Lajjun

Lajjun اللجّون Legio, al-Lajjun, el-Lejjun | |

|---|---|

Lajjun, 1924. Roman or Byzantine columns and modern huts (Rockefeller Museum). | |

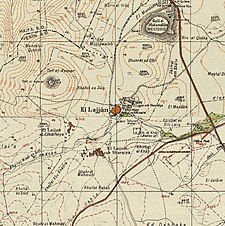

A series of historical maps of the area around Lajjun (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°34′29″N 35°10′40″E / 32.57472°N 35.17778°E | |

| Palestine grid | 167/220 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jenin |

| Date of depopulation | May 30, 1948[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 77,242 dunams (77.242 km2 or 29.823 sq mi) |

| Population (1948) | |

• Total | 1,280 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Kibbutz Megiddo[2] |

Lajjun (Arabic: اللجّون, al-Lajjūn) was a large Palestinian Arab village located 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) northwest of Jenin and 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) south of the remains of the biblical city of Megiddo. The Israeli kibbutz of Megiddo, Israel was built 600 metres north-east of the depopulated village on the hill called Dhahrat ed Dar from 1949.

Named after an early Roman legion camp in Syria Palaestina province called "Legio", predating the village at that location, Lajjun's history of habitation spanned some 2,000 years. Under Abbasid rule it was the capital of a subdistrict, during Mamluk rule it served as an important station in the postal route, and during Ottoman rule it was the capital of a district that bore its name. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire towards the end of World War I, Lajjun and all of Palestine was placed under the administration of the British Mandate. The village was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, when it was captured by Israel. Most of its residents subsequently fled and settled in the nearby town of Umm al-Fahm.

Etymology

The name Lajjun derives from the Roman name Legio, referring to the Roman legion stationed there. In the 3rd century, the town was renamed Maximianopolis ("City of Maximian") by Diocletian in honor of Maximian, his co-emperor,[3] but the inhabitants continued to use the old name. Under the Caliphate, the name was Arabicized into al-Lajjûn or el-Lejjûn,[4] which was used until the Crusaders conquered Palestine in 1099. The Crusaders restored the Roman name Legio, and introduced new names such as Ligum and le Lyon, but after the town was reconquered by the Muslims in 1187,[5] al-Lajjun once again became its name.

Geography

Modern Lajjun was built on the slopes of three hills, roughly 135–175 meters above sea level,[6] located on the southwestern edge of the Jezreel Valley (Marj ibn Amer). Jenin, the entire valley, and Nazareth range are visible from it. The village was located on both the banks of a stream, a tributary of Kishon River. The stream flows to the north and then east over 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) before arriving at Lajjun. That section is called Wadi es-Sitt (valley of the lady) in Arabic,[7] The northern quarter was built in close proximity to a number of springs, including 'Ayn al Khalil, 'Ayn Nasir, 'Ayn Sitt Leila, and 'Ayn Jumma, collectively known as 'Uyun Seil Lajjun.[8] The eastern quarter was next to 'Ayn al Hajja.[9] From Lajjun onward the stream is called Wadi al-Lajjun in Arabic.[10][11] In Hebrew, the Israeli Government Naming Committee decided in 1958 to use the name Nahal Qeni (Hebrew: נַחַל קֵינִי) for the entire length of the stream, based on its ancient identification (see below).[12] Lajjun is bordered by Tall al-Mutsallem to the northeast, and by Tall al-Asmar to the northwest. Lajjun, which was linked by secondary roads to the Jenin-Haifa road, and the road that led southwest to the town of Umm al-Fahm, laid close to the junctions of the two highways.[13]

Nearby localities included, the destroyed village of Ayn al-Mansi to the northwest, and the surviving villages of Zalafa to the south, Bayada and Musheirifa to the southwest, and Zububa (part of the Palestinian territories) to the southeast. The largest town near al-Lajjun was Umm al-Fahm, to the south.[14]

History

Bronze and Iron Ages

Lajjun is about 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) south of Tel Megiddo, also called Tell al-Mutasallim, which is identified with ancient Megiddo.[5] During the rule of the Canaanites and then the Israelites, Megiddo, located on the military road leading from Asia to Egypt and in a commanding situation, was heavily fortified by both peoples.

Lajjun stream has been identified with the brook Kina, or Qina, which is mentioned in the Egyptian descriptions of Thutmose III's Battle of Megiddo. According to the reconstruction of Harold Hayden Nelson, the entire battle was fought in the valley, between the three quarters of modern Lajjun.[15] However, both Na'aman[16] and Zertal[17][18] suggested alternative locations for Qina. This stream may be the "Waters of Megiddo" in the Song of Deborah[19] In the same context, Judges 4 attests to the presence of a branch of the Kenite clan somewhere in the area; relating this name to Thutmose's Annals, scholars like Shmuel Yeivin theorized that the name Qina derives from qyni (Hebrew: קיני).[20] Donald B. Redford noted that the Egyptian transliteration might be of "qayin".[21]

Roman era

Modern-day historical geographers have placed the Second Temple period village of Kefar ʿUthnai (Hebrew: כפר עותנאי) in the confines of the Arab village, and which place-name underwent a change after a Roman Legion had camped there.[22][23] It appears in Latin characters under its old name Caporcotani in the Tabula Peutingeriana Map, and lay along the Roman road from Caesarea to Scythopolis (Beit Shean).[24][25][26] Ptolemy (Geography V, 15: 3) also mentions the site in the second century CE, referring to the place under its Latin appellation, Caporcotani, and where he mentions it as one of the four cities of the Galilee, with Sepphoris, Julias and Tiberias.[27] Among the village's famous personalities was Rabban Gamliel.[28] After the Bar Kochba Revolt—a Jewish uprising against the Roman Empire—had been suppressed in 135 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian ordered a second Roman legion, Legio VI Ferrata (6th "Ironclad" Legion), to be stationed in the north of the country to guard the Wadi Ara region, a crucial line of communication between the coastal plain of Palestine and the Jezreel Valley.[5][29] The place where it established its camp was known as Legio.

In the 3rd century CE, when the army was removed, Legio became a city and its name was augmented with the adjectival Maximianopolis.[3][29] Eusebius mentions the village in his Onomasticon, under the name Legio.

In 2001 and 2004, the Israel Antiquities Authority conducted archaeological excavations at Kefar ‘Otnay and Legio west of Megiddo Junction, recovering artifacts from the Roman and early Byzantine periods.[30][31]

Early Muslim period

Some Muslim historians believe the site of the Battle of Ajnadayn between the Muslim Arabs and the Byzantines in 634 CE was at Lajjun. Following the Muslim victory, Lajjun, along with most of Palestine, and southern Syria were incorporated into the Caliphate.[32] According to medieval geographers Estakhri and Ibn Hawqal, Lajjun was the northernmost town of Jund Filastin (military district of Palestine).[33]

A hoard of dinars dating from the Umayyad era have been found at Lajjun.[34]

The 10th-century Persian geographer Ibn al-Faqih wrote of a local legend related by the people of Lajjun regarding the source of the abundant spring used as the town's primary water source over the ages:

there is just outside al-Lajjun a large stone of round form, over which is built a dome, which they call the Mosque of Abraham. A copious stream of water flows from under the stone and it is reported that Abraham struck the stone with his staff, and there immediately flowed from it water enough to suffice for the supply of the people of the town, and also to water their lands. The spring continues to flow down to the present day.[35]

In 940, Ibn Ra'iq, during his conflict over control of Syria with the Ikhshidids of Egypt, fought against them in an indecisive battle at Lajjun. During the battle, Abu Nasr al-Husayn—the Ikhshidid general and brother of the Ikhshidid ruler, Muhammad ibn Tughj—was killed. Ibn Ra'iq was remorseful at the sight of Husayn's dead body and offered his seventeen-year-old son, Abu'l-Fath Muzahim, to Ibn Tughj "to do with him whatever they saw fit". Ibn Tughj was honored by Ibn Ra'iq's gesture; instead of executing Muzahim, he gave the latter several gifts and robes, then married him to his daughter Fatima.[36]

In 945, the Hamdanids of Aleppo and the Ikhshidids fought a battle in Lajjun. It resulted in an Ikhshidid victory putting a halt to Hamdanid expansion southward under the leadership of Sayf al-Dawla.[13] The Jerusalemite geographer, al-Muqaddasi, wrote in 985 that Lajjun was "a city on the frontier of Palestine, and in the mountain country ... it is well situated and is a pleasant place".[37] Moreover, it was the center of a nahiya (subdistrict) of Jund al-Urdunn ( (military district of Jordan),[38] which also included the towns of Nazareth and Jenin.[39][40]

Crusader, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

When the Crusaders invaded and conquered the Levant from the Fatimids in 1099, al-Lajjun's Roman name, Legio, was restored and the town formed a part of the lordship of Caesarea. During this time, Christian settlement in Legio grew significantly. John of Ibelin records that the community "owed the service of 100 sergeants". Bernard, the archbishop of Nazareth granted some of the tithes of Legio to the hospital of the monastery of St. Mary in 1115, then in 1121, he extended the grant to include all of Legio, including its church as well as the nearby village of Ti'inik. By 1147, the de Lyon family controlled Legio, but by 1168, the town was held by Payen, the lord of Haifa. Legio had markets, a town oven and held other economic activities during this era. In 1182, the Ayyubids raided Legio, and in 1187, it was captured by them under the leadership of Saladin's nephew Husam ad-Din 'Amr and consequently its Arabic name, Lajjun, was restored.[5]

In 1226, Arab geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi writes of the Mosque of Abraham in Lajjun, the town's "copious stream", and that it was a "part of the Jordan Province".[41] A number of Muslim kings and prominent persons passed through the village, including Ayyubid sultan al-Kamil, who gave his daughter 'Ashura' in marriage to his nephew while visiting the town in 1231.[42] The Ayyubids ceded Lajjun to the Crusaders in 1241, but it fell to the Mamluks under Baibars in 1263. A year later, a party of Templars and Hospitallers raided Lajjun and took 300 men and women captives to Acre. In the treaty between Sultan Qalawun and the Crusaders on 4 June 1283, Lajjun was listed as the Mamluk territory.[5]

By 1300, the Levant was entirely in Mamluk hands and divided into several provinces. Lajjun became the center of an ʿAmal (subdistrict) in the Mamlaka of Safad (ultimately becoming one of sixteen[43]). In the 14th century members of a Yamani tribe lived there.[44] Shams al-Din al-'Uthmani, writing probably in the 1370s, reported it was the seat of Marj ibn Amer, and had a great khan for travellers, a "terrace of the sultan" and the Maqam (shrine) of Abraham.[45] The Mamluks fortified it in the 15th century and the town became a major staging post on the postal route (braid) between Egypt and Damascus.[5]

Ottoman era

Early rule and the Tarabay family

The Ottoman Empire conquered most of Palestine from the Mamluks after the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1517.

As the army of Sultan Selim I moved south towards Egypt,[46] Tarabay ibn Qaraja, chieftain of the Bani Hareth, a Bedouin tribe from the Hejaz, supported them by contributing guides and scouts.[47] When the Mamluks were completely uprooted and Selim returned to Istanbul, the Tarabays were granted the territory of Lajjun. The town eventually became the capital of the Sanjak ("District") of Lajjun, which was a part of the province of Damascus, and encompassed the Jezreel Valley, northern Samaria, and a part of the north-central coastline of Palestine as its territory.[48][49][50] It was composed of four nahiyas ("sub-districts") (Jinin, Sahel Atlit, Sa'ra, and Shafa), and encompassed a total of 55 villages, including Haifa, Jenin, and Baysan.[51]

After a short period in which the Tarabays were in a state of rebellion, tensions suddenly died down and the Ottomans appointed Ali ibn Tarabay as the governor of Lajjun in 1559. His son Assaf Tarabay ruled Lajjun from 1571 to 1583. During his reign, he extended Tarabay power and influence to Sanjak Nablus.[46] In 1579, Assaf, referred to as the "Sanjaqbey of al-Lajjun," is mentioned as the builder of a mosque in the village of al-Tira.[52] Assaf was deposed and banished in 1583 to the island of Rhodes. Six years later, in 1589, he was pardoned and resettled in the town. At the time, an impostor also named Assaf, had attempted to seize control of Sanjak Lajjun. Known later as Assaf al-Kadhab ("Assaf the Liar"), he was arrested and executed in Damascus where he traveled in attempt to confirm his appointment as governor of the district.[46] In 1596, Lajjun was a part of the nahiya of Sha'ra and paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, as well as goats, beehives and water buffaloes.[53]

Assaf Tarabay was not reinstated as governor, but Lajjun remained in Tarabay hands, under the rule of Governor Tarabay ibn Ali who was succeeded upon his death by his son Ahmad in 1601, who also ruled until his death in 1657. Ahmad, known for his courage and hospitality,[46] helped the Ottomans defeat the rebel Ali Janbulad and gave shelter to Yusuf Sayfa—Janbulad's principal rival. Ahmad, in coordination with the governors of Gaza (the Ridwan family) and Jerusalem (the Farrukh family), also fought against Fakhr ad-Din II in a prolonged series of battles,[46] which ended with the victory of the Tarabay-Ridwan-Farrukh alliance after their forces routed Fakhr ad-Din's army at the al-Auja river in central Palestine in 1623.[54]

The Ottoman authorities of Damascus expanded Ahmad's fief as a token of gratitude. Ahmad's son Zayn Tarabay ruled Lajjun for a brief period until his death in 1660. He was succeeded by Ahmad's brother Muhammad Tarabay, who—according to his French secretary—had good intentions for governing Lajjun, but was addicted to opium and as a result had been a weak leader. After his death in 1671, other members of the Tarabay family ruled Lajjun until 1677 when the Ottomans replaced them with a government officer.[47] The main reason behind the Ottoman abandonment of the Tarabays was that their larger tribe, the Bani Hareth, migrated east of Lajjun to the eastern banks of the Jordan River.[55] Later during this century, Sheikh Ziben, ancestor to the Arrabah-based Abd al-Hadi clan, became the leader of Sanjak Lajjun.[51] When Henry Maundrell visited in 1697, he described the place as "an old village near which was a good khan".[56]

Later Ottoman rule

Much of the Lajjun district territories were actually taxed by the stronger families of Sanjak Nablus by 1723. Later in the 18th century, Lajjun was replaced by Jenin as the administrative capital of the sanjak which now included the Sanjak of Ajlun. By the 19th century it was renamed Sanjak Jenin, although 'Ajlun was separated from it.[58] Zahir al-Umar, who became the effective ruler of the Galilee for a short period during the second half of the 18th century, was reported to have used cannons against Lajjun in the course of his campaign between 1771–1773 to capture Nablus.[59] It is possible that this attack led to the village's decline in the years that followed.[60] By that time, Lajjun's influence was diminished by the increasing strength of Acre's political power and Nablus's economic muscle.[58]

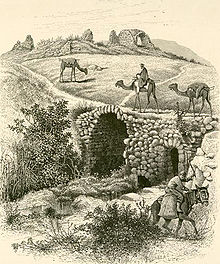

Edward Robinson visited in 1838, and noted that the khan, which Maundrell commented on, was for the accommodation of the caravans passing on the great road between Egypt and Damascus which comes from the western plain along the coast, over the hills to Lajjun, and enters the plain of Esdraelon.[62] When the British consul James Finn visited the area in the mid-19th century, he did not see a village.[63] The authors of the Survey of Western Palestine also noticed a khan, south of the ruins of Lajjun in the early 1880s.[64] Gottlieb Schumacher saw caravans resting at the Lajjun stream in the early 1900s.[65]

Andrew Petersen, inspecting the place in 1993, noted that the principal extant buildings at the site are the khan and a bridge. The bridge, which crosses a major tributary of the Kishon River, is approximately 4 meters (13 ft) wide and 16 meters (52 ft) to 20 meters (66 ft) long. It is carried on three arches, the north side has been robbed of its outer face, while the south side is heavily overgrown with vegetation. According to Petersen, the bridge was already in ruins when drawn by Charles William Wilson in the 1870s. The khan is located on a low hill 150 meters (490 ft) to the southwest of the bridge. It is a square enclosure measuring approximately 30 meters (98 ft) per side with a central courtyard. The ruins are covered with vegetation, and only the remains of one room is visible.[66]

The modern village of Lajjun was a satellite village Umm al-Fahm. During its existence it came to eclipse its mother settlement in infrastructure and economic importance.[67] Originally, in the late 19th century, Arabs from Umm al-Fahm started to make use of the Lajjun farmland, settling for the season.[13][42][68] Gradually, they settled in the village, building their houses around the springs. In 1903–1905, Schumacher excavated Tell al-Mutasallim (ancient Megiddo) and some spots in Lajjun. Schumacher wrote that Lajjun ("el-Leddschōn") is properly the name of the stream and surrounding farmlands,[69] and calls the village along the stream Ain es-Sitt. Which, he noted, "consists of only nine shabby huts in the midst of ruins and heaps of dung." and a few more fellahin huts south of the stream.[70] By 1925 some of the inhabitants of Lajjun reused stones from the ancient structure that had been unearthed to build new housing.[71] At some point in the early 20th century the four hamulas ("clans") of Umm al-Fahm divided the land among themselves: al-Mahajina, al-Ghubariyya, al-Jabbarin and al-Mahamid clans.[72][73] Lajjun thus transformed into three ‘Lajjuns’, or administratively separate neighbourhoods reflecting the Hebronite/Khalīlī settlement pattern of its founders.[74]

Taken more broadly, Lajjun was one of the settlements of the so-called "Fahmawi Commonwealth", a network of interspersed communities connected by ties of kinship, and socially, economically and politically affiliated with Umm al Fahm. The Commonwealth dominated vast sections of Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, Wadi 'Ara and Marj Ibn 'Amir/Jezreel Valley during that time.[74]

British Mandate period

More people moved to Lajjun during the British mandate period, particularly in the late thirties, due to the British crackdown on participants in the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine.[60] The tomb of Yusuf Hamdan, a local leader of the revolt, is located in the village.[75] Others moved in as they came to understand that the Mandate authorities planned to turn Lajjun into a county seat.[76] During 1940–1941, a police station belonging to the Tegart forts system was constructed at the road intersection outside Lajjun by the British Mandate government.[77]

Lajjun's economy grew rapidly as a result of the influx of the additional population.[60] As the village expanded, it was divided into three quarters, one to the east, one to the west, and the older one in the north. Each quarter was inhabited by one or more hamula ("clan").[68]

Lajjun had a school that was founded in 1937 and that had an enrollment of 83 in 1944. It was located in the quarter belonging to the al-Mahajina al-Fawqa clan, that is, in Khirbat al-Khan. In 1943, one of the large landowners in the village financed the construction of a mosque, built of white stone, in the al-Ghubariyya (eastern) quarter. Another mosque was also established in the al-Mahamid quarter during the same period, and was financed by the residents themselves.[68] It was a four-year elementary school for boys.[78]

In 1945, Lajjun, Umm al-Fahm and seven hamlets had a total land area of 77.24 square kilometres (29.82 sq mi), of which 68.3 square kilometres (26.4 sq mi) was Arab-owned, and the remainder being public property.[79][80] There was a total of 50 km2 (12,000 acres) of land that was cultivated; 4.3 km2 (1,100 acres) were used for plantations and irrigated, and 44.6 km2 (11,000 acres) were planted with cereals (wheat and barley).[81] The built-up area of the villages was 0.128 km2 (32 acres), most of it being in Umm al-Fahm and Lajjun.[82] Former villagers recall they grew wheat and corn in the fields, and irrigated crops such as eggplant, tomato, okra, cowpea and watermelon.[83] A survey map from 1946 shows most of the buildings in the eastern and western quarters as built from stone and mud,[9] but some used mud over wood.[84] Many houses had neighbouring small plots marked as "orchards".[9]

There was a small market place in the village, as well as six grain mills (powered by the numerous springs and wadis in the vicinity), and a health center.[68] The various quarters of Lajjun had many shops. A bus company was established in Lajjun by a villager from Umm al-Fahm; the bus line served Umm al-Fahm, Haifa, and a number of villages, such as Zir'in. In 1937, the line had seven buses. Subsequently, the company was licensed to serve Jenin also, and acquired the name of "al-Lajjun Bus Company".[85]

In addition to agriculture, residents practiced animal husbandry which formed was an important source of income for the town. In 1943, they owned 512 heads of cattle, 834 sheep over a year old, 167 goats over a year old, 26 camels, 85 horses, 13 mules, 481 donkeys, 3822 fowls, 700 pigeons, and 206 pigs.[86]

1948 War

Lajjun was allotted to the Arab state in the 1947 proposed United Nations Partition Plan. The village was defended by the Arab Liberation Army (ALA),[11] and was the logistical headquarters of the Iraqi army. It was first assaulted by the Haganah on April 13, during the battle around kibbutz Mishmar HaEmek. ALA commander Fawzi al-Qawuqji claimed Jewish forces ("Haganah") had attempted to reach the crossroads at Lajjun in an outflanking operation, but the attack failed. The New York Times reported that twelve Arabs were killed and fifteen wounded during that Haganah offensive.[87] Palmach units of the Haganah raided and blew up much of Lajjun on the night of April 15–16.[88]

On April 17, it was occupied by the Haganah. According to the newspaper, Lajjun was the "most important place taken by the Jews, whose offensive has carried them through ten villages south and east of Mishmar Ha'emek." The report added that women and children had been removed from the village and that 27 buildings in the village were blown up by the Haganah. However, al-Qawuqji states that attacks resumed on May 6, when ALA positions in the area of Lajjun were attacked by Haganah forces. The ALA's Yarmouk Battalion and other ALA units drove back their forces, but two days later, the ALA commander reported that the Haganah was "trying to cut off the Lajjun area from Tulkarm in preparation of seizing Lajjun and Jenin..."[89]

State of Israel

On May 30, 1948, in the first stage of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Lajjun was captured by Israel's Golani Brigade in Operation Gideon. The capture was particularly important for the Israelis because of its strategic location at the entrance of the Wadi Ara, which thus, brought their forces closer to Jenin.[90] During the second truce between Israel and the Arab coalition, in early September, a United Nations official fixed the permanent truce line in the area of Lajjun, according to press reports. A 500-yard strip was established on both sides of the line in which Arabs and Jews were allowed to harvest their crops.[13] Lajjun was used as transit place by the Israel Defense Forces to transfer 1,400 Arab women, children and elderly from Ijzim, who then were sent on foot to Jenin.[91]

Kibbutz Megiddo was built on some of Lajjun's village lands starting in 1949. Lajjun's buildings were demolished in the following months.[92]

In November 1953, 34.6 square kilometres (13.4 sq mi) of the lands of Umm al-Fahm were confiscated by the state, invoking the Land Acquisition (Validation of Acts and Compensation) Law, 5713-1953. These included much of the built-up area of Lajjun (at Block 20420, covering 0.2 square kilometres (0.077 sq mi)).[93] It was later planted with forest trees.

In 1992 Walid Khalidi described the remains: "Only the white stone mosque, one village mill, the village health center, and a few partially destroyed houses remain on the site. The mosque has been converted into a carpentry workshop and one of the houses has been made into a chicken coop. The health center and grain mill are deserted, and the school is gone. The cemetery remains, but it is in a neglected state; the tomb of Yusuf al-Hamdan, a prominent nationalist who fell in the 1936 revolt, is clearly visible. The surrounding lands are planted with almond trees, wheat, and barley; they also contain animal sheds, a fodder plant, and a pump installed on the spring of 'Ayn al-Hajja. The site is tightly fenced in and entry is blocked."[92] In 2000 Meron Benvenisti restated the information about the 1943 white mosque.[2] By 2007 it was evacuated and sealed up. [75]

In the 2000s, 486 families from Umm al-Fahm (formerly from Lajjun), through Adalah, motioned to nullify the confiscation of that particular block. The district court ruled against the plaintiffs in 2007,[75] and the supreme court held the decision in 2010.[94]

Lajjun is among the Palestinian villages for which commemorative Marches of Return have taken place, typically as part of Nakba Day, such as the demonstrations organized by the Association for the Defence of the Rights of the Internally Displaced.[95]

In 2013, architect Shadi Habib Allah presented a proposal for a Palestinian village to be rebuilt on Lajjun in areas that are currently a park and inhabited by descendants of its displaced residents. The presentation was made for the "From Truth to Redress" conference organized by Zochrot.[96]

Demographics

During early Ottoman rule, in 1596, Lajjun had a population of 226 people.[53] In the British Mandate census in 1922, there were 417 inhabitants.[97] In the 1931 census of Palestine, the population had more than doubled to 857, of which 829 were Muslims, 26 were Christians, as well as two Jews.[42][98] In that year, there were 162 houses in the village.[11][98] At the end of 1940, Lajjun had 1,103 inhabitants.

The prominent families of al-Lajjun were the Jabbarin, Ghubayriyya, Mahamid and the Mahajina. Around 80% of its inhabitants fled to Umm al-Fahm, where they currently live as Arab citizens of Israel and internally displaced Palestinians.[75]

Culture

Local tradition centered on 'Ayn al-Hajja, the spring of Lajjun, date back to the 10th century CE when the village was under Islamic rule. According to geographers of that century, as well as the 12th century, the legend was that under the Mosque of Abraham, a "copious stream flowed" which formed immediately after the prophet Abraham struck the stone with his staff.[35] Abraham had entered the town with his flock of sheep on his way towards Egypt, and the people of the village informed him that the village possessed only small quantities of water, thus Abraham should pass on the village to another. According to the legend, Abraham was commanded to strike the rock, resulting in water "bursting out copiously". From then, the village orchards and crops were well-irrigated and the people satisfied with a surplus of drinking water from the spring.[41]

In Lajjun there are tombs for two Mamluk-era Muslim relics who were from the village. The holy men were Ali Shafi'i who died in 1310 and Ali ibn Jalal who died in 1400.[13]

See also

- History of Palestine

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

- List of villages depopulated during the Arab-Israeli conflict

- Megiddo church (Israel), possibly dating to the 3rd century and located at ancient Legio

References

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #147. Also gives the cause of depopulation

- ^ a b Benvenisti, 2000, p. 319

- ^ a b Tepper 2003

- ^ Cline, 2002, p.115

- ^ a b c d e f Pringle, 1998, p. 3

- ^ Survey of Palestine (1928–1947). Palestine (Map). 1:20,000. pp. 16/21 Umm al-Fahm, 16/22 Megiddo.

- ^ Palmer 1881, p. 156

- ^ State of Israel, Hydrographic list part 2, items no. 282-286,295.

- ^ a b c Survey of Palestine (1947). Lajjun (Map). 1:2,500. Village Surveys 1946 – via Israel State Archives.

- ^ Survey of Palestine (1928–1947). Palestine (Map). 1:20,000. pp. 16/21 Umm al-Fahm, 16/22 Megiddo, 17/22 Afula.

- ^ a b c Welcome to al-Lajjun Palestine Remembered.

- ^ State of Israel, Hydrographic list part 1, item no. 177 (in list and indices).

- ^ a b c d e Rami, S. al-Lajjun Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine Jerusalemites.

- ^ "Palestine Remembered: Satellite View of al-Lajjun - اللجون, Jinin-جنين". www.palestineremembered.com.

- ^ Nelson (1921) [1913]

- ^ Finkelstein; Na'aman (2005). "Shechem of the Amarna Period and the Rise of the Northern Kingdom of Israel". Israel Exploration Journal. 55 (2): 178. JSTOR 27927106.

- ^ Zertal, Adam (2011). "The Arunah Pass". Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature. pp. 342–356. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004194939.i-370.122. ISBN 9789004210691.

- ^ Zertal, 2016, pp. 51-52, 74

- ^ Gass, Erasmus (2017). "The Deborah-Barak Composition (Jdg 4–5): Some Topographical Reflections". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 149 (4): 326–335. doi:10.1080/00310328.2017.1386439. ISSN 0031-0328. S2CID 165369658.

- ^ Yeivin, Shmuel (1962). הערות טופוגראפיות ואתניות... חמשת בתי-האב הכושיים בכנען [Topographic and ethnic remarks II 5 : the five Cushite clans of Canaan]. Beit Mikra: Journal for the Study of the Bible and Its World (in Hebrew). 7 (2): 31. JSTOR 23499537.

- ^ Redford 2003, p. 109 note 26

- ^ Zissu, Boaz (2006). "Miqwaʾ ot at Kefar ʿOthnai near Legio". Israel Exploration Journal. 56 (1): 57–66. JSTOR 27927125.

- ^ Safrai (1980), p. 223 (note 5)

- ^ Tsafrir, Di Segni & Green, p. 170

- ^ B. Isaac & I. Roll 1982

- ^ Thomsen, p. 77

- ^ David Adan-Bayewitz, Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology, Bar-Ilan University, Question & Response Archived 2019-04-02 at the Wayback Machine (2 December 2013)

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 10b (Mishnah Gittin 1:5)

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, p. 334

- ^ IAA Report: Kefar ‘Otnay and Legio

- ^ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2004, Survey Permit # A-4227

- ^ Gil, 1997, p.42.

- ^ Estakhri and Ibn Hawqal quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.28.

- ^ Mayer, 1932, pp. 100–102

- ^ a b Ibn al-Faqih quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.492.

- ^ Gil, 1997, p.318.

- ^ al-Muqaddasi quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.492.

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p.39.

- ^ al-Muqaddasi quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.301.

- ^ Al-Muqaddasi, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions (Being a translation of "Ahsan al-Taqasim fi Maʿrifat al-Aqalim"), Reading 1994, p. 141 ISBN 1-873938-14-4

- ^ a b le Strange, 1890, p.493.

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p.335

- ^ Popper 1955, p. 16

- ^ Shams al-Dìn al-'Uthmànì cited in Drory 2004, p. 179

- ^ 'Uthmani, Ta'rikh Safad sec. X, in a partial reproduction of the Arabic text in Lewis, 1953 p. 483. Cf. a complete edition in Zakkār, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Ze'evi, 1996, p. 42.

- ^ a b Ze'evi, 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Agmon, 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (2023-05-09). "Lajjun: Forgotten Provincial Capital in Ottoman Palestine". Levant. 55 (2): 218–241. doi:10.1080/00758914.2023.2202484.

- ^ al-Bakhīt, Muḥammad ʻAdnān; al-Ḥamūd, Nūfān Rajā (1989). "Daftar mufaṣṣal nāḥiyat Marj Banī ʻĀmir wa-tawābiʻihā wa-lawāḥiqihā allatī kānat fī taṣarruf al-Amīr Ṭarah Bāy sanat 945 ah". www.worldcat.org. Amman: Jordanian University. pp. 1–35. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ a b The Cultural Landscape of the Tell Jenin Region. Leiden University Open Access, p.29, p.32.

- ^ Heyd, 1960, 110 n.4. Cited in Petersen, 2002, p. 306

- ^ a b Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 190. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 521.

- ^ Ze'evi, 1996, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Ze'evi, 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Maundrell, 1836, p. 97

- ^ Wilson, ed., 1881, vol 2, p. 24

- ^ a b Doumani, 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Abu Dayya, 1986:51, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335

- ^ a b c Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:7-9. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335

- ^ Schumacher, 1908, p. 186

- ^ Robinson, p.328 f.f.

- ^ Finn 1868:229-30, also cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWPII pp. 64-66, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335.

- ^ a b Schumacher, 1908, p. 6

- ^ Petersen, 2001, p. 201

- ^ Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (2024-01-03). "Al-Lajjun: a Social and geographic account of a Palestinian Village during the British Mandate Period". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 1–27. doi:10.1080/13530194.2023.2279340.

- ^ a b c d Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:44. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 335

- ^ Schumacher, 1908, p. 7

- ^ Schumacher, 1908, pp. 186-187

- ^ Fisher, 1929, The Excavation of Armageddon Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, p. 18, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.335

- ^ Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:44-45

- ^ Bronstein, 2004. pp. 7, 16

- ^ a b Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (2024-01-03). "Al-Lajjun: a Social and geographic account of a Palestinian Village during the British Mandate Period". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 8–11. doi:10.1080/13530194.2023.2279340. ISSN 1353-0194.

- ^ a b c d Isabelle Humphries (Autumn 2007). "Highlighting 1948 Dispossession in the Israeli Courts". al-Majdal. No. 35. BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights. Archived from the original on 2018-03-27. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ Bronstein 2004, pp. 8, 13

- ^ Zissu, Boaz; Tepper, Y.; Amit, David (2006). "Miqwa'ot at Kefar Othnai near Legio". Israel Exploration Journal. 56 (1): 57. JSTOR 27927125.

- ^ Bronstein 2004, pp. 6, 7

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 17

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p.55. The seven hamlets were Aqqada, Ein Ibrahim, Khirbet al-Buweishat, Mu'awiya, Musheirifa, al-Murtafi'a, and Musmus.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p.100.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p.150

- ^ Bronstein 2004, pp. 3, 6, 10-11, 12

- ^ Bronstein 2004, pp. 5-6

- ^ Kana´na and Mahamid 1987:48-49. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 335

- ^ Marom, Roy; Tepper, Yotam; Adams, Matthew J. (2024-01-03). "Al-Lajjun: a Social and geographic account of a Palestinian Village during the British Mandate Period". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies: 20. doi:10.1080/13530194.2023.2279340. ISSN 1353-0194.

- ^ Schmidt, Dana Adams. British Repudiate Palestine Charge; Deny Obstructing U.N. Unit - Violence Flares as Big Evacuation Convoy Starts New York Times. 1948-04-14. The New York Times Company.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 242

- ^ Schmidt, Dana Adams. Jews press Arabs in Pitched Battle in North Palestine; Seize 10 Villages and 7 Guns in Mishmar Haemek Area - Repel Counter-Attacks UN Session Opens Today, Special Assembly to Gather at Flushing Meadow in Gloom - Zionist Rejects Truce Pitched Battle Rages in Palestine Jew Press Arabs in North Palestine New York Times. 1948-04-16. The New York Times Company.

- ^ Tal, 2004, p. 232.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 439

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, pp. 336-337

- ^ See GIS map by the Survey of Israel: [1].

- ^ "Israeli Supreme Court Rules that Lands Confiscated in Lajoun from 486 Arab Families in 1953 for "Settlement Needs" will not be Returned to Them". Adalah. 2010-01-12.

- ^ Charif, Maher. "Meanings of the Nakba". Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – palquest. Retrieved 2023-12-05.

- ^ Pessah, Tom (2013-10-05). "At annual conference, Palestinians and Israelis turn 'return' into reality". +972 Magazine. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table IX, Sub-district of Jenin, p. 30

- ^ a b Mills, 1932, p. 69

Bibliography

- Agmon, Iris (2006). Family & Court: Legal Culture and Modernity in Late Ottoman Palestine. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630623.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Bronstein, Eitan, ed. (2004). Remembering al-Lajjun (in Arabic and Hebrew). Zochrot. [Includes the recollections of six former villagers.]

- Cline, E.H. (2002). The Battles of Armageddon: Megiddo and the Jezreel Valley from the Bronze Age to the Nuclear Age. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06739-7.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Doumani, B. (1995). Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20370-4.

- Drory, Joseph (2004). "Founding a New Mamlaka: Some Remarks Concerning Safed and the Organization of the Region in the Mamluk period". In Michael Winter; Amalia Levanoni (eds.). The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian Politics and Society. BRILL. pp. 163–187. ISBN 90-04-13286-4.

- Fisher, C.S., 1929, The Excavation of Armageddon Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, Oriental Institute Communications 4, University of Chicago Press

- Gil, M. (1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59984-9.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Heyd, Uriel (1960): Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552-1615, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Cited in Petersen (2002)

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Isaac, B.; Roll, I. (1982). Roman Roads in Judaea, vol 1: The Legio-Scythopolis Road. BAR International Series (141). Oxford. doi:10.30861/9780860541721. ISBN 978-1-4073-2861-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kana´na, Sharif; Mahamid, ´Umar (1987). القرى الفلسطينية المدمرة : اللجون [Destroyed Palestinian villages (6): Lajjun]. Destroyed Palestinian villages (in Arabic). Vol. 6. Bir Zeit University, Center for Research and Documentations. hdl:20.500.11889/5221.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Lewis, B. (2009). "An Arabic Account of the Province of Safed—I". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 15 (3). Shams al-Din al-'Utmani, fl. 1372-1378: 477–488. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00111449. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162542040.

- Maundrell, H. (1836). A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: At Easter, A. D. 1697. Boston: S.G. Simkins.

- Mayer, L.A. (1932). "A hoard of Umayyad Dinars from El Lajjun". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 4: 100–103.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Nelson, Harold Hayden (1921) [1913]. The Battle of Megiddo. Thesis (Ph.D.)—University of Chicago.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Popper, William; Ibn Taghribirdi (1955). Egypt and Syria under the Circassian sultans, 1382-1468 A.D. : systematic notes to Ibn Taghrî Birdî's chronicles of Egypt. University of California publications in Semitic philology. University of California Press.

- Pringle, D. (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- Ptolemy (2001). Berggren, J. Lennart & al. (ed.). Ptolemy's Geography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09259-1.

- al-Qawuqji, F. (1972): Memoirs of al-Qawuqji, Fauzi in Journal of Palestine Studies

- "Memoirs, 1948, Part I" in 1, no. 4 (Sum. 72): 27-58., pdf-file, downloadable

- , pdf-file, downloadable

- Redford, D.B. (2003). The Wars in Syria and Palestine of Thutmose III. Brill. ISBN 9789004129894.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Safrai, Z. (1980). Boundaries and Government in the Land of Israel (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schumacher, G.; Watzinger, C. (c. 2015) [German original, 1908]. Tell El-mutesellim: Report of the Excavations Conducted From 1903 to 1905 With the Support of His Majesty the German Emperor and the Deutsche Orient-gesellschaft From the Deutscher Verein Zur Erforschung Palästinas. Translated by Martin, Mario. The Megiddo Expedition, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. The edition follows the same pagination the German publication at Tell el Mutesellim; Bericht über die 1903 bis 1905... Leipzig, Haupt. 1908..

- State of Israel, "Hydrographic list of the map of Israel", [Government Naming Committee decisions, in Reshumot]:

- רשימון הידרוגרפי של מפת ישראל, חלק ראשון: רשימון הנחלים [Hydrographic list of the map of Israel, part 1: list of streams] (PDF), Yalkut HaPirsumim, May 20, 1958

- רשימון הידרוגרפי של מפת ישראל, חלק שני: רשימון המעינות [Hydrographic list of the map of Israel, part 2: list of springs] (PDF), Yalkut HaPirsumim, April 9, 1959

- Tal, D. (2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5275-X.

- Tepper, Y. 2003. Survey of the Legio Area near Megiddo: Historical and Geographical Research. MA thesis, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv.

- Thomsen, Peter (1966). Loca Sancta, Hildesheim

- Tsafrir; Di Segni; Green (1994). Tabula Imperii Romani, Iudaea – Palaestina, Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods: Maps and Gazetteer. Jerusalem. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilson, C.W., ed. (c. 1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. Vol. 2. New York: D. Appleton.

- Zakkar, Suhayl; al-'Uthmani, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Husayni (2009). تاريخ صفد : مع ملاحق عربية ولاتينية مترجمة تنشر للمرة الأولى [The history of Safad: with Arabic and Latin supplements translated for the first time]. Damascus: Dar al-Talwin. OCLC 776865590 – via Rafed.

- Ze'evi, Dror (1996). An Ottoman Century: The District of Jerusalem in the 1600s. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2915-6.

- Zertal, A. (2016). The Manasseh Hill Country Survey. Vol. 3. Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004194939.i-370.122. ISBN 9789004312302.

External links

- Welcome To al-Lajjun, palestineremembered.com

- Lajjun, from Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 8: Wikimedia commons

- Al-Lajjon from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Al- Lajjun from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center