Affair of the Cards

| Part of a series on |

| Freemasonry |

|---|

|

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Topics |

|

|

The Affair of the Cards (French: Affaire des Fiches), sometimes called the Affair of the Casseroles,[a] was a political scandal which broke out in 1904 in France, during the Third French Republic. It concerned a clandestine political and religious filing operation set up in the French Army at the initiative of General Louis André, Minister of War, in the context of the aftermath of the Dreyfus affair and accusations of anti-republicanism made by leftists and radicals against the Corps of Officers in the French Army (which was at the time the largest land army in Europe) who accused it of being a final redoubt of conservative Catholic and royalist individuals within French society.

From 1900 to 1904, the prefectural administrations, the Masonic lodges of the Grand Orient de France and other intelligence networks established data sheets on officers, which were sent to General André's office in order to decide on which officers would be allowed to receive promotions and advance up the military hierarchy, as well as be awarded decorations, and who would be excluded from advancement. These secret documents were preferred by General André to the official reports of the military command; this allowed him to set up a system whereby the advancement of republican, masonic and "free-thinking" officers was ensured and those who were identified as nationalist, Catholic or suspected to be sympathetic to any of the various strands of royalism would be hampered. For the Grand Orient and the cabinet of André, the purpose was to ensure the loyalty of the Officer Corps to the ruling regime of the Third Republic.

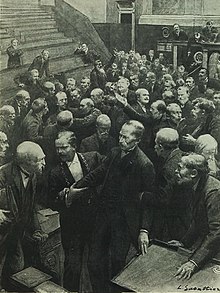

The scandal was unveiled to the public on 28 October 1904, when Jean Guyot de Villeneuve challenged the government in the Chamber of Deputies and revealed the filing system established by General André and the Grand Orient, producing in support of his accusations files which had been purchased from Jean-Baptiste Bidegain, deputy of the secretary-general of the Grand Orient. The Minister at first denied having any knowledge of these actions, but during the meeting of 4 November 1904, Guyot de Villeneuve produced a document which directly incriminated André; the meeting was stormy and the nationalist deputy Gabriel Syveton slapped the Minister of War, triggering a tussle on the floor.

The scandal had a major significance in French politics. The twists and turns and revelations of the affair followed one another for several months, while the press regularly published the files in question. Despite the support of Jean Jaurès of the French Socialist Party and the republican Bloc des gauches, the Émile Combes government collapsed on 15 January 1905, due to the pressure from the affair. The Maurice Rouvier cabinet, which succeeded him, formally condemned the system, pronounced symbolic sanctions and pursued a policy of rehabilitation. Nevertheless, the card system continued after 1905, no longer based on spying from the Grand Orient but on prefectural information and backed by the practice of political pressure. In 1913, the Minister of War Alexandre Millerand put an end to it definitively.

This political filing system, in addition to causing a certain moral and political crisis within Dreyfusard circles, which were divided on the priority to be given between the defense of the Third French Republic and the protection of freedom of conscience for all (including those they disagreed with), also weakened the French military high command, due to more than ten years of discrimination in the advancement of officers, which had consequences that were difficult to assess during the first months of the First World War.

Background

Dreyfus affair

Since the establishment of the French Third Republic, the French Army had kept itself relatively aloof from the political struggles which pitted the monarchists against the partisans of the Republic, a confrontation which ended in the latter's final victory in 1879 with the change of the Senate. Although it did not allow itself to be tempted by the adventurism of a coup d'etat, the officer corps of the Army was nonetheless seen as anti-republican, a vision which was reinforced by the outbreak of the Dreyfus affair. The refusal of the military high command to let the truth come out as well as the haughty attitude of the officers called upon to testify at Dreyfus' second trial led the Republicans to make accusations. The Republicans described the army as a "state within a state" where scions of conservative families (ethnically French and religiously Catholic) could make successful careers when other fields were closed to them.[1][2] Also, since the beginning of the Dreyfus affair — even since the Boulangist crisis — the right had begun to embrace nationalism and the defense of the Army, while the left placed itself under the banner of an anticlericalism informed by Continental Freemasonry and — at least in part — anti-military sentiment.[3]

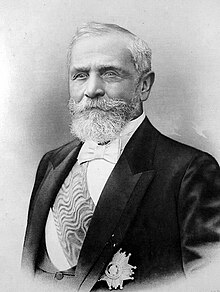

Nationalist agitation in 1899, contemporary with the Dreyfus affair, convinced the left that the Republic was in danger. The attempt of the poet Paul Déroulède who, betting on the anti-Republican sentiments of the Army, tried unsuccessfully to tried to encourage General Gaudérique Roget's troops to march on the Élysée Palace during Félix Faure's funeral on 23 February 1899, made the republicans fear for the worst. Also, the "government of Republican Defense" of Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau and then the cabinet of Émile Combes (himself a Freemason,[4][5] belonging to the Grand Orient de France)[6] sought to entrench the regime by proceeding with a "purification" of any institutions which were considered anti-Dreyfusard, the foremost target among which was the Army.[7]

In parallel with the fallout from the Dreyfus affair, the Combes cabinet, cemented by Freemasonry (in particular the Grand Orient de France) and spurred on by the Radical Party,[8] launched an offensive against the Catholic Church in France. The Combes government expelled religious orders from French territory, and prepared the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, which was the strongest anticlerical measure of the early 20th century.[9] This move against Catholicism in French society, under the banner of separation, was closely linked to the Affair of the Cards: the religious convictions of Catholic officers were considered as proof of hostility to the Republic. President Émile Loubet opposed Combes on the advisability of this law. Finally, it was with the aim of avoiding separation that Guyot de Villeneuve exposed the scandal of the files.[10]

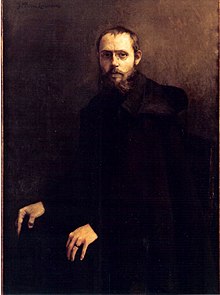

Previous Gambetta papers

In the first years of the French Third Republic, secret files on the officers of the French Army had already been collected with the assistance of Freemasonry.[11][12] These “Gambetta papers”, named after the radical politician Léon Gambetta — who had them constituted for the use of the Republicans — contained notes on the military skills and political convictions of the main officers, in two files.[11] The first, completed in the first days of 1876, reviewed the entire Army corps, division by division.[11][13] The second, compiled in the fall of 1878, reviewed the careers and political tendencies of the officers of the Ministry of War, the School of War, the General Staff of the Army and the Grandes Military Schools.[11][14]

These files, established by a republican intelligence network supported by Masonic lodges, thus already pointed — well before the Affair of the Cards — to the monarchist officers thought to present a danger to the Republic.[11] After the accession to power of the Republicans, a certain number of generals were dismissed from their commands on the basis of these files, in order to make the military institution more malleable in the hands of the new regime. It was also the dismissals within the Army that provoked the anger and the resignation of Marshal Patrice de MacMahon, President of the Republic from 1873 to 1879.[15]

Nine years later, during the Boulangist crisis, Edmond Lepelletier, founder of the Les Droits de l'Homme lodge under the Grand Orient de France, proposed to set up committees, directly supported by the lodges and the Society of Human Rights and of the Citizen, who would have been responsible for reporting "the servants of the State disposed to betray and the maneuvers of hiring, corruption, intimidation of monarchists, clerics and their new allies, the Boulangists". But this idea was opposed by the director of La Chaîne d'union, Esprit-Eugène Hubert (the published review of the Grand Orient de France).[16]

Implementation of the card system

Appointment of General André to the Ministry of War

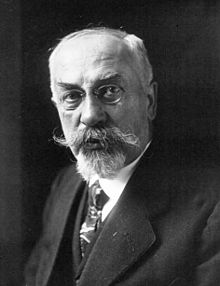

Following the resignation in May 1900 of General de Galliffet, the President of the Council Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau appointed — on the advice of Henri Brisson — General Louis André to succeed him at the Ministry of War. This soldier, from the Polytechnic School, was known for his fervent republicanism and his "doctrinaire" character.[17] His mission was to continue the task of his predecessor, namely to liquidate the last turmoil of the Dreyfus affair and to continue with "republicanization" of the Army at lightning fast speed.[18]

To achieve this, Gaston de Galliffet changed the de-centralised methods of advancement in rank in the Army: on the 9 January 1900, he issued a decree to abolish the regional advancement commissions which decided autonomously on the advancement table. Indeed, Galliffet suspected the military high command of partiality; by setting up arms commissions and a higher commission to make proposals, this left the War Ministry full latitude to make a final decision.[18]

These arms commissions having in their prerogatives the exclusion without recourse of the officers considered too mediocre, General André decided on 15 March 1901 to abolish arms commissions to allow the ministry complete freedom of choice. The system set up by André outraged part of the hierarchy, including General Hippolyte Langlois, who said in the Revue des Deux Mondes:[18]

[It is established] in each army corps, lists containing all the candidates who meet the legal conditions for advancement by choice. The different hierarchical heads indicate on these lists, in special columns, the number of preference which they grant to each subject; when an officer is judged incapable of taking the choice, the chief places the words “adjourned” before his name. From then on there was no longer and there is no longer any brake on arbitrariness; each year we see the minister oust the most appreciated officers from the roll and choose not only those who are presented last, but even those who are postponed! What disdain for the command!

Indeed, General André and his cabinet were determined to promote the advancement of republican officers to the detriment of nationalists and monarchists; persuaded that the military command was being overrun by reactionaries, they were suspicious in principle of reports from the military hierarchy. Paying as much attention to political opinions as to military qualities, General André sought an alternative source of information on officers, and in particular on all subaltern officers who, not enjoying public stature, were only identified in detail in the reports of their superior offices. Having addressed the prefects, André considered their information insufficient and considered their assessments too influenced by local circumstances. Pushed by General Alexandre Percin, his chief of staff, General André then turned to the Grand Orient de France in order to inform him about the political opinions of the officers by clandestine means.[18]

After the triumph of the Bloc des gauches in the legislative elections of 1902, General André was returned to the cabinet of Émile Combes, with whom he initially had good relations and who saw him as an executor of his policy of anti-clericalism in all areas of society.[17] On 20 June 1902, in a circular addressed to the prefects, Combes summed up the action he intended to take in the public service: “Your duty requires you to reserve the favors you have available only to those of your citizens who have given unequivocal proof of loyalty to republican institutions. I have agreed with my cabinet colleagues that no appointment, no advancement of civil servant belonging to your department occurs without your having been consulted beforehand ” . The card system, a rigorous application of this methodology, therefore continued.[19]

Relations between André's cabinet and the Grand Orient

On the advice of General Percin — his chief of staff, in whom he has complete confidence[17] — André met with Senator Frédéric Desmons, a Calvinist pastor and Grand Master of the Grand Orient of France, the most influential Masonic body in the country. This meeting, which took place at a date difficult to specify — probably between the end of 1900 and the beginning of 1901 — aroused the enthusiasm of Desmons: the latter, eager to fight Catholic "clerical reaction", declared himself in favor of the collection by the provincial lodges of information on the officers and their transmission to the office of the Minister of War, though clandestine spying means. The lodges, present in many garrison towns, would indeed serve as a detailed intelligence service.[18]

Following these preliminary contacts, André's military cabinet and the Grand Orient maintained ongoing relations, managed on the one hand by Narcisse-Amédée Vadecard, Secretary-General of the Grand Orient, and on the other hand, by the Captain Henri Mollin, orderly officer of the minister and a fellow freemason. According to Guy Thuiller, Desmons having had the principle of carding validated by the Council of the Order of the Grand Orient, the masonic lodges were invited to give their active support to Vadecard.[20] However, historians of Freemasonry, Pierre Chevallier (historian)[21] and Patrice Morlat have claimed that the Council of the Order was not consulted, only the office was and gave its approval. The latter then requested the most reliable "venerable" freemasons to send the information back to the Secretariat.[22]

Captain Mollin — who enjoyed almost exclusive relations with the Grand Orient[18] — was responsible for the file system within the military cabinet. Of a "touchy" character and sometimes being accused of a persecution complex, he maintained difficult relations with his superior, General Percin. The latter however left him in charge of the filing service, which was quite sensitive in nature.[23] When Mollin was on leave, he was replaced by two other Freemasons from the cabinet, Lieutenant Louis Violette and Captain Lemerle.[24]

The other officers of the cabinet, informed of the registration system by the Grand Orient, were divided on the advisability of such methods. Thus, Captain Charles Humbert, supported by Commander Antoine Targe, was opposed to the system of advancement by cards, and especially to denunciation between officers. Supported by the head of the civil cabinet, Jean Cazelles, warned the Minister the dangers of these practices and the damage that could be caused by their revelation. Faced with the lack of success of their approach, Targe and Humbert went so far as to contact in 1902 the new president of the Council of the Order of the Grand Orient, Auguste Delpech, to convince him to give up filing. These steps earned them the hostility of Mollin, Lemerle, Violette and Commander Jacquot, and the latter endeavored to discredit them with the minister, sometimes by calumny.[25]

In July 1902, an incident linked to Freemasonry allowed them to settle their quarrel: the commander of the military school of Flèche, Lieutenant-Colonel Terme, being the subject of intrigues, Captain Humbert — in charge of the direction of the Infantry — conducted an investigation, entrusted to General Castex. Having read the general's report, he concluded:[25]

Under the most cowardly pretexts, in a spirit of envy and jealousy, Commander X and Lieutenant Y waged a terrible campaign against their leader, Colonel Terme. They destroyed at La Flèche any spirit of discipline, practiced anonymous denunciation in all that it is most ashamed of and, feeling supported by certain politicians belonging to the lodges of which they are part, they have braved everything for more than six months. Such officers do the greatest damage to the republican cause in the army, for which we fight here with the last energy, and it is unfortunate that prime positions are kept by men whose position to be given would be retirement and retirement. no activity. Reactionary and clerical officers must, when they fail in their duty, be struck with the last energy, but the black sheep, and there are many that have crept into our ranks for quite some time, must also be struck with equal energy. I therefore ask and this in the interest of the army and justice, to put Commander X in retirement and to approve the other measures proposed by the leadership of the infantry.

This report triggered strong protests from the aforementioned Freemasonic-aligned politicians (though their names were censored in the report) and Humbert's enemies. André's arbitration was final: the head of the civil cabinet, Cazelles, was made to leave his post and Humbert was expelled from the military cabinet. Camille Pelletan, Minister of the Navy offered to welcome Humbert into his own cabinet, but André categorically refused this. This maneuver allowed the Minister to silence the dissenting voices within his cabinet and it greatly served him with Republican parliamentarians hostile to his methods.[25]

Practical operation

Grand Orient intelligence reports

By decision of the office of the Council of the Order of the Grand Orient de France,[26] it was decided that the Worshipful Master from each local Masonic Lodge would be required to respond to information requests about individuals in their locality, sent out from the Secretary-General of the Grand Orient de France. These requests came from lists of "suspects" drawn up by Henry Mollin (or where applicable, by Violette and Lemerle) and sent to Narcisse-Amédée Vadecard and his assistant Jean-Baptiste Bidegain.[24] These instructions were not put in the official public journals, in order to help maintain the secrecy of this enterprise. In addition to the Worshipful Masters, other Freemasons holding political office and considered dependable were contacted directly.[26]

The vast majority of Worshipful Masters diligently carry out the inquiries requested by Vadecard. Nevertheless, some isolated lodges expressed their opposition, based on article 19 of the Constitution of the Grand Orient, which stipulated: “[The brothers] must refrain from all debates on acts of civil authority and any Masonic intervention in disputes between political parties”; this would appear to have included the Worshipful Masters of Masonic Lodges at Périgueux, Rochefort and Saint-Jean-de-Luz who turned down requests to provide reports.[24] Freemasons from other obediences also participated in gathering intelligence and providing reports; one of the two main writers of intelligence reports providing notes on Catholic and nationalist French Army officers was Bernard Wellhoff, Worshipful Master of the Masonic Lodge La Fidélité belonging to the Grand Lodge of France (representatives of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in France). Wellhoff, scion of a noted Alsatian Jewish family, would in the following years become Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of France.[27]

The intelligence files sent to the Ministry of War listed the political opinions and presumed skills of thousands of officers. The religious and philosophical convictions of their families are also mentioned. In instances where the "suspect" professed to be apolitical or the reporting Freemason was unable to pin down his political beliefs categorically, a number of derisory personal notes which pointed against the individual were indicated, such as "Attends the Mass", "Has his children educated by religious brothers",[28] "Reactionary and convinced Catholic",[29] "Made a fool of himself four years ago when he fell to his knees in the passage of a procession",[30] "When you have such a name (in particular), you cannot be a Republican",[31] "Close friend of the Bishop", "Accepted three years ago to represent a titled Lieutenant in a duel with the editor of a republican newspaper”, “Gathered at his table a Capuchin following the closure of the convent of Castres”[32] or in defense as “Devoted to the government”.[28]

At the Ministry of War, these intelligence reports compiled by the Freemasons were used to classify officers in two files: Catholic and nationalist officers — generally to be excluded from promotions - were placed in the "Carthage"[28] category (the name recalling the word of Cato the Elder, Carthago delenda est: "Carthage must be destroyed"),[33] the republican and masonically aligned officers — whose career André cabinet sought to accelerate — found their place in the "Corinth"[28] category (a reference to Non licet omnibus adire Corinthum: "Not everyone can go to Corinth").[33] The intelligence reports began to be compiled when General André arrived at the Ministry of War and initially only contained the officers that the Minister had known during his career personally or that he had heard of — little more than 800 reports.[34] The historian Serge Berstein has counted a total of 18,818 intelligence files written on officers as a result of the Grand Orient's activities between 1 September 1901 and 30 October 1903, a number lower than the total number of files established during the operation of the system, which began at the end of 1900 and stopped when the scandal was revealed at the end of 1904.[30] At the time of this registration system, the total number of active French officers was around 27,000.[34]

The historian Guy Thuillier has reported the writings of General Émile Oscar Dubois, head of the military house of the President of the Republic Émile Loubet, when he relates the impact of the card system on advancement within the French Army:[35]

Never has parliamentary or Masonic action been exercised so widely and slyly; never was denouncement more in honor in the cabinet of the rue Saint-Dominique; on the observation or denunciation of a Brother, on the recommendation of a Venerable, an officer is excluded from the advancement table or added to this table. The intrigues are pushed to such a point that even old Freemasons in the Eastern regions, I was told in recent days, are disgusted to see young officers entering the lodges only to satisfy their ambition. What leaven of hatred and discord will have left in the Army and in the Navy this disastrous trio: Combes, André, Pelletan!

For Guy Thuillier, the major error in the intelligence reporting system made by the Grand Orient was to have tried to gather information on all the officers, in a totalitarian manner, from the lowest Lieutenant up to the highest Generals of Divisions; the consequence of this abundance of files being that, most often without cross-checking, the collection of information on private life of the offices or information of questionable relevance to the issue at hand, for instance comments such as: "He is a perfect satyr, little girls from twelve to thirteen are good for him", "Just like the angels, he has no sex”, “His inscription on the board paid for the services rendered by his wife to General D”.[36]

Prefectural administration reports

In France, the local prefecture administrations were, in theory, the main source of government information about military officers. However, in practice, information from the Grand Orient had more weight in the decisions of the Ministry of War. The systematic registration by Freemasonry preceded that which was set up by the prefectural administration following the circular of 20 June 1902.[19]

For promotions, desirable transfers or military decorations, the Minister of War transmitted to the local prefects — directly or through the services of the Minister of the Interior — the names of the officers in the running; the survey covered "the political attitudes and feelings of these candidates" as well as the schools attended by their children (the significant question being whether their children attended a Catholic school or a liberal secular school).[37] The prefects also transmitted their opinions of the officers' families, their respect for civil authority as well as their degree of collaboration in the regime's law enforcement missions.[38] These inquiries were concluded with a personal opinion from the Prefect who decided on the follow-up path to be taken after the proposals. However, the postponement request could only be made "with caution and only for very serious reasons," according to the Combes circular. The investigations were carried out by the local police, the special commissioners in charge of counter-intelligence and the municipal police, who were the main informants of the prefectural administration.[38]

The zeal shown by the prefects to respond to government requests varied greatly according to the departments; the administrative oversight of the military seemed exaggerated to some, while others, convinced that the Army was factious, responded eagerly. In 1902, Mollin wrote to Vadecard: "as some prefects are more Mélinists than radicals, they will naturally be inclined to mark [the officers] as very correct, even if they are not at all".[27] In addition, the quality of the information sometimes left much to be desired: many references were imprecise, the recently transferred officers were unknown to the police services,[39] and the prefects themselves only moved in the circles of the senior officers. Xavier Boniface also notes that the tone of the prefectural files was more moderate and less militant than that of the Grand Orient files.[40]

Parallel networks

In addition to the registrations carried out by the Grand Orient Masonic lodges and the prefects, two other networks informed General André's office of the political opinions of the officers. The first was that of the Solidarité des Armées de terre et de mer, a company created in 1902 and bringing together Freemasonic officers "without any distinction of rites". In theory controlled by the Secretary-General of the Grand Orient, it was in fact under the control of its president, Commander Nicolas Pasquier, commander of the military prisons of Paris — he was appointed to this post by André in 1901 — and to this title director of the Cherche-Midi prison. Under his leadership, this company became a veritable intelligence agency, with the Freemasonic officers carried out a vigilant surveillance of the political convictions of their comrades. This information was compiled in files by Commander Pasquier, sometimes at the request of the Grand Orient, sometimes on his own initiative. They were then communicated to the Ministry of War through the Grand Orient.[41] The commander specialised in particular in the supervision of personnel in military schools. 180 files were written personally by Pasquier which would be published to the general public when the scandal eventually broke.[42] According to Jean-Baptiste Bidegain (whose accuracy Thuillier doubts), Pasquier's network would have produced 3,000 files in total.[41]

The second secret network was the one owned by General André's military cabinet. Bernard André, the nephew of the Minister of War, was in particular in charge of analysing anonymous denunciations, very numerous, which were sent to the ministry by both officers and civilians. On the other hand, several orderly officers had informants. From 1901, Captain Lemerle — already the understudy of Captain Mollin for relations with the Grand Orient — undertook to structure a "network of denouncing" for officers subservient to the cabinet: "the moral police of the army by his care had soon military agents in almost all the troops; it was so often these agents spied on and denounced each other”. According to historian Guy Thuillier, this practice of informing officers caused significant damage to the esprit de corps, as the officers jostled for position and personal advancement and would be one of the elements that would most scandalise public opinion, once the affair had been revealed.[41]

The situation within the French Navy

While the French Navy was not directly implicated in the Affair of the Cards, its leaders also undertook their own endeavors to carry out a "republicanization" of their officer corps. Indeed, the Navy, traditionally known as "the Royal", an ambivalent reference to the rue Royale — where the Navy staff sat, in the Hôtel de la Marine — and to its royalist sympathies, was closely watched by Republicans and criticized for its alleged particularism. They feared that its corps of officers, which cultivated its autonomy in relation to the political personnel in place, were still at end of the 19th century a danger to the regime.[43]

In fact, successive Ministers of the Navy — Édouard Lockroy (1896, 1898–1899), Jean-Marie de Lanessan (1899-1902) and Camille Pelletan (1902-1905) — endeavored to assimilate the Navy to the Republic. This enterprise reached its maximum intensity under Pelletan, who worked alongside General André in the Combes Cabinet. In fact, Pelletan "saw naval policy only through an ideological prism": he intended to promote the careers of petty officers and officers specializing in mechanics, because they were known for their republicanism; Likewise, his enthusiasm for the Jeune École was motivated as much by his strategic vision as by the desire to promote young officers committed to his cause. The new battleships which left the shipyards were named in homage to the French Revolution: Liberté, Danton, Démocratie and even Patrie. The period of the Radical Republic was also marked by a militant secularization of the Navy: in 1901, daily prayers, religious instruction and statutory Masses were abolished; in 1903, the tradition of the blessing of the Fleet was stopped; in 1904, the tradition of Lenten season fastings on Good Friday was lifted; finally, the fleet chaplain corps was dissolved in 1907. Pelletan's uncompromising anti-Catholic campaign often met with hostility from the Navy command, but also from Republican political leaders who reproached him for his excesses: thus, Paul Doumer, described him as genuine “national peril”.[43]

The Navy, even under Pelletan, did not go so far as to practice extensive registration of officers. The minister, consulted on the subject, replied that he "was not afraid that an admiral, however monarchist he was, would bring a squadron to Paris". Masonic lodges were nevertheless occasionally consulted on career advancements.[43]

Unveiling of the scandal

The intrigues of Humbert and Percin

Captain Charles Humbert was dismissed from André's office in July 1902. He was the source of the first leaks concerning the file system. Ordered to leave the Army following the Termes incident, he was appointed tax collector, first in Vincennes, then in Caen (the Minister of War having insisted on his removal from Paris). The dismissal of Humbert was commented on in the national press, which embarrassed André and his team, who feared that Humbert would seek revenge by publicly revealing the corrupt practices within the Cabinet, in regards to the filing system and Grand Orient surveillance network. This fear turned out to be well founded: eager for revenge, Humbert met with Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau — now withdrawn from politics but was a significant moral authority for republicans in the Third Republic — and inform him that André's cabinet gives too much credit to partisan informants when it came to advancements within the Army. General Alexandre Percin — former protector of Humbert — went even further on 20 September 1902, revealing to Waldeck-Rousseau the full extent of the Grand Orient involvement in the card system and the use of these cards by Captain Mollin. Concealing his own responsibility for the establishment and operation of the card system, Percin spontaneously offered his resignation to the former President of the Council. Waldeck-Rousseau refused it, but deeply indignant about the entire affair and fearing the backlash for republicans once it was revealed, he complained about what he had learned to Émile Combes on 30 September:[44]

Seen Combes. I reported the previous conversation to him. My opinion is that the procedure put in force at the War is inadmissible and will unleash legitimate anger when it is known. Combes agrees. All this must stop.

The card system was beginning to be more widely known among management personnel of the regime in general, outside the Ministry of War. As early as January 20, 1903, General Émile Oscar Dubois reported in his diary that the entire entourage of the President of the Republic, Émile Loubet, knew what was going on at the Ministry of War.[35]

Percin's was playing a double game: while he was managing the filing at the Ministry, he tried to put General André in difficulty by releasing the first leaks. Several hypotheses as to why he did this are possible: it is possible that he sought to provoke the fall of André in order to be able to personally replace him within the government — as the rumours accused him —, that he was working to put in place a successor whom he preferred — Eugène Étienne being the most appropriate candidate in this scenario — or that he sought to exonerate himself from the forthcoming card system scandal by throwing the responsibility on André and Mollin, knowing that it would eventually come to light.[35]

Multiplication of leaks

The second half of 1904 was to be marked by an upsurge in leaks about the carding system. In May 1904, a Masonic lodge in Bordeaux wrote a report on the subject of the displacement of a Captain of the local garrison — whom the Lodge had requested the removal —, a document which found its way into the hands of Laurent Prache, member of the Union libérale républicaine. On 17 June 1904, he challenged the government about the political influence of Freemasonry, opening hostilities in the Chamber of Deputies. He accused the Grand Orient of being "an occult agency for the surveillance of civil servants" and recalled an earlier scandal from 1894, where the Grand Orient acquired administrative services to "create information sheets on certain personalities". For Prache, officials, whoever they are, "suffer from this continual espionage"; he maintained that the semi-political character of the Grand Orient was in contravention of the 1881 law on freedom of the press and the association under the French law of 1901. But his attack was not supported by very convincing documents and Louis Lafferre, Grand Master of the Grand Orient and representative of the Radical Party, succeeded him on the platform to respond to these accusations; during the vote, on 1 July 1904, Prache's position was supported by 202 votes and opposed by 339 votes, which sided instead with the sitting Emile Combes government.[45]

In August 1904, Jean-Baptiste Bidegain, assistant to the Secretary-General of the Grand Orient Narcisse-Amédée Vadecard, sold to Father Gabriel de Bessonies a set of files that he copied during his work at the General Secretariat of the Grand Orient,[46] after revealing their existence to him at the beginning of 1904. Bidegain indeed “returned to the Catholic faith after mourning and personal disappointments”, which would have pushed him to change tack.[47] Father de Bessonies was the chaplain at Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, Paris and a staunch opponent of Freemasonry, was then in contact with the deputies Prache and Jean Guyot de Villeneuve.[48] However, he seems to have played only an intermediary role, the real instigator of the connection between Bidegain and the Parti nationaliste seeming to be Mgr Odelin, a member of the entourage of Cardinal François-Marie-Benjamin Richard.[49][50] A minority thesis — defended in particular by Pierre Chevallier — claims that Bidegain (godson of Mgr Odelin), was from the very start a Catholic sleeper agent of the Archdiocese of Paris, infiltrating the General Secretariat of the Grand Orient de France, to monitor the activities of the freemasons.[48]

In September 1904, the campaign against carding system resumed, this time in a series of articles in the newspaper Le Matin, which was known for its moderate republican outlook. The "denouncement in the Army" was itself denounced, Percin and Maurice Sarrail — a Freemason and former collaborator of General André — were severely criticised and the journalist Stéphane Lauzanne vigorously critiqued the actions of the Minister of War:[51]

It is not possible that you allow next to you, below you, outside you, to perpetrate this task of snitching and denouncing, which can be that of the police, but cannot be that of the French Army. There is no republicanism which can excuse a fault against honor and there is no masonry which can cover a spinning agency. The Republic does not need to live that thieving officers serve it, and Freemasonry does not need to continue to render services to the Republic that it is transformed into a denouncing office. All of this must come to an end.

The revelations of the newspaper provoked a new groundswell for pressing the government by the right — this time in the person of Lieutenant-Colonel Léonce Rousset. Some suspected that Captain Charles Humbert was a force behind the scenes pushing the series of articles in Le Matin. When Jean Jaurès (leader of the French Socialist Party) accused him of this, Humbert defended himself by publishing a letter in L'Humanité and took the opportunity to denounce on the one hand the practices of denunciation that he had undertaken to fight when he was still in the cabinet of André and on the other hand the treatment to which he was subjected in July 1902.[51]

The press also reported in September 1904 the words of General Peloux, in La Roche-sur-Yon. He presents the denunciation of "reactionary" soldiers as a duty to his officers: "If any of you showed any hostility to the government of today, I beg you to quarantine them and even I will give you a duty to denounce them to me ”. This declaration prompted the filing of a third interpellation with the government.[51]

Revelation in the Chamber of Deputies

In mid-September 1904, the nationalist deputy Jean Guyot de Villeneuve obtained from Captain Humbert documents that the latter had taken with him following his dismissal from the cabinet of the Ministry of War. Certain documents relating to the files undeniably bore the signature of General André. On 30 September 1904, Guyot de Villeneuve met Father de Bessonies and photographed a number of Bidegain's files in his possession. On 10 October, he returned to study the file in detail, accompanied by his friend Gabriel Syveton, treasurer of the Ligue de la patrie française. First they authenticated Captain Mollin's handwriting to ensure the files were genuine and then decided on a plan of action. On 15 October, the file containing the documents was secured within a safe at Crédit Lyonnais, while Guyot de Villeneuve decided to press forward with the revelation of the scandal, perhaps advised in this by Msgr Odelin. Indeed, both feared that the parliamentary debates on the Law of Separation of Churches and State would open quickly and were determined to prevent the Combes cabinet from achieving its ends.[46] Also, Guyot de Villeneuve unexpectedly filed a request for an interpellation, which was set for the session of 28 October, the same day as that scheduled for the interpellation of Rousset.[52]

The ruling government, despite the precautions taken, very quickly got wind of the maneuver because it subjected nationalist circles, including elected representatives, to extensive covert surveillance by the police.[52] Thus, the secretary of Syveton, who was a secret informant to the police, informed the Ministry of the Interior of Guyot de Villeneuve's plans. The only major measure taken was to move the files from the Ministry of War to Captain Mollin's home and to have the place guarded by the police.[46] A freemason policeman who worked at the Sûreté also warned the Grand Orient that "very important documents from the Grand Orient have fallen into the hands of the opposition". The news caused concern among the Army officers who belonged to Masonic lodges and thus had benefited most from the practices of the Ministry of War. They came to ask Vadecard for explanations. However, the government, confident of its majority in the House, did not seem to understand the extent of the threat, perhaps because the full extent of the betrayal of Humbert and Bidegain was not yet known. Thus, General André trumpeted during a banquet in mid-October: "We are now going to try to throw a division among those who are working against the republic Republic: we know the danger, we will not let ourselves be caught. The fight will take place this week, we will go frankly, squarely into the fight and if victory is lacking, it will not be our fault!."[52]

The details of the full blown scandal found its way into the press by late October. On the mornings of 27 and 28 October 1904, Le Figaro published detailed files on the affair of the cards, revealing in particular the existence of the "Carthage" and "Corinth" discriminatory carding system from the Army and implicating Captain Mollin directly. On 28 October, Le Matin also produced a feature on the index cards scandal.[53] On 28 October, Jean Guyot de Villeneuve challenged the government in the Chamber and revealed the ongoing relations between the Grand Orient and the office of the Minister of War.[54] At the rostrum, for nearly three hours,[55] he methodically read letters and files establishing that General André was relying on the information given by Freemasonry to decide on the advancement of officers. He ended his intervention by accusing the Grand Orient of being in reality the entity which directs the personnel of the French Army. The Minister of War denied the accusations and announced the opening of an investigation to assess the veracity of the claims alleged against his cabinet; if the facts were proven correct, he announced that he would resign. The vote following the interpellation gave the government only a 4-vote majority, showing the consternation of some members of the parliamentary majority.[54]

On 29 October, General André ordered the files of the Ministry of War to be destroyed. The only remaining files were therefore those taken by Bidegain and Humbert, and communicated to Guyot de Villeneuve.[56] The latter, to maintain the pressure on the government, released them in a trickle fashion to the national press - mainly Le Figaro,[57] L'Écho de Paris,[58] Le Gaulois and Le Matin[55] — and also to the provincial press for publication.[59] Also the day after the revelation in the Chamber, the Council of the Order of the Grand Orient published a manifesto in response to the accusations leveled against the obedience. It denounced the "traitor" Bidegain, "bribed by congregational money" and reported him to the vengeance of "all the masons in the world". Far from denying the registration carried out by itself, the Grand Orient affirmed in this manifesto to be proud of it: “We would like, in the name of all Freemasonry, to declare loudly that by providing the Ministry of War information on the servants loyal to the Republic and on those who, by their attitude always hostile, can raise the most legitimate concern, the Grand Orient of France has the claim, not only to have exercised a legitimate right, but to still have fulfilled the strictest of his duties”.[60]

Meeting of 4 November 1904

The parliamentary session of 4 November 1904 marked the climax of the affair of the cards.[8] Guyot de Villeneuve returned to the fray, providing material proof of General André's personal responsibility: producing a document initialed by him making explicit reference to the Grand Orient intelligence reports.[31] He then accused the Minister of War, directly, of having deliberately lied to the Chamber during the sitting of 28 October.[61] The deputy's revelations also showed that Émile Combes (the leader of the government) and Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau (the darling of the republicans) were also aware of the card system.[62] Nevertheless, Guyot de Villeneuve did not manage to bring down the government; between 28 October and 4 November, the Radicals and the Socialists beat the recall of the deputies supporting the Ministry of War to keep the government in the majority, with as a line of defense which recognised that the registration system existed but claimed that it was justified as a bulwark against "anti-government reactionaries" within the Army.[54] A vote on the agenda took place and showed that the government's credibility was eroding; their majority had reduced to a slim margin of only 2 votes. Among the votes of the majority were those of six deputy ministers.[63] The royalist Armand Léon de Baudry d'Asson had tried to ban their participation in the ballot at the start of the sitting, during the examination of urgent resolutions.

General André defended himself vehemently: “I know that a number of my enemies have sworn to have my skin. I will resist all these attacks, gentlemen, and I will remain at my post until a clear vote in the Chamber has excluded me from it." It was then that the nationalist deputy Gabriel Syveton, — who had already distinguished himself in the hemicycle in 1903 by a lively altercation with the Minister of Justice Ernest Vallé —, advanced towards the ministers' bench and, two times, vigorously slapped the Minister of War. This gesture triggered a generalized uproar in which parliamentarians from the right and left came to blows while Henri Brisson hastily suspended the meeting.[8]

Abandoned by dozens of moderate Republicans, the Combes government was saved at the last minute by this sitting incident. Indeed, the slap of Syveton reshuffled the cards: the delegation of the left - the governing body of the coalition of the Bloc des gauches — proposed an agenda that temporarily resolved the Republican majority, gathering 297 votes for and 221 against, with about sixty abstentions, i.e. a majority of 20 votes.[63] Having shown that the support of the cabinet was played out by only two votes, the session of 4 November opened with a ministerial crisis with high stakes: with the possible Law of Separation and the control of the legislative elections of 1906 to play for.[63]

Troubles in the provinces

The revelation of the card system shook traditional France in the provinces and stirred up popular sentiment against the "cardists": important incidents and quarrels occurred in nearly forty departments, as people who were personally attacked in the reports were outraged, seeking regress and those who were offended for religious reasons at the attempt to exclude French Catholics from participation in their national Army.[64]

Suspicion was heightened in the garrisons, and informers were sought from reports of debates in the House and revelations in the newspapers. Withering the “casseroles” became, in the corps of officers, a question of honor. Officers who had files created on them as part of the scandal, challenged those who created reports on them to a duel, as in Nancy where a Commander confronted the Worshipful Master of the local Masonic Lodge. In La Roche-sur-Yon, in January 1905, Lieutenant-Colonel Visdeloup de Bonamour sued Stéphane Guillemé, mayor of the town, Worshipful Master of the Masonic Lodge and author of numerous files on individuals within his regiment.[65] In Marseille, the Freemason lawyer Armand Bédarride was publicly scolded and in Lyon, where Professor Joseph Crescent, the same occurred as he faced significant public backlash.[66] Directly implicated in the Chamber of Deputies by Guyot de Villeneuve as a compiler of "cards", Joseph Talvas — mayor of Lorient and Worshipful Master of the Nature et philanthropie (Nature et philanthropie lodge) — committed suicide on 5 November 1904.[67]

In Poitiers, the prefect Gaston Joliet was "swept away by the scandal and thrown as food for the press".[68] Indeed, Guyot de Villeneuve mentioned his name first on the platform on 28 October and then on 1 November, several denunciation notes, written by Joliet on prefectural letterhead and sent to the Grand Orient de Francee, were published by L'Écho de Paris.[58] Joliet's file on Commander Henri Marie Alfred de Cadoudal, of the French 125th Infantry Regiment, triggered consternation in the department. The file on de Cadoudal described him as a “Royalist, fanatic clerical, former student of the Jesuits; continues to have ongoing relations with them. Intelligent, skillful and of a deceit that goes beyond anything that one can imagine. This officer is the most dangerous in the Poitiers garrison. He hates all that is republican and anticlerical and does not hide it. He is an officer to be sent to Africa or to the colonies as soon as possible; he is of the Chouan-type and very dangerous in a country which was part of the old Vendée”. On 3 November, the Colonel of the 125th Infantry Regiment had to use all his authority so that the officers of his regiment did not attack the prefect on his arrival at Poitiers station. Irreverent inscriptions flourish in the streets of the city referencing the perfect. On 5 December, in Paris, in front of the Théâtre du Vaudeville, Joliet was recognized and slapped by the political journalist André Gaucher.[69] At the trial of Gaucher, 5 January 1905, Commander Charles Costa de Beauregard recognised Commander Nicolas Pasquier — organizer of a network of denouncements — whom he verbally inveighed against; police officers were obliged to intervene to prevent a brawl at the end of the hearing. On 4 March, Joliet — who did not set foot in Poitiers — was finally dismissed by the Rouvier government and appointed governor of Mayotte, ironically, in the colonies off the coast of Africa.[70]

On 23 December 1904, in front of the Université de Lille. Faculté de médecine, Captain Avon slapped and hit with his cane Dr. [Charles Debierre — Worshipful Master of the Lodge La Lumière du Nord —, whom he accused of having drawn up files on him and his father, the retired General Avon.[71] Following this assault in the middle of the street, Captain Avon was arrested and was sentenced on appeal, on 3 February 1905, to one hundred francs in damages and the same sum of suspended fine, the Court of Appeal of Douai's having considered as a mitigating circumstance "that it was common knowledge that Debierre had sent information on the officers of the Lille garrison". Nevertheless, the radical newspaper Le Réveil du Nord having published the Avon files had asked Debierre to intervene in favor of his career as well as that of his father, the moderate conservative circles did not take sides with the two soldiers, whose conduct they did not approve of. As for the nationalists, they ceased their offensive in Nord as soon as the first revelations about Syveton's death were revealed, which plunged them into a certain disarray.[72]

Ministerial crisis

First oppositions (June 1902 — October 1904)

Since 1902, the President of the Republic Émile Loubet had strong disagreements with the policies of President of the council, Émile Combes. He disapproved of the "anticlerical and sectarian" policy of the Combes cabinet, protested against the dismissal of Captain Humbert and regularly discussed with the Secretary General of the Elysee Abel Combarieu the nepotism instituted by Combes: "Anyone can ask, demand anything they desire, evaluating themselves at such a rate and always finding parliamentary influences to obtain it ”. On 20 March 1903, Paul Doumer — although he himself was a Freemason — met Loubet to express his concerns about the dominating influence of the Masonic lodges on the government. Supported by a few other Republican politicians — including Théophile Delcassé — Loubet nonetheless remained in the minority and was powerless to moderate or dismiss Combes.[73] He considered resigning for a period, but the prospect of his replacement by an associate of Combes held him back. In July 1904, Loubet's opposition to the Law of Separation of Churches and State also became public, helping to weaken majority support for the government.[9]

In September 1904, the internal stability of Combes' regime deteriorated a little more. In fact, during his speech in Auxerre on 4 September, he pronounced a sentence that would trigger a controversy: "Our political system consists in the subordination of all bodies and all institutions, whatever they may be, to the supremacy of the republican and secular state”. A lively press campaign was launched: on 7 September, Le Temps accused him of defending the “tyrant state”; In Le Matin, Georges Leygues spoke for parliamentarians tired of Combes' authoritarianism: “M. Combes has no friends, he only has servants. Our parliamentarianism, which was formerly a system of free discussion, has become under his reign a disciplinary system where everyone must think about order and follow the instructions. It was not worth driving out the monks to reestablish a new congregation in the midst of Parliament, out of which there is no salvation!"; finally, the Revue des Deux Mondes published on 15 October an anonymous pamphlet entitled Le Ministère perpetuel, authored by the deputy Charles Benoist, member of the Republican Federation:[74]

[The government] punishes and rewards citizens and boroughs, depending on whether they voted "well" or "badly". Are they voting "well"? Any favour is granted. "Wrong"? No justice. The West and North-West of France, which refuse to join the Bloc, are in quarantine. Their ports are left silted up, and they will only have railways for what they had before or what they pay for. State subsidies will be for the moving red Midi. The same for individuals; if they vote "badly", they will be spied on, denounced, prosecuted and attacked until the fourth generation.

During the turmoil of the cards (October 1904 — December 1904)

Between 18 October 1904 and 15 January 1905, the Combes government attempted to reform its parliamentary majority, the Bloc des gauches, while the cards affair experienced new developments at the national level.

Resignation of André and the Mollin affair

On 6 November 1904, two days after the stormy session in which General André was slapped, Combes confided to Loubet that he was considering dismissing the Minister of War, whose credit was damaged beyond repair. Eager to provoke the fall of the entire cabinet and not the only resignation of the minister, Loubet argues that it is impossible to separate the government from André in view of the insult he had received and that this would prove the Groupe républicain nationaliste right. At the same time, Loubet began to plan for the next government, which he intends to entrust to Delcassé.[54] André resisted a few days with the support of Combes. Finally, hoping to save his government, Combes forced André to resign on 15 November, without compensation — he was, in the words of Georges Clemenceau, “Turkish strangled”,[75] and replaced with Maurice Berteaux, a rising star of the Radical Party, a Freemason and also on good terms with President Loubet.

On 17 November 1904, to save the face of the government, Combes tried to blame Captain Henri Mollin for the excesses of the file system, whom General André had forced to resign on 27 October and he declared to the Chamber: "Because an officer of ordinance has devised a detestable intelligence system, should the blame be placed on those he has unwittingly deceived?". Indignant by this disavowal and attempt to make him the scapegoat for the affair, Captain Mollin withdrew his resignation — which had not yet been published in the Journal officiel de la République française — and sent a letter to Berteaux asking to appear before a board of inquiry. There was a panic in the Ministry of War: Berteaux, in order not to upset the left, refused to initiate proceedings against Mollin, because it would then be necessary to investigate all the officers suspected of involvement, starting with Commander Pasquier. Consequently, he refused to report the resignation of Mollin.[76]

On 5 January 1905, General André, in a letter, tried again to make Mollin a scapegoat, explaining: "I was wrong to report absolutely to this officer for the correspondence to be exchanged [with the Grand Orient] and not to require him to submit all his letters to me first”. He also affirmed that he was not informed that denouncing was practiced between officers, a practice which he said he disapproves of.[76]

Defence of the "cardists"

Relying on the support of the socialist left, Émile Combes refused to sacrifice the network of informers. But the Minister of Public Education Joseph Chaumié, feeling the turning tide and wishing to place himself in a future government, broke with this by reprimanding Gaumant, a teacher from the high school of Gap who denounced officers while trying to concealing his handwriting; the latter was exiled to the lycée in Tournon-sur-Rhône. The Keeper of the Seals followed his example and demanded the resignation of Charles Bernardin, justice of the peace in Pont-à-Mousson and member of the Council of the Grand Orient de France. This move was too much for the Grand Orient: Adrien Meslier, Fernand Rabier, Alfred Massé and Frédéric Desmons, Masonic parliamentarians who were all members of the Council of the Grand Orient de France, intervened with Combes directly.[77]

On 17 November 1904, Combes reaffirmed his position by affirming in the Chamber: “[I do not want] to deliver republican officials to vengeance who [have] been denounced by certain papers whose authenticity cannot even be guaranteed. We do not want to lose the propaganda work of five years in one week!". By authority, he forced Vallé to reconsider the sanctions he had pronounced against the informing magistrates, Bernardin and Bourgeuil — former public prosecutor in Orléans —, and urged his ministers to refuse any concession to the right by moving against informers.[77]

At the same time as these pressures on the government, the Grand Orient resumed the offensive: on 23 November, Grand Master Louis Lafferre gave an interview to the newspaper Le Matin in which he affirmed that the obedience as a whole was not informed of the registration and called for a purification directed against the right: "It remains to be seen whether democracy, some day tired of being badly served or betrayed, will not seek to see clearly in its affairs and will not take the broom of the great days, without worrying about the hierarchical path or the virtue of parliamentarians, but only the purification of civil servants, which has been promised to him for thirty years, and which we claim to do without his assistance”.[78]

The "delegates" of Combes

To defend his cabinet, Combes tried to regain control by affirming on 17 November that the government is entitled to obtain information from delegates across the country. Derided by the nationalist Albert Gauthier de Clagny — who quipped “Which delegates? Delegated by whom and for what task? If these are people who must make inquiries in all the municipalities, in good French they are called snitches"—, the President of the Council retorted: "It is the notable of the municipality who is invested with the confidence of the Republicans and who, as such, represents them to the government when the mayor is a reactionary”. On 18 November, he formalized the system by means of a circular addressed to the prefects:[79]

One of the essential duties of your office is to exercise political action on all public services and to faithfully inform the government about civil servants of all orders and candidates for public office. It is not for me to limit the field of your information, but I am permitted to invite you to draw your information only from officials of the political order, republican political figures invested with an elective mandate and those you have chosen as delegates or administrative correspondents because of their moral authority and their attachment to the Republic.

On 22 November, he clarified to his ministers that "so that the political action of the prefects can lead to useful results, it is essential that these senior officials be called upon to express, from a political point of view, their opinion on all the proposals of interest to the staff of the various administrations, in particular with regard to questions of appointment and promotion”. Georges Grosjean, followed by several other parliamentarians, immediately filed a request for an interpellation on the subject of "the official organization of the denunciation revealed by the ministerial circular of 18 November", set for 8 December.[80]

On 1 December, Louis Lafferre, whom Combes chose to reassure the Bloc militants, gave a speech at the rostrum to justify the Masonic political surveillance of the French Army. Lafferre's thesis was that the government has the right to inquire about reactionary officials; he accused the right of maintaining an atmosphere of civil war in the country.[81] Interrupted several times, he finally exploded:[80] "We now know from the reactionary newspapers the presumed state of the Army, which has 90% enemies of the Republic if this information is correct. I ask the Minister of War if it is advisable to let this country be guarded by a coup d'etat!", this triggered a prolonged uproar in the hemicycle.[81]

On 9 December, the day after a vote in the Senate in which the government obtained only two majority votes, the prefects of Combes were recalled from their departments to "warm up with promises the zeal of hesitant deputies or where appropriate to try to intimidate them."[82] Jean Jaurès, leader of the Socialists, put his political and moral authority at the service of Combes, as he was also convinced of the need for political control of the Army and fearing that the fall of Combes would definitively disrupt the Bloc des gauches.[83] They were attacked by Alexandre Ribot who said "You have lowered everything that was great, generous in this country, that is your crime!" and also Alexandre Millerand who said "Never a Minister of the Empire, under the lethargic sleep of our freedoms, would have dared to stoop to these abject practices!", the President of the Council managed to gather 296 votes in his favour (and 285 against) by affirming that the Republic was threatened by the maneuver of the right, offering himself a welcome respite.[84]

Death of Gabriel Syveton and Ms. Loubet's file

Following the incident of 4 November, Gabriel Syveton was prosecuted for his physical attack on the Minister of War; his friends, eager to make his trial a platform against the government, voted with the majority of deputies in favor of lifting his parliamentary immunity.[85]

On 8 December 1904, the day before his trial before the Seine Assize Court, the nationalist deputy was found dead — asphyxiated —, his head was found resting in his fireplace, covered with a newspaper, with the gas pipe from the radiator in his mouth. The nationalists, François Coppée and André Baron in the lead, denounced this as a Masonic assassination. However, the investigation concluded that it was suicide, and Jules Lemaître admitted before the examining magistrate that Syveton had taken 98,000 francs from the Ligue de la patrie française of which he was the treasurer, money which was subsequently returned by his widow. It seemed that Syveton committed suicide after being threatened with revealing his embezzlement and the possible affair he had with his daughter-in-law, the thesis of the investigators was joined by the nationalists Léon Daudet, Louis Dausset, Boni de Castellane and Maurice Barrès, who accused the government of being behind the moral pressure exerted on Syveton which caused him to commit suicide.

On 21 December, another twist emerged: Le Temps reveals that the entourage of the President of the Republic was listed by Commander Pasquier: in the file concerning Commander Bouillane de Lacoste, Loubet's ordering officer, it was written: "The clerics are all-powerful in Montélimar. Bourgeois, industrialists, civil servants, magistrates, officers, are clericals. However, this clerical world has always supported Mr. Loubet, because of his tolerance. It is therefore in this world, by connections, by the family relations of Mrs. Loubet, who are very clerical, that the President took two orderly officers”. The publication of this card put the government in a very embarrassing position. On 23 December, Adrien Lannes de Montebello read this intelligence report out in the Chamber and exclaims: “The Chamber will not be in solidarity with the denunciation. She has a duty to stop the espionage at the door of the Head of State!"; Minister Berteaux, very embarrassed, explained that Pasquier swore never to have written this card, an explanation rejected by Paul Deschanel[83] of the Democratic Republican Alliance, who added: “They claim that republican officers must be covered. What is the Republic doing in this? I doubt that the men who engage in such practices have a drop of Republican blood in their veins."[86]

Fall of the Combes cabinet

Jean Guyot de Villeneuve was at the origin of the final maneuver which brought down the Combes government. Since Combes formally refuses to punish informers, the nationalist deputy shifted the debate to the field of the national order of the Legion of Honor: on 9 December, he protested against the officers who denounced their comrades, some of whom "carry the sign of honor: will they be allowed to wear it?". Individual complaints had already been addressed to the Grand Chancellor of the Legion of Honor, General Georges-Auguste Florentin, but Combes had endeavored to cover the first legionaries incriminated, including Paul Ligneul, mayor of Le Mans.[86]

A petition is circulating in Paris, coordinated by General Victor Février, former Grand Chancellor of the Order. On 28 December 1904, the request was addressed to General Florentin:[87] “The undersigned ask you, Mr. Grand Chancellor, to bring the matter before the Council of the Order and to make public the solution(s) that will take place for all the legionaries incriminated or who could still be. France and the whole world need to know that there are in the Legion of Honor neither defamers, nor slanderers, nor liars, and that, if, unfortunately, there were some, there are no more now.";[88] a complaint was filed for misconduct against honor.[87] The 3,000 signatories, all holders of the Legion of Honor, had in their ranks many "good republicans", influential figures such as Émile Boutmy, but also a large number of soldiers. In fact, it was a dangerous document for the Combes government.[88]

At the same time, the government was maneuvering behind the scenes to circumvent General Florentin. On 16 December, Combes sent the Keeper of the Seals, Ernest Vallé to the Grand Chancellor to ensure that the complaints were filed away without further action. Florentin resisted, however, retorting "that it was not up to him, the Grand Chancellor, to dismiss of his own accord the complaints formulated by members of the order, when they aimed at serious faults against honor; that denunciation was one of these facts; that he had, consequently, regularly seized the council of the order of the complaints which had reached him, and that the procedures would be continued." He specified that complaints concerning soldiers would only be investigated after the decision of a military disciplinary council — according to the regulations —, those concerning civil servants would only be examined after the opinion of the Minister — in accordance with case law —, but that all the others would be referred to the Council of the Order. The next day, Combes summoned Florentin and threatened to dismiss him, but the General did not allow himself to be intimidated and obtained the support of Loubet. Spurred on by the hierarchs of the Grand Orient, Combes refuses to allow the slightest informer to be condemned. Also, he came into conflict with the President of the Republic. On 5 January 1905, the revelation of government pressure on Florentin by Le Temps — the leak came from Loubet's entourage — put Combes in a position of embarrassment.[88]

On 9 January, the Council of the Order of the Legion of Honor summons Begnicourt, a retired commander, to respond to cards of which he was the author. On 12 January, the Council unanimously decided to strike Begnicourt from the executives of the Legion, a decision known in Paris the next day. The government was "forced into an inextricable situation, it which had undertaken to take no action against any informer whatsoever".[89]

The mandate of the President of the Chamber, Henri Brisson was coming to an end, Paul Doumer put forward his candidacy on 10 January 1905. The latter immediately specified that this approach was directed against the Combes cabinet and "the corrupt practices of which it uses" and not against Brisson personally. The poll was held on 12 January; the vote being done by secret ballot, the pressures which the presidency of the Council usually used were ineffective and moderate republicans took advantage of this to precipitate the fall of Combes: Doumer wa elected against Brisson with a majority of 25 votes. There was a strong reaction on the left: Doumer was qualified as a “traitor”[89] and was subsequently excluded from the Grand Orient de France.[90]

The election of Doumer proved that Combes had lost control of the House. The latter made his final emotional plea on 13 January, prophesying a lasting crisis if he is forced to leave power: “It is not a crisis of ministry, but a crisis of majority which would open tomorrow. I have before me a coalition of impatient hatred and hatred, hatred attracts ambitions”. On 14 January, when the progressive Republican Camille Krantz asked him if he will allow Begnicourt to be condemned, Combes deferred to the President of the Republic: "It is up to him alone to make his intentions known". The agitation of the Chamber wa at its height; Alexandre Ribot thundered: “There is a responsible ministry, I imagine! You have just discovered the President of the Republic!", Combes and Vallé got entangled in their explanations.[91]

On 15 January, the day after this stormy meeting, Émile Combes announced to Loubet the resignation of his government, a resignation that he officially submitted to the Council of Ministers on 18 January, Loubet having had to be absent due to the death of his mother.[91]

Formation of the Rouvier cabinet

President Loubet, to choose a successor to Combes, came under significant pressure from the Bloc des gauches. The latter indeed wanted "a Combes ministry without Combes", without any radical dissident or a former minister who served under Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau. However, many Republicans wanted to be more pragmatic and distance themselves from the scandal. Thus, the former vice-president of the Senate Pierre Magnin declared to Armand Fallières: “Tell the President that the first thing to do is to settle the affair of the files; we republicans have had enough of being called spies or friends of spies; the program of the new cabinet does not matter; at this point in the legislature, it is secondary, we will vote on the bills as we wish; but let this dirty business be liquidated as soon as possible; the man who is most capable of doing it is Rouvier ”. Despite his marked personal preference for Delcassé, Loubet gave in and on 21 January 1905 appointed Maurice Rouvier as President of the council.[92]

Rouvier's policy of appeasement

Rouvier formed a government from which members of parliament who had spoken out against Combes, even if only once, were excluded. However, he did not continue the previous Cabinet's unconditional defense of informers from the affair. Under his leadership, and although Henry Bérenger threatened in L'Action quotidienne reprisals from the radicals — "will find in our ranks more than one Fernand de Christiani!" —, the Minister of Justice signed on 27 January a decree striking out from the executives of the Legion of Honor, the commander Begnicourt. On the same day, the Council of Ministers laid off General Paul Peigné — commander of the 9th Army Corps, sitting on the Superior War Council[93] and a freemason belonging to the Grand Lodge of France[94] — who was personally implicated in the scandal (he had boasted in a letter to Narcisse-Amédée Vadecard, that he had managed to exile a commander and four captains to undesirable posts on the eastern border). However, to appease the left, Generals de Nonancourt and Denis Henri Alfred d'Amboix de Larbont — who publicly expressed their outrage when the scandal had been revealed — were also dismissed.[93]

On 27 January, during his ministerial declaration, Rouvier promised an end to the interference by Freemasonry in government bodies, but condemned "the violent formal notices formulated by the opponents of the Republic [...] without worrying about whether, to ensure their triumph, they do not risk compromising national defense and dividing France herself”; the symbolic actions taken against Begnicourt and Peigné were presented as sufficient and Rouvier refused to hit "the republican officials who, in good faith, may have been mistaken". He obtained a majority of 373 votes, with 99 against, his support being equally divided between on the one hand radical-socialists, radicals and republicans, members of the Bloc, and on the other hand, conservatives, progressive republicans and dissident radicals, originating from the common opposition to Combes.[93]

Rouvier also managed to get Jean Guyot de Villeneuve to stop publishing further files; the nationalist deputy agreed to comply in exchange for promises of the government to abandon political discrimination in the Army and reparations for officers who were hampered in their career advancement due to the political-religious discrimination of the affair of the cards. To do this, Guyot de Villeneuve tabled a bill to set up a military commission in order to obtain career upgrades for the officers targeted by the denunciation, but the Minister of War refused, promising only to examine individual cases.[95]

On 11 July 1905, the President of the Council continued his policy of appeasement by presenting to the Senate a bill of amnesty concerning offenses and contraventions in matters of elections, strikes, meetings, the press, convictions in the Sénat (Troisième République)(which concerned the Conspiracy trial before the Haute Cour (1899)) and finally — this is the main thing — of libels.[85] The discussion in the House was heated and some parliamentarians point out that this amalgamation is problematic from a legal point of view because on the one hand, the acts of denunciation incur disciplinary and non-legal sanctions and, on the other hand, the stain against a person's personal reputation cannot be whitewashed by law. However, the law was passed on 30 October 1905.[95]

Mollin's revelations

Despite the appeasement efforts of the Rouvier government and the hope of republicans that public attention on the affair could now be put to rest, the cards affair experienced some twists and turns during 1905, with some old scores still to settle.

The first of these was the publication by Captain Henri Mollin of a series of articles in Le Journal, in February 1905, in response to André's letter of 5 January. These articles were brought together by Mollin — assisted in his task by the journalist Jacques Dhur — and published as a book called The Truth on the Affair of the Cards, published in March. Mollin made a certain number of new revelations — with sufficient precautions to avoid being attacked in court — and these later relaunched the scandal.[96] He began by accusing Charles Humbert with covert words of having stolen documents from André's cabinet and of having handed them over to Jean Guyot de Villeneuve (which was later proven to have occurred). He also accused General André of having consulted "the summary of more than three thousand files from both the Grand Orient of France [and] the prefectures", while the latter claimed not to have had more than forty files in front of him. Mollin recalled the interview André had with Frédéric Desmons (Grand Master of the Grand Orient) on the establishment of the card system; finally, he blamed Lemerle who assisted him in the filing service and was himself not penalized for this. He then attacked General Alexandre Percin, whom he accused of being the real man in charge of the file system, of having intrigued against the minister and finally of having, leaving the cabinet in March 1904, copied the political files of the 300 officers of the division he was to take command of.[97]

Finally, Mollin revealed that Jean-Baptiste Bidegain had redacted certain documents by recopying them, in particular by removing the favorable mentions present on the files of certain officers presented as conservatives. Thus, Henri Le Gros, then lieutenant-colonel of the French 3rd Infantry Regiment, was described "reactionary and convinced Catholic" on the file of Bidegain, while he is presented as "reactionary and convinced Catholic, but very benevolent for his men who esteem him a lot” in the equivalent Grand Orient file. It therefore seems that a certain number of files published in the press are therefore "rigged and truncated", in Mollin's words. Due to the destruction of cabinet files by General André, it is nevertheless impossible to estimate precisely the proportion of files redacted in this way.[57]

The Percin affair

Up until this point the nationalists had spared Percin from their attacks, instead focusing on others.[57] The historian François Vindé has advanced the hypothesis that “the files stolen from the Ministry of War had been delivered by Humbert and his friends with the promise that Percin would be spared”.[98] Regardless, whether or not this arrangement had once existed, Mollin's questioning of Percin agitated nationalist circles, which now insisted on Percin's dismissal from Army.[57] Even the deputies of the Bloc des gauches were "unanimous in recognizing how reprehensible the conduct of General Percin was".[96] Also, the right-wing Bonapartist senator Louis Le Provost de Launay called on the government on 30 March 1905 in the following terms:[99]