Ansar–Khatmiyya rivalry

The Ansar–Khatmiyya rivalry,[1][2][3] also known as al-Mahdi and al-Mirghani rivalry or the Two Sayyids rivalry,[4] was a sectarian division in Sudan that shaped the country's political landscape after the end of the Mahdist State in 1899 and until the Kizan era in 1989.

The rivalry between the Ansar and Khatmiyya sects in Sudan dates back to the 19th century under Turco-Egyptian rule, which saw the rise of politically driven religious movements in Sudan. The Ansar, followers of Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, established the Mahdist State in 1885, which was later overthrown in 1899 by Anglo-Egyptian forces. Meanwhile, the Khatmiyya sect, founded by Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim in 1817, maintained close ties with Egyptian rulers and received colonial support.

During Sudan’s colonial period, the British used both groups to manage the country, but tensions arose due to their differing visions for Sudan’s future. The Ansar, led by Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi, advocated for "Sudan for the Sudanese" and independence, while the Khatmiyya, led by Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, supported unity with Egypt under the "Unity of the Nile Valley" slogan. These divisions deepened during Sudan's independence movement, with the Ansar aligning with the Umma Party and the Khatmiyya backing the National Unionist Party (NUP), later the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

Post-independence, their rivalry shaped Sudan's political landscape, contributing to political instability, coups, and factionalism. Both groups faced suppression during authoritarian regimes, especially under Gaafar Nimeiry and Omar al-Bashir. In modern times, their influence has waned, with divisions within their political wings limiting their role in Sudanese politics.

History

Ansar and Khatmiyya inception

Under the Turco-Egyptian rule, Sudan saw the rise of politically driven religious movements. This was highlighted by the Mahdist Uprising in 1843, led by Muhammad Ahmad "al-Mahdi" against the Turco-Egyptian rule. After liberating Khartoum and killing General Charles Gordon, the Mahdist state was established in 1885. Despite its defeat by British forces in 1899, the movement's influence persisted with its followers known as "Ansar."[5] Ansar were based in Aba Island, and were popular in Darfur (western part of Sudan).

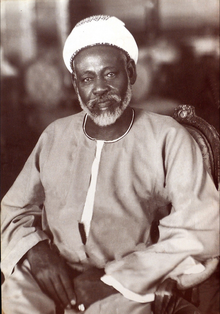

In 1899, after the fall of the Mahdist State the British government placed restrictions on the movements and activity of the Mahdi's son, Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi. However, he soon emerged as the leader of the Ansar. Throughout most of the colonial era of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, the British government considered him important as a moderate leader of the Mahdists.[6]

In the early 1920s, from 5,000–15,000 pilgrims were coming to Aba Island each year to celebrate Ramadan. Many of them identified Abd al-Rahman with the prophet Isa, the Islamic interpretation of Jesus and assumed that he would drive the white Christian colonists out of Sudan. The British government found that Abd al-Rahman was in correspondence with agents and leaders in Nigeria and Cameroon, predicting the eventual victory of the Mahdists over the Christians. They blamed him for unrest in these colonies. After pilgrims from West Africa held mass demonstrations on Aba Island in 1924, the Sayyid was told to put a stop to the pilgrimages.[7]

Conversely, during the Turco-Egyptian rule in Sudan, the "Khatmiyya," established by Muhammad Othman al-Mirghani al-Khitmi in 1817, received support and annual endowment from the Turco-Egyptian and British-Egyptian governments.[5] Khatmiyya were based in Kassala, and were popular in the eastern part of Sudan with close ties to Egypt.[4]

Both the Khatmiyya and Ansar received honorary titles and support from the British administration, however, the Ansar leaders resented the Khatmiyya being part of the political landscape in Sudan. Khatmiyya warned that this resentment might lead to civil war.[4]

The struggle for Sudan's independence

Following the creation of Graduates' Club, which opened its doors in Omdurman on 18 May 1918 under the supervision of the Gordon Memorial College, politically inclined members sought to expand its role into a platform for nationalist discourse and resistance against the Anglo-Egyptian colonial rule. Discussions at the club often centred on Sudan's political future, fostering debates that eventually led to the formation of two ideological factions with distinct visions for Sudan's path to independence.[8]

The first faction promoted the idea of "Sudan for the Sudanese," inspired by journalist Hussein Sharif. Sharif, through his writings in the newspaper Hadarat Al-Sudan, advocated limited cooperation with the British to modernise Sudan but opposed unity with Egypt, fearing it would undermine Sudanese autonomy. This group, closely allied with Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi of the Ansar sect, dominated the club's leadership from 1920 to 1933.[8][9] For this faction, the Mahdi was portrayed as the first Sudanese nationalist and Abd al-Rahman was to many an attractive leader of the independence movement.[10]

The second faction promoted the idea of "Unity of the Nile Valley" which was supported unity with Egypt under the Egyptian crown, emphasising cultural and geographical ties between the two nations. Led by Ahmed al-Feel, they rejected alliances with religious sects, despite many members being from families traditionally loyal to the Khatmiyyah sect,[8][9] and its leader Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani.[11][12]

The Graduates' General Congress (GGC) was established on 12 February 1938, with 1,180 graduates approving its constitution and electing a 15-member executive committee.[13] Aimed at advocating for Sudanese welfare and independence, the GGC used rallies, media, and alliances to mobilize public support. In 1942, it submitted demands for self-determination and the repeal of restrictive policies, but these were rejected by the colonial government, which denied the Congress political legitimacy. This rejection caused internal divisions between moderates, who sought cooperation, and assertive figures like Ismail al-Azhari, who pushed for politicisation. Al-Azhari's leadership shifted the GGC's focus to broader nationalist goals.[14]

Al-Azhari's influence culminated in the formation of the Ashiqqa (Brothers) party in 1943,[14] advocating for Sudan's autonomy within a united structure with Egypt, which later became the "National Unionist Party (NUP)" in 1952.[5] Al-Azhari's main support came from the Khatmiyya Sufi order.[15][16] Despite Khatmiyya still receiving an annual British endowment, the British, concerned about Khatmiyyah's growing political influence, have sought to counteract this by bolstering the political position of Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi.[4][5]

In August 1944 Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi met with senior GGC members and tribal leaders to discuss formation of a pro-independence political party that was not associated with Mahdism. In February 1945 the National Umma Party had been organized and the party's first secretary, Abdullah Khalil, applied for a government license. The constitution of the party made no mention of Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi or of the Ansar. The only visible link to Abd al-Rahman was the party's reliance on him for funding.[17]

This division among nationalist factions, compounded by historical and ideological tensions, hindered a unified front. Efforts in 1946 to negotiate a common stance on Sudan's future further exposed these rifts, solidifying separate paths for unity with Egypt and full independence. This fragmentation shaped the trajectory of Sudanese political developments for years to come.[18][19][14]

The pro-Egyptian NUP boycotted the 1948 Legislative Assembly elections. As a result, pro-independence groups dominated the Legislative Assembly. On 19 October 1952, an agreement was reached between Britain and the Umma-dominated legislature and their allies in a collation known as the Sudanese Independence Front that was supported by the British since 1947 to act as bulwark against Egyptian nationalism. This agreement gave the green light for Sudan to achieve self-government by the end of 1952, followed by the exercise of the right to self-determination within the subsequent three years.[20] The legislators then enacted a constitution that provided for a prime minister and council of ministers responsible to a bicameral parliament. The agreement came to be known as the "Gentlemen's Agreement".[21] Later, Colonel Muhammad Naguib, who seized power after the 1952 Egyptian revolution, accepted the right of Sudanese self-determination.

Ismail al-Azhari's pro-Egyptian NUP won the 1953 parliamentary elections and he became the Chief Minister in 1954, he recognized growing public opposition to union with Egypt. In response, al-Azhari shifted the party's stance to support Sudanese independence, advocating for the withdrawal of foreign troops and calling on Egyptian and the British to sponsor a referendum.[22]

After independence (1956–1969)

On 19 December 1955, shortly after the First Sudanese Civil War had broken out, al-Azhari, declared the Independence of Sudan. Internal divisions between the al-Azhari faction and the Khatmiyya order, primary around al-Azhari's secular policies, led to a split in June 1956, with the Khatmiyya order founding the new People's Democratic Party (PDP), under Ali al-Mirghani's leadership. The Umma and the PDP combined in parliament to bring down the Azhari government.[5]

Al-Azhari's NUP lost its majority in the 1958 parliamentary election, and with support from the two parties and backing from the Ansar and the Khatmiyyah, Abdallah Khalil put together a coalition government.[23] However, from its inception in 1956, the Umma-PDP coalition could not reach an agreement on a permanent constitution, stabilising the south, encouraging economic development, and improving relations with Egypt.[22] Khalil grew disillusioned with the democratic process due to factionalism and bribery in parliament, coupled with the government's inability to resolve Sudan's many social, political, and economic problems. On 17 November 1958 - the day parliament was to convene - then simultaneously Prime Minister and Minister of Defence Abdallah Khalil (a retired army officer) orchestrated effectively a self-coup against the collation civilian government, and handing power to General Ibrahim Abboud.[24]

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman died in 1959, and his son, Sadiq al-Mahdi, was imam of the Ansar for the next two years. After his death in 1961, he was succeeded as imam by his brother, Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi,[25] while Al-Siddiq al-Mahdi's son, Sadiq al-Mahdi was elected president of the Umma Party in November 1964.[26] On the other hand, Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani died in 1968, leaving his eldest son, Mohamed Osman al-Mirghani to lead the Khatmiyya and PDP. This was dubbed the "divine leadership" by historians.[27]

Following October 1964 Revolution, a parliamentary election was held in 1965, which was boycotted by the PDP and won by the Umma party, but there was a low turnout.[28] The Umma and al-Azhari's NUP formed a collation government headed by Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub (Umma), whereas al-Azhari became Chairman of the Sovereignty Council.[29][30] However, this coalition collapsed in October 1965 after the two parties failed to agree on control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In July 1966, Prime Minister Mahgoub resigned after a parliamentary vote of censure and was replaced by Sadiq al-Mahdi.[31] Mahgoub resignation was support by Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi, which lead to the split of the Umma party to Umma–Sadiq and Umma–Imam.[28] Sadiq's collation government failed in May 1967 and Mahgoub returned in leading a coalition government.[32]

Al-Azhari and PDP leader Mohamed Osman al-Mirghani reunited in December 1967 in the presence of King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, under the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). However, divisions within the Umma Party and opposition from Sadiq al-Mahdi's faction led to a political crisis. After Mahjub dissolved parliament, rival governments emerged, one inside the parliament and the other outside. The Supreme Court upheld Mahjub's dissolution, and new parliamentary elections were set for April 1968.[22]

The DUP party won the 1968 election and subsequently formed a coalition government with the Umma–Imama faction. In 1968, Sadiq al-Mahdi's Umma faction formed the parliamentary opposition but faced government crackdowns for resisting constitutional efforts. Later that year, the two Umma factions united to support Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi for the presidency, while the DUP backed Al-Azhari as their candidate.[22] However, the government was toppled in the 25 May 1969 coup d'état.

Nimeiry era (1969–1989)

The coup against the was lead by Colonel Gaafar Nimeiry and Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi withdrew to his base in Aba Island.[33] In March 1970 Nimeiry tried to visit the island to talk with the imam, but was prevented by hostile crowds. Fighting later broke out between government forces opposed by up to 30,000 Ansar. Army units backed up by air support assaulted the island, and about 3,000 people were killed.[34]

Sadiq al-Mahdi was arrested in 1970, and for many years alternated between spells in prison in Sudan and periods of exile. Following the coup attempt in June 1976 that was orchestrated by Sadiq al-Mahdi,[35] Gaafar Nimeiry sought "national reconciliation" and integrated Sadiq al-Mahdi into the Sudanese Socialist Union's political bureau, which ruled under one party system.[36]

Between 1977 and 1985, Nimeiry's implemented an "Islamic approach" in Sudan, which aimed to end sectarian divisions, especially the al-Mirghani and al-Mahdi rivalry, and consolidate Islamic governance.[37] Nimeiry declared himself the "imam of the Sudanese umma", and the Hassan al-Turabi (leader of the National Islamic Front) assisted with drafting the laws that came to be known as the September Laws. Sadiq al-Mahdi opposed the laws.[37]

During the same period, Khatmiyya remained largely inactive, with their leaders in-self exile in Egypt, while allowing its members to freely decide on the degree of participation in central and state governments.[38][39][40]

Following the 1985 coup d'état, Sadiq al-Mahdi was again elected president of the Umma party and Khatmiyya and Ansar returned to the political life in Sudan. The Umma and DUP returned to the political landscape in the 1986 election, where the Umma won 100 seats and DUP 63 seats, but al-Turabi's National Islamic Front made substantial gains with 51 seats. Sadiq al-Mahdi became the Prime Minister of Sudan and formed a collation government with the DUP with Ahmed al-Mirghani (Mohamed Osman al-Mirghani's youngest brother) becoming the president.[26]

Sadiq al-Mahdi, who initially opposed the Islamic laws he later supported, envisioned a fully Arabised and Islamised southern Sudan. The collation government was overthrown in the 1989 coup d'état which was led by Colonel Omar al-Bashir and orchestrated by al-Turabi.[37]

Al-Bashir era (1989–1999) and decline

Omar al-Bashir and al-Turabi regime solidified its power using authoritarian tools, establishing a political security apparatus called "Internal Security," led by Colonel Bakri Hassan Saleh. This body was known for its notorious detention facilities, "ghost houses," where intellectuals were detained and tortured. Public freedoms were eroded, and political parties were abolished.[5]

Al-Bashir adopted more radical instance to Islamism by introducing a stricter penal code than the September laws and establishing the "People's Police," akin to Saudi Arabia's Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. In this period, Osama bin Laden moved to Khartoum and welcomed by al-Turabi. Training camps for armed Islamic groups were established in Sudan, and al-Turabi attempted mediation between Hamas and the Palestine Liberation Organization.[5]

Meanwhile, the Khatmiyya and the DUP were banned after the coup,[41] with al-Mirghani was placed under house arrest in November 1989 and was released by February 1990.[42] After that, the Khatmiyya remained largely remained largely inactive, with their leaders in-self exile in Egypt until the 2018 Sudanese revolution and 2019 coup d'état. During that period the DUP participated in the 2010[43] and 2015 general election but received considerably low votes.[44] Following Sudanese transition to democracy from 2019, the DUP party leader Mohamed Osman al-Mirghani returned to lead the party from Sudan in 2022, but shortly returned to Egypt.[45]

Conversely, after further imprisonment and exile, Sadiq al-Mahdi returned to Sudan in 2000 and in 2002 was elected Imam of the Ansar. In 2003 Sadiq was re-elected President of Umma, a position he kept until his death in 2020.[26] The Umma parties split to different competing factions that participated in the 2010[43][46] and 2015 general election, receiving limited support.[47]

Elections performance

| Parliamentary election | Khatmiyya | Seats | Ansar | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | National Unionist Party | -[A] | 26 | Umma Party | Umma-led parliament |

| 1953 | National Unionist Party | 51 | 22 | Umma Party | NUP goverment |

| 1958 | People's Democratic Party | 27 | 63 | Umma Party | PDP-Umma collation government |

| 1965 | People's Democratic Party | 3 | 90 | Umma Party | |

| 1968 | Democratic Unionist Party | 101 | 36 | Umma Party–Sadiq | DUP-Umma collation government |

| 30 | Umma Party–Imam | ||||

| 1986 | Democratic Unionist Party | 63 | 100 | Umma Party | |

| 2010 | Democratic Unionist Party | 4 | 8 | Umma Party and its factions | National Congress Party (NCP) government |

| 2015 | Democratic Unionist Party | 2 | 4 | Umma Party and its factions | |

- ^ NUP boycott the elections

References

- ^ Danopoulos, Constantine P. (2024-12-06). Military Disengagement from Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 1947. ISBN 978-1-040-29705-6.

- ^ Wai, Dunstan M. (2013-10-23). The Southern Sudan: The Problem of National Integration. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-135-16033-3.

- ^ Ryle, John (2011). The Sudan Handbook. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84701-030-8.

- ^ a b c d "Rivalry between the Two Sayyids al-Mirghani and al-Mahdi" (PDF). CIA. 1948-08-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g هدهود, محمود (2019-04-15). "تاريخ الحركة الإسلامية في السودان". إضاءات (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Stiansen & Kevane 1998, pp. 23–27.

- ^ Warburg 2003, pp. 89.

- ^ a b c Gaffer, Nowar (2012). "The Graduates' National Movement in Sudan, 1918-1944". SEJARAH: Journal of the Department of History. 20 (20): 125–141. doi:10.22452/sejarah.vol20no20.6. ISSN 2756-8253.

- ^ a b Hasabu, Afaf Abdel Majid Abu (1985). Factional Conflict in the Sudanese Nationalist Movement, 1918-1948. Graduate College, University of Khartoum. ISBN 978-0-86372-050-5.

- ^ Keddie 1972, pp. 377.

- ^ Keddie 1972, pp. 374.

- ^ Keddie 1972, pp. 378.

- ^ Anders, Breidlid (2014-10-20). A Concise History of South Sudan: New and Revised Edition. Fountain Publishers. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-9970-25-337-1.

- ^ a b c Holt, P. M. (1956). "Sudanese Nationalism and Self-Determination Part I". Middle East Journal. 10 (3): 239–247. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322822.

- ^ Gaffer, Nowar (2013). The Rise and Contribution of the Graduates' General Congress Towards Sudan's Independence, 1938-1956. Jabatan Sejarah, Fakulti Sastera dan Sains Sosial, Universiti Malaya.

- ^ Hasabu, Afaf Abdel Majid Abu (1985). Factional Conflict in the Sudanese Nationalist Movement, 1918-1948. Graduate College, University of Khartoum. ISBN 978-0-86372-050-5.

- ^ Warburg 2003, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Hasabu, Afaf Abdel Majid Abu (1985). Factional Conflict in the Sudanese Nationalist Movement, 1918-1948. Graduate College, University of Khartoum. ISBN 978-0-86372-050-5.

- ^ Division, Great Britain Central Office of Information Reference (1953). The Sudan, 1899-1953. British Information Services, Reference Division.

- ^ "Developments of the Quarter: Comment and Chronology". Middle East Journal. 7 (1): 58–68. 1953. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322464.

- ^ Warburg, Gabriel (1992). Historical Discord in the Nile Valley. Hurst. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-1-85065-140-6.

- ^ a b c d "About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2025-01-18.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Voll, John Obert; Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn; Lobban, Richard (1992). Historical dictionary of the Sudan. Scarecrow Press. p. 245. ISBN 9780810825475.

- ^ "Sudan Embassy in Canada". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ Warburg 2003, pp. 171.

- ^ a b c Sadig Al-Mahdi.

- ^ Elbadawi, Ibrahim (2011). Democracy in the Arab World: Explaining the Deficit. IDRC. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-415-77999-9.

- ^ a b Nohlen, Dieter; Krennerich, Michael; Thibaut, Bernhard (1999). Elections in Africa: a data handbook. New York (N.Y.) Oxford: Oxford university press. ISBN 978-0-19-829645-4.

- ^ "Fourth sovereignty Council 1967-1969".

- ^ "Heads of State". Zarate. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ Ofcansky, Thomas P. (2015). "Historical Setting". In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan: A Country Study (PDF) (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 1–58. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

- ^ Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1991). "Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69". Sudan: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: GPO for the Library of Congress – via countrystudies.us.

- ^ Fadlalla 2004, pp. 45.

- ^ Fadlalla 2004, pp. 46.

- ^ Times, Henry Tanner Special to The New York (1976-07-03). "Nimeiry Said to Thwart Coup in Sudan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-01-18.

- ^ "Sudan - National Reconciliation". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2025-01-18.

- ^ a b c Warburg, Gabriel R. (1990). "The Sharia in Sudan: Implementation and Repercussions, 1983-1989". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 624–637. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328194. Archived from the original on 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ^ "Joint Statement on Elections in Sudan" (Press release). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Norway). 20 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- ^ "Troika statement on elections in Sudan" (Press release). Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 20 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- ^ "Joint Statement on Elections in Sudan" (Press release). United States Department of State. 20 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ^ Rone, Jemera; Watch/Africa, Human Rights (1996). Behind the Red Line: Political Repression in Sudan. Human Rights Watch. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-56432-164-0.

- ^ Africa, United States Congress House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on (1991). War and Famine in the Sudan: Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Africa of the Committee on Foreign Affairs and the International Task Force of the Select Committee on Hunger, House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, Second Session, March 15, 1990. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 95.

- ^ a b Polling process of Sudan elections ends, ballot count to begin People's Daily Online

- ^ "Election results" (PDF) (in Arabic). NEC. 27 April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "Chaotic return of DUP leader to Sudan". Sudan Tribune. November 21, 2022.

- ^ Election Results of the National Assembly Archived 2011-05-29 at the Wayback Machine SSRC Making Sense of Sudan

- ^ "Election results" (PDF) (in Arabic). NEC. 27 April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

sources

- "Ansar of Sudan". BERKLEY CENTER for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- Fadlalla, Mohamed H. (2004). Short History of Sudan. iUniverse. ISBN 0-595-31425-2.

- Keddie, Nikki R. (1972). Scholars, saints, and Sufis: Muslim religious institutions in the Middle East since 1500. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02027-8.

- "Sadig Al-Mahdi". Club De Madrid. 2007-09-12. Archived from the original on 2007-10-08. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- Spiers, Edward M. (1998). Sudan: the reconquest reappraised. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4749-7.

- Stiansen, Endre; Kevane, Michael (1998). Kordofan invaded: peripheral incorporation and social transformation in Islamic Africa. BRILL. pp. 23–27. ISBN 90-04-11049-6.

- Upton, Charles (2005). Legends of the end: prophecies of the end times, Antichrist, apocalypse, and Messiah from eight religious traditions. Sophia Perennis. ISBN 1-59731-025-5.

- Warburg, Gabriel (2003). "Sayyid 'Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, 1885 - 1959". Islam, sectarianism, and politics in Sudan since the Mahdiyya. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 125–127. ISBN 0-299-18294-0.