Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant

Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant August 28, 1880 Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil |

| Died | June 20, 1970 (aged 89) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Pen name | Helena Morley |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | Brazilian |

| Period | 1893-1895 |

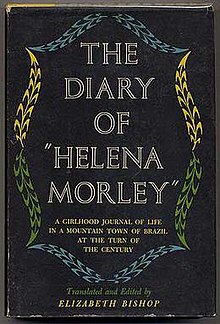

Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant (August 28, 1880 – June 20, 1970) was a Brazilian juvenile writer. When she was a teenager, she kept a diary, which describes life in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil[1][2] which was then published in 1942. The diary was published under a pen name Helena Morley.[2][1] When it was originally published it was in portuguese under the title Minha Vida de Menina.[2] The diary was then translated in to English by Elizabeth Bishop in 1957.[1]

Biography

She was born in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil to an English father and a Brazilian mother.[3] Her father worked as a diamond miner.[4] The diary chronicles Brant's daily life, and covers her teenage years until 1895.[5]

In 1900 Brant married Augusto Mário Calderia Brant, they had five children together.[3] Brant says that she published her diaries in order to act as a role model for younger females who may read the book.[6] She wrote that the diary was a way to show young women what becoming an adult means, and in this way she is acting like a grandmother to the reader.[6] One of her daughters, Ignez Caldeira Brant, married with Abgar Renault, Brazilian Ministry of Education (1955-1956) and of the federal accountability office, Tribunal de Contas da União (1967-1973).[7]

Published work

Brant's only published work is The Diary of Helena Morley, which she began writing when she attended the Normal School.[4] The diary discusses her daily life in the diamond mining town of Diamantina, romantic interests, but it also deals with heavier topics like loss.[8] The book also discusses relationships, marriage in particular, but also social affairs and Brant's dreams.[9] The topics of the book make it so that it could be a diary of a present day teenager rather than one 60 years ago.[5] Since Brant discusses her everyday life, insights about that point in history are able to be gained by reading the diary, particularly about the effects of the abolition of slavery.[10] There is very little documentation about life post emancipation, making the diary an important resource for historians.[11] Brant is praised for her ability to add humor to the discussion of racism, which typically is associated with seriousness.[12] Another reason Brant's book was so popular is the nostalgic that it brings the reader, the provincial life of a small town, that the reader is able to find peace in the description of the simple life.[6]

Reception

The book attracted attention like many other diaries of young women.[10] The prevalence of young female diaries is explained for many of the same reasons Brant's own diary is popular.[6][10] That they allow the reader to feel young again and reminisce about when they were a teenager.[10][6] Some of the first attention that was drawn to Brant for her work was after Alexandre Eulálio praised Brant for her work these praises placed Brant among classic Brazilian authors.[6] French author Georges Bernanos also made the public aware of the book.[11] Elizabeth Bishop was originally drawn to the work in 1952, then in 1957 Bishop published her English translation of the book.[4] Bishop says that she was drawn to Brant's work because of Brant's impressive skills of observation and ability to recreate a scene using only words.[4] Some have compared Brant's work to Jane Austen that even though she was from a small town in Brazil, its style is like work from England.[9]

References

- ^ a b c Morley, Helena (1995). The diary of "Helena Morley". Bishop, Elizabeth, 1911-1979. New York: Noonday Press/Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374524357. OCLC 32015656.

- ^ a b c Morley, Helena (1998). Minha vida de menina. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-8571647688. OCLC 40615889.

- ^ a b "Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant". 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ^ a b c d Wood, Susan (1978-04-09). "The Diary of "Helena Morley" Translated and edited by Elizabeth Bishop". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ a b Miranda, France (2014-08-09). "The Diary of Helena Morley". The Spectator. Translated by Bishop, Elizabeth.

- ^ a b c d e f Karpa-Wilson, Sabrina (2000-04-01). "The Dangerous Business of Diary Writing in Helena Morley's "Minha Vida Menina"". Romance Notes. 40: 303–312.

- ^ "Augusto Mario Caldeira Brant". Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ^ McCabe, Susan (1994). Elizabeth Bishop : her poetics of loss. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271010472. OCLC 28721921.

- ^ a b Moser, Gerald M. (1979). "Reviewed Work: The Diary of "Helena Morley." by Helena Morley [Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant], Elizabeth Bishop". World Literature Today. 53 (1): 93–94. JSTOR 40132494.

- ^ a b c d Begos, Jane DuPree (1987). "The diaries of adolescent girls". Women's Studies International Forum. 10 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(87)90096-3.

- ^ a b Brown, Ashley (1977-10-01). "Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil". The Southern Review. 13: 688 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Books: Rich Little Poor Girl". Time. 1957-12-30. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

External links

- 1957 Time article on Brant and her book

- Letters, photos, and texts about Helena Morley - Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant - Agosto de 2003 collected by the writer and educator Vera Brant.