Anglo-Australian Telescope

| |

| Part of | Australian Astronomical Observatory Siding Spring Observatory |

|---|---|

| Location(s) | New South Wales, AUS |

| Coordinates | 31°16′31″S 149°04′01″E / 31.2754°S 149.067°E |

| Organization | Australian Astronomical Observatory |

| Altitude | 1,100 m (3,600 ft) |

| Built | –1974 |

| First light | 27 April 1974 |

| Telescope style | Cassegrain reflector optical telescope |

| Diameter | 3.9 m (12 ft 10 in) |

| Collecting area | 12 m2 (130 sq ft) |

| Focal length | 12.7 m (41 ft 8 in) |

| Enclosure | spherical dome |

| Website | www |

| | |

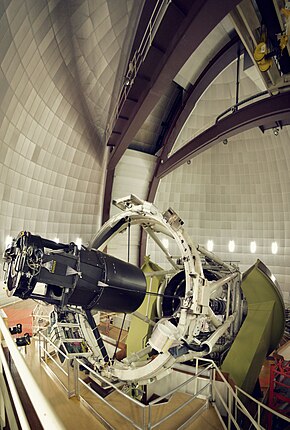

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 2009, the telescope was ranked as having the fifth-highest-impact of the world's optical telescopes. In 2001–2003, it was considered the most scientifically productive 4-metre-class optical telescope in the world based on scientific publications using data from the telescope.[1][2]

The telescope was commissioned in 1974 with a view to allowing high-quality observations of the sky from the Southern Hemisphere. At the time, most major telescopes were located in the Northern Hemisphere, leaving the southern skies poorly observed.[3] It was the largest telescope in the Southern Hemisphere from 1974 to 1976, then a close second to the Víctor M. Blanco Telescope from 1976 until 1998, when the first ESO Very Large Telescope (VLT) was opened. The AAT was credited with stimulating a resurgence in British optical astronomy.[3] It was built by the United Kingdom in partnership with Australia but has been entirely funded by Australia since 2010.[4] Observing time is available to astronomers worldwide.

The AAT was one of the last large telescopes built with an equatorial mount. More recent large telescopes have instead adopted the more compact and mechanically stable altazimuth mount. The AAT was, however, one of the first telescopes to be fully computer-controlled, and set new standards for pointing and tracking accuracy.

History

British astronomer Richard van der Riet Woolley pushed for a large optical telescope for the Southern Hemisphere in 1959.[3] In 1965, Macfarlane Burnet, president of the Australian Academy of Science, wrote to the federal education minister John Gorton inviting the federal government to support a joint British-Australian telescope project. Gorton was supportive, and nominated the Australian National University and CSIRO as Australia's representatives in the joint venture; he was unsuccessful in his attempts to induce NASA to join the project. Gorton brought the proposal before cabinet in April 1967, which endorsed the scheme and agreed to contribute half the capital and running costs. An agreement with the British was finalised a few weeks later and a Joint Policy Committee started work on construction planning in August 1967.[5] It took until September 1969 for plans to be finalised.[6] The agreement initially committed the specification to a telescope design based on the American Kitt Peak telescope until its deficiencies were known. Both the horseshoe mount and the gearing system needed improvements.[7] Although the revised gear system was considerably more expensive it was significantly more accurate, lending itself well to future applications.[7]

The mirror blank was made by Owens-Illinois in Toledo, Ohio. It was then transported to Newcastle, England, where Sir Howard Grubb, Parsons and Co took two years to grind and polish the mirror's surface.[7] Mitsubishi Electric built the mount which was constructed by August 1973. First light occurred on 27 April 1974. The telescope was officially opened by Prince Charles on 16 October 1974.[7]

Structure and telescope

The telescope is housed within a seven-story, circular, concrete building topped with a 36m diameter rotating steel dome. It was designed to withstand the high winds prevailing at that location. The slit is narrow. The dome is required to move with the telescope to avoid obstruction.[7] The top of the dome is 50m above ground level.

The telescope tube structure is supported inside a massive 12m diameter horseshoe, which rotates around the polar axis (parallel to Earth's axis) for tracking the sky. The total moving mass is 260 tonnes.[8]

The telescope has various foci for flexible instrumentation: originally there were three top-end rings which can be exchanged using the dome crane during the daytime. One was for f/3.3 prime-focus, with corrector lenses and a cage for a human observer taking photographs (rarely used after the 1980s); one has a large secondary mirror giving an f/8 Cassegrain focus; and a third top-end has smaller f/15 and f/36 secondary mirrors. A fourth top-end was built in the 1990s to give a 2-degree field of view at prime focus, with 400 optical fibres feeding the 2dF instrument and its later enhancements AAOmega and HERMES.

Instruments

The AAT is equipped with a number of instruments, including:

- The Two Degree Field facility (2dF), a robotic optical fibre positioner for obtaining spectroscopy of up to 400 objects over a 2° field of view simultaneously.

- The University College London Échelle Spectrograph (UCLES), a high-resolution optical spectrograph which has been used to discover many extrasolar planets.

- IRIS2, a wide-field infrared camera and spectrograph.

The newest instrument, HERMES, was commissioned in 2015. It is a new high-resolution spectrograph to be used with the 2dF fibre positioner.[9] HERMES is mainly being used for the 'Galactic Archaeology with Hermes' (GALAH) Survey, which aims to reconstruct the history of our galaxy's formation from precise multi-element (~25 elements) abundances of 1 million stars derived from HERMES spectra.

Comparisons

| # | Name / Observatory |

Image | Aperture | M1 Area |

Altitude | First Light |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | BTA-6 (Special Astrophysical Obs) |

|

238 inch 605 cm |

26 m2 | 2,070 m (6,790 ft) | 1975 |

| 2. | Hale Telescope (Palomar Observatory) |

|

200 inch 508 cm |

20 m2 | 1,713 m (5,620 ft) | 1949 |

| 3. | Mayall Telescope (Kitt Peak National Obs.) |

|

158 inch 401 cm |

10 m2 | 2,120 m (6,960 ft) | 1973 |

| 4. | Víctor M. Blanco Telescope (CTIO Observatory) |

|

158 inch 401 cm |

10 m2 | 2,200 m (7,200 ft) | 1976 |

| 5. | Anglo-Australian Telescope (Siding Spring Observatory) |

|

153 inch 389 cm |

12 m2 | 1,742 m (5,715 ft) | 1974 |

| 6. | ESO 3.6 m Telescope (La Silla Observatory) |

|

140 inch 357 cm |

8.8 m2 | 2,400 m (7,900 ft) | 1976 |

| 7. | Shane Telescope (Lick Observatory) |

|

120 inch 305 cm |

~7 m2 | 1,283 m (4,209 ft) | 1959 |

See also

- List of largest optical reflecting telescopes

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 20th century

References

- ^ Watson, Fred (6 January 2009). "Across the universe". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Plonter, Tammy (11 September 2008). "Australian Telescope Leads the World in Astronomy Research". Universe Today.

- ^ a b c Home, Roderick Weir (1990). Australian Science in the Making. Cambridge University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0521396409. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Lomb, Nick (15 June 2010). "Australia's largest optical telescope to become part of the Australian Astronomical Observatory on 1 July 2010 and to celebrate its 36th birthday". Sydney Observatory.

- ^ Hancock, Ian (2002). John Gorton: He Did It His Way. Hodder. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Gregory, Jane (2005). Fred Hoyle's Universe. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 0191578460. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, Raymond (1996). Explorers of the Southern Sky: A History of Australian Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 382–394. ISBN 0521365759. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "The Anglo-Australian Telescope". Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "HERMES project AAT". Department of Industry, Innovation, Climate Change, Science, Research and Tertiary Education. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.