Archaeopteris

| Archaeopteris Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Archaeopteris hibernica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Class: | †Progymnospermopsida |

| Order: | †Archaeopteridales |

| Family: | †Archaeopteridaceae |

| Genus: | †Archaeopteris Dawson (1871) |

| Species | |

| |

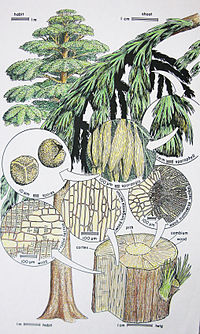

Archaeopteris is an extinct genus of progymnosperm tree with fern-like leaves. A useful index fossil, this tree is found in strata dating from the Upper Devonian to Lower Carboniferous (383 to 323 million years ago), the oldest fossils being 385 million years old,[1] and had global distribution.

Until the 2007 discovery of Wattieza, many scientists considered Archaeopteris to be the earliest known tree. Bearing buds, reinforced branch joints, and branched trunks similar to today's woody plants, it is more reminiscent of modern seed-bearing trees than other spore-bearing taxa. It combines characteristics of woody trees and herbaceous ferns, and belongs to the progymnosperms, a group of extinct plants more closely related to seed plants than to ferns, but unlike seed plants, reproducing using spores like ferns.

Taxonomy

John William Dawson described the genus in 1871. The name derives from the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaīos, "ancient"), and πτέρις (ptéris, "fern"). Archaeopteris was originally classified as a fern, and it remained classified so for over 100 years. In 1911, Russian paleontologist Mikhail Dimitrievich Zalessky described a new type of petrified wood from the Donets Basin in modern Ukraine. He called the wood Callixylon, though he did not find any structures other than the trunk. The similarity to conifer wood was recognized. It was also noted that ferns of the genus Archaeopteris were often found associated with fossils of Callixylon.

In the 1960s, paleontologist Charles B. Beck was able to demonstrate that the fossil wood known as Callixylon and the leaves known as Archaeopteris were actually part of the same plant.[2][3] It was a plant with a mixture of characteristics not seen in any living plant, a link between true gymnosperms and ferns.

The genus Archaeopteris is placed in the order Archaeopteridales and family Archaeopteridaceae. The name is similar to that of the first known feathered bird, Archaeopteryx, but in this case refers to the fern-like nature of the plant's fronds.

Relationship to spermatophytes

Archaeopteris is a member of a group of free-sporing woody plants called the progymnosperms that are interpreted as distant ancestors of the gymnosperms. Archaeopteris reproduced by releasing spores rather than by producing seeds, but some of the species, such as Archaeopteris halliana were heterosporous, producing two types of spores. This is thought to represent an early step in the evolution of vascular plants towards reproduction by seeds,[4] which first appeared in the earliest, long-extinct gymnosperm group, the seed ferns (Pteridospermatophyta). The conifers or Pinophyta are one of four divisions of extant gymnosperms that arose from the seed ferns during the Carboniferous period.

Description

- A. halliana

- H. maclienta

- A. notosaria

The trees of this genus typically grew to 24 m (80 ft) in height[5] with leafy foliage reminiscent of some conifers. The large fern-like fronds were thickly set with fan-shaped leaflets or pinnae. The trunks of some species exceeded 1.5 m (5 ft) in diameter. The branches were borne in spiral arrangement, and a forked stipule was present at the base of each branch.[5] Within a branch, leafy shoots were in opposite arrangement in a single plane. On fertile branches, some of the leaves were replaced by sporangia (spore capsules).

Other modern adaptations

Aside from its woody trunk, Archaeopteris possessed other modern adaptations to light interception and perhaps to seasonality as well. The large umbrella of fronds seems to have been quite optimized for light interception at the canopy level. In some species, the pinnules were shaped and oriented to avoid shading one another. There is evidence[citation needed] that whole fronds were shed together as single units, perhaps seasonally like modern deciduous foliage or like trees in the cypress family Cupressaceae.

The plant had nodal zones that would have been important sites for the subsequent development of lateral roots and branches. Some branches were latent and adventitious, similar to those produced by living trees that eventually develop into roots. Before this time, shallow, rhizomatous roots had been the norm, but with Archaeopteris, deeper root systems were being developed that could support ever higher growth.

Habitat

Evidence indicates that Archaeopteris preferred wet soils, growing close to river systems and in floodplain woodlands. It would have formed a significant part of the canopy vegetation of early forests. Speaking of the first appearance of Archaeopteris on the world-scene, Stephen Scheckler, a professor of biology and geological sciences at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, says, "When [Archaeopteris] appears, it very quickly became the dominant tree all over the Earth. On all of the land areas that were habitable, they all had this tree".[6] One species, Archaeopteris notosaria, has even been reported from within what was then the Antarctic Circle: leaves and fertile structures were identified from the Waterloo Farm lagerstätte in what is now South Africa.[7]

Scheckler believes that Archaeopteris had a major role in transforming its environment. "Its litter fed the streams and was a major factor in the evolution of freshwater fishes, whose numbers and varieties exploded in that time, and influenced the evolution of other marine ecosystems. It was the first plant to produce an extensive root system, so had a profound impact on soil chemistry. And once these ecosystem changes happened, they were changed for all time. It was a one-time thing."[8]

Looking roughly like a top-heavy Christmas tree, Archaeopteris may have played a part in the transformation of Earth's climate during the Devonian before becoming extinct within a short period of time at the beginning of the Carboniferous period.

See also

References

- ^ Fossilized Roots Are Revealing the Nature of 385-Million-Year-Old Forests

- ^ Beck, CB (1960). "The identity of Archaeopteris and Callixylon". Brittonia. 12 (4): 351–368. Bibcode:1960Britt..12..351B. doi:10.2307/2805124. JSTOR 2805124. S2CID 27887887.

- ^ Beck, CB (1962). "Reconstruction of Archaeopteris and further consideration of its phylogenetic position" (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 49 (4): 373–382. doi:10.2307/2439077. hdl:2027.42/141981. JSTOR 2439077.

- ^ Bateman, R.M.; W.A. Dimichele (1994). "Heterospory - the most iterative key innovation in the evolutionary history of the plant kingdom" (PDF). Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 69 (3): 345–417. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1994.tb01276.x. S2CID 29709953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ a b Beck, C. (1962). "Reconstructions of Archaeopteris, and further consideration of its phylogenetic position". American Journal of Botany. 49 (4): 373–382. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1962.tb14953.x. hdl:2027.42/141981. JSTOR 2439077.

- ^ Nix, Steve. "Archaeopteris - The First "True" Tree". Forestry.about.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ Anderson, H. M., Hiller, N. and Gess, R. W.(1995). Archaeopteris (Progymnospermopsida) from the Devonian of southern Africa. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 117, 305–320.

- ^ Virginia Tech, "Earliest Modern Tree Lived 360-345 Million Years Ago," ScienceDaily, 22 April 1999

External links

- History of Paleozoic Forests: the Early Forests and the Progymnosperms

- Consequences of Rapid Expansion of Late Devonian Forests, by Stephen E. Scheckler Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Walker, Cyril and David Ward. Fossils. Smithsonian Handbooks. Dorling Kindersley, Inc. New York, NY (2002).

- Mayr, Helmut. A Guide to Fossils. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ (1992).

- Introduction to the Progymnosperms

- Davis, Paul and Kenrick, Paul; Fossil Plants. Smithsonian Books (in association with the Natural History Museum of London), Washington, D.C. (2004). ISBN 1-58834-156-9