge outside the library, also designed by Hariri Pontarini Architects, was opened in July 2017.[54] The renovated and renamed J. S. McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art[55] opened in July 2018.

In 2022, Selldorf Architects, Diamond Schmitt Architects and Two Row Architects were contracted by the museum to design a new gallery space for contemporary art.[56][57] The proposed expansion, later named the Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, would add 3,700 square metres (40,000 sq ft) to the building, and would be the building's seventh major expansion.[58]

Permanent collection

AGO's permanent collection saw significant growth in the late 20th and early 21st century. The museum's permanent collection grew from 3,400 works in 1960 to 10,700 in 1985.[15] As of March 2021, the AGO's permanent collection holds over 120,000 pieces, representing many artistic movements and eras of art history.[4] The museum's collection is organized into several "collection areas," which typically encompass works from a specific art form, artist, benefactor, chronological era, or geographic locale. Until the early 1980s, works collected for the museum's collection were primarily Canadian or European artists.[59] Its collection has since expanded to include artworks from the Indigenous peoples in Canada, and other cultures from around the world.

The museum's African collection includes 95 artworks, most of which originate from the 19th century Sahara.[60] Exhibited at a permanent gallery on the second floor of the museum,[60] most of the pieces in the African collection were gifted to the museum by Murray Frum, with the first pieces donated to the museum in 1972.[61] The museum also has several Ethiopian Orthodox manuscripts and artworks, although these works form a part Thomson Collection of boxwoods and ivories.[62]

In 2002, the museum was bequeathed 1,000 works by Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islanders artists.[63] Some of these items are exhibited at a gallery on the second floor of the museum. In 2004, Kenneth Thomson donated over 2,000 works from his collection to the museum.[64] Although the majority of the Thomson collection is made up of works by Canadian or European artists, the collection also includes works created by artists in other parts of the world.

Canadian

The museum includes an extensive collection of Canadian art, from pre-Confederation to the 1990s.[65] Most of the museum's Canadian art is exhibited on the second floor, with 39 viewing halls dedicated to exhibiting 1,447 pieces from the museum's Canadian collection.[66] The wing includes the 23 viewing halls of the Thomson Collection of Canadian Art, and the 14 viewing halls of J.S. Mclean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art.[67] Canadian works are also exhibited in the David Milne Centre and the visible storage area in the museum's concourse.

The galleries of the Thomson Collection of Canadian Art provide an in-depth look at the works of individual artists, whereas the other viewing halls of organized around later thematic issues.[67] The Thomson Collection was donated to the museum by Kenneth Thomson in January 2004.[68] The collections features nearly 650 paintings and works by Canadian artists; 250 of which were created by Tom Thomson;[68] 145 works by Cornelius Krieghoff;[64] 168 works by David Milne,[53] and others by the Group of Seven. Nearly two-thirds of the collection was re-framed in preparation for their installation into the viewing halls.[68]

In addition to the Thomson Collection of Canadian Art, works by David Milne are also housed in the David Milne Study Centre.[53] The centre was opened in 2012, and features computer terminals linked to the Milne Digital Archives and televisions which play films on Milne's life.[53] The centre houses works and 230 other artifacts belonging to Milne, including diaries, journal, and paint boxes. Most of the Milne artifacts were gifted to the museum by Milne's son in 2009.[53]

The J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art exhibits 132 from Canadian and indigenous artists.[69] Approximately 40 percent of works presented in the centre were created by Indigenous artists.[69] The McLean Centre for Indigenous and Canadian Art is 1,200 square metres (13,000 sq ft),[70] with 14 viewing halls.[67] Three of these galleries are dedicated to exhibiting Inuit art, whereas one is dedicated to exhibiting contemporary First Nations art.[70]

Works in the Mclean Centre are organized around larger thematic issues relating to Canadian history, as opposed to chronologically.[67][71] As a result, works from indigenous and Canadian artists are presented together to showcase the reciprocal influences and conflict between the two.[69] An example of such thematic presentation is evident in how the museum exhibits Tom Thomson's The West Wind. When the painting was exhibited at the Mclean Centre, it was presented with Anishinaabe pouches adjacent to it, showcasing how two peoples viewed northern Ontario at that time.[72] Text that accompanies works in the centre are presented in three languages, English, French, and either Anishinaabemowin or Inuktitut.[69] The walls along the primary entry point into the McLean Centre are marked by small projectile points from arrows, spears, and knives from 9,000 BCE to 1,000 CE. The projectiles form a part of an art installation instead of an ethnographic or archeological display.[73]

Landscape paintings from Canadian artists were among the first to be acquired for the museum's collection.[14] The museum's Canadian collection has works from several Canadian artists, including Jack Bush, Paul-Émile Borduas, Kazuo Nakamura, and members of the Group of Seven.[65] The museum has more than 300 works by David Milne; 168 of which were donated to the museum as a part of the Thomson Collection of Canadian Art.[53] The museum also has nearly 150 works from A. Y. Jackson, although most of it is in storage.[74] The collection also features works from Canadian sculptors Frances Loring, Esmaa Mohamoud,[75] and Florence Wyle.[65]

The museum also has a large collection of Inuit artworks. The 1970s saw the first Inuit artwork added to the museum's collection; with the Art Gallery of Ontario acquiring the Sarick Collection, the Isaacs Reference Collection, and the Klamer Collection during the 1970s and early 1980s.[14] In 1988, the museum formed the Inuit Collections Committee to maintain and grow the collection.[14] The collection includes 2,800 sculptures, 1,300 prints, 700 drawings and wall hangings from Inuit artists.[63] 500 of these works are exhibited at the Inuit Visible Storage Gallery,[76] opened in 2013.[77]

Conversely, the museum did not acquire its first First Nations artwork until 1979, acquiring a piece by Norval Morrisseau for its contemporary collection.[14] The Art Gallery of Ontario did not acquire First Nations art until the late 1970s, to prevent overlap between the AGO's permanent collection and the permanent collections of the Royal Ontario Museum, which already had a collection of First Nations art.[14] The early 21st century saw the museum increase the representation of First Nations art in its Canadian-centred galleries, including the R. Samuel McLaughlin Gallery.[78] First Nations artists whose works are featured in the museum's collection include Charles Edenshaw and Shelley Niro.[63]

Contemporary

The museum's contemporary art collection contains works from international artists from the 1960s to the present and Canadians from the 1990s to the present.[79] The collection also extends to installations, photography, graphic art (such as concert, film, and historic posters), film and video art, and even minimal music. Works from these collections are exhibited in several centres and galleries throughout the museum, including the Vivian & David Campbell Centre for Contemporary Art, which comprise the upper three levels of the south gallery block, and the Galleria Italia.

The museum's contemporary collection includes several works by Canadian artists, General Idea, Brian Jungen, Liz Magor, Michael Snow, and Jeff Wall.[79] The museum's contemporary collection also has works by international artists in the Arte Povera, conceptualism minimalism, neo-expressionism, pop art, and postminimalism movements.[79] Artists from these movements whose works are included in the museum's collection include Jim Dine, Donald Judd, Mona Hatoum, Pierre Huyghe, John McCracken, Claes Oldenburg, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Gerhard Richter, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, Andy Warhol, and Lawrence Weiner.[79]

The museum also features a permanent exhibition of Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Mirror Room – Let's Survive Forever in one of the viewing halls of the Signy Eaton Gallery.[80] The permanent Infinity Room was purchased in 2018 for C$2 million and opened in May 2019 due to popular demand, after the success of a larger multi-room Kusama and Infinity Mirror Room travelling exhibit held in the same year.[80]

European

The museum has a large collection of European art ranging from 1000 CE to 1900 CE,[81] Items from the museum's European collection are exhibited in several viewing halls throughout the museum. The Tannenbaum Centre for European Art and its viewing halls are located on the ground floor. Paintings and sculptures from the Thomson Collection of European Art are exhibited on the ground floor, while the ship models from the Thomson collection are exhibited in the museum's concourse.

The European Collection includes the Margaret and Ian Ross Collection, which features several bronze sculptures and medals, with a particular emphasis on Baroque art from Italy.[81] The museum's collection of European paintings and sculptures was further bolstered in January 2004, after the museum acquired the Thomson Collection of European Art.[68] The Thomson Collection of European Art includes over 900 objects, including 130 ship models.[64]

The Thomson Collection of European Art includes the world's largest holding of the Gothic boxwood miniatures, featuring 10 carved beads and two altarpieces.[82][83] Other works featured in the Thomson Collection for European Art includes Massacre of the Innocents by Peter Paul Rubens.[84] The painting was acquired by Ken Thomson in 2002 for C$115 million,[84] at the time the most expensive Old Master work sold at an art auction.[85][note 1] Thomson intended for the work to serve as the centrepiece for the collections he donated to the museum in 2004.[84] When the museum reopened in 2008, the painting was installed in a blood-red, low-lit room in the Thomson Collection for European Art.[84] The room featured no other paintings, with the only lighting in the room directed towards the work.[84] The painting remained at that location until 2017 when it was placed in a gallery with other works from the European collection.[84]

In 2019, the museum acquired the painting Iris Bleus, Jardin du Petit Gennevilliers by Gustave Caillebotte for more than C$1 million.[86] The painting is the second work by Caillebotte to enter the permanent collections of a Canadian art museum.[86] The museum's European collection also includes major works by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Giovanni del Biondo, Edgar Degas, Thomas Gainsborough, Paul Gauguin, Frans Hals, Claude Monet, Angelo Piò, Nino Pisano, Rembrandt, Auguste Rodin, and James Tissot.[81]

Modern

The museum's modern art collection includes works from Americans, and Europeans from the 1900s to the 1960s,[87] Works by Canadian artists during that period are typically exhibited as a part of its Canadian collection, as opposed to the museum's modern art collection. Works from the modern art collection are exhibited in several centres and galleries throughout the museum, including the Joey & Toby Tanenbaum Sculpture Atrium, the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre, and several other galleries on the ground floor of the museum.

The museum is home to the largest public collection of works by Henry Moore, most of which is held in the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre.[88] The museum dedicated approximately 3,000 square metres (32,000 sq ft) of space to the sculptor, which includes the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre, and related galleries including the Irina Moore Gallery.[89] Moore donated 300 pieces,[15] nearly his entire personal collection, to the museum in 1974.[87] The donation originated from a commitment made by Moore on December 9, 1968, to donate a significant portion of his work to the Art Gallery of Ontario, contingent that the museum builds a dedicated gallery to exhibit his works.[90] In addition to the works donated by Moore, the museum also purchased another piece, Two Large Forms, from the sculptor in 1973.[17] The sculpture was originally placed at the museum's northeast façade, near the intersection of Dundas and McCaul streets.[17] However, the museum later relocated the sculpture to Grange Park nearby in 2017 as part of the park's renovation.

The museum's modern collection also includes works by Pierre Bonnard, Constantin Brâncuși, Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Jean Dubuffet, Jacob Epstein, Helen Frankenthaler, Alberto Giacometti, Natalia Goncharova, Arshile Gorky, Barbara Hepworth, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Amedeo Modigliani, Claude Monet, Ben Nicholson, Pablo Picasso, Gino Severini, and Yves Tanguy.[87]

Photography

In 2019, the Art Gallery of Ontario had a photography collection of 70,000 photographs dating from the 1840s to the present.[91] The photograph collection includes 495 photo albums from the First World War.[91] Items from this collection are exhibited in two viewing halls on the ground floor.

In 2017, the museum acquired 522 photographs by Diane Arbus, providing the museum with the largest collection of Arbus's photographs outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[92] In June 2019, the museum acquired the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photos, which includes 3,500 historic photographs of the Caribbean from the 1840s to 1940s.[93] The collection was acquired by the museum for $300,000, most if which was provided by 27 donors from Toronto's Caribbean community.[93] The Montgomery Collection is the largest collection of its kind outside the Caribbean.[93] Other photographers whose works are featured in the collection include Edward Burtynsky, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Robert J. Flaherty, Suzy Lake, Arnold Newman, Henryk Ross, Josef Sudek, Linnaeus Tripe, and Garry Winogrand.[91]

Prints and drawings

The museum's prints and drawings collection includes more than 20,000 prints, drawings, and other works on paper, from the 1400s to the present day. This collection usually is displayed little at a time with revolving exhibitions. However, the collection is viewable by appointment at the museum's Marvin Gelber Print and Drawing Study Centre.[94]

The collection includes the largest and most significant body of works from Betty Goodwin, with a bulk of the works given to the gallery by the artist.[95] In 2015, the museum was bequeathed 170 drawings, prints, and sculptures by Käthe Kollwitz.[96] The prints and drawings collection also includes drawings by David Blackwood, François Boucher, John Constable, Greg Curnoe, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Thomas Gainsborough, Paul Gauguin, Wassily Kandinsky, Michelangelo, David Milne, Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele, Michael Snow, Walter Trier, Vincent van Gogh, and Frederick Varley; and prints by Ernst Barlach, James Gillray, Francisco Goya, Käthe Kollwitz, Henry Moore, Robert Motherwell, Rembrandt, Thomas Rowlandson, Stanley Spencer, James Tissot, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and James McNeill Whistler.[94]

Library and archives

The Art Gallery of Ontario also houses the Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives. The library and archives are open to the public and require no entrance fee.[97] However, access to the museum's archives, and its special collections requires a scheduled appointment.[98] The library also serves as the adjunct art history library for OCAD University.[99]

Library

The general collections of the library reflect the permanent collection of works of art and the public programs of the Art Gallery of Ontario, containing over 300,000 volumes for general art information and academic research in the history of art.[98] The library serves as a reference library; materials in the collections do not circulate. Holdings encompass Western art in all media from the medieval period to the 21st century; the art of Canada's indigenous peoples including Inuit art; and African and Oceanian art.

The library additionally comprises Canadian, American and European art journals and newspapers; over 50,000 art sales and auction catalogues (late 18th century to current); 40,000 documentation files on Canadian art and artists, and international contemporary artists; and multimedia, digital and microform collections. Materials may be searched on the online catalogue.[100] The Library & Archives also produces pathfinders and bibliographies for collections research, such as the Thomson Collection Resource Guide to the large collection of works of art donated by benefactor and collector Kenneth Thomson.[101]

The library's rare books collection includes art historical sourcebooks from the 17th century to the present; British Neoclassical folios of the 18th century; catalogues raisonnés; British and Canadian illustrated books and magazines; travel guides, particularly Baedekers, Murrays, and Blue Guides; French art sales catalogues from the late 18th century to the mid-20th century; and artists' books.

Archives

The museum's archives document the history of the institution since its establishment in 1900, as well as The Grange since 1820. Series include exhibition files, publicity scrapbooks (documenting Gallery exhibitions and all other activity), architectural plans, photographs, records of the Gallery School, and correspondence (with art dealers, artists, collectors, and scholars). Because of the regularity with which artists' groups held exhibitions at the Gallery, the archives are a resource for research into the activities of the Group of Seven, the Canadian Group of Painters, the Ontario Society of Artists, and others.

The Art Gallery of Ontario's special collections are one of the most important concentrations of archival material on the visual arts in Canada. In over 150 individual fonds and collections, ranging in date from the early 19th century to the present day, the Special Collections document with primary source material artists, art dealers and collectors, artist-run galleries, and other people and organizations that have shaped the Canadian art world, as well as the Tom Thomson Catalogue Raisonné files.[102]

Programs

Artist-in-residence

AGO operates an artist-in-residence program, granting selected artists access to its facilities, a stipend covering materials and living costs, and a dedicated studio, the Anne Lind AiR Studio in the Weston Family Learning Centre.[103][104] Artists-in-residence are invited to create new work and ideas, and to use all media, including painting, drawing, photography, film, video, installation, architecture and sound.[105] The program is the first of its kind to be established at a major Canadian art gallery.[103]

Past artists-in-residences have included:

- Gauri Gill (September 2011)[106]

- Paul Butler (October–November 2011)[105][107][108][109]

- Margaux Williamson (January–March 2012)[103]

- Hiraki Sawa (April–July 2012)[110]

- Heather Goodchild (July–August 2012)[111]

- Mark Titchner (September–October 2012)[112]

- Jo Longhurst (November–December 2012)[113]

- Life of a Craphead (January–March 2013)[111]

- Jason Evans (April–May 2013)[111]

- Mohamed Bourouissa (June–August 2013)[111]

- Diane Borsato (September–November 2013)[111]

- Sara Angelucci (November 2013 – January 2014)[111]

- Jim Munroe (January–April 2014)[111]

- Ame Henderson (August – October 2014)[114]

- Greg Staats (October – December 2014)[111]

- Mammalian Diving Reflex (December 2014 – February 2015)[111]

- FAG Feminist Art Gallery (February–April 2015)[111]

- Meera Margaret Singh (June–August 2015)[111]

- Lisa Myers (September–November 2015)[111]

- Jérôme Havre (December–March 2016)[111]

- Public Studio (May–July 2016)[111]

- Walter Scott (September–November 2016)[111]

- Will Kwan (January–April 2017)[111]

- EMILIA-AMALIA (May – August 2017)[111]

- Tanya Lukin Linklater (August 2017)[111]

- Zun Lee (September 2017 – January 2018)[111]

- Sara Cwynar (February–April 2018)[111]

- Seika Boye and Sandra Brewster (August 2018 – February 2019)[111]

- Natalie Ferguson and Toby Gillies (February 4 – March 31, 2019)[111]

- Haegue Yang (July 14–28, 2019)[111]

- Ness Lee (October 29, 2019 - January 6, 2020)[111]

- Alicia Nauta (January 20 – March 30, 2020)[111]

- Alvin Luong (April 7 – September 10, 2021)[111]

- Nada El-Omari and Sonya Mwambu (June 3 – September 10, 2021)[111]

- Timothy Yanick Hunter (August 4 – September 30, 2021)[111]

- Eric Chengyang and Mariam Magsi (February 1 – April 26, 2022)[111]

- Ivetta Sunyoung Kang (April 25 – July 19, 2022)[111]

- Shion Skye Carter (July 18 – October 25, 2022)[111]

- Lauren Prousky (January 23 – April 18, 2023)[111]

- Eva Grant (April 19 – July 13, 2023)[111]

- Clayton Lee (July 14 – October 7, 2023)[111]

Online presence

The AGO was the first Canadian museum included in the Google Art Project (later renamed Google Arts & Culture), where 166 pieces from the permanent collection are available for viewing, including works by Paul Gauguin, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Tom Thomson, Emily Carr, Anthony van Dyck, and Gerhard Richter. Currently, there is no "street view" option to tour the museum online.[115][116]

Selected works

Canadian collection

- Tom Thomson, The West Wind, 1917

- Paul Peel, The Young Biologist, 1891

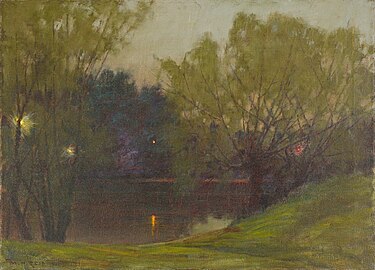

- Mary Hiester Reid, At Twilight, Wychwood Park, 1911

- Tom Thomson, Drowned Land, 1912

- Franklin Carmichael, Autumn Hillside, 1920

- Helen McNicoll, Picking Flowers, c. 1920

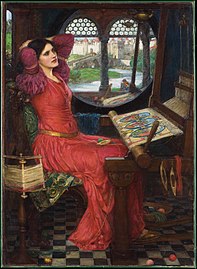

- Emily Carr, The Indian Church, 1929, retitled by the museum as Church at Yuquot Village in 2018.[note 2]

European collection

- Tintoretto – Christ Washing His Disciples' Feet, c. 1545–1555

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Bust of Pope Gregory XV, c. 1621

- Circle of Hans Holbein the Younger – Portrait of King Henry VIII, c. 1560s

- Peter Paul Rubens - Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1611–12

- Peter Paul Rubens – The Raising of the Cross, oil on paper version, c. 1638

- Anthony van Dyck, Daedalus and Icarus, c. 1620

- Frans Hals, Isaak Abrahamsz. Massa, 1626

- Nicolas Poussin, Venus, Mother of Aeneas, presenting him with Arms forged by Vulcan, c. 1636–37

- Claude Lorrain, The Embarkation of Carlo and Ubaldo, 1667

- Jean Siméon Chardin, Jar of Apricots, 1758

- Thomas Gainsborough, The Harvest Wagon, 1784–85

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Seine à Chatou, c. 1871

- Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Antique Pottery Painter: Sculpturæ vitam insufflat pictura, 1893

- Paul Cézanne, Interior of a forest, c. 1885

Modern and contemporary collections

- James Tissot, The Shop Girl, 1883–1885

- Vincent van Gogh, A woman with a spade, seen from behind, c. 1885

- Paul Gauguin, Nave Nave Fenua from the Noa Noa Series, 1893–94

- Pablo Picasso, La soupe, c. 1902

- Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Mrs. Hastings, 1915

- Augustus John, Marchesa Casati, 1919

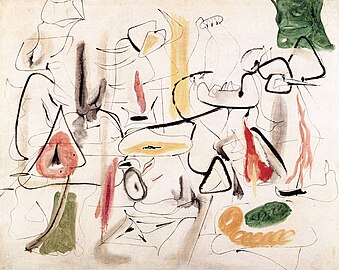

- Arshile Gorky, They Will Take My Island, 1944

- Henry Moore, Two Large Forms, 1969[note 3]

- Evan Penny, Stretch Number 1, 2003

See also

- Culture in Toronto

- List of art museums

- List of museums in Toronto

- List of works by Frank Gehry

- Galeries Ontario / Ontario Galleries

Notes

- ^ In November 2017, a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi sold for US$450.1 million, breaking the previous record set by the sale of Ruben's Massacre of the Innocents in 2002 (US$106 million, adjusted for inflation in 2017).

- ^ The Art Gallery of Ontario renamed the painting to Church at Yuquot Village in 2018. The painting was titled The Indian Church in 1929.

- ^ This photograph was taken when the sculpture was situated at the southwest corner of Dundas Street and McCaul Street. The sculpture was moved to Grange Park in 2017.

References

- ^ "Visitor Figures 2021: the 100 most popular art museums in the world—but is Covid still taking its toll?". The Art Newspaper. March 28, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ AGO Leadership Team

- ^ AGO Board of Trustees

- ^ a b "Art Gallery of Ontario Appoints Xiaoyu Weng as Carol and Morton Rapp, Curator, Modern & Contemporary Art". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. March 11, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ "Ontario Society of Artists". concordia.ca. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ a b O'Rourke, Kate (1997). "Ontario Society of Artists: 125 years". Archivaria. 44: 181–182.

- ^ "AGO Year in Review – List of First Founders" (PDF). AGO. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Osbaldeston 2011, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bradbeer, Janice (January 21, 2016). "Once Upon A City: Art finds a home on The Grange". OurWindsor.ca. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Last Will and Testament of Harriet Goldwin Smith. Archives of Ontario, estate file no. 22382-1909, microfilm MS584, Reel 1822. 1909.

- ^ "The Grange: Overview | AGO Art Gallery of Ontario". www.ago.net. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Heritage Property Research and Evaluation Report: The Grange and Grange Park" (PDF). Heritage Preservation Services. City of Toronto. March 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d McKenzie, Karen; Pfaff, Larry (1980). "The Art Gallery of Ontario Sixty Years of Exhibitions, 1906-1966". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 7 (1–2): 62. doi:10.7202/1076877ar.

- ^ a b c d e f Nakamura 2012, p. 423.

- ^ a b c d Stoffman, Judy (January 28, 2018). "'A man of elegance, grace and good judgment'". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Nakamura 2012, p. 421.

- ^ a b c d e Marshall 2017, p. 83.

- ^ a b "Canadian Architect". Canadian Architect. 38 (9): 24. September 1993.

- ^ a b c Osbaldeston 2011, p. 190.

- ^ DePalma, Anthony (December 8, 1996). "No Stomach for Art". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Kennicott, Philip (November 30, 2008). "A Complex Legacy". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Hume, Christopher (February 22, 2009). "Art in his blood and steel in his bones". Toronto Star. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ "Kenneth Thomson – a "Great Canadian"". Art Matters blog. Art Gallery of Ontario. June 12, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ "Returning Nazi-looted art in Canada". www.lootedart.com. Canadian Jewish News. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

The Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) has 46 paintings and sculptures with what curators call "a gap in provenance," meaning the history of ownership, in this case between 1933 and 1945, has disappeared. Across the country, in public galleries large and small, there are similar mysteries. To date, three Canadian galleries (the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the National Art Gallery in Ottawa and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) have returned looted Holocaust-era paintings to heirs.

- ^ "Spoliation Research". Art Gallery of Ontario. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Renaming of Emily Carr painting spurs debate about reconciliation in art". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. May 23, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "'That Is a Word That Causes Pain': A Toronto Museum Takes 'Indian' Out of the Title of an Emily Carr Painting". Artnet News. Artnet Worldwide Corporation. May 23, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "The kids are alright: Art Gallery of Ontario offers free admission for visitors 25 and under, and reduced yearly passes for all". www.theartnewspaper.com. May 9, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "Looted Art Commission - CLAE News". www.lootedartcommission.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

n 18 November 2020 the Commission jointly with the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada (AGO) announced the restitution of Still Life with Flowers by Jan van Kessel the Elder to the heirs of Dagobert and Martha David. In March 2020, the Commission made the restitution claim on behalf of the family, providing compelling evidence that the painting had formerly belonged to the family who had fled Germany to Belgium in 1939 only to be trapped there, forced to live in hiding under the German occupation and to sell their possessions in order to survive. Following the painting's forced sale in Brussels, it was traded through Amsterdam and Berlin before it was acquired by the dealer Wildenstein & Co. in London, England. A Canadian purchased the painting from Wildenstein in the early 1950s and donated it to the AGO in 1995.

- ^ "AGO returns painting to family following claim by the Commission for Looted Art in Europe" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2020.

- ^ "AGO returns painting to family following claim by the Commission for Looted Art in Europe". Art Gallery of Ontario. November 18, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Transformation AGO: Project Factsheet". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Grange Park". toronto.ca. City of Toronto. March 6, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Heritage Property Research and Evaluation Report: The Grange and Grange Park" (PDF). Heritage Preservation Services. City of Toronto. March 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ "Heritage easement agreement". City of Toronto. 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Osbaldeston 2011, p. 188.

- ^ Carr, Angela (October 23, 2011). "Architecture of Art Galleries in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Osbaldeston 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Marshall 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Frank Gehry (December 7, 2008). "The Art Gallery of Ontario". designboom.com. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c Boake, Terri Meyer (2013). Understanding Steel Design: An Architectural Design Manual. Walter de Greyter. pp. 208–210. ISBN 978-3-0346-1048-3.

- ^ a b c d e Art Gallery of Ontario: Renovation and Addition. Canadian Wood Council. 2009. p. 5.

- ^ a b Art Gallery of Ontario: Renovation and Addition. Canadian Wood Council. 2009. p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Art Gallery of Ontario: Renovation and Addition. Canadian Wood Council. 2009. p. 6.

- ^ a b Art Gallery of Ontario: Renovation and Addition. Canadian Wood Council. 2009. p. 7.

- ^ Bradshaw, James (November 14, 2008). "Finished AGO puts Gehry's fears to rest". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ Hume, Christopher (November 13, 2008). "Revamped AGO a modest masterpiece". Toronto Star. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (November 14, 2008). "Gehry Puts a Very Different Signature on His Old Hometown's Museum". The New York Times. p. C1. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Piacente, Maria; Lord, Barry (2014). Manual of Museum Exhibitions. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7591-2271-0.

- ^ "New David Milne Centre - AGO Press Release". AGO.ca. April 3, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ "General Information Fact Sheet". Art Gallery of Ontario. September 14, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Art, technology and archives unite at the AGO's new David Milne Centre" (Press release). Art Gallery of Ontario. April 13, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Adams, James (April 9, 2012). "AGO study centre to highlight David Milne". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "Come and knock on our (new) door". AGO Art Matters blog. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "The J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous and Canadian Art".

- ^ "AGO selects team to lead the design of its expansion project". Canadian Architect. April 27, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Bozikovic, Alex (April 27, 2022). "The Art Gallery of Ontario launches a major expansion with 'super-subtle' architecture". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ Alberga, Hannah (March 3, 2023). "AGO reveals what its major expansion will look like". toronto.ctvnews.ca. Bell Media. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Nakamura 2012, p. 422.

- ^ a b "The African Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Martin, Sandra (May 28, 2013). "Murray Frum, developer and art collector, dies at 81". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Keene, Bryan C. (2019). Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts. Getty Publications. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-6060-6598-3.

- ^ a b c "The Indigenous Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Thomson Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Canadian Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Nakamura 2012, p. 430.

- ^ a b c d Nakamura 2012, p. 428.

- ^ a b c d Humeniuk, Gregory (2014). "Reframing Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven in the Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario: From Principles to Practice/Recadrage des oeuvres de Tom Thomson et du Groupe des sept figurant dans la collection Thomson du Musée des beaux-arts de l'Ontario: des principes à la pratique". Journal of Canadian Art History. 35 (2): 141142.

- ^ a b c d Bresge, Adina (June 28, 2018). "Toronto gallery to unveil cross-cultural Canadian and Indigenous art centre". The National Post. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Dobrzynski, Judith H. (June 29, 2018). "Indigenous art comes first in Art Gallery of Ontario's new Canadian galleries". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ McMaster 2009, p. 216.

- ^ McMaster 2009, p. 220.

- ^ McMaster 2009, p. 217.

- ^ "AGO to sell up to 20 A.Y. Jackson paintings to make room for underrepresented artists". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. January 14, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ "Please be seated". Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Nakamura 2012, p. 424.

- ^ "The J. S. McLean Centre for Indigenous and Canadian Art". Canadian Art. July 1, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Nakamura 2012, p. 426.

- ^ a b c d "The Contemporary Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Mudhar, Raju (April 4, 2019). "Ready for your selfie? AGO's permanent Kusama Infinity Mirrored Room now open". The Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The European Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Alleyne, Allyssia (December 9, 2016). "500-year-old secrets of boxwood miniatures unlocked". CNN. Turner Broadcasting Systems, Inc. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Ian (November 4, 2016). "AGO exhibit raises profound questions about ancient handmade objects". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "'Too naked, too violent': The Art Gallery of Ontario's troubling $100M masterpiece hits the road". The Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation. August 10, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Kinsella, Eilseen (November 15, 2017). "The Last Known Painting by Leonardo da Vinci Just Sold for $450.3 Million". ARTnews. Art Media Holdings. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Ditmars, Hadani (August 23, 2019). "Art Gallery of Ontario acquires a Caillebotte after long legal struggle". The Art Newspaper. Umberto Allemandi & Co. Publishing Ltd. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Modern Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Canada. Penguin. 2018. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4654-7778-1.

- ^ Marshall 2017, p. 82.

- ^ Marshall 2017, p. 81–82.

- ^ a b c "The Photography Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Dawson, Aimee (December 18, 2017). "The top ten museum acquisitions of 2017". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ a b c Reid, Tashauna (June 6, 2019). "AGO acquires large collection of historical Caribbean photographs". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "The Prints and Drawings Collection". ago.ca. Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Hustak, Brian (December 3, 2008). "Betty Goodwin was a giant in Canadian art". Vancouver Sun. Postmedia Network Inc. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "The bleak but compassionate art of Käthe Kollwitz". TVO Current Affairs. The Ontario Educational Communications Authority. November 1, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "The AGO's Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives". Art Gallery of Ontario.

- ^ a b "Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives". Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ "Other Libraries". ocadu.ca. OCAD University. 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Horizon Information Portal". ago.net.

- ^ "Edward P. Taylor Research Library: Thomson Collection Resource Guide" (PDF). Art Gallery of Ontario. 2011.

- ^ "Library & Archives Collection". Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Margaux Williamson is the Art Gallery of Ontario's current artist-in-residence". Toronto Star. March 22, 2012.

- ^ 25k Mocca Award honours arts patrons partners in art. CBC News.

- ^ a b AGO Launches Artist-in-Residence Program with Winnipeg-born Artist Paul Butler | newz4u.net

- ^ Ontario, Art Gallery of. "Indian artist Gauri Gill wins $50,000 Grange Prize :: AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize". www.ago.net. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Reason to Love Toronto: yoga classes at the Art Gallery of Ontario". Toronto Life. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Sarah Lazarovic (November 12, 2011). "Why the Art Gallery of Ontario wants you to stretch among the sculptures". National Post.

- ^ Art Gallery of Ontario offers yoga Archived March 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sky Goodden, ARTINFO Canada. "AGO Announces New Artist-in-Residence, the Celebrated Hiraki Sawa". Artinfo.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah "Artist-in-Residence | AGO Art Gallery of Ontario". www.ago.net. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Lorinc, John (September 14, 2012). "A graffitist who works on the city's dime". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Qatari Sheikh's Unpaid Auction Tab, Corcoran Seeks 'Visionary Leader', and More". Artinfo.

- ^ "Artist-in-Residence". Art Gallery of Ontario. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ Wright, Matthew. "Art Gallery of Ontario becomes the first Canadian museum to participate in the Google Art Project". National Post. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Art Gallery of Ontario". Retrieved January 30, 2016.

Further reading

- Marshall, Christopher R. (2017). Sculpture and the Museum. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3515-4955-4.

- McMaster, Gerald (2009). "Art History Through the Lens of the Present?". Journal of Museum Education. 34 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1080/10598650.2009.11510638. S2CID 194089306.

- Nakamura, Naohiro (2012). "The representation of First Nations art at the Art Gallery of Ontario". International Journal of Canadian Studies. 45–46 (45–46): 417–440. doi:10.7202/1009913ar.

- Osbaldeston, Mark (2011). Unbuilt Toronto 2: More of the City That Might Have Been. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-0093-2.

External links

- Official website

- Art Gallery of Ontario within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Art Gallery of Ontario at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art Gallery of Ontario at Wikimedia Commons

![Emily Carr, The Indian Church, 1929, retitled by the museum as Church at Yuquot Village in 2018.[note 2]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Emily_Carr_Indian_Church.jpg/169px-Emily_Carr_Indian_Church.jpg)

![Henry Moore, Two Large Forms, 1969[note 3]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ea/Two_Forms_by_Henry_Moore.jpg/360px-Two_Forms_by_Henry_Moore.jpg)