Armenian genocide denial

Armenian genocide denial is the negationist claim that the Ottoman Empire and its ruling party, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), did not commit genocide against its Armenian citizens during World War I—a crime documented in a large body of evidence and affirmed by the vast majority of scholars.[2][3] The perpetrators denied the genocide as they carried it out, claiming that Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were resettled for military reasons, not exterminated. In its aftermath, incriminating documents were systematically destroyed. Denial has been the policy of every government of the Ottoman Empire's successor state, the Republic of Turkey, as of 2024.

Borrowing arguments used by the CUP to justify its actions, Armenian genocide denial rests on the assumption that the deportation of Armenians was a legitimate state action in response to a real or perceived Armenian uprising that threatened the empire's existence during wartime. Deniers assert the CUP intended to resettle Armenians, not kill them. They claim the death toll is exaggerated or attribute the deaths to other factors, such as a purported civil war, disease, bad weather, rogue local officials, or bands of Kurds and outlaws. The historian Ronald Grigor Suny summarizes the main argument as "there was no genocide, and the Armenians were to blame for it".[4]

A critical reason for denial is that the genocide enabled the establishment of a Turkish nation-state; recognizing it would contradict Turkey's founding myths.[5] Since the 1920s, Turkey has worked to prevent recognition or even mention of the genocide in other countries. It has spent millions of dollars on lobbying, created research institutes, and used intimidation and threats. Denial affects Turkey's domestic policies and is taught in Turkish schools; some Turkish citizens who acknowledge the genocide have faced prosecution for "insulting Turkishness". Turkey's century-long effort to deny the genocide sets it apart from other historical cases of genocide.[6]

Azerbaijan, a close ally of Turkey, also denies the genocide and campaigns against its recognition internationally. Most Turkish citizens and political parties support Turkey's denial policy. Scholars argue that Armenian genocide denial has set the tone for the government's attitude towards minorities, and has contributed to the ongoing violence against Kurds in Turkey. A 2014 poll of 1,500 people conducted by EDAM, a Turkish think tank, found that nine percent of Turkish citizens recognize the genocide.[7][8]

Background

The presence of Armenians in Anatolia is documented since the sixth century BC, almost two millennia before Turkish presence in the area.[10][11] The Ottoman Empire effectively treated Armenians and other non-Muslims as second-class citizens under Islamic rule, even after the nineteenth-century Tanzimat reforms intended to equalize their status.[12] By the 1890s, Armenians faced forced conversions to Islam and increasing land seizures, which led a handful to join revolutionary parties such as the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, also known as Dashnaktsutyun).[13] In the mid-1890s, state-sponsored Hamidian massacres killed at least 100,000 Armenians, and in 1909, the authorities failed to prevent the Adana massacre, which resulted in the death of some 17,000 Armenians.[14][15][16] The Ottoman authorities denied any responsibility for these massacres, accusing Western powers of meddling and Armenians of provocation, while presenting Muslims as the main victims and failing to punish the perpetrators.[17][18][19] These same tropes of denial would be employed later to deny the Armenian genocide.[19][20]

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) came to power in two coups in 1908 and in 1913.[21] In the meantime, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its European territory in the Balkan Wars; the CUP blamed Christian treachery for this defeat.[22] Hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees fled to Anatolia as a result of the wars; many were resettled in the Armenian-populated eastern provinces and harbored resentment against Christians.[23][24] In August 1914, CUP representatives appeared at an ARF conference demanding that in the event of war with the Russian Empire, the ARF incite Russian Armenians to intervene on the Ottoman side. The ARF declined, instead declaring that Armenians should fight for the countries in which they were citizens.[25] In October 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers.[26]

Armenian genocide

During the Ottoman invasion of Russian and Persian territory in late 1914, Ottoman paramilitaries massacred local Armenians.[27] A few Ottoman Armenian soldiers defected to Russia—seized upon by both the CUP and later deniers as evidence of Armenian treachery—but the Armenian volunteers in the Russian army were mostly Russian Armenians.[28][29][30] Massacres turned into genocide following the catastrophic Ottoman defeat by Russia in the Battle of Sarikamish (January 1915), which was blamed on Armenian treachery. Armenian soldiers and officers were removed from their posts pursuant to a 25 February order issued by Minister of War Enver Pasha.[27][31] In the minds of the Ottoman leaders, isolated incidents of Armenian resistance were taken as evidence of a general insurrection.[32]

In mid-April, after Ottoman leaders had decided to commit genocide,[34] Armenians barricaded themselves in the eastern city of Van.[35] The defense of Van served as a pretext for anti-Armenian actions at the time and remains a crucial element in works that seek to deny or justify the genocide.[36] On 24 April, hundreds of Armenian intellectuals were arrested in Constantinople. Systematic deportation of Armenians began, given a cover of legitimacy by the 27 May deportation law. The Special Organization guarded the deportation convoys consisting mostly of women, children, and the elderly who were subject to systematic rape and massacres. Their destination was the Syrian Desert, where those who survived the death marches were left to die of starvation or disease in makeshift camps.[37] Deportation was only carried out in the areas away from active fighting; near the front lines, Armenians were massacred outright.[38] The leaders of the CUP ordered the deportations, with interior minister Talat Pasha, aware that he was sending the Armenians to their deaths, taking a leading role.[39] In a cable dated 13 July 1915, Talat stated that "the aim of the Armenian deportations is the final solution of the Armenian Question."[40]

Historians estimate that 1.5 to 2 million Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire in 1915, of whom 800,000 to 1.2 million were deported during the genocide. In 1916, a wave of massacres targeted the surviving Armenians in Syria; by the end of the year, only 200,000 were still alive.[41] An estimated 100,000 to 200,000 women and children were integrated into Muslim families through such methods as forced marriage, adoption and conversion.[42][43] The state confiscated and redistributed property belonging to murdered or deported Armenians.[44][45] During the Russian occupation of eastern Anatolia, Russian and Armenian forces massacred as many as 60,000 Muslims. Making a false equivalence between these killings and the genocide is a central argument of denial.[46][47]

The genocide is documented extensively in Ottoman archives, documents collected by foreign diplomats (including those from neutral countries and Ottoman allies), eyewitness reports by Armenian survivors and Western missionaries, and the proceedings of the Ottoman Special Military Tribunals.[2] Talat Pasha kept his own statistical record, which revealed a massive discrepancy between the number of Armenians deported in 1915 and those surviving in 1917.[48][49] The vast majority of non-Turkish scholars accept the genocide as a historical fact, and an increasing number of Turkish historians are also acknowledging and studying the genocide.[3]

Origins

Ottoman Empire

Genocide denial is the minimization of an event established as genocide, either by denying the facts or by denying the intent of the perpetrators.[50] Denial was present from the outset as an integral part of the Armenian genocide, which was perpetrated under the guise of resettlement.[51][52] Denial emerged because of the Ottoman desire to maintain American neutrality in the war and German financial and military support.[53]

In May 1915, Russia, Britain, and France sent a diplomatic communiqué to the Ottoman government condemning the Ottoman "crimes against humanity" and threatening to hold accountable any Ottoman officials who were responsible.[55] The Ottoman government denied that massacres of Armenians had occurred, and said that Armenians colluded with the enemy, while asserting that national sovereignty allowed them to take measures against the Armenians. It also alleged that Armenians had massacred Muslims and accused the Allies of committing war crimes.[56]

In early 1916, the Ottoman government published a two-volume work titled The Armenian Aspirations and Revolutionary Movements, denying it had tried to exterminate the Armenian people.[57] At the time, little credence was given to such statements internationally,[58] but some Muslims, previously ashamed by crimes against Armenians, changed their mind in response to propaganda about atrocities allegedly committed by Armenians.[59] The themes of genocide denial that originated during the war were later recycled in Turkey's denial of the genocide.[52][58]

Turkish nationalist movement

The Armenian genocide itself played a key role in the destruction of the Ottoman Empire and the foundation of the Turkish republic.[5] The destruction of the Christian middle class, and redistribution of their properties, enabled the creation of a new Muslim/Turkish bourgeoisie.[60][61][62] There was significant continuity between the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, and the Republican People's Party was the successor of the Committee of Union and Progress that carried out the genocide.[63][64] The Turkish nationalist movement depended on support from those who had perpetrated the genocide or enriched themselves from it, creating an incentive for silence.[65][66] Denial and minimization of wartime atrocities was crucial to the formation of a Turkish nationalist consensus.[67]

Following the genocide, many survivors sought an Armenian state in eastern Anatolia; warfare between Turkish nationalists and Armenians was fierce, atrocities being committed on both sides. Later political demands and Armenian killings of Muslims have often been used to retroactively justify the 1915 genocide.[68][69] The Treaty of Sèvres granted Armenians a large territory in eastern Anatolia, but this provision was never implemented because of the Turkish invasion of Armenia in 1920.[70][71] Turkish troops conducted massacres of Armenian survivors in Cilicia and killed around 200,000 Armenians following the invasion of the Caucasus and the First Republic of Armenia; thus, historian Rouben Paul Adalian has argued that "Mustafa Kemal [the leader of the Turkish nationalist movement] completed what Talaat and Enver had started in 1915."[72][73][74]

The Ottoman government in Constantinople held courts-martial of a handful of perpetrators in 1919 to appease Western powers. Even so, the evidence was sabotaged, and many perpetrators were encouraged to escape to the interior. The reality of state-sponsored mass killing was not denied, but many circles of society considered it necessary and justified.[75][76] As a British Foreign Office report stated, "not one Turk in a thousand can conceive that there might be a Turk who deserves to be hanged for the killing of Christians."[77] Kemal repeatedly accused Armenians of plotting the extermination of Muslims in Anatolia.[78] He contrasted the "murderous Armenians" to Turks, portrayed as a completely innocent and oppressed nation.[79] In 1919, Kemal defended the Ottoman government's policies towards Christians, saying "Whatever has befallen the non-Muslim elements living in our country, is the result of the policies of separatism they pursued in a savage manner, when they allowed themselves to be made tools of foreign intrigues and abused their privileges."[80][81]

In Turkey

Causes

Historian Erik-Jan Zürcher argues that, since the Turkish nationalist movement depended on the support of a broad coalition of actors that benefitted from the genocide, it was impossible to break with the past.[65] From the founding of the republic, the genocide has been viewed as a necessity and raison d'état.[84][85] Many of the main perpetrators, including Talat Pasha, were hailed as national heroes of Turkey; many schools, streets, and mosques are still named after them.[86] Those convicted and sentenced to death by the postwar tribunal for crimes against Armenians, such as Mehmet Kemal and Behramzade Nusret, were proclaimed national and glorious martyrs and their families were rewarded by the state with confiscated Armenian properties.[77][87] Turkish historian Taner Akçam states that, "It's not easy for a nation to call its founding fathers murderers and thieves."[88] Kieser and other historians argue that "the single most important reason for this inability to accept culpability is the centrality of the Armenian massacres for the formation of the Turkish nation-state."[5] Turkish historian Doğan Gürpınar says that acknowledging the genocide would bring into question the foundational assumptions of the Turkish nation-state.[89]

One factor in explaining denial is Sèvres syndrome, a popular belief that Turkey is besieged by implacable enemies.[90][91] Despite the unlikelihood that recognition would lead to any territorial changes, many Turkish officials believe that genocide recognition is part of a plot to partition Turkey or extract other reparations.[92][93][94] Acknowledgement of the genocide is perceived by the state as a threat to Turkey's national security, and Turks who do so are seen as traitors.[95][96] During his fieldwork in an Anatolian village in the 1980s, anthropologist Sam Kaplan found that "a visceral fear of Armenians returning ... and reclaiming their lands still gripped local imagination".[97]

Destruction and concealment of evidence

An edict of the Ottoman government banned foreigners from taking photographs of Armenian refugees or the corpses that accumulated on the sides of the roads on which death marches were carried out. Violators were threatened with arrest.[98] Strictly enforced censorship laws prevented Armenian survivors from publishing memoirs, prohibiting "any publication at odds with the general policies of the state".[99][100] Those who acknowledge the genocide have been prosecuted under laws against "insulting Turkishness".[93] Talat Pasha had decreed that "everything must be done to abolish even the word 'Armenia' in Turkey".[101] In the postwar Turkish republic, Armenian cultural heritage has been subject to systematic destruction in an attempt to eradicate the Armenian presence.[102][101] On 5 January 1916, Enver Pasha ordered all place names of Greek, Armenian, or Bulgarian origin to be changed, a policy fully implemented in the later republic, continuing into the 1980s.[103] Mass graves of genocide victims have also been destroyed, although many still exist.[104] After the 1918 armistice, incriminating documents in the Ottoman archives were systematically destroyed.[105] The records of the postwar courts-martial in Constantinople have also disappeared.[106][107] Recognizing that some archival documents supported its position, the Turkish government announced that the archives relevant to the "Armenian question" would be opened in 1985.[108] According to Turkish historian Halil Berktay, diplomat Nuri Birgi conducted a second purge of the archives at this time.[109] The archives were officially opened in 1989,[108] but in practice, some archives remained sealed, and access to other archives was restricted to scholars sympathetic to the official Turkish narrative.[110][111]

Turkish historiography

In Mustafa Kemal's 1927 Nutuk speech, which was the foundation of Kemalist historiography, the tactics of silence and denial are employed to deal with violence against Armenians. As in his other speeches, he presents Turks as innocent of any wrongdoing and as victims of horrific Armenian atrocities.[112][113][114] For decades, Turkish historiography ignored the Armenian genocide. One of the early exceptions was the genocide perpetrator Esat Uras, who published The Armenians in History and the Armenian Question in 1950. Uras's book, probably written in response to post–World War II Soviet territorial claims, was a novel synthesis of earlier arguments deployed by the CUP during the war, and linked wartime denial with the "official narrative" on the genocide developed in the 1980s.[115][116]

In the 1980s, following Armenian efforts for recognition of the genocide and a wave of assassinations by Armenian militants, Turkey began to present an official narrative of the "Armenian question", which it framed as an issue of contemporary terrorism rather than historical genocide. Retired diplomats were recruited to write denialist works, completed without professional methodology or ethical standards and based on cherry-picking archival information favorable to Turks and unfavorable to Armenians.[117][118][119] The Council of Higher Education was set up in 1981 by the Turkish military junta, and has been instrumental in cementing "an alternative, 'national' scholarship with its own reference system", according to Gürpınar.[120][108] Besides academic research, Türkkaya Ataöv taught the first university course on the "Armenian question" in 1983.[108] By the twenty-first century, the Turkish Historical Society, known for publications upholding the official position of the Turkish government, had as one of its main functions the countering of genocide claims.[121][122][123]

Around 1990, Taner Akçam, working in Germany, was the first Turkish historian to acknowledge and study the genocide.[124] During the 1990s, private universities began to be established in Turkey, enabling challenges to state-sponsored views.[125] In 2005, academics at three Turkish universities organized an academic conference dealing with the genocide. Scheduled to be held in May 2005, the conference was suspended following a campaign of intimidation, but eventually held in September.[126][127][128] The conference represented the first major challenge to Turkey's founding myths in the public discourse of the country[128] and resulted in the creation of an alternative, non-denialist historiography by elite academics in Istanbul and Ankara, in parallel to an ongoing denialist historiography.[129][130] Turkish academics who accept and study the genocide as fact have been subjected to death threats and prosecution for insulting Turkishness.[131][132] Western scholars generally ignore the Turkish denialist historiography because they consider its methods unscholarly—especially the selective use of sources.[133][134]

Education

Turkish schools, public or private, are required to use history textbooks approved by the Ministry of Education.[135][136][138] The state uses this monopoly to increase support for the official denialist position,[136][139] vilifying Armenians and presenting them as enemies.[140][141] For decades, these textbooks did not mention Armenians as part of Ottoman history.[142][143][144] Since the 1980s, textbooks discuss the "events of 1915", but deflect the blame from the Ottoman government to other actors. They accuse imperialist powers of manipulating the Armenians to undermine the empire, and allege that the Armenians committed treason or presented a threat. Some textbooks admit that deportations occurred and Armenians died, but present this action as necessary and justified. Since 2005, textbooks have accused Armenians of perpetrating genocide against Turkish Muslims.[143][145][146] In 2003, students in each grade level were instructed to write essays refuting the genocide.[147]

Society

For decades, the genocide was a taboo subject in Turkish society.[148] Göçek states that it is the interaction between state and society that makes denial so persistent.[149] Besides the Turkish state, Turkish intellectuals and civil society have also denied the genocide.[150] Turkish fiction dealing with the genocide typically denies it, while claiming the fictional narrative is based on true events.[151] Noting many people in eastern Turkey have passed down memories of the event, genocide scholar Uğur Ümit Üngör says that "the Turkish government is denying a genocide that its own population remembers."[152] The Turkish state and most of society have engaged in similar silencing regarding other ethnic persecutions and human rights violations in the Ottoman Empire and Republican Turkey against Greeks, Assyrians, Kurds, Jews and Alevis.[55][153][154]

Most Turks support the state's policies with regard to genocide denial. Some admit that massacres occurred but regard them as justified responses to Armenian treachery.[155][156] Many still consider Armenians to be a fifth column.[68] According to Halil Karaveli, "the word [genocide] incites strong, emotional reactions among Turks from all walks of society and of every ideological inclination".[157] Turkish–Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was outspoken in his advocacy for facing historical truths to achieve a better society and reconciliation between ethnic groups. He was prosecuted for insulting Turkishness and was assassinated in 2007 by a Turkish ultranationalist.[158][159] In 2013, a study sampling Turkish university students in the United States found that 65% agreed with the official view that Armenian deaths occurred as a result of "inter-communal warfare" and that another 10% blamed Armenians for causing the violence.[160] A 2014 survey found that only 9% of Turkish citizens thought their government should recognize the genocide.[7][8] Many believe that such an acknowledgement is imposed by Armenians and foreign powers with no benefit to Turkey.[161] Many Kurds, who themselves have suffered political repression in Turkey, have recognized and condemned the genocide.[162][163]

Politics

The Islamic conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002[164][165] and took an approach to history that was critical of both the CUP and the early Republican era. This position initially led to some liberalization and a wider range of views that could be expressed in the public sphere. The AKP presented its approach to the "events of 1915" as an alternative to genocide denial and genocide recognition, by emphasizing shared suffering.[166][167] Over time, and especially since the 2016 failed coup, the AKP government became increasingly authoritarian; political repression and censorship has made it more difficult to discuss controversial topics such as the Armenian genocide.[168] As of 2020, all major political parties in Turkey, except the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), as well as many pro- and anti-government media and civil society organizations, support denial. Both government and opposition parties have strongly opposed genocide recognition in other countries.[169] No Turkish government has admitted what happened to the Armenians was a crime, let alone a genocide.[170][171][172] On 24 April 2019, president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan tweeted, "The relocation of the Armenian gangs and their supporters ... was the most reasonable action that could be taken in such a period".[173]

Foreign relations of Turkey

Turkish efforts to project its genocide denial overseas date to the 1920s,[174][175] or, alternately, to the genocide itself.[176][177] Turkey's century-long effort to deny the Armenian genocide sets this genocide apart from others in history. According to genocide scholar Roger W. Smith, "In no other instance has a government gone to such extreme lengths to deny that a massive genocide took place."[6] Central to Turkey's ability to deny the genocide and counter its recognition is the country's strategic position in the Middle East, Cold War alliance with the West, and membership of NATO.[178][179] Historians have described the role of other countries in enabling Turkey's genocide denial as a form of collusion.[180][181][182]

At the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923, Turkish representatives repeated the version of Armenian history that had been developed during the war.[183] The resulting Treaty of Lausanne annulled the previous Treaty of Sèvres which had mandated the prosecution of Ottoman war criminals and the restoration of property to Christian survivors. Instead, Lausanne granted impunity to all perpetrators.[184][185] After the 1980 Turkish military coup, Turkey developed more institutionalized ways of countering genocide claims. In 1981, the foreign ministry established a dedicated office (İAGM) specifically to promote Turkey's view of the Armenian genocide.[186] In 2001, a further centralization created the Committee to Coordinate the Struggle with the Baseless Genocide Claims (ASİMKK). The Institute for Armenian Research, a think tank which focuses exclusively on the Armenian issue, was created in 2001 following the French Parliament's recognition of the genocide.[187] ASİMKK disbanded after the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum.[188]

According to sociologist Levon Chorbajian, Turkey's "modus operandi remains consistent throughout and seeks maximalist positions, offers no compromise though sometimes hints at it, and employs intimidation and threats."[189][178] Motivated by belief in a global Jewish conspiracy, the Turkish foreign ministry has recruited Turkish Jews to participate in denialist efforts. Turkish Jewish leaders helped defeat resolutions recognizing the genocide, and avoid mentioning it at academic conferences and in Holocaust museums.[190] As of 2015, Turkey spends millions of dollars each year lobbying against the genocide's recognition.[191] Akçam stated in 2020 that Turkey has definitively lost the information war over the Armenian genocide on both the academic and diplomatic fronts, its official narrative being treated like ordinary denialism.[188]

Germany

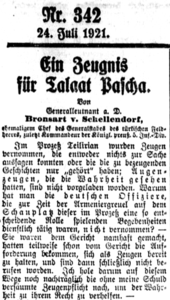

From 1915 to 1918, Germany and the Ottoman Empire undertook "joint propaganda efforts of denial."[193] German newspapers repeated the Ottoman government's denial of committing atrocities and stories of alleged Armenian treachery.[194][195] The government censorship handbook mandated strict limits on speech about Armenians, although penalties for violations were light.[196] On 11 January 1916, socialist deputy Karl Liebknecht raised the issue of the Armenian genocide in the Reichstag, receiving the reply that the Ottoman government "has been forced, due to the seditious machinations of our enemies, to transfer the Armenian population of certain areas, and to assign them new places of residence." Laughter interrupted Liebknecht's follow-up questions.[197][198] During the 1921 trial of Soghomon Tehlirian for the assassination of Talat Pasha, so much evidence was revealed that denial became untenable. German nationalists instead portrayed what they acknowledged as the intentional extermination of the Armenian people as justified.[199]

In March 2006, Turkish nationalist groups organized two rallies in Berlin intended to commemorate "the murder of Talat Pasha" and protest "the lie of genocide." German politicians criticized the march, and turnout was low.[200] When the Bundestag voted to recognize the Armenian genocide in 2016, Turkish media harshly criticized the resolution and eleven deputies of Turkish origin received police protection because of death threats.[201] Germany's large Turkish community has been cited as a reason why the government hesitated,[202] and Turkish organizations lobbied against the resolution and organized demonstrations.[203]

United States

Historian Donald Bloxham states that, "In a very real sense, 'genocide denial' was accepted and furthered by the United States government before the term genocide had even been coined."[204][205] In interwar Turkey, prominent American diplomats like Mark L. Bristol and Joseph Grew endorsed the Turkish nationalist view that the Armenian genocide was a war against the forces of imperialism.[205][206] In 1922, before receiving the Chester concession, Colby Chester argued that Christians of Anatolia were not massacred; his writing exhibited many of the themes of later genocide denial.[207][208] In the 1930s, the Turkish embassy scuttled a planned film adaptation of Franz Werfel's popular novel The Forty Days of Musa Dagh by the American company MGM, threatening a boycott of American films. Turkish embassies, with the support of the US State Department, shot down attempts to revive the film in the 1950s and 1960s.[204][209]

Turkey began political lobbying around 1975.[210] Şükrü Elekdağ, Turkish ambassador to the United States from 1979 to 1989, worked aggressively to counter the trend of Armenian genocide recognition by courting academics, business interests, and Jewish groups.[211] Committee members of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum reported Elekdağ told them that the safety of Jews in Turkey was not guaranteed if the museum covered the Armenian genocide.[212] Under his tenure, the Institute of Turkish Studies (ITS) was set up, funded by $3 million from Turkey, and the country spent $1 million annually on public relations.[211] In 2000, Elekdağ complained ITS had "lost its function and its effectiveness."[210] Turkey threatened to cut off the United States' access to key air bases in Turkey, were it to recognize the genocide.[178] In 2007, a Congressional resolution for genocide recognition failed because of Turkish pressure. Opponents of the bill said a genocide had taken place, but argued against formal recognition to preserve good relations with Turkey.[213] Each year since 1994, the United States president has issued a commemorative message on 24 April. Turkey has sometimes made concessions to keep the president from using the word "genocide".[191][214] In 2019, both houses of Congress passed resolutions formally recognizing the genocide.[179][215] On 24 April 2021, the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, President Joe Biden referred to the events as "genocide" in a statement released by the White House.[216]

United Kingdom

Human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson charged that around 2000, "genocide denial had entrenched itself in the Eastern Department [of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)] ... to such an extent that it was briefing ministers with a bare-faced disregard for readily ascertainable facts", such as its own records from the time.[217] In 2006, in response to a debate initiated by MP Steven Pound, a representative of the FCO said the United Kingdom did not recognize the genocide because "the evidence is not sufficiently unequivocal".[218]

Israel

According to historians Rıfat Bali and Marc David Baer, Armenian genocide denial was the most important factor in the normalization of Israel–Turkey relations.[219] The 1982 International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide, which took place in Tel Aviv, included six presentations on the Armenian genocide. Turkey threatened that if the conference was held, it would close its borders to Jewish refugees from Iran and Syria, putting their lives in danger. As a result, the Israeli Foreign Ministry joined the ultimately unsuccessful effort to cancel the conference.[220]

In April 2001, a Turkish newspaper quoted foreign minister Shimon Peres as saying, "We reject attempts to create a similarity between the Holocaust and the Armenian allegations. Nothing similar to the Holocaust occurred. It is a tragedy what the Armenians went through, but not a genocide."[221][222] According to Charny and Auron, this statement crossed the line into active denial of the Armenian genocide.[223] Scholar Eldad Ben Aharon considers that Peres simply made explicit what had been Israel's policy since 1948.[222] Israel–Turkey relations deteriorated in the late 2010s, but Israel's relations with Azerbaijan are close and the Azerbaijan–Israel International Association has lobbied against recognition of the genocide.[224]

Denialism in academia

Until the twenty-first century, Ottoman and Turkish studies marginalized the killings of Armenians, which many academics portrayed as a wartime measure justified by emergency and avoided discussing in depth. These fields have long enjoyed close institutional links with the Turkish state. Statements by these academics were cited to further the Turkish denial agenda.[225] Historians who recognized the genocide feared professional retaliation for expressing their views.[226][227] The methodology of denial has been compared to the tactics of the tobacco industry or global warming denial: funding of biased research, creating a smokescreen of doubt, and thereby manufacturing a controversy[228][229][230] where there is no genuine academic dispute.[231]

Beginning in the 1980s, the Turkish government has funded research institutes to prevent recognition of the genocide.[232][233][210] On 19 May 1985, The New York Times and The Washington Post ran an advertisement from the Assembly of Turkish American Associations[234] in which 69 academics—most of the professors of Ottoman history working in the United States at the time—called on Congress not to adopt the resolution on the Armenian genocide.[235][236][237] Many of the signatories received research grants funded by the Turkish government, and a majority were not specialists on the late Ottoman Empire.[238][239] Heath Lowry, director of the Institute of Turkish Studies, helped secure the signatures; for his efforts, Lowry received the Foundation for the Promotion and Recognition of Turkey Prize.[240][237] Over the next decade, Turkey funded six chairs of Ottoman and Turkish studies to counter recognition of the genocide; Lowry was appointed to one of the chairs.[240] According to historian Keith David Watenpaugh, the resolution had "a terrible and lasting influence on the rising generation of scholars."[226] In 2000, Elekdağ admitted the statement had become useless because none of the original signatories besides Justin McCarthy would agree to sign another, similar declaration.[234]

More recent academic denialism in the United States has focused on an alleged Armenian uprising, said to justify the persecution of Armenians as a legitimate counterinsurgency.[241] In 2009, the University of Utah opened its "Turkish Studies Project", funded by the Turkish Coalition of America (TCA) and led by M. Hakan Yavuz, with Elekdağ on the advisory board.[242][234] The University of Utah Press has published several books denying the genocide,[241][242] beginning with Guenter Lewy's The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey (2006). Lewy's book had been rejected by eleven publishers and, according to Marc Mamigonian, became "one of the key texts of modern denial".[243][244] TCA has also provided financial support to several authors including McCarthy, Michael Gunter, Yücel Güçlü, and Edward J. Erickson for writing books that deny the Armenian genocide.[242] According to Richard G. Hovannisian, of recent deniers in academia, almost all have connections to Turkey and those with Turkish citizenship have all worked for the Turkish foreign ministry.[245]

Academic integrity controversies

Many scholars consider it unethical for academics to deny the Armenian genocide.[227][246] Beyond that, there have been several controversies about academic integrity relating to denial of the genocide. In 1990, psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton received a letter from Nüzhet Kandemir, Turkish ambassador to the United States, questioning references to the Armenian genocide in one of Lifton's books. The ambassador inadvertently included a draft of a letter from Lowry advising the ambassador on how to prevent mention of the Armenian genocide in scholarly works. Lowry was later named Atatürk Professor of Ottoman Studies at Princeton University, which the Turkish government had endowed with a $750,000 grant. His actions were described as "subversion of scholarship";[247] he later said it was a mistake to have written the letter.[248]

In 2006, Ottomanist historian Donald Quataert—one of the 69 signatories of the 1985 statement to the United States Congress[249]—reviewed The Great Game of Genocide, a book about the Armenian genocide, agreeing that "genocide" was the right word to use;[250] the article challenged what Quataert termed "the Ottomanist wall of silence"[251] on the issue.[249][252][253] Weeks later, he resigned as chairman of the board of directors of the Institute of Turkish Studies after Turkish officials threatened that if he did not retract his statements, the institute's funding would be withdrawn. Several members of the board resigned and both the Middle East Studies Association and Turkish Studies Association criticized the violation of Quataert's academic freedom.[249][252][254]

In a lecture he delivered in June 2011, Akçam stated that a Turkish foreign ministry official told him that the Turkish government was offering money to academics in the United States for denial of the genocide, noting the coincidence between what his source said and Gunter's book Armenian History and the Question of Genocide.[255] Hovannisian believes that books denying the genocide are published because of flaws in peer review leading to "a strong linkage among several mutually sympathetic reviewers" without submitting the books to academics who would point out errors.[256]

Examination of claims

The official Turkish view is based on the belief that the Armenian genocide was a legitimate state action and therefore cannot be challenged on legal or moral grounds.[257] Publications from this point of view share many of the basic facts with non-denialist histories, but differ in their interpretation and emphases.[258] In line with the CUP's justification of its actions, denialist works portray Armenians as an existential threat to the empire in a time of war, while rejecting the CUP's intent to exterminate the Armenian people. Historian Ronald Grigor Suny summarizes the main denialist argument as, "There was no genocide, and the Armenians were to blame for it."[4][259]

Denialist works portray Armenians as terrorists and secessionists,[260] shifting the blame from the CUP to the Armenians.[261][262] According to this logic, the deportations of Armenian civilians was a justified and proportionate response to Armenian treachery, either real or as perceived by the Ottoman authorities.[263][264][265] Proponents cite the doctrine of military necessity and attribute collective guilt to all Armenians for the military resistance of some, despite the fact that the law of war criminalizes the deliberate killing of civilians.[266][267] Deaths are blamed on factors beyond the control of the Ottoman authorities, such as weather, disease, or rogue local officials.[268][269] The role of the Special Organization is denied[270][271] and massacres are instead blamed on Kurds,[60] "brigands", and "armed gangs" that supposedly operated outside the control of the central government.[272]

Other arguments include:

- That there was a "civil war" or generalized Armenian uprising planned by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) in collusion with Russia.[273][274] Neither Ottoman archives nor other sources support this hypothesis, as admitted by one proponent of this theory, Edward Erickson.[263][275][276]

- That the number of Armenians who died was 300,000 or fewer, perhaps no more than 100,000.[277] Bloxham sees this as part of a more general theme of deliberately understating the Armenian presence in the Ottoman Empire to undermine any demands for autonomy or independence.[278]

- That certain groups of Armenians were spared, which proponents argue proves there was no systematic effort to exterminate the Armenian people.[279] Some have falsely claimed that Catholic and Protestant Armenians and the families of Armenian soldiers serving in the Ottoman Army were not deported.[280] The survival of the Armenians of Smyrna and Constantinople—planned by the CUP but only partially carried out because of German pressure—is also cited to deny that the CUP leadership had genocidal intent.[281][282]

- False assertions that the Ottoman rulers took actions to safeguard Armenian lives and property during their deportation, and prosecuted 1,397 people for harming Armenians during the genocide.[283][284]

- That many of the sources cited by historians of the genocide are unreliable or forged, including the accounts of Armenian survivors and Western diplomats[2][285] and the records of the Ottoman Special Military Tribunal,[286][287][288] to the point that the Prime Ministerial Ottoman Archive is considered the only reliable source.[289]

- The assertion that Turks are incapable of committing genocide, an argument often supported by exaggerated claims of Ottoman and Turkish benevolence towards Jews.[290] At an official ceremony to commemorate the Holocaust in 2014, Turkish foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu claimed that, in contrast to Christian Europe, "There is no trace of genocide in our history."[291] During a visit to Sudan in 2006, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan denied there had been a Darfur genocide because "a Muslim cannot commit genocide".[292][293]

- That claims of genocide stem from a prejudiced, anti-Turkish or Orientalist worldview.[242]

- At the extreme end of denialist claims is that it is not Turks who committed genocide against Armenians but vice versa, as articulated by the Iğdır Genocide Memorial and Museum.[1]

Denial of the Armenian genocide is compared frequently to Holocaust denial because of similar tactics of misrepresenting evidence, false equivalence, claiming that atrocities were invented by war propaganda and that powerful lobbies manufacture genocide allegations for their own profit, subsuming one-sided systematic extermination into war deaths, and shifting blame from the perpetrators to the victims of genocide. Both forms of negationism share the goal of rehabilitating the ideologies which brought genocide about.[176][294]

Legality

According to former International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judge Flavia Lattanzi, the present Turkish government's "denial of past Ottoman and Turkish authorities' wrongdoings is a new violation of international law".[295]

Some European countries have adopted laws to criminalize denial of the genocide;[296] such laws are controversial, opponents arguing that they erode freedom of speech.[297] In 1993, French newspapers printed several interviews with British-American historian Bernard Lewis in which he argued there was no Armenian genocide because the Armenians brought their fate upon themselves.[298][299] A French state prosecutor brought criminal proceedings against him for these statements under the Gayssot Law. The prosecution failed, as the court determined that the law did not apply to events before World War II.[300] In a 1995 civil proceeding brought by three Armenian genocide survivors, a French court censured Lewis' remarks under Article 1382 of the Civil Code and fined him one franc, and ordering the publication of the judgment at Lewis' cost in Le Monde. The court ruled that while Lewis has the right to his views, their expression harmed a third party and that "it is only by hiding elements which go against his thesis that the defendant was able to state there was no 'serious proof' of the Armenian Genocide".[301][302][303]

In March 2007, a Swiss court found Doğu Perinçek, a member of the Talat Pasha Committee (named after the main perpetrator of the genocide),[304][305][306] guilty under the Swiss law that outlawed genocide denial. Perinçek appealed; in December,[307] the Swiss Supreme Court confirmed his sentence.[308][307] The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) overturned the verdict in Perinçek v. Switzerland on freedom of speech grounds.[309] Since the ECtHR has ruled that member states may criminalize Holocaust denial, the verdict has been criticized for creating a double standard between the Holocaust and other genocides, along with failure to acknowledge anti-Armenianism as a motivation for genocide denial.[305][310][311] Although the court did not rule on whether the events of 1915 constituted genocide, several separate opinions recognized the genocide as a historical fact.[309] Perinçek misrepresented the verdict by saying, "We put an end to the genocide lie."[312]

Consequences

Kieser, Göçek, and Cheterian state that ongoing denial prevents Turkey from achieving a full democracy including pluralism and human rights, and that this denial fosters state repression of minority groups in Turkey, especially Kurds.[313] Akçam says that genocide denial "rationaliz[es] the violent persecution of religious and ethnic minorities" and desensitizes the population to future episodes of mass violence.[314] Until the Turkish state acknowledges genocide, he argues, "there is a potential there, always, that it can do it again".[315] Vicken Cheterian says that genocide denial "pollutes the political culture of entire societies, where violence and threats become part of a political exercise degrading basic rights and democratic practice".[316] When recognizing the Armenian genocide in April 2015, Pope Francis added, "concealing or denying evil is like allowing a wound to keep bleeding without bandaging it".[317]

Denial has also affected Armenians, particularly those who live in Turkey. Historian Talin Suciyan states that the Armenian genocide and its denial "led to a series of other policies that perpetuated the process by liquidating their properties, silencing and marginalising the survivors, and normalising all forms of violence against them".[318] According to an article in the Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, "[d]enial prevents healing of the wounds inflicted by genocide, and constitutes an attack on the collective identity and national cultural continuity of the victimized people".[319] Göçek argues "the lack of acknowledgement literally prevents the wounds opened by past violence to ever heal".[320] The activities of Armenian militant groups in the 1970s and 1980s, like the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia and the Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide, was caused partly by the failure of peaceful efforts to elicit Turkish acknowledgement of the genocide.[321][322] Some historians, such as Stefan Ihrig, have argued that impunity for the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide, as well as silence or justification from bystanders of the crime, emboldened the perpetrators of the Holocaust.[323][202]

International relations

Turkey closed its border with Armenia in 1993, following the First Nagorno-Karabakh War between Armenia and Turkic-speaking Azerbaijan. The closed border harms the economies of Armenia and eastern Turkey.[191][325] Although Armenia was willing to normalize relations without preconditions, Turkey demanded that the Armenian side abandon all support for the recognition efforts of the Armenian diaspora.[326] There have been two major attempts at Turkish-Armenian reconciliation—the Turkish Armenian Reconciliation Commission (2000–2004) and the Zurich Protocols (2009)—both of which failed partly because of the controversy over the Armenian genocide. In both cases, the mediators did their best to sideline historical disputes, which proved impossible.[327] Armenian diaspora groups opposed both initiatives and especially a historical commission to investigate what they considered established facts.[328] Bloxham asserts that since "denial has always been accompanied by rhetoric of Armenian treachery, aggression, criminality, and territorial ambition, it actually enunciates an ongoing if latent threat of Turkish 'revenge'."[329]

Since the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Azerbaijan has adopted Turkey's genocide denial and worked to promote it internationally.[330][331] The Armenian genocide is also widely denied by Azerbaijani civil society.[332] Many Armenians saw a connection between the genocide and later anti-Armenian violence like the 1988 Sumgait pogrom, though the connection between the Karabakh conflict and the Armenian genocide is mostly made by Azerbaijani elites.[333] Azerbaijani nationalists accused Armenians of staging the Sumgait pogrom and other anti-Armenian pogroms, similar to the Turkish discourse on the Armenian genocide.[334]

Azerbaijan state propaganda claims that the Armenians have perpetrated a genocide against Azeris over two centuries, a genocide that includes the Treaty of Gulistan (1813), the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Baku Commune, the January 1990 deployment of Soviet troops to Baku (following the massacres of Armenians in Baku), and especially the 1992 Khojali massacre. According to this propaganda, Armenians committed "the real genocide" and are accused of killing or deporting as many as 2 million Azeris throughout this period.[332][335][336] Following Azerbaijan, Turkey and the Turkish diaspora have lobbied for recognition of the Khojali massacre as a genocide to downplay the Armenian genocide.[337] Azerbaijan sees any country that recognizes the Armenian genocide as an enemy and has even threatened sanctions.[338] Cheterian argues that the "unresolved historic legacy of the 1915 genocide" helped cause the Karabakh conflict and prevent its resolution, while "the ultimate crime itself continues to serve simultaneously as a model and as a threat, as well as a source of existential fear".[333]

References

Citations

- ^ a b

- Marchand, Laure; Perrier, Guillaume (2015). Turkey and the Armenian Ghost: On the Trail of the Genocide. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-7735-9720-4.

The Iğdır genocide monument is the ultimate caricature of the Turkish government's policy of denying the 1915 genocide by rewriting history and transforming victims into guilty parties.

- Hovannisian 2001, p. 803. "... the unbending attitude of the Ankara government, in 1995 of a multi-volume work of the prime ministry's state archives titled Armenian Atrocities in the Caucasus and Anatolia According to Archival Documents. The purpose of the publication is not only to reiterate all previous denials but also to demonstrate that it was in fact the Turkish people who were the victims of a genocide perpetrated by the Armenians."

- Cheterian 2015, pp. 65–66. "Some of the proponents of this official narrative have even gone so far as to claim that the Armenians were the real aggressors, and that Muslim losses were greater than those of the Armenians."

- Gürpınar 2016, p. 234. "Maintaining that 'the best defence is a good offence', the new strategy involved accusing Armenians in response for perpetrating genocide against the Turks. The violence committed by the Armenian committees under the Russian occupation of Eastern Anatolia and massacring of tens of thousands of Muslims (Turks and Kurds) in revenge killings in 1916–17 was extravagantly displayed, magnified and decontextualized."

- Marchand, Laure; Perrier, Guillaume (2015). Turkey and the Armenian Ghost: On the Trail of the Genocide. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-7735-9720-4.

- ^ a b c Dadrian 2003, pp. 270–271; Chorbajian 2016, p. 168;

- Ihrig 2016, pp. 10–11. "While some have gone to great lengths to 'prove" that similar American reports are not credible, especially the memoirs of American ambassador Henry Morgenthau Sr., and allege that, of course, the Entente countries produced only war propaganda, nothing of the sort can be said about the German sources ... After all, they were already afraid of the very negative repercussions these events would have for Germany during and after the war. What reason could they possibly have had to forge such potentially self-incriminating reports, almost on a daily basis, for months?"

- Gürpınar 2016, p. 234. "Contrary to the 'selected naivety' of the first part of the 'Turkish thesis', here, a 'deliberate ignorance' is essential. Armenian 'counter-evidence' such as highly comprehensive and also poignant consular reports and dispatches are to be omitted and dismissed as sheer propaganda without responding to the question of why the diplomats falsified the truth."

- Cheterian 2018a, p. 189. "As the deportations and the massacres were taking place, representatives of global powers, diplomats, scholars, and eyewitnesses were also documenting them, and all parties knew that those events were organized by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) with the aim to exterminate Ottoman Armenians ..."

- ^ a b Academic consensus:

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). "Determinants of the Armenian Genocide". Looking Backward, Moving Forward. Routledge. pp. 23–50. doi:10.4324/9780203786994-3. ISBN 978-0-203-78699-4.

Despite growing scholarly consensus on the fact of the Armenian Genocide ...

- Suny 2009, p. 935. "Overwhelmingly, since 2000, publications by non-Armenian academic historians, political scientists, and sociologists ... have seen 1915 as one of the classic cases of ethnic cleansing and genocide. And, even more significantly, they have been joined by a number of scholars in Turkey or of Turkish ancestry ..."

- Göçek 2015, p. 1. "The Western scholarly community is almost in full agreement that what happened to the forcefully deported Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire in 1915 was genocide ..."

- Smith 2015, p. 5. "Virtually all American scholars recognize the [Armenian] genocide ..."

- Laycock, Jo (2016). "The Great Catastrophe". Patterns of Prejudice. 50 (3): 311–313. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2016.1195548.

... important developments in the historical research on the genocide over the last fifteen years ... have left no room for doubt that the treatment of the Ottoman Armenians constituted genocide according to the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.

- Kasbarian, Sossie; Öktem, Kerem (2016). "One Hundred Years Later: the Personal, the Political and the Historical in Four New Books on the Armenian Genocide". Caucasus Survey. 4 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/23761199.2015.1129787.

... the denialist position has been largely discredited in the international academy. Recent scholarship has overwhelmingly validated the Armenian Genocide ...

- "Taner Akçam: Türkiye'nin, soykırım konusunda her bakımdan izole olduğunu söyleyebiliriz". CivilNet (in Turkish). 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). "Determinants of the Armenian Genocide". Looking Backward, Moving Forward. Routledge. pp. 23–50. doi:10.4324/9780203786994-3. ISBN 978-0-203-78699-4.

- ^ a b Suny 2015, pp. xii–xiii. "The Turkish state and those few historians who reject the notion of genocide have argued that the tragedy was the result of a reasonable and understandable response of a government to a rebellious and seditious population in time of war and mortal danger to the state's survival ... There was no genocide, and the Armenians were to blame for it. They were rebellious, seditious subjects who presented a danger to the empire and got what they deserved ... Still—the denialists claim—despite the existential threat posed by the Armenians and their Russian allies to the survival of the empire, there was no intention or effort by the Young Turk regime to eliminate the Armenians as a people."

- ^ a b c Foundational violence:

- Bloxham 2005, p. 111. "The Armenian genocide provided the emblematic and central violence of Ottoman Turkey's transition into a modernizing nation state. The genocide and accompanying expropriations were intrinsic to the development of the Turkish Republic in the form in which it appeared in 1924."

- Kévorkian 2011, p. 810. "This chapter of the history treated here [the trials] clearly illustrates the incapacity of the great majority to consider these acts punishable crimes; it confronts us with a self-justifying discourse that persists in our own day, a kind of denial of the "original sin," the act that gave birth to the Turkish nation, regenerated and re-centered in a purified space."

- Göçek 2015, p. 19. "... what makes 1915–17 genocidal both then and since is, I argue, closely connected to its being a foundational violence in the constitution of the Turkish republic ... the independence of Turkey emerged in direct opposition to the possible independence of Armenia; such coeval origins eliminated the possibility of acknowledging the past violence that had taken place only a couple years earlier on the one hand, and instead nurtured the tendency to systemically remove traces of Armenian existence on the other."

- Suny 2015, pp. 349, 365. "The Armenian Genocide was a central event in the last stages of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the foundational crime that along with the ethnic cleansing and population exchanges of the Anatolian Greeks made possible the formation of an ethnonational Turkish republic ... The connection between ethnic cleansing or genocide and the legitimacy of the national state underlies the desperate efforts to deny or distort the history of the nation and the state's genesis."

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas; Öktem, Kerem; Reinkowski, Maurus (2015). "Introduction". World War I and the End of the Ottomans: From the Balkan Wars to the Armenian Genocide. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85772-744-2.

We are of the firm opinion, strengthened by the contributions in this volume, that the single most important reason for this inability to accept culpability is the centrality of the Armenian massacres for the formation of the Turkish nation-state. The deeper collective psychology within which this sentiment rests assumes that any move toward acknowledging culpability will put the very foundations of the Turkish nation-state at risk and will lead to its steady demise.

- Chorbajian 2016, p. 169. "As this applies to the Armenians, their physical extermination, violent assimilation, and erasure from memory represent a significant continuity in the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey. The planning and implementation of the Armenian Genocide as an act of commission (1915–22) and omission (1923–present) constitute the final act of the Ottoman Empire and the start of a process of Turkification that defines the Turkish Republic a century later."

- ^ a b Distinctiveness of Turkish denial efforts:

- Smith, Roger W. (2006). "The Significance of the Armenian Genocide after Ninety Years". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 1 (2): i–iv. doi:10.3138/G614-6623-M16G-3648.

The Armenian Genocide, in fact, illuminates with special clarity the dangers inherent in the political manipulation of truth through distortion, denial, intimidation, and economic blackmail. In no other instance has a government gone to such extreme lengths to deny that a massive genocide took place.

- Avedian 2013, p. 79. "Nonetheless, if there is one aspect which makes the Armenian case to stand out, if not unique, is its denial. The Armenian genocide is by far the case which is systematically and officially denied by a state ..."

- Akçam 2018, pp. 2–3. "Turkish denialism in regard to the events of the First World War is perhaps the most successful example of how the well-organized, deliberate, and systematic spreading of falsehoods can play an important role in the field of public debate ... If every case of genocide can be understood as possessing its own unique character, then the Armenian case is unique among genocides in the long-standing efforts to deny its historicity, and to thereby hide the truths surrounding it."

- Tatz, Colin (2018). "Why is the Armenian Genocide not as well known?". In Bartrop, Paul R. (ed.). Modern Genocide: Analyzing the Controversies and Issues. ABC-CLIO. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4408-6468-1.

Uniquely, the entire apparatus of a nation-state has been put to work to amend, ameliorate, deflect, defuse, deny, equivocate, justify, obfuscate, or simply omit the events. No other nation in history has so aggressively sought the suppression of a slice of its history, threatening everything from breaking off diplomatic or trade relations, to closure of air bases, to removal of entries on the subject in international encyclopedias.

- Smith, Roger W. (2006). "The Significance of the Armenian Genocide after Ninety Years". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 1 (2): i–iv. doi:10.3138/G614-6623-M16G-3648.

- ^ a b Demirel & Eriksson 2020, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Only 9 Percent of Turks say Armenian Killings Genocide: Poll". The Daily Star. AFP. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Maranci, Christina (2002). "The Art and Architecture of Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush". In Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.). Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Mazda Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-1-56859-136-0.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press. pp. 3, 30. ISBN 978-0-253-20773-9.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. xiv.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 26–27, 43–44.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 105.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 11, 71.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 129, 170–171.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 204, 206.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 127–129, 133, 170–171.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 62, 150.

- ^ a b Maksudyan, Nazan (2019). ""This Is a Man's World?": On Fathers and Architects". Journal of Genocide Research. 21 (4): 540–544 [542]. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1613816. ISSN 1462-3528.

Turkish nationalists were following the pattern that was firmly established after the Hamidian massacres, though new research might take the chronology of unpunished crimes and denial further back to the first half of the nineteenth century. In each and every case of violence against the non-Muslims, the first reaction of the state – even though the regime changed, along with the involved actors – was denial.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 154–155, 189.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 185.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 218.

- ^ a b Suny 2015, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Dadrian 2003, p. 277.

- ^ Kaligian 2014, p. 217.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 236.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 225.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 244–245. "Any incident of Armenian resistance, any discovery of a cache of arms, was transformed into a vision of a coordinated widespread Armenian insurrection ... Deportations ostensibly taken for military reasons rapidly radicalized monstrously into an opportunity to rid Anatolia once and for all of those peoples perceived to be an imminent existential threat to the future of the empire."

- ^ Akçam 2018, p. 158.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2019). "When Was the Decision to Annihilate the Armenians Taken?". Journal of Genocide Research. 21 (4): 457–480 [457]. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1630893.

Most scholars placed the possible date(s) for a final decision at the end of March (or beginning of April).

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Ihrig 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Dadrian 2003, p. 274.

- ^ Kaiser, Hilmar (2010). "Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

The Armenian deportations were not the result of an Armenian rebellion. On the contrary, Armenians were deported when no danger of outside interference existed. Thus Armenians near front lines were often slaughtered on the spot and not deported. The deportations were not a security measure against rebellions but depended on their absence.

- ^ Suny 2009, p. 945. "A newly minted doctor of history, Fuat Dündar, showed with his careful reading of Ottoman archival documents how the deportations had been organized and carried out by the Turkish authorities, and—most shocking of all—that Minister of the Interior Talat, the chief initiator, had been aware that sending people to the Syrian desert outpost of Der Zor meant certain death."

Dadrian 2003, p. 275. "As diplomat after diplomat from allied Germany and Austria (as well as American Ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau) repeatedly averred, by dispatching the victim population to these deserts the Turks were dispatching them to death and ruination. Even the Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Fourth Army in control of these areas in his memoirs debunked and ridiculed the pretense of 'relocation.'" - ^ Dadrian & Akçam 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. p. 486. ISBN 978-0-674-91645-6.

- ^ Ekmekçioğlu 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Akçam 2012, pp. 289–290, 331.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. 341. "On the basis of existing Interior Ministry Papers from the period, it can confidently be asserted that the goal of the CUP was not the resettlement of Anatolia's Armenian population and their just compensation for the property and possessions that they were forced to leave behind. Rather, the confiscation and subsequent use of Armenian property clearly demonstrated that Unionist government policy was intended to completely deprive the Armenians of all possibility of continued existence."

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 250. "This false equation of the Armenian violence with the Turkish one whitewashed the disparity between two sufferings, conveniently overlooking two factors. The two sufferings were much different in scale; the violence the Muslims suffered in the east led to the deaths of at most 60,000 Muslims, yet the collective violence the CUP perpetrated led to the deaths of at least 800,000 Armenians."

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 814 fn. 102.

- ^ de Waal 2015, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Cheterian 2018a, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Definitions of denial:

- Hovannisian 2015, p. 244. "This essay follows the general usage of the term denial to mean assertions that an event understood as genocide (typically founded on extensive analysis of evidence by reputable experts) is in fact not genocide, whether by representing the events as something else or claiming that the core events in question did not occur at all."

- Smith 2015, p. 6. "In many ways, the Turkish arguments have remained the same: denial of the facts, of responsibility, of the significance of what took place, and that the term genocide applies ... the goal of denial is to create a new reality (denial as construction) with both "sides" engaged in an unending debate in which a consensus will never arrive and for which there will be a need for unending research to establish the facts."

- Göçek 2015, p. 13. "The denial ultimately includes and excludes certain elements to create a semblance of the truth; indeed, this quality of "half-truth" makes denial rigorous. The half-truth highlights the elements that favor the interests of the perpetrators while silencing, dismissing, or subverting those factors that undermine perpetrator interests by revealing clues leading to the inherent collective violence."

- Ihrig 2016, p. 12. "Denialism here denotes an approach that rejects the charge of genocide (against the Young Turks), mostly by denying intent and minimizing the extent of the atrocities."

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 63. "... even though their intent all along had been destruction, [the Young Turks] presented it to the public as Armenian "migration" to safe places. This constituted the most egregious Young Turk denial."

Hovannisian 2015, p. 229. "It may be inaccurate to say that denial is the last phase of genocide, as has been posited by Israel Charny and others, including this writer himself, for denial has been present from the very outset, even as the process was initiated and carried forward toward the desired end."

Akçam 2018, p. 3. "... the denial of the Armenian Genocide began not in the wake of the massacres but was an intrinsic part of the plan itself. The deporting of the Armenians from their homeland to the Syrian deserts and their elimination, both on the route and at their final destinations, were performed under the guise of a decision to resettle them."

Cheterian 2018a, p. 195. "Ottoman Turks exterminated their victims in secret. They pretended to displace them from warzones for their own safety, and great care was taken to communicate orders of massacres in secretive, coded messages. Oblivion begins there, an intrinsic part of the crime itself."

Bloxham 2005, p. 111; Avedian 2013, p. 79. - ^ a b Mamigonian 2015, pp. 61–62. "Denial of the Armenian Genocide began concurrently with and was a part of the Committee of Union and Progress's (CUP) execution of it. As the Ottoman Armenian population was massacred and deported, the Ottoman leadership constructed a narrative that, subjected to occasional revisions and refinements, remains in place today ..."

- ^ Akçam 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Dundar, Fuat (2010). Crime of Numbers: The Role of Statistics in the Armenian Question (1878–1918). Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-351-52503-9.

- ^ a b Chorbajian 2016, p. 170.

- ^ Chorbajian 2016, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Varnava, Andrekos (2016). "Book Review: Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence against the Armenians, 1789–2009". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 10 (1): 121–123. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.10.1.1403. ISSN 1911-0359.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 2015, p. 229.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b Kévorkian 2011, p. 810.

- ^ Akçam 2012, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 813.

- ^ Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2008). "Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk 'Social Engineering'". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (7). doi:10.4000/ejts.2583. ISSN 1773-0546.

- ^ Zürcher 2011, p. 308. "In ideological terms there is thus a great deal of continuity between the periods of 1912–1918 and 1918–1923. This should come as no surprise ... the cadres of the national resistance movement almost without exception consisted of former Unionists, who had been shaped by their shared experience of the previous decade."

- ^ a b Zürcher 2011, p. 316. "Many of the people in central positions of power (Şükrü Kaya, Kazım Özalp, Abdülhalik Renda, Kılıç Ali) had been personally involved in the massacres, but besides that, the ruling elite as a whole depended on a coalition with provincial notables, landlords, and tribal chiefs, who had profited immensely from the departure of the Armenians and the Greeks. It was what Fatma Müge Göçek has called an unspoken "devil's bargain." A serious attempt to distance the republic from the genocide could have destabilized the ruling coalition on which the state depended for its stability."

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 806; Cheterian 2015, p. 155; Baer 2020, p. 83; Dixon 2010a, p. 468. "Many contemporary scholars emphasise that this official narrative [on the Armenian Genocide] is largely shaped by continuities and constraints inherited from the founding of the Republic. In particular, they highlight the striking continuities among political elites from the Young Turk through the Republican periods, the concentrated interests of a small group of business and political elites whose wealth can be traced back to confiscated Armenian assets, and the homogenising and Turkifying nature of Turkish national identity."

- ^ Kieser 2018, pp. 385–386.

- ^ a b Ekmekçioğlu 2016, p. 7. "Even though the putative mass Armenian "betrayal" happened after the Young Turks acted on their plan to eradicate Armenianness, Turkish nationalist narratives have used Armenians' 'collaboration with the enemy' and secessionist agenda during the postwar occupation years as a justification for the 1915 'deportations'."

- ^ Ulgen 2010, pp. 376–377.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Bloxham 2005, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (1999). "Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal". In Charny, Israel W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide: A–H. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-87436-928-1.

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 818.

- ^ Kieser 2018, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 810–811.

- ^ Göçek 2011, pp. 45–46. "First, none of these works, originally penned around the time of the events of 1915, question the occurrence of the Armenian "massacres" ("genocide" did not yet exist as a term) ... The later ones, increasingly imbued with protonationalist sentiments, view the committed crimes as a duty necessary for the establishment and preservation of a Turkish fatherland."

- ^ a b Avedian 2012, p. 816.

- ^ Ulgen 2010, pp. 378–380.

- ^ Ulgen 2010, p. 371.

- ^ Baer 2020, p. 79.

- ^ Zürcher 2011, p. 312.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 419.

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 267.

- ^ Aybak 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. xi.

- ^ Hofmann, Tessa (2016). "Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks, and a Century of Genocide by Vicken Cheterian". Histoire sociale/Social history. 49 (100): 662–664. doi:10.1353/his.2016.0046.

The foundation of the Turkish republic and the CUP's genocide perpetrators are to this day commemorated with pride. Mosques, schools and kindergartens, boulevards and public squares in Turkey continue to bear the name of high ranking perpetrators.

Kieser 2018, p. xii. "[Talat Pasha's] legacy is present in powerful patterns of government and political thought, as well as in the name of many streets, schools, and mosques dedicated to him in and outside Turkey ... In the eyes of his admirers in Turkey today, and throughout the twentieth century, he was a great statesman, skillful revolutionary, and farsighted founding father ..."

Avedian 2012, p. 816. "Talaat and Cemal, both sentenced to the death in absentia for their key involvement in the Armenian massacres and war crimes, were given posthumous state burials in Turkey, and were elevated to the rank of national heroes." - ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 811.

- ^ Arango, Tim (16 April 2015). "A Century After Armenian Genocide, Turkey's Denial Only Deepens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Gürpınar 2013, p. 420. "... the official narrative on the Armenian massacres constituted one of the principal pillars of the regime of truth of the Turkish state. Culpability for these massacres would incur enormous moral liability; tarnish the self-styled claim to national innocence, benevolence and self-reputation of the Turkish state and the Turkish people; and blemish the course of Turkish history. Apparently, this would also be tantamount to casting doubt on the credibility of the foundational axioms of Kemalism and the Turkish nation-state."

- ^ Bilali 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, p. 106.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, p. 107.

- ^ a b Akçam 2012, p. xii.

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 799.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. xi. "'National security' not only explained and justified the traumatic events of the past but would also support the construction of genocide denial in the future. Thereafter, an open and frank discussion of history would be perceived as a subversive act aimed at partitioning the state. Well into the new millennium, Turkish citizens who demanded an honest historical accounting were still being treated as national security risks, branded as traitors to the homeland or dupes of hostile foreign powers, and targeted with threats."

- ^ Gürpınar 2016, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Dixon, Jennifer M. (2018). Dark Pasts: Changing the State's Story in Turkey and Japan. Cornell University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-5017-3025-2.

- ^ Akçam 2018, p. 157.

- ^ Demirdjian 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Zürcher 2011, p. 316.

- ^ a b Chorbajian 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Cheterian 2015, p. 65.

- ^ Akçam 2012, pp. 54–55; Cheterian 2015, pp. 64–65; Chorbajian 2016, p. 174; MacDonald 2008, p. 121.

- ^ Üngör 2014, pp. 165–166.

- ^ de Waal 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Akçam 2018, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Dixon 2010a, p. 473.

- ^ Cheterian 2018a, p. 205.

- ^ Auron 2003, p. 259.

- ^ Dixon 2010a, pp. 473–474.

- ^ Baer 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Göçek 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Ulgen 2010, pp. 384–386, 390.

- ^ Mamigonian 2015, p. 63.

- ^ Gürpınar 2016, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Baer 2020, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Göçek 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Bayraktar 2015, p. 802.

- ^ Gürpınar 2013, p. 423.

- ^ Galip 2020, p. 153.

- ^ Gürpınar 2013, p. 421.

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 293.

- ^ de Waal 2015, p. 182; Suny 2009, p. 938; Cheterian 2015, pp. 140–141; Gürpınar 2013, p. 419.

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 468.

- ^ Suny 2009, p. 942.

- ^ Bayraktar 2015, pp. 804–805.

- ^ a b Gürpınar 2013, pp. 419–420.

- ^ Gürpınar 2013, pp. 420, 422, 424.

- ^ Erbal 2015, pp. 786–787.

- ^ de Waal 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Freely, Maureen (23 October 2005). "'I Stand by My Words. And Even More, I Stand by My Right to Say Them ...'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 2. "Because of this partial use of sources, the Western scholarly community finds the ensuing Turkish official discourse unscientific, propagandistic, and rhetorical and therefore does not address or engage it."

- ^ Erbal 2015, p. 786.

- ^ Ekmekçioğlu 2016, p. xii.

- ^ a b Göçek 2015, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Kale, Yeliz (2018). "The Opinions of Author Related to Trade Books Published for Students in History Teaching". Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi. 7 (3). ISSN 2147-0626.

- ^ Some private schools and to a lesser extent some state schools also use alternative textbooks which are not approved by Ministry of Education.[137]

- ^ Dixon 2010b, p. 105.

- ^ Aybak 2016, p. 13. "This officially distributed educational material reconstructs the history in line with the denial policies of the government portraying the Armenians as backstabbers and betrayers, who are portrayed as a threat to the sovereignty and identity of modern Turkey. The demonization of the Armenians in Turkish education is a prevailing occurrence that is underwritten by the government to reinforce the denial discourse."

- ^ Galip 2020, p. 186. "Additionally, for instance, the racism and language of hatred in officially approved school textbooks is very intense. These books still show Armenians as the enemies, so it would be necessary for these books to be amended ..."

- ^ Cheterian 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b Gürpınar 2016, p. 234.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, p. 104.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, pp. 104, 116–117.

- ^ Bilali 2013, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Dixon 2010b, p. 115.

- ^ Bilali 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 4, 10.