Shah-Armens

Shah-Armens Ahlatşahlar | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1071–1207 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ahlat | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Turkish, Armenian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Establishment | 1071 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1207 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

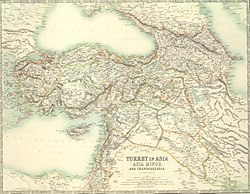

The Shah-Armens[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][excessive citations] (lit. 'Kings of Armenia', Turkish: Ermenşahlar), also known as Ahlatshahs (lit. 'Rulers of Ahlat', Turkish: Ahlatşahlar) or Begtimurids, was a Turkoman Sunni Muslim Anatolian beylik of the Seljuk Empire, founded after the Battle of Manzikert (1071) and centred in Ahlat on the northwestern shore of the Lake Van. This region comprised most of modern-day Bitlis and Van, and parts of Muş provinces.

History

The dynasty is sometimes also called Sökmenli in reference to the founder of the principality, Sökmen el-Kutbî, literally "Sökmen the Slave", one of the commanders of the Alp Arslan. The Ahlatshah Sökmenli should not be confused with the Sökmen, which ruled in Hasankeyf during approximately the same period. Another title Sökmen and his descendants assumed, as heirs to the local Armenian princes according to Clifford Edmund Bosworth, was the Persian title Shah-i Arman ("Shah of Armenia"), often rendered as Ermenshahs. This dynastic name, which the rulers adopted, was established through the "ethnic make-up and political history" of the region they ruled, which was primarily Armenian.[13]

The Beylik was founded by the Sökmen el-Kutbî who took over Ahlat (Khliat or Khilat) in 1100. Ahlatshahs were closely tied to Great Seljuq institutions, although they also followed independent policies like the wars against Georgia in alliance with their neighbours to the north, the Saltukids. They also acquired links with the branch of the Artuqids based in Meyyafarikin (now Silvan), becoming part of a nexus of principalities in Upper Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia.

The Ahlatshahs reached their brightest period under the fifty-seven-year reign of Sökmen II (1128–1185). He was married to a female relative (daughter or sister) of the Saltukid ruler Saltuk II.[14] Since Sökmen II was childless, the beylik was seized by a series of slave commanders after his death. In 1207, the beylik was taken over by the Ayyubids, who had long coveted Ahlat. The Ayyubids had come to the city at the invitation of people of Ahlat after the last Sökmenli ruler was killed by Tuğrulshah, the ruler (melik) of Erzurum on behalf of the Sultanate of Rum and brother of Sultan Kayqubad I.

The Ahlatshahs left a large number of historic tombstones in and around the city of Ahlat. Local administrators are currently trying to have the tombstones included in UNESCO's World Heritage List, where they are currently listed tentatively.[15]

Gallery

- Ahlat Gravestones

- Ahlat Gravestones

- Ahlat Gravestone

- Ahlat gravestone Detail

- Ahlat Gravestone

- Ahlat Gravestone

- Ahlat Gravestone

- Ahlat Gravestone

List of Shah-Armens

| Reign[16] | Name | Son of | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1100–1111 | Sökmen I | ||

| 1111–1127 | Zahireddin İbrahim | Sökmen | |

| 1127–1128 | Ahmet | Sökmen | |

| 1128–1185[17] | Nasireddin Muhammed Sökmen II | Ibrahim | Died without heirs. |

| 1185–1193 | Seyfettin Beytemür | The beys from then on were Ghilmans. | |

| 1193–1198 | Bedreddin Aksungur | ||

| 1198 | Şücaüddin Kutluğ | ||

| 1198–1206 | Melikülmansur Muhammed | Beytemür | |

| 1206–1207 | Izzeddin Balaban |

See also

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

References

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen «Armenia: A Historical Atlas», p. 129:

As the Georgians gradually became masters of northern Armenia, the south-central parts of the country passed under a Turkish dynasty calling itself the Shah-Armen (1100-1207), a title tantamount to "king of Armenia." Centered at Khilat (Arm. Xlat'; Tk. Ahlat), on the northwest shore of Lake Van, the political situation of the Shah-Armen state changed greatly during the twelfth century in regard to what these shahs held and what was merely subject to them through ties of vassalage.

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian. The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times Vol. I. Chapter 10 «Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods» by Robert Bedrosian. pp. 241-271:

The Seljuk Empire of Iran, proclaimed in 1040, lasted little more than one hundred years. It, in turn, was destroyed by another wave of Turkic nomads, the Kara Khitai. In Asia Minor, a variety of states arose during the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, virtually independent of Iran and often inimical toward each other. The most important of these were the Danishmendid state centered at Sebastia/Sivas, the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (or Iconium) centered at Iconia/Konia and the state of the Shah-Armens centered at Khlat.

- ^ George A. Boumoutian «A Concise History of the Armenian People», p. 109:

The Byzantines, who had destroyed the Bagratuni Kingdom a few years earlier, now lost it to the Turks. Many cities were looted, churches destroyed, trade disrupted and some of the population forcibly converted or enslaved. A number of dynasties such as the Danishmendids, Qaramanids, Shah-Armans, and the Seljuks of Rum emerged in Anatolia.

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica, article: ARMENIA AND IRAN vi. Armeno-Iranian relations in the Islamic period:

This condition became more accentuated especially during the period of the disintegration of the Saljuq empire, when the atabegs who had assumed great power in border districts, became autonomous. The Danishmandids ruled in Lesser Armenia and Cappadocia 1005-06. Further in the west, in 1077, the Saljuq sultanate of Rum was established. From 1100, in the center of Xlaṭʿ (Aḵlaṭ) in the western part of Greater Armenia, the Sukmanids ruled, calling themselves “Šāh-e Arman”.

- ^ Joseph Strayer «Dictionary of the Middle Ages» vol. 1, 1982. P. 505:

Despite the survival of various minor principalities, the disappearance of the kingdom of Ani marked the end of the last major political unit in Greater Armenia for centuries to come. Nevertheless, some portions of the region recovered following the Seljuk conquest and the final withdrawal of Byzantium. Ani generally prospered under Shaddadid rule (1072–1199) despite, repeated Georgian attacks, as did Xlat under that of the "Philochristian" Armenized Seljuk dynasty of the Sah-i Armen (1100-1207).

- ^ Vahan M. Kurkjian «A History of Armenia» p. 168:

It was not long before two Ortokid dynasties were created in Armenia and Kurdistan, the former by Sokman, the Shah-Armen (or "King of Armenia") and the other by Il-Ghazi.

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth "The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual". Article «The Shâh-i Armanids», p. 197.

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5 «The Saljuq and Mongol Periods» pp. 111–112:

p. 171:The role of the ghulam commanders and the Turkmen begs becomes very prominent in this period, and local Turkmen dynasties begin to form: the sons of Bursuq in Khuzistan; the Artuqids in Diyarbakr; at Khilat the Shah-Armanids, descendants of Isma'Il b. Yaquti's ghulam Sukman al-Qutbl; and shortly afterwards the Zangids, descendants of Aq-Sonqur, in Mosul.

In Armenia the Shah-Armanids, descendants of the ghulam Sukman al-Qutbi, were frequently involved in the politics and warfare of Azarbaijan, tending to take the side of Aq-Sonqur II against the Eldigiizids. But when Nasr al-Din Sukman died without an heir in 581/1185, a bloodless struggle for power took place between Pahlavan b. Eldigiiz, who had married a daughter to the aged Shah-Arman in order to acquire a succession claim, and the Ayyubid Saladin. In the end, Pahlavan took over Ahlat, whilst Saladin annexed Mayyafariqin in Diyarbakr, a possession of the Artuqids of Mardin which had been latterly under the protectorship of the Shah-Arman. Mosul and the Jazireh remained under Zangid rule, although the relentless advance of Saladin into the Jazireh posed a serious threat to the Zangids, driving the last Shah-Arman and the atabeg cIzz al-Din Mas'iid b. Qutb al-Din Maudud into an alliance against Ayyubid aggression. After the death of Saladin in 589/1193, the Zangids recaptured most of the towns and fortresses of the Jazireh.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 9, BRILL 1997. P. 193, article: «Shah-i Arman»:

SHAH-I ARMAN, "King of the Armenians", denoted the Turcoman rulers of Ahlat [q.v.] from 493/1100 to 604/1207.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, vol 20, 1961 by Harry S. Ashmore. P. 310:

He also gained the city of Khelat with dependencies that in former times had belonged to the Shah-i-Armen, but shortly before had been taken by Jalal ud-Din; this aggression was the cause of the war just mentioned.

- ^ Cyrille Toumanoff «Studies in Christian Caucasian history» Georgetown University Press. P. 210:

But the Mamikonids succeeded in remaining sovereign, under vague Byzantine suzerainty, in the southwestern part of Taraun, round the fortress-city of Arsamosata, and in the neighboring Arzanenian land of Sasun, i.e., in the middle valley of the Arsanias, until their dispossession by the Shah-Armen in 1189/1190 and their migration to Armenia-in-Exile, in Cilicia.

- ^ Austen Henry Layard «Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon». Gorgias Press LLC, 2002. P. 28:

Shah Armens, i.e. Kings of Armenia, was a title assumed by a dynasty reigning at Ahlat, founded by Sokman Kothby, a slave of the Seljuk prince, Kotbbedin Ismail, who established an independent principality at Ahlat in A.D. 1100, which lasted eighty years.

- ^ Pancaroğlu 2013, p. 54.

- ^ Cahen, p. 107.

- ^ "Tentative World Heritage Sites". UNESCO.

- ^ Bosworth 2004, p. 197.

- ^ Peacock & Yildiz 2013, p. 54.

Sources

- Claude Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey

- Pancaroğlu, Oya (2013). "The House of Mengüjek in Divriği: Constructions of Dynastic Identity in the Late Twelfth Century". In Peacock, A.C.S.; Yildiz, Sara Nur (eds.). The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1848858879.

External links

- (limited preview) Clifford Edmund Bosworth (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2137-7.