Bithynia

| Bithynia (Βιθυνία) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

Bithynia and Pontus as a province of the Roman Empire, 125 AD | |

| Location | Northern Anatolia, present-day Turkey |

| State existed | 297–74 BC |

| Nation | Greeks, Bithyni, Thyni |

| Historical capitals | Nicomedia (İzmit), Nicaea (İznik) |

| Roman province | Bithynia |

| |

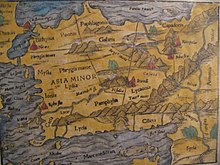

Bithynia (/bɪˈθɪniə/; Koinē Greek: Βιθυνία, romanized: Bithynía) was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Paphlagonia to the northeast along the Pontic coast, and Phrygia to the southeast towards the interior of Asia Minor.

Hellenistic Bithynia was an independent kingdom from the 4th century BC. Its capital Nicomedia was rebuilt on the site of ancient Astacus in 264 BC by Nicomedes I of Bithynia. Bithynia was bequeathed to the Roman Republic in 74 BC, and became united with the Pontus region as the province of Bithynia and Pontus. In the 7th century it was incorporated into the Byzantine Opsikion theme. It became a border region to the Seljuk Empire in the 13th century, and was eventually conquered by the Ottoman Turks between 1325 and 1333.

Description

Several major cities sat on the fertile shores of the Propontis (which is now known as Sea of Marmara): Nicomedia, Chalcedon, Cius and Apamea. Bithynia also contained Nicaea, noted for being the birthplace of the Nicene Creed.

According to Strabo, Bithynia was bounded on the east by the river Sangarius (modern Sakarya river), but the more commonly received division extended it to the Parthenius, which separated it from Paphlagonia, thus comprising the district inhabited by the Mariandyni. On the west and southwest it was separated from Mysia by the river Rhyndacus and on the south it adjoined Phrygia and Galatia.[1]

It is occupied by mountains and forests, but has valleys and coastal districts of great fertility. The most important mountain range is the (so-called) "Mysian" Olympus (8,000 ft, 2,400 m), which towers above Bursa and is clearly visible as far away as Istanbul (70 miles, 110 km). Its summits are covered with snow for a great part of the year.[1]

East of this the range extends for more than 100 miles (160 km), from the Sakarya to Paphlagonia. Both of these ranges are part of the border of mountains which bound the great tableland of Anatolia, Turkey. The broad tract which projects towards the west as far as the shores of the Bosporus, though hilly and covered with forests—the Turkish Ağaç Denizi, or "The sea of Trees"—is not traversed by any mountain chain. The west coast is indented by two deep inlets, the northernmost, the Gulf of İzmit (ancient Gulf of Astacus), penetrating between 40 and 50 miles (64 and 80 km) into the interior as far as İzmit (ancient Nicomedia), separated by an isthmus of only about 25 miles (40 km) from the Black Sea; and the Gulf of Mudanya or Gemlik (Gulf of Cius), about 25 miles (40 km) long. At its extremity is situated the small town of Gemlik (ancient Cius) at the mouth of a valley, communicating with the lake of Iznik, on which was situated Nicaea.[1]

The principal rivers are the Sangarios which traverses the province from south to north; the Rhyndacus, which separated it from Mysia; and the Billaeus (Filyos), which rises in the Aladağ, about 50 miles (80 km) from the sea, and after flowing by modern Bolu (ancient Bithynion-Claudiopolis) falls into the Euxine, close to the ruins of the ancient Tium, about 40 miles (64 km) northeast of Heraclea Pontica (the modern Karadeniz Ereğli), having a course of more than 100 miles (160 km). The Parthenius (modern Bartın), the eastern boundary of the province, is a much less considerable stream.[1]

The valleys towards the Black Sea abound in fruit trees of all kinds, such as oranges, while the valley of the Sangarius and the plains near Bursa and Iznik (Nicaea) are fertile and well cultivated. Extensive plantations of mulberry trees supply the silk for which Bursa has long been celebrated, and which is manufactured there on a large scale.[1]

History

Iron Age

Bithynia is named for the Thracian tribe of the Bithyni, mentioned by Herodotus (VII.75) alongside the Thyni. The "Thraco-Phrygian" migration from the Balkans to Asia Minor would have taken place at some point following the Bronze Age collapse or during the early Iron Age. The Thyni and Bithyni appear to have settled simultaneously in the adjoining parts of Asia, where they expelled or subdued the Mysians, Caucones and other minor tribes, the Mariandyni maintaining themselves in the northeast. Herodotus mentions the Thyni and Bithyni as settling side by side.[1] No trace of their original language has been preserved, but Herodotus describes them as related to the tribes of Thracian extraction.

Later the Greeks established on the coast the colonies of Cius (modern Gemlik); Chalcedon (modern Kadıköy), at the entrance of the Bosporus, nearly opposite Byzantium (modern Istanbul) and Heraclea Pontica (modern Karadeniz Ereğli), on the Euxine, about 120 miles (190 km) east of the Bosporus.[2]

The Bithynians were incorporated by king Croesus within the Lydian monarchy, with which they fell under the dominion of Persia (546 BC), and were included in the satrapy of Phrygia, which comprised all the countries up to the Hellespont and Bosporus.[1]

Kingdom of Bithynia

Even before the conquest by Alexander the Bithynians appear to have asserted their independence, and successfully maintained it under two native princes, Bas and Zipoites, the latter of whom assumed the title of king (basileus) in 297 BC.

His son and successor, Nicomedes I, founded Nicomedia, which soon rose to great prosperity, and during his long reign (c. 278 – c. 255 BC), as well as those of his successors, Prusias I, Prusias II and Nicomedes II (149–91 BC), the kings of Bithynia had a considerable standing and influence among the minor monarchies of Anatolia. But the last king, Nicomedes IV, was unable to maintain himself in power against Mithridates VI of Pontus. After being restored to his throne by the Roman Senate, he bequeathed his kingdom through his will to the Roman Republic (74 BC).[2]

The coinage of these kings show their regal portraits, which tend to be engraved in an extremely accomplished Hellenistic style.[3]

Roman province

As a Roman province, the boundaries of Bithynia changed frequently. During this period, Bithynia was commonly united for administrative purposes with the province of Pontus within the Roman Empire. This was the situation at the time of Emperor Trajan, when Pliny the Younger was appointed governor of the combined provinces (109/110 – 111/112), a circumstance which has provided historians with valuable information concerning the Roman provincial administration at that time.

Byzantine province

Under the Byzantine Empire, Bithynia was again divided into two provinces, separated by the Sangarius. Only the area to the west of the river retained the name of Bithynia.[2]

Bithynia attracted much attention because of its roads and its strategic position between the frontiers of the Danube in the north and the Euphrates in the south-east. To secure communications with the eastern provinces, the monumental bridge across the river Sangarius was constructed around 562 AD. Troops frequently wintered at Nicomedia.

During this time, the most important cities in Bithynia were Nicomedia, founded by Nicomedes, and Nicaea. The two had a long rivalry with each other over which city held the rank of capital.

Notable people

- Hipparchus of Nicaea (2nd century BC), Greek astronomer, discovered precession and discovered how to predict the timing of eclipses

- Theodosius of Bithynia (2nd century BC), Greek astronomer and mathematician

- Asclepiades of Bithynia (c. 169 BC – c. 100 BC), Greek physician

- Antinous (2nd century), Catamite and eromenos of the Roman Emperor Hadrian

- Cassius Dio (c. 155 – c. 235), Roman historian, senator, and consul

- Arrian (Lucius Flavius Arrianus), Greek historian, c. 86–160

- Helena, mother of Constantine the Great c. 250 – c. 330

- Phrynichus Arabius (2nd century), grammarian

- Auxentius of Bithynia (c. 400 – 473), hermit

- Hypatius of Bithynia (died c. 450), hermit

- Vendemianus of Bithynia (6th century), hermit

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm 1911, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 13.

- ^ "Kings of Bithynia - Asia Minor Coins - Photo Gallery". www.asiaminorcoins.com.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bithynia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13.

Further reading

- Hellenistic

- Paganoni, Eloisa (2019). Forging the Crown: A History of the Kingdom of Bithynia from Its Origin to Prusias I. "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-913-1895-4.

- Michels, Christoph (2008). Kulturtransfer und Monarchischer Philhellenismus: Bithynien, Pontos und Kappadokien in Hellenistischer Zeit (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH KG. ISBN 978-3-89971-536-1.

- Scholten, Joseph (2019). "Building Hellenistic Bithynia". In Elton, Hugh; Reger, Gary (eds.). Regionalism in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor. Ausonius Éditions. pp. 17–24. ISBN 978-2-35613-276-5.

- Roman

- Bekker-Nielsen, Tonnes (2008). Urban Life and Local Politics in Roman Bithynia: The Small World of Dion Chrysostomos. Aarhus Universitetsforlag. ISBN 978-87-7124-752-7. Archived from the original on 2012-03-01.

- Bowie, Ewen (2022). "Greek High Culture in Hellenistic and Early Imperial Bithynia: Towards a Prosopography of Practitioners of Greek Culture in Bithynia Down to the Middle of the Third Century AD". Mnemosyne. 75 (1): 73–112. doi:10.1163/1568525X-bja10120. ISSN 0026-7074.

- Harris, B. F. (2016). Temporini, Hildegard (ed.). "Bithynia: Roman Sovereignty and the Survival of Hellenism". Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. 2.7.2: 857–901. doi:10.1515/9783110860429-007. ISBN 9783110860429.

- Marek, Christian (2003). Pontus et Bithynia: die römischen Provinzen im Norden Kleinasiens (in German). Von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2925-5.

- Storey, Stanley Jonathon (1999) [1998]. Bithynia: history and administration to the time of Pliny the Younger (PDF). Ottawa: National Library of Canada. ISBN 0-612-34324-3. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- Byzantine

- Darrouzès, Jean, ed. (1981). Notitiae Episcopatuum Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae. Paris: Institut français d'études byzantines.

- Komatina, Predrag (2014). "Settlement of the Slavs in Asia Minor During the Rule of Justinian II and the Bishopric των Γορδοσερβων" (PDF). Београдски историјски гласник: Belgrade Historical Review. 5: 33–42.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.